Jean-Baptiste Huet, often referred to as Jean-Baptiste Huet I to distinguish him from family members, stands as a significant figure in late 18th and early 19th-century French art. Born in Paris in 1745 and passing away in the same city in 1811, Huet navigated a period of profound artistic and political change, leaving behind a rich legacy as a painter, engraver, and designer. He is particularly celebrated for his charming pastoral scenes and his sensitive, skillful depictions of animals, genres in which he excelled and gained considerable recognition during his lifetime. His multifaceted career also encompassed important contributions to the decorative arts, most notably through his designs for printed textiles.

Artistic Lineage and Early Training

Jean-Baptiste Huet was born into an environment steeped in artistic practice. His father, Nicolas Huet the Elder, was a painter associated with the Garde-Meuble de la Couronne (the royal furniture repository), specializing in animal subjects. His uncle, Christophe Huet, was also a painter, known for his decorative singeries (scenes involving monkeys in human attire) and arabesques. This familial background undoubtedly provided young Jean-Baptiste with early exposure to artistic techniques and the professional world of artists in Paris. His formal training began around 1764 under Charles Dagomer, a minor painter but likely a competent instructor in foundational skills.

Huet's development was further shaped by his association with Jean-Baptiste Le Prince, a painter and etcher known for his Russian genre scenes and his innovative work with aquatint. Le Prince, himself a student of the great François Boucher, likely imparted aspects of Boucher's style and thematic interests to Huet, particularly the taste for pastoral subjects and a certain Rococo sensibility, albeit adapted through Le Prince's own artistic personality. This combination of familial immersion and formal tutelage prepared Huet for his entry into the official art establishment of the Ancien Régime.

Acceptance into the Académie and Early Success

A pivotal moment in Huet's career arrived in 1769 when he was accepted (agréé) into the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture as a painter of animals. This official recognition was granted upon the presentation of his reception piece, the dynamic painting Dog Attacking Geese (Un dogue se jetant sur des oies). Now housed in the Louvre Museum, this work demonstrated his ability to capture animal movement and drama with convincing naturalism and energy, fulfilling the requirements for his chosen specialization within the academic hierarchy.

His acceptance into the Académie allowed him to exhibit regularly at the official Paris Salon, the most important venue for artists to display their work and gain patronage. He debuted at the Salon of 1769, and his works were generally well-received by critics and the public. He continued to exhibit throughout the 1770s and 1780s, solidifying his reputation primarily as an animalier and a painter of gentle, idyllic pastoral scenes often featuring shepherds, shepherdesses, and their flocks, rendered with a soft touch and appealing sentiment.

The Influence of Boucher and the Rococo Legacy

Jean-Baptiste Huet's art is inextricably linked to the prevailing Rococo style, particularly as embodied by François Boucher. While Huet developed his own distinct manner, the influence of Boucher is evident in his choice of pastoral themes, his often light and delicate color palette, and the overall charm and decorative quality of many of his compositions. Boucher had popularized idealized visions of country life, populated by elegant shepherds and shepherdesses in picturesque, albeit unrealistic, settings. Huet adopted these themes but often infused them with a greater degree of naturalism, especially in his depiction of animals.

Compared to the sometimes overtly sensual or mythological works of Boucher or the exuberant fêtes galantes of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Huet's pastoral scenes tend towards a gentler, more sentimental mood. His shepherds and shepherdesses appear less like disguised aristocrats and more like idealized, yet somewhat more grounded, country folk. However, the Rococo emphasis on grace, elegance, and pleasing compositions remained a constant thread in his work from this period, ensuring its appeal to patrons who favored decorative and lighthearted subjects.

Mastery of Animal Painting

While adept at pastoral landscapes, Huet's primary recognition by the Académie and arguably his greatest strength lay in the depiction of animals. He stands as one of the most accomplished animaliers of the pre-Revolutionary period in France, continuing a tradition notably represented earlier in the century by Jean-Baptiste Oudry. Unlike Oudry, whose work often focused on the drama of the hunt or royal menageries, Huet frequently depicted domestic animals – sheep, cattle, dogs, goats – within peaceful, rural settings.

His studies of animals reveal a keen eye for observation and anatomical accuracy. He rendered the textures of wool, fur, and feathers with convincing detail, capturing the characteristic postures and movements of different species. His drawings, often executed in chalks or ink wash, showcase his facility in capturing the essence of his animal subjects quickly and effectively. These studies often served as preparatory work for larger paintings or designs, demonstrating his commitment to understanding his subjects thoroughly. Works like The Farm (La ferme) exemplify his ability to integrate animals naturally into broader pastoral compositions.

Pastoral Ideals and Dutch Echoes

Huet's pastoral landscapes tap into a long tradition in European art, idealizing rural life as a peaceful escape from the complexities of the city. While influenced by the French Rococo tradition, his work also shows an affinity with 17th-century Dutch Italianate painters. Artists like Nicolaes Berchem, Paulus Potter, and Aelbert Cuyp had excelled in depicting sunlit landscapes populated with cattle, sheep, and shepherds, often imbued with a tranquil, golden light. Huet seems to have absorbed lessons from these Dutch masters, particularly in his handling of light and atmosphere and his focus on the realistic portrayal of livestock within believable landscape settings.

His scenes often feature motifs common to the pastoral genre: shepherds resting under trees, flocks grazing peacefully near streams, rustic cottages, and ancient ruins hinting at an Arcadian past. These compositions evoked a sense of nostalgia and tranquility that resonated with contemporary tastes, offering an idealized counterpoint to the realities of agricultural labor. Huet skillfully balanced decorative appeal with convincing details of rural life and animal behavior.

Innovations in Printmaking and Drawing

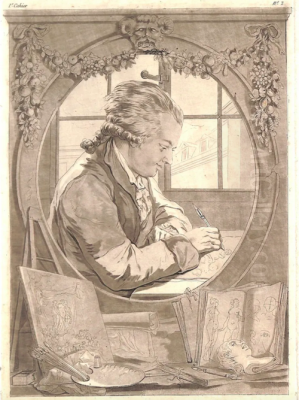

Beyond his paintings, Jean-Baptiste Huet was a prolific and skilled draftsman and printmaker. He produced numerous etchings and engravings, often reproducing his own designs or creating independent compositions. His drawings, frequently executed in red chalk (sanguine) or black chalk heightened with white, were highly sought after and admired for their fluency and charm. Many of these drawings were translated into prints, making his compositions accessible to a wider audience.

He notably collaborated with the engraver Gilles Demarteau, who specialized in the "crayon manner" (manière de crayon) technique. This intaglio printing method skillfully imitated the appearance of chalk drawings, complete with the texture of the paper. Demarteau engraved many of Huet's drawings, particularly pastoral scenes and studies of animals and children, capturing the softness and spontaneity of the originals. Huet also embraced stipple engraving, a technique using dots rather than lines to create tone, which became popular in France partly through the influence of engravers like Francesco Bartolozzi in England. His print Monkey with Bananas (L’Orang-outan. Le Coaita), possibly utilizing color printing techniques related to the crayon manner, showcases his engagement with graphic arts.

Designing for Industry: The Toiles de Jouy

Perhaps one of Huet's most enduring legacies lies in his work as a designer for the burgeoning textile industry. He became one of the principal designers for the famous Oberkampf manufactory at Jouy-en-Josas, near Versailles. Founded by Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf, this factory specialized in producing copperplate-printed cotton fabrics, known as toiles de Jouy. These textiles, featuring intricate monochrome designs typically printed in red, blue, or sepia on a white or cream background, were immensely popular for clothing and interior decoration.

Huet supplied numerous designs for Oberkampf between roughly 1783 and his death in 1811. His designs often featured his signature pastoral and animal motifs, arranged in complex, repeating patterns. He adapted his style perfectly to the medium, creating vignettes of country life, allegorical scenes, and depictions of animals and plants that were both decorative and informative. One famous example is The Labors of the Manufactory (Les travaux de la manufacture), which uniquely depicted the various stages of textile production at the Oberkampf factory itself, celebrating industry within an artistic framework. He also designed patterns incorporating exotic themes, such as Egyptian motifs following Napoleon's campaigns, seen in Les Monuments d'Égypte. His work significantly shaped the aesthetic of toile de Jouy and demonstrated his versatility in applying his artistic skills to industrial production. He also provided designs for the prestigious Gobelins and Beauvais tapestry workshops.

Scientific Observation and Illustration

Huet's interest in the natural world extended beyond purely artistic representation. His detailed studies of animals and plants reflect the spirit of scientific inquiry characteristic of the Enlightenment. This is further evidenced by his commission to create a large number of illustrations – reportedly over 240 – for the Muséum d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris. While specific publications featuring these illustrations require further research to pinpoint definitively, this work placed him in the company of artists contributing to the great scientific publications of the era, aimed at cataloging and understanding the natural world.

His designs, even those for decorative purposes like the toiles de Jouy, often included meticulously observed botanical elements, insects, and diverse animal species. This attention to detail suggests a genuine fascination with natural history, aligning his artistic practice with the era's emphasis on observation, classification, and the dissemination of knowledge. His ability to combine scientific accuracy with aesthetic grace was a hallmark of his talent.

Navigating the Revolutionary Era

The French Revolution, beginning in 1789, brought profound changes to French society and its artistic landscape. The Académie Royale was suppressed in 1793, and artistic patronage shifted. Neoclassicism, championed by artists like Jacques-Louis David, with its emphasis on historical subjects, moral virtue, and civic duty, became the dominant style. While Huet's Rococo-inflected pastoral and animal scenes might seem at odds with the stern tenor of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods, he successfully continued his career.

He adapted to the changing times, continuing to exhibit at the Salons (which became more open after the dissolution of the Académie) and finding new patrons. His designs for Oberkampf continued to be popular, reflecting perhaps a desire for escapism and the enduring appeal of nature even amidst political turmoil. While he did not embrace the Neoclassical style in his core work, his commitment to naturalism and detailed observation likely helped his art retain relevance. His son, Nicolas Jean Huet (sometimes called Huet the Younger), followed in his footsteps as an animal painter and notably participated as an artist in the scientific expedition accompanying Napoleon's campaign in Egypt, further linking the family name to the era's major events.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Jean-Baptiste Huet I occupies a respected place in French art history. He is recognized as a leading animal painter of his generation, bridging the gap between the grand manner of Oudry and the later flourishing of the genre in the 19th century with artists like Constant Troyon or Rosa Bonheur, though his direct influence on them might be less pronounced than his embodiment of the tradition. His pastoral scenes represent a charming and skillful interpretation of Rococo themes, infused with a personal sensitivity and a greater degree of naturalism than seen in Boucher.

His contributions to the decorative arts, particularly his designs for toiles de Jouy, are highly significant. He played a crucial role in defining the visual identity of these iconic textiles, demonstrating how fine art skills could be successfully adapted to industrial design. His prints and drawings further attest to his versatility and graphic talent. His work is represented in major museum collections worldwide, including the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Getty Museum, and various museums dedicated to decorative arts and textiles.

Huet's enduring appeal lies in the combination of technical skill, observational accuracy, and undeniable charm. His idealized yet closely observed depictions of animals and rural life continue to captivate viewers, offering a window into the tastes and sensibilities of late 18th and early 19th-century France. He remains a testament to the multifaceted nature of artistic practice during this era, excelling across painting, drawing, printmaking, and design.

Conclusion

Jean-Baptiste Huet I was more than just a painter of sheep and shepherds. He was a versatile and industrious artist who successfully navigated the transition from the Ancien Régime through the Revolution and into the Napoleonic era. Rooted in the Rococo tradition through his family and training, he developed a distinctive style characterized by naturalistic detail, particularly in his animal depictions, and gentle, pastoral charm. His significant contributions to printmaking and textile design, especially for the Oberkampf factory, underscore his adaptability and his engagement with the broader visual culture of his time. As a master animalier, a creator of idyllic landscapes, and an influential designer, Huet left an indelible mark on French art.