Jean-Michel Moreau (1741-1814), often distinguished by the appellation "le Jeune" (the Younger) to differentiate him from his elder brother, the landscape painter Louis-Gabriel Moreau, stands as one of the most significant and prolific graphic artists of 18th-century France. Born in Paris on March 26, 1741, and dying there in 1814, his life spanned a period of immense social, political, and artistic transformation, from the height of the Rococo to the Neoclassical era and the turmoil of the French Revolution and its aftermath. While he explored painting early in his career, Moreau le Jeune ultimately forged his reputation as a master draughtsman, etcher, and engraver, becoming perhaps the preeminent book illustrator of his time and a meticulous chronicler of French society.

Artistic Genesis and Early Training

Moreau was born into a milieu steeped in the arts. His father was a sculptor, and his mother practiced the delicate art of miniature painting. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his innate talents. His formal training began under the guidance of the painter and engraver Louis-Joseph Le Lorrain, an artist who would play a pivotal role in Moreau's early professional life. Le Lorrain recognized the young artist's potential, taking him on as a student and collaborator.

This apprenticeship led to a significant, albeit brief, chapter abroad. In 1758, Le Lorrain was appointed the first director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Saint Petersburg, Russia. He invited Moreau, then just seventeen, to accompany him. This journey marked a crucial step for Moreau, exposing him to a different cultural environment and offering him a prestigious early position.

The St. Petersburg Interlude

During his time in the Russian imperial capital, Moreau served as a professor of drawing at the nascent Academy of Fine Arts. This teaching role, undertaken at such a young age, speaks to his precocious abilities and the confidence Le Lorrain placed in him. While in Russia, Moreau continued to create art. Among his notable works from this period is a sensitive red-chalk portrait of Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. This drawing, now conserved in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris, showcases his skill in capturing likeness and character even in his youth.

However, Moreau's Russian sojourn was cut short. Following Le Lorrain's sudden death in 1759, Moreau decided to return to Paris. This return marked a turning point in his artistic direction.

A Decisive Shift: Embracing Graphic Arts in Paris

Upon resettling in Paris, Moreau made a conscious decision that would define his career. He largely abandoned painting, the medium often seen as the pinnacle of artistic achievement, to dedicate himself almost exclusively to drawing and printmaking, particularly etching and engraving for book illustration. This was not necessarily a step down, but rather a strategic move into a field where his talents for detailed observation, narrative clarity, and exquisite line work could truly flourish.

A crucial step in this new direction was joining the workshop of the highly respected engraver Jacques-Philippe Le Bas. Le Bas's studio was a major center for print production in Paris, known for its high-quality reproductive engravings after contemporary painters as well as original works. Working under Le Bas provided Moreau with invaluable technical refinement and connections within the Parisian art and publishing worlds.

Collaborations and the Parisian Art Scene

In Le Bas's workshop and throughout his career, Moreau interacted and collaborated with numerous leading artists and engravers. He produced engravings based on designs by prominent Rococo masters like François Boucher and Charles Eisen, as well as contemporaries like Hubert-François Gravelot and Charles Monet, particularly for illustrated editions like Ovid's Metamorphoses. He also worked alongside skilled engravers such as Charles-Nicolas Cochin II, another dominant figure in French graphic arts and illustration.

His circle included artists working in various styles. While deeply engaged with the elegant Rococo aesthetic prevalent in his youth, exemplified by artists like Jean-Honoré Fragonard and Antoine Watteau (whose influence lingered), Moreau's career also overlapped with the rise of Neoclassicism, championed by Jacques-Louis David. Moreau navigated these shifting tastes, adapting his style while retaining his unique voice. He collaborated with the engraver Pietro Antonio Martini on certain projects and maintained professional relationships within the broader artistic community, which included figures like Jean-Baptiste Greuze, known for his sentimental genre scenes, and history painters like Carle Van Loo. His brother, Louis-Gabriel Moreau, focused on landscapes, carving his own niche. Moreau le Jeune also engraved works after artists like Jean-Baptiste Oudry. His interactions extended to fellow engravers like Augustin de Saint-Aubin, highlighting the collaborative nature of printmaking.

The Master Illustrator

Moreau le Jeune's reputation soared primarily due to his extraordinary work as an illustrator. He became the artist of choice for publishers undertaking ambitious illustrated editions of major literary works. His contributions graced the pages of collected editions of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, Molière, and the fables of Jean de La Fontaine. He provided etchings for the Comte de Caylus's Recueil d'antiquités égyptiennes, étrusques, grecques et romaines and, significantly, contributed plates to Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert's monumental Encyclopédie, a cornerstone of the Enlightenment.

His illustrations were prized for their accuracy, elegance, and narrative power. He possessed an uncanny ability to translate complex texts into compelling visual scenes, capturing the essence of characters, settings, and dramatic moments with remarkable finesse. His work for Jean-Benjamin de Laborde's Choix de chansons mises en musique (often referred to as Chants de Laborde) further cemented his status.

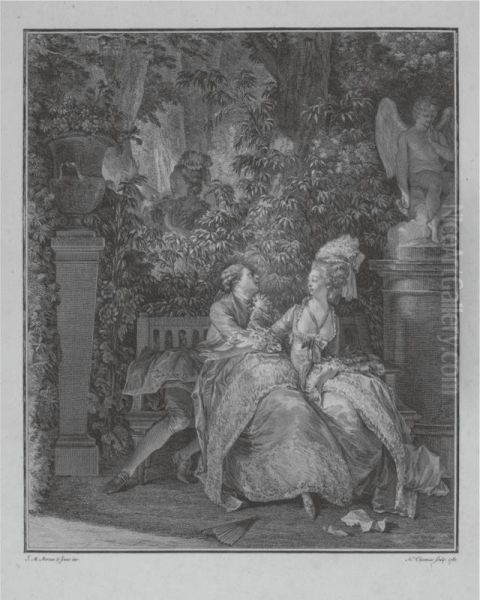

Chronicler of Society: The Monument du Costume

Among Moreau's most celebrated achievements are the series of prints often collectively known as the Monument du Costume. These suites of engravings, particularly the second and third series executed in the 1770s and 1780s (Suite d'estampes pour servir à l'histoire des modes et du costume en France and Troisième Suite d'Estampes), meticulously document the fashions, interiors, and daily lives of the French aristocracy in the final years of the Ancien Régime.

These prints go beyond mere fashion plates. They are intimate glimpses into a specific world, depicting activities like the lever (waking ritual), private concerts, promenades, and social visits. Moreau's keen eye captures the nuances of gesture, the textures of luxurious fabrics, the details of ornate furniture, and the subtle interactions between figures. These works serve as invaluable historical documents, offering a vivid portrait of a society on the cusp of radical change. The earlier suite had featured designs by Sigmund Freudenberger, but Moreau's own designs for the later series are considered masterpieces of the genre.

Artistic Style: Elegance and Observation

Moreau le Jeune's style is characterized by its remarkable synthesis of Rococo grace and Neoclassical clarity. From the Rococo, he inherited a love for flowing lines, delicate ornamentation, and an overall sense of elegance and lightness, particularly evident in his depiction of women and fashionable attire. His figures often possess a balletic poise, reminiscent of the fêtes galantes of Watteau or the charming scenes of Boucher and Fragonard.

However, his work also demonstrates a rigorous attention to detail and a commitment to accurate observation that aligns with the burgeoning Neoclassical sensibility. His line work is precise and controlled, defining form with clarity. He masterfully handled complex compositions, arranging multiple figures within detailed architectural or natural settings. His ability to render textures – the sheen of silk, the softness of fur, the crispness of paper – in monochrome etching is extraordinary.

Later in his career, particularly in illustrations for more serious subjects like the Bible (such as the noted illustration for Matthew 4:10, depicting Christ's temptation), a greater emphasis on dramatic composition and lighting can be observed, reflecting Neoclassical tastes. The use of strong diagonals and chiaroscuro effects in such works enhances their emotional impact, demonstrating his versatility. He often drew inspiration from classical sculpture for the poses and drapery of his figures.

Technical Prowess in Etching and Engraving

Moreau was a consummate technician in the graphic arts. He primarily worked in etching, often finishing his plates with burin engraving to achieve finer details and tonal variations. His mastery lay in his ability to create a sense of light, space, and texture using only line. His drawings, often executed in pen and ink with wash, served as the basis for his prints and are themselves highly regarded works of art, showcasing his fluid draughtsmanship and compositional skill.

His meticulous approach ensured that his prints were not just illustrations but sophisticated works of art in their own right. He understood the potential of the engraved line to convey not only form but also emotion and atmosphere, making him a leader in the field alongside contemporaries like Cochin and Saint-Aubin.

Official Recognition and Revolutionary Times

Moreau's talent did not go unnoticed by the establishment. In 1770, he was appointed "Dessinateur des Menus Plaisirs du Roi" (Draughtsman of the King's Lesser Pleasures), a prestigious position that involved designing costumes, ephemera, and decorations for court ceremonies, festivities, and theatrical performances. This role placed him at the heart of official artistic life.

Further recognition came in 1789, a year of profound upheaval, when he was received as a full member of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. During the French Revolution, Moreau adapted to the changing political climate. He seems to have supported the revolutionary ideals initially and continued to work, producing prints related to contemporary events. His focus shifted somewhat, reflecting the new civic virtues and historical consciousness of the era.

Later Career and Legacy

Moreau continued to work prolifically into the early 19th century, adapting his style to the prevailing Neoclassical and Empire aesthetics, though perhaps his most iconic work remains rooted in the pre-revolutionary period. He illustrated editions of classical authors and continued to receive commissions, maintaining his reputation as a leading graphic artist. He died in Paris in 1814, the year Napoleon abdicated for the first time.

Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune's legacy is multifaceted. He was arguably the most important French book illustrator of the 18th century, setting a standard for elegance, detail, and narrative coherence. His prints, especially the Monument du Costume, provide an unparalleled visual record of French aristocratic society in its twilight years. His technical mastery of etching and engraving influenced subsequent generations of printmakers. While perhaps overshadowed in popular memory by painters like Boucher, Fragonard, or David, Moreau le Jeune remains a pivotal figure for understanding the art, culture, and social history of 18th-century France, a meticulous observer who captured the spirit of his age with unparalleled grace and precision in line. His work bridges the Rococo and the Neoclassical, much like the painter Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, offering a unique perspective on a world undergoing profound transformation.