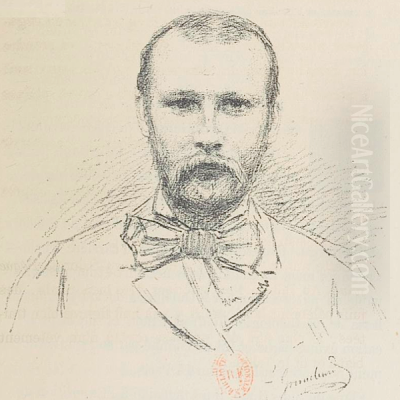

Johannes Martin Grimelund (1842-1917) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th and early 20th-century Norwegian art. A dedicated painter and an innovative printmaker, Grimelund carved a niche for himself through his evocative depictions of the Norwegian landscape, particularly his masterful renderings of snow and coastal scenes. His career spanned a period of profound artistic transformation in Norway, as artists sought to define a national identity through their work, moving from the tenets of Romanticism towards Realism and Naturalism, with glimpses of burgeoning modern sensibilities. Grimelund's journey through various artistic centers of Europe, his technical proficiency, and his commitment to capturing the unique atmosphere of his homeland make him a compelling subject for study.

Early Artistic Formation in Christiania

Born in 1842, Johannes Martin Grimelund's artistic inclinations emerged in a Norway that was increasingly fostering its own cultural institutions. His formal artistic education began in Christiania (now Oslo) at the Eckersberg Art School (Eckersbergs malerskole). This school, though perhaps not as internationally renowned as academies in Paris or Düsseldorf at the time, played a crucial role in training a generation of Norwegian artists. It provided a foundational grounding in drawing and painting, likely emphasizing academic principles while also being open to the burgeoning interest in depicting local scenery and life.

The artistic environment in Christiania during Grimelund's formative years was shaped by the legacy of painters like Johan Christian Dahl (J.C. Dahl), often considered the father of Norwegian landscape painting, and his contemporary Thomas Fearnley. Though Dahl primarily worked abroad, his influence in promoting a distinctively Norwegian landscape art was pervasive. Artists like Knud Bergslien, who was a prominent figure and teacher in Christiania, would have been part of the milieu Grimelund experienced. The emphasis was shifting towards a more direct observation of nature, a trend that would become central to Grimelund's own practice.

The Karlsruhe Connection: Under the Tutelage of Hans Gude

A pivotal moment in Grimelund's development was his decision to further his studies abroad. He traveled to Germany and enrolled in the studio of Hans Fredrik Gude in Karlsruhe. Gude was one of the most influential Norwegian landscape painters of his generation, a leading figure of Norwegian National Romanticism, and a highly respected teacher. He had previously taught at the Düsseldorf Academy, which was a magnet for Scandinavian artists, before taking up a professorship in Karlsruhe.

Studying under Gude would have exposed Grimelund to a rigorous approach to landscape painting, one that combined meticulous observation of nature with an ability to convey its grandeur and specific atmospheric qualities. Gude was known for encouraging his students to engage in plein air (outdoor) sketching, a practice that was becoming increasingly important across Europe, championed by artists like those of the Barbizon School in France, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot and Théodore Rousseau. This direct engagement with the subject was crucial for capturing the fleeting effects of light and weather.

In Karlsruhe, Grimelund would have been part of a vibrant community of artists, many of them Scandinavian. Gude's studio attracted numerous talents who would go on to make significant contributions to Norwegian art, including figures like Frits Thaulow (though Thaulow's main period with Gude was slightly later), Kitty Lange Kielland, and Eilif Peterssen. The exchange of ideas and the shared pursuit of artistic excellence in such an environment would have been immensely stimulating for the young Grimelund. The Düsseldorf School's influence, with its emphasis on detailed realism and often dramatic compositions, would still have been palpable, even as Gude and his students pushed towards a more naturalistic and less overtly romanticized depiction of landscapes.

A Norwegian Vision: Themes and Subjects

Upon completing his studies, Grimelund embarked on an international artistic career, yet his heart and his primary subject matter remained firmly rooted in Norway. He became particularly renowned for his landscapes, which captured the diverse beauty of the Norwegian terrain. Coastal scenes, with their dramatic interplay of sea, sky, and rugged shorelines, were a recurring theme. He was adept at conveying the unique light of the Nordic latitudes, from the crisp clarity of a summer morning to the melancholic glow of twilight.

His depictions of fishing villages, such as the work titled Village of fisher at dusk (1904), likely housed in a regional collection like the Nordfjord Folkemuseum or a similar institution dedicated to Norwegian heritage, showcase his ability to imbue everyday scenes with a quiet dignity and atmospheric depth. These paintings often reflect the close relationship between the Norwegian people and their natural environment, a central theme in the art of the period.

Grimelund also excelled in portraying winter landscapes. Snow, in its myriad forms and textures, presented a unique challenge that he met with considerable skill. His snow scenes are not merely white expanses but are filled with subtle gradations of color, capturing the way light reflects and refracts on frozen surfaces. Works like Rue de village sous la neige au soleil couchant (1904), which found its way into the collection of the Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris, attest to his international recognition and his particular affinity for these wintry subjects. This painting, with its title suggesting a village street under snow at sunset, would have allowed him to explore the warm hues of the setting sun contrasting with the cool tones of the snow, a motif favored by many Scandinavian painters. Another notable work, Summer Morning at Molde, highlights his versatility in capturing different seasons and moods.

Mastery of Technique: Painting and Printmaking

Johannes Martin Grimelund was not only a painter but also a skilled printmaker, an area where he demonstrated particular innovation. His approach to printmaking, especially his color prints, was distinctive. He was known to employ a mixed ink technique, particularly for his snow scenes. This involved carefully applying different colored inks to the same copper plate before printing. The result was a soft, almost powdery effect, where colors could blend subtly on the paper, perfectly suited to rendering the delicate textures and diffused light of a snow-covered landscape. This technique allowed for a painterly quality in his prints, moving beyond simple line work to achieve rich tonal variations.

He also utilized the "encrage à la poupée" (inking with a doll) method. This intricate intaglio technique involves applying different colors to different parts of a single printing plate using small dabbers or "poupées" made of cloth. This allows the artist to print multiple colors in a single impression, requiring great skill and precision in both the inking and wiping of the plate. The resulting prints often have a remarkable luminosity and depth of color, with soft transitions between hues. Grimelund's mastery of these complex color printmaking techniques set him apart and contributed significantly to his reputation. His prints were not mere reproductions of his paintings but original artistic expressions in their own right.

His painting style, while rooted in the Realist-Naturalist tradition, often displayed a sensitivity to light and atmosphere that bordered on the poetic. He paid close attention to the accurate depiction of natural phenomena, but his best works also convey a strong sense of mood and place. He was less inclined towards the dramatic pathos of high Romanticism seen in some of Gude's earlier works or those of artists like August Cappelen, and more towards a faithful yet lyrical interpretation of the observed world, akin to the sensibilities of artists like Amaldus Nielsen, another fine Norwegian coastal painter.

The Parisian Sojourn and International Career

Like many ambitious artists of his time, Grimelund spent a period living and working in Paris. The French capital was the undisputed center of the art world in the late 19th century, a melting pot of styles and ideas. While there is no strong evidence to suggest that Grimelund fully embraced the radical innovations of Impressionism, then in its heyday with artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Edgar Degas, he would undoubtedly have been exposed to this and other avant-garde movements.

His time in Paris likely broadened his artistic horizons and provided opportunities to exhibit his work to an international audience. The fact that a work like Rue de village sous la neige au soleil couchant entered a prestigious Parisian collection like the Petit Palais indicates that his art found appreciation beyond Scandinavia. His style, with its emphasis on naturalistic depiction and atmospheric effects, would have found common ground with certain strands of French landscape painting that ran parallel to Impressionism, such as the continuing legacy of the Barbizon school or the works of artists like Jean-Charles Cazin.

His international career also involved correspondence and interactions that shed light on his engagement with the broader art world. For instance, he corresponded with Albert Cammermeyer, a Norwegian bookseller and art dealer, regarding the sale and promotion of works by Norwegian artists. This suggests an active interest in the professional aspects of art and the welfare of his fellow countrymen in the arts.

Interactions and Collaborations: A Networked Artist

Grimelund was not an isolated figure. His training and career brought him into contact with numerous other artists. His relationship with Otto Sinding, another prominent Norwegian painter, is particularly noteworthy. Sinding, known for his dramatic historical and landscape paintings, apparently saw potential in Grimelund and expressed a desire to guide the younger artist towards a career in outdoor painting (friluftsmaleri). This aligns perfectly with the prevailing trends and Grimelund's own inclinations. There is even mention of a collaborative work, Friluftsmalere (Outdoor Painters), by Grimelund and Sinding, underscoring their shared artistic interests.

His correspondence also reveals connections with other artists, including Victor von Gegerfelt, a Swedish landscape painter, and Widolf Engström-Ahrenberg. Such exchanges were vital for artists, especially those working internationally, allowing them to share news, discuss artistic matters, and maintain a sense of community. These interactions place Grimelund within a network of Scandinavian and European artists who were navigating the evolving art scene of the late 19th century. Other Norwegian contemporaries whose paths he might have crossed, or whose work he would have known, include Erik Werenskiold and Christian Krohg, leading figures in the shift towards Realism in Norway, and perhaps even the younger Edvard Munch, whose early work also focused on Norwegian landscapes and scenes of daily life, albeit with a growing psychological intensity.

Representative Works in Focus

While specific visual details of all his works are not readily available without direct images, we can infer their qualities from their titles and Grimelund's known style.

Village of fisher at dusk (1904) would likely depict a coastal settlement as evening approaches. One can imagine the soft, fading light casting long shadows, the fishing boats pulled ashore or bobbing gently in the harbor, and the warm glow from windows hinting at life within the homes. Grimelund's skill would lie in capturing the specific quality of Norwegian twilight, the subtle colors in the sky and their reflection on the water, and the overall atmosphere of tranquility or perhaps the hardy resilience of a fishing community.

Rue de village sous la neige au soleil couchant (1904) presents a classic winter motif. The "soleil couchant" (setting sun) offers a rich palette of oranges, pinks, and purples to contrast with the blues and whites of the snow. The "rue de village" (village street) provides a compositional structure, perhaps leading the eye past snow-laden roofs and frosted trees towards the vibrant sunset. His mixed-ink or à la poupée printmaking techniques would be particularly effective for such a subject, allowing for both the crispness of snowy textures and the soft blending of sunset hues.

Summer Morning at Molde would offer a contrast, showcasing the lushness and clarity of a Norwegian summer. Molde, known for its beautiful views of fjords and mountains, would provide a stunning backdrop. One might expect vibrant greens, the sparkling blue of the fjord, and a clear, bright light characteristic of a Nordic summer morning. This work would demonstrate his ability to adapt his palette and technique to different seasons and atmospheric conditions.

Legacy and Place in Norwegian Art History

Johannes Martin Grimelund passed away in 1917. He left behind a body of work that contributes to our understanding of Norwegian landscape painting and printmaking during a crucial period of national and artistic self-discovery. While he may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his contemporaries like Frits Thaulow or Edvard Munch, his dedication to his craft, his technical innovations in printmaking, and his sensitive portrayals of the Norwegian environment secure his place in his country's art history.

He was also a teacher, and in this role, he would have passed on his knowledge and skills to a younger generation of artists, contributing to the continuity and development of Norwegian art. His work exemplifies the transition from the more overtly romanticized landscapes of the mid-19th century towards a more direct, naturalistic, yet still deeply felt, engagement with nature. He captured not just the topography of Norway, but also its soul, its light, and its atmosphere.

His prints, in particular, represent a significant achievement. At a time when color printmaking was undergoing exciting developments across Europe, influenced partly by the influx of Japanese Ukiyo-e prints, Grimelund's sophisticated use of techniques like encrage à la poupée demonstrates his engagement with contemporary artistic possibilities. These works deserve wider recognition for their technical finesse and aesthetic appeal.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Johannes Martin Grimelund was an artist deeply connected to his Norwegian roots, yet open to the broader currents of European art. His studies with Hans Gude provided a strong foundation, while his experiences in Paris and his interactions with fellow artists enriched his practice. He excelled in capturing the unique character of the Norwegian landscape, from its rugged coasts to its snow-covered villages, demonstrating a particular sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His innovative approach to color printmaking further distinguishes his artistic output. As an art historian, one appreciates Grimelund for his consistent vision, his technical skill, and his contribution to the enduring tradition of landscape art in Norway, a tradition that continues to celebrate the profound beauty and distinctive character of the Nordic world. His works serve as a visual testament to a specific time and place, rendered with an honesty and artistry that still resonates today.