An Introduction to the Painter of Night

John Atkinson Grimshaw, born in Leeds on September 6, 1836, stands as one of the most distinctive and atmospheric painters of the Victorian era. Though often working outside the mainstream London art scene for much of his career, he carved a unique niche for himself, becoming renowned primarily for his evocative nocturnes – scenes of urban streets, suburban lanes, and bustling docks bathed in the ethereal glow of moonlight or the warmer, more localised radiance of gaslight. His work captures a specific mood, a blend of melancholy, mystery, and the quiet beauty found in the industrialising landscapes of 19th-century Britain. He passed away in Leeds on October 13, 1893, leaving behind a body of work that continues to fascinate viewers with its meticulous detail and haunting ambiance.

Grimshaw was fundamentally an English painter, deeply rooted in the landscapes and cityscapes of the North of England, although he also depicted scenes in London, Glasgow, and other locations. His style, while grounded in the detailed realism popular during the Victorian period, possesses a strong Romantic sensibility, particularly in its focus on atmosphere, emotion, and the effects of light. He is often associated with the later phases of Victorian painting, touching upon elements of Aestheticism in some works, but remaining largely independent of the major artistic movements like Impressionism that were developing concurrently in France.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born into a relatively modest family in Leeds – his father variously described as a policeman or a grocer, and later working for the railway – young John Atkinson Grimshaw initially followed a conventional path. He began working as a clerk for the Great Northern Railway, a secure but likely unfulfilling position for someone harbouring artistic ambitions. His interest in art developed early, possibly influenced by the burgeoning visual culture of the time and the accessibility of prints and exhibitions.

The pivotal moment came around 1861 when, at the age of 24 or 25, Grimshaw made the bold decision to abandon his railway career and dedicate himself entirely to painting. This was reportedly met with disapproval from his parents, reflecting the common view at the time that art was a precarious and perhaps unsuitable profession, especially for someone without formal training or connections. He had married his cousin Frances Theobald (Fanny) in 1858, and the responsibility of a growing family likely added pressure to his decision.

Crucially, Grimshaw was almost entirely self-taught. He did not attend the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London or receive formal instruction from established masters. Instead, he learned his craft through intense observation, practice, and likely by studying the works of other artists, perhaps including the highly detailed style advocated by the critic John Ruskin and exemplified by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, whose work was gaining prominence during his formative years. This self-reliance shaped his unique approach and technical methods throughout his career.

Forging a Signature Style: From Detail to Dusk

Grimshaw's earliest works, dating from the early 1860s, show a clear affinity with the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic. Paintings of still lifes, birds' nests, and detailed woodland scenes demonstrate a commitment to meticulous observation and vibrant colour, echoing the principles championed by artists like John Everett Millais and William Holman Hunt. These early pieces showcase his innate talent for rendering texture and detail with remarkable precision.

However, Grimshaw soon began to move beyond these tightly focused natural studies. He turned his attention increasingly towards landscapes and, significantly, towards the effects of light and atmosphere at different times of day. By the late 1860s and early 1870s, he was developing the subject matter that would define his career: moonlit scenes. He began painting the suburban lanes and mansions around Leeds, often featuring solitary figures, autumnal foliage, and the distinctive silhouettes of trees against a luminous night sky.

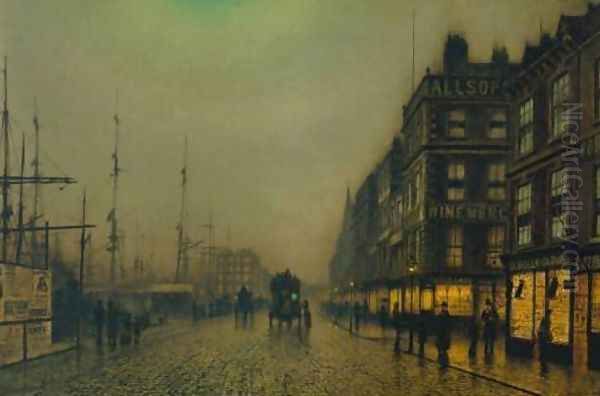

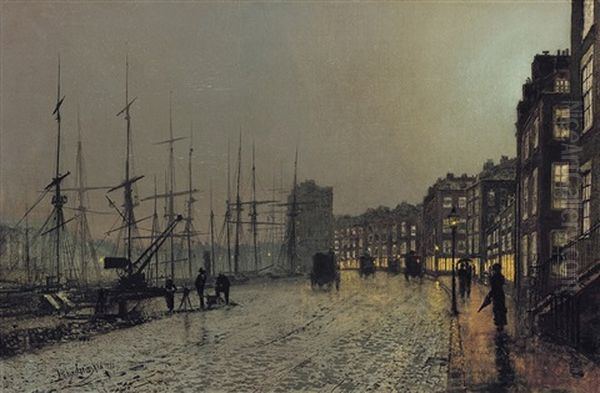

His fascination with docks and shipping also emerged during this period. He painted harbours in northern cities like Hull, Whitby, and Scarborough, and later expanded his range to include major ports such as Liverpool, Glasgow, and London. These dock scenes became a cornerstone of his output, allowing him to explore the complex interplay of moonlight on water, the reflections of gas lamps from pubs and offices lining the quays, and the intricate rigging of ships against the night sky. This focus on the specific ambiance of twilight and night set him apart from most of his contemporaries.

The Nocturnes: Capturing the Victorian Night

The term "nocturne," popularised in art by James McNeill Whistler, perfectly describes Grimshaw's most characteristic works. While Whistler's nocturnes were often exercises in tonal harmony and abstraction, Grimshaw's were rooted in a detailed, almost photographic realism, yet imbued with a powerful sense of mood and poetry. He became a master of depicting the subtle gradations of light in the night sky, from the cold, silvery light of the full moon to the softer glow on cloudy nights.

His urban nocturnes often feature wet, reflective streets and pavements, mirroring the gaslights and moonlight, adding depth and luminosity to the scenes. Cobblestones glisten, puddles reflect the sky, and the damp air seems palpable. Figures, when present, are often solitary or in small groups, dwarfed by the surrounding architecture or the vastness of the night, contributing to a sense of quiet introspection or even loneliness. Titles like Liverpool Quay by Moonlight (1887), Shipping on the Clyde (c. 1881), and Blackman Street, London (1885) exemplify this genre.

Grimshaw's skill lay in his ability to combine topographical accuracy with emotional resonance. His depictions of cities like Leeds, Liverpool, or Glasgow are recognisable, yet transformed by the magic of the night. He captured the specific atmosphere of the Victorian city after dark – a world illuminated by the relatively new technology of gaslight, which created pools of warm light contrasting with the cool, pervasive moonlight. This juxtaposition of natural and artificial light is a hallmark of his work.

There exists a famous, possibly apocryphal, anecdote regarding Whistler's reaction to Grimshaw's work. Whistler, known for his own atmospheric nocturnes, is reputed to have said, "I considered myself the inventor of Nocturnes until I saw Grimmy's moonlit pictures." Whether true or not, it highlights the perceived connection and potential rivalry between the two artists exploring similar themes, albeit with vastly different stylistic approaches. Grimshaw's detailed rendering stood in stark contrast to Whistler's suggestive tonalism.

Technique and the Photographic Eye

One of the recurring discussions surrounding Grimshaw's work concerns his methods. It is widely believed, and supported by some evidence and analysis of his paintings, that he utilised optical aids, such as the camera obscura or photographs, to help achieve the remarkable accuracy and detail in his compositions. The camera obscura could project an image onto a surface, allowing an artist to trace outlines and establish perspective with great precision. Photography was also becoming increasingly accessible during his lifetime.

This use of mechanical aids was controversial among some contemporaries. Critics occasionally dismissed his work as lacking the "touch" or "feeling" of freehand drawing and painting, suggesting it was too reliant on a "mechanical" process. They argued that true artistry lay in the interpretation and rendering by hand and eye alone, without such assistance. This debate touches upon broader questions about the relationship between art, technology, and realism in the 19th century.

However, to attribute Grimshaw's success solely to technical aids would be a gross oversimplification. Even if he used projections or photographs for compositional structure or detail placement, the final painted surface, the subtle mixing of colours to achieve specific light effects, the rendering of atmosphere, and the overall artistic vision were entirely his own. His mastery of oil paint, his ability to depict mist, moonlight, and reflections with such conviction, required immense skill and sensitivity developed through years of practice. His brushwork, while often smooth and detailed, was highly controlled and effective in conveying the desired textures and light.

Beyond the Nocturnes: Diverse Subjects

While Grimshaw is overwhelmingly famous for his nocturnes, his artistic output was more varied. He continued to paint daylight landscapes throughout his career, often favouring autumnal scenes with their rich colours and mellow light. Works like Stapleton Park, near Pontefract or scenes depicting country lanes under golden afternoon sun show his versatility and appreciation for the natural world in all its moods. These landscapes often share the quiet, slightly melancholic atmosphere found in his night scenes.

He also produced a number of interior scenes, sometimes featuring solitary female figures in aesthetically decorated rooms, perhaps reading or playing music. These works connect him to the Aesthetic Movement's interest in beauty, mood, and decorative detail, and show parallels with artists like James Tissot, whose depictions of contemporary life and fashion were highly popular. Grimshaw's interiors often explore complex indoor lighting effects, contrasting lamplight with firelight or daylight filtering through windows.

Less common, but significant, are his forays into literary, historical, or imaginative subjects. He painted scenes inspired by the poetry of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, such as illustrations for Enoch Arden. He also created a small number of "fairy paintings," such as Iris or Spirit of the Night, which tap into the Victorian fascination with the supernatural and the unseen world, echoing themes explored by artists like Richard Dadd or John Anster Fitzgerald, albeit rendered with Grimshaw's characteristic atmospheric lighting. These works demonstrate a broader imaginative range beyond his typical urban and landscape views.

His own home, Knostrop Hall, an old manor house on the outskirts of Leeds which he rented from the 1870s, became a recurring subject. He painted it numerous times, often in the early morning or late evening, capturing its aged brickwork and surrounding gardens under different atmospheric conditions. These paintings have a personal, almost portrait-like quality, documenting his domestic environment.

Life in Leeds and Scarborough: Success and Struggles

Grimshaw's life was centred primarily in Yorkshire. After marrying Fanny, the couple had a large family, eventually numbering as many as fifteen children, although tragically, several died in infancy or childhood – a common occurrence in the Victorian era. The need to support this large family undoubtedly drove his prolific output and perhaps influenced his focus on commercially appealing subjects like the nocturnes.

Despite his growing reputation, particularly in the North of England, Grimshaw experienced periods of financial difficulty. Records indicate significant debts in the late 1870s, leading to a temporary retreat from Knostrop Hall. However, his fortunes seem to have improved in the 1880s. He was able to maintain a London studio in Chelsea for a time, placing him closer to the capital's art market, and significantly, he later acquired or rented a second imposing home, Castle-by-the-Sea, in the fashionable resort town of Scarborough.

His connection to Leeds remained strong throughout his life. He was involved in the local art scene, exhibiting with the Leeds Fine Arts Club and the Leeds Mechanics' Institute. His detailed depictions of Leeds streets, such as Briggate or Park Row, provide valuable historical records of the city during its industrial peak, captured through his unique artistic lens.

Several of his children also became artists, including Arthur E. Grimshaw (1864–1913), Louis H. Grimshaw (1870–1943), Wilfred Grimshaw (1871–1937), and Elaine Grimshaw (1877-1970). They often painted in styles reminiscent of their father's, sometimes leading to confusion in attribution, but also establishing something of an artistic dynasty focused on similar atmospheric themes.

Artistic Context and Contemporaries

Placing Grimshaw within the broader context of Victorian art reveals his unique position. He was contemporary with the later Pre-Raphaelites like Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, but his style diverged significantly from their medievalising and decorative tendencies, though an early influence is clear. He shared the Victorian love for detail and narrative potential with popular painters like William Powell Frith, known for his bustling contemporary scenes like Derby Day, but Grimshaw's focus was narrower, more atmospheric, and less overtly narrative.

His closest parallel, as noted, is James McNeill Whistler, particularly in their shared interest in nocturnes. However, their philosophies and techniques differed markedly. Whistler sought "art for art's sake," prioritising aesthetic harmony and tonal relationships over literal depiction. Grimshaw, while highly atmospheric, remained committed to a form of poetic realism, carefully rendering the specific details of place and time.

He was also working at a time when Impressionism was revolutionising art in France, with artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro exploring the fleeting effects of light with broken brushwork and bright palettes. Grimshaw seems largely untouched by Impressionist technique, adhering to a smoother finish and more traditional compositional structures. His approach to light, while masterful, was about capturing sustained mood rather than momentary effects.

Other relevant contemporaries include Albert Moore, whose classical figures in aesthetic interiors share a certain quietude with some of Grimshaw's work, and perhaps Gustave Doré, whose dramatic engravings of London's dark alleys and industrial scenes captured a similar urban atmosphere, albeit with a more gothic sensibility. Earlier British masters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable had, of course, explored atmospheric effects and the power of landscape, potentially providing a deeper historical context for Grimshaw's focus on light and mood. The influential critic John Ruskin, while primarily championing the Pre-Raphaelites and Turner, created a climate where detailed observation of nature and atmosphere was highly valued.

Grimshaw's relationship with the London art establishment, centred around the Royal Academy, appears to have been limited. While he did exhibit there occasionally, he was never a member and seems to have found more consistent patronage and appreciation in the industrial cities of the North. His relative isolation from London may have allowed him to develop his distinctive style without being overly swayed by prevailing academic trends.

Critical Reception and Enduring Legacy

During his lifetime, Grimshaw achieved considerable commercial success, particularly from the 1870s onwards. His moonlit scenes were popular with the industrialists and middle-class collectors of the North, who likely appreciated the recognisable local settings combined with their romantic atmosphere. He was able to command respectable prices for his work and support a large family and impressive households.

However, critical reception, especially from London-based critics, was sometimes mixed or dismissive. His reliance on a popular formula (the nocturne), his perceived use of technical aids, and his focus on realism rather than the more avant-garde trends emerging towards the end of the century meant he was not always taken seriously by the art establishment. He was sometimes seen as a provincial painter, albeit a highly skilled one.

After his death in 1893 from tuberculosis, Grimshaw's reputation declined, along with that of many Victorian narrative and realist painters, as tastes shifted towards Modernism. For much of the early 20th century, his work was largely overlooked by major museums and art historians.

The revival of interest in Grimshaw began in the mid-20th century. Exhibitions and scholarly articles started to re-evaluate his contribution, appreciating his unique vision, his technical brilliance, and the evocative power of his paintings. Collectors began to seek out his work again, and prices at auction started to rise significantly, particularly from the 1960s onwards. Today, he is recognised as a major figure within Victorian art.

His legacy rests on his unparalleled ability to capture the specific atmosphere of the Victorian night. His paintings are more than just topographical records; they are poetic interpretations of urban and suburban life, imbued with a sense of mystery, beauty, and the quiet melancholy of the hours after dark. He documented a world undergoing rapid change, where gaslight met moonlight, and nature persisted alongside industrial expansion. His work offers a unique window onto the visual and emotional landscape of 19th-century Britain, rendered with a skill and sensitivity that continues to resonate with audiences today. His paintings are now held in numerous public collections in the UK and internationally, securing his place as the definitive master of the Victorian nocturne.

Conclusion: The Painter of Moonlight

John Atkinson Grimshaw remains a compelling figure in British art history. A largely self-taught artist from Leeds, he developed a highly distinctive style focused on the evocative power of moonlight and gaslight in urban and suburban settings. His nocturnes, characterised by meticulous detail, reflective surfaces, and a palpable sense of atmosphere, capture a unique blend of realism and romanticism. While sometimes criticised for his methods or overlooked by the mainstream art world during parts of his career and after his death, his work has enjoyed a significant revival. Today, Grimshaw is celebrated for his technical mastery, his unique subject matter, and his ability to convey the haunting beauty and quiet melancholy of the Victorian night. His paintings stand as enduring testaments to a specific time and place, transformed by the artist's singular vision into scenes of poetic resonance.