John Burr, born in Edinburgh in 1831 and passing away in London in 1893, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. A painter of considerable skill and sensitivity, he dedicated much of his career to capturing the nuances of everyday life, particularly the domestic scenes and rural existence of Scotland and, later, England. His work, characterized by its gentle realism, warmth, and often a touch of pathos or quiet humor, found favor with a Victorian public increasingly drawn to narrative and anecdotal art. Burr was part of a generation of Scottish artists who, while trained in their homeland, often sought wider recognition and patronage in the burgeoning art market of London.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Edinburgh

John Burr's artistic journey began in the historic city of Edinburgh, a vibrant cultural hub in 19th-century Scotland. Born into a family that would also produce another notable artist, his younger brother Alexander Hohenlohe Burr (1835-1899), John's early environment likely fostered his artistic inclinations. The crucial step in his formal training was his enrollment at the Trustees' Academy in Edinburgh. This institution was paramount in the development of Scottish art, having nurtured talents such as Sir David Wilkie, Sir Henry Raeburn, and William Allan before him.

At the Trustees' Academy, under the tutelage of masters like Robert Scott Lauder, Burr would have received a rigorous grounding in drawing, anatomy, and composition. Lauder, in particular, was influential in shaping a generation of Scottish painters, encouraging a focus on character, narrative, and a rich, painterly technique. The curriculum would have emphasized drawing from the antique and the life model, instilling a discipline that underpinned Burr's later facility in depicting the human form and creating believable genre scenes. It was during these formative years that he began to hone his observational skills, an essential attribute for a painter who would later specialize in the intimate moments of daily existence.

His early works, even before his move to London, began to show a preference for subjects drawn from his immediate surroundings. He painted portraits and local landscapes, but the inclination towards genre painting – scenes of ordinary people in everyday activities – was already becoming apparent. In 1856, John Burr made his debut at the prestigious Royal Scottish Academy (RSA), an important milestone for any aspiring Scottish artist, signaling his entry into the professional art world of his native country. This initial recognition would have been encouraging, setting the stage for a career that would see him exhibit widely.

The Move to London and Flourishing Career

Around 1861, John Burr, accompanied by his brother Alexander, made the pivotal decision to relocate from Edinburgh to London. This move was a common trajectory for ambitious Scottish artists of the period. London, as the heart of the British Empire, offered a larger, more diverse art market, more exhibition opportunities, and a greater chance of securing patronage and critical attention. The brothers initially shared a studio, and both began to establish themselves within the London art scene, though John generally achieved a higher profile.

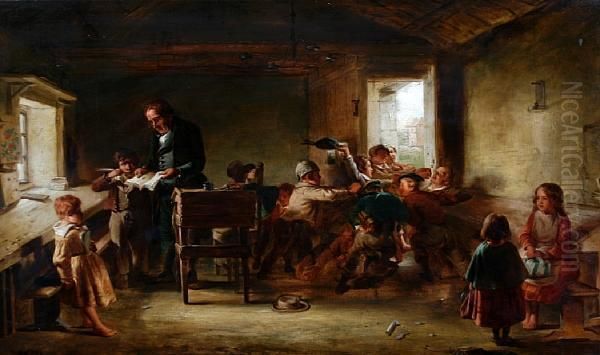

Once in London, John Burr continued to refine his focus on genre subjects. His paintings often depicted cottage interiors, scenes of childhood, the lives of the rural poor, and moments of quiet domesticity. These themes resonated strongly with Victorian sensibilities, which valued narratives of home, family, virtue, and simple pleasures. Burr's approach was characterized by a sympathetic and often tender portrayal of his subjects, avoiding overt moralizing but imbuing his scenes with genuine human feeling.

He became a regular exhibitor at major London venues, including the Royal Academy of Arts, the British Institution, and the Society of British Artists (SBA) in Suffolk Street. His participation in these exhibitions was crucial for building his reputation. Notably, his connection with the Society of British Artists deepened over time; he was elected a member and eventually served as its President from 1881, a testament to the respect he commanded among his peers. This position also placed him in a lineage that included artists like James McNeill Whistler, who would later famously, and controversially, lead the SBA.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Influences

John Burr's artistic style is best described as a form of Victorian genre painting with a strong narrative element, rooted in the Scottish tradition of detailed observation and character study. His technique was meticulous, with careful attention paid to the rendering of figures, fabrics, and the details of domestic interiors or rural settings. While not an innovator in the avant-garde sense, his strength lay in the consistent quality of his execution and the emotional resonance of his chosen subjects.

His color palette was generally warm and harmonious, often employing rich browns, reds, and earthy tones, which contributed to the cozy and intimate atmosphere of many of his scenes. He demonstrated a keen understanding of light and shadow, using it to model forms effectively and to create a sense of depth and realism. While distinct from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in its overall aims, some of Burr's work shares a Victorian concern for truth to nature and detailed finish, a characteristic also seen in the work of some of his Scottish contemporaries who were influenced by Pre-Raphaelite ideals, such as William Dyce or Joseph Noel Paton, albeit in different thematic contexts.

Thematically, Burr excelled in capturing the small, often unrecorded, moments of life. Children were frequent subjects, depicted at play, learning, or in tender interactions with family members. Scenes of rural labor, such as mending fishing nets or tending to farm animals, were also common, reflecting an interest in the traditional ways of life that were increasingly being impacted by industrialization. Unlike some social realist painters who focused on the harshness of poverty, Burr's depictions, while acknowledging hardship, often emphasized resilience, community, and the enduring strength of family bonds. There is a gentle sentimentality in his work, but it rarely tips into the overly saccharine, usually grounded by his honest observation.

The influence of earlier Scottish genre painters, particularly Sir David Wilkie, is palpable in Burr's work. Wilkie had established a powerful precedent for depicting scenes of Scottish life with humor, pathos, and intricate detail. Artists like John Burnet, who was also a contemporary and engraver of Wilkie's work, continued this tradition. Burr can be seen as an inheritor of this lineage, adapting it to the tastes and concerns of the mid-to-late Victorian era.

Representative Works

While a comprehensive catalogue raisonné might be extensive, several paintings exemplify John Burr's characteristic style and thematic concerns. Works often titled with descriptive phrases like Mending the Cradle, The Truant, The Village Post Office, or Bedtime give a clear indication of his focus.

One notable painting, The Peepshow (circa 1863), depicts a group of children gathered around a travelling showman's peepshow box, their faces alight with curiosity and wonder. This work captures the innocence of childhood and the simple entertainments of the era, rendered with Burr's typical attention to individual character and lively composition.

Another example, Grandfather's Favourite, would likely show a tender moment between an elderly figure and a child, a common Victorian theme emphasizing intergenerational affection and the comforts of home. Similarly, paintings depicting domestic chores, such as Preparing Dinner or Mending Clothes, would highlight the everyday labor, often of women, that sustained family life. These scenes were not merely descriptive; they often carried subtle narratives about diligence, care, and the rhythms of domesticity.

His painting A Wandering Minstrel Here, mentioned in the initial information, would fit well within his oeuvre, depicting a scene of rural entertainment and the life of itinerant performers, a subject that allowed for the portrayal of varied character types and a sense of community. The reference to "Cows Drinking" suggests his engagement with rural landscapes and animal painting, often integrated into his genre scenes or as standalone studies. While "Fish Market" was attributed to Boudin in the source, Burr certainly painted coastal and fishing-related scenes, given his Scottish heritage and the prevalence of such subjects in British art. For instance, a work titled The Bait Digger or similar would be entirely consistent with his output.

John Burr and His Contemporaries

John Burr's career unfolded during a dynamic period in British art, and his work can be understood in relation to a wide array of contemporaries, both Scottish and English.

His closest artistic relation was, of course, his brother, Alexander Hohenlohe Burr. Alexander also specialized in genre scenes, often with similar themes of domestic life and childhood. While their styles had similarities, they maintained distinct artistic identities. They exhibited together and undoubtedly influenced each other, particularly in their early careers.

Among other Scottish contemporaries, Thomas Faed (1826-1900) is a key figure. Faed was immensely popular for his sentimental and anecdotal scenes of Scottish rural life, often depicting themes of emigration, poverty, and family devotion. While Burr's work could be sentimental, it was perhaps generally less overtly dramatic than Faed's. Erskine Nicol (1825-1904), another Scottish painter, was known for his often humorous and keenly observed depictions of Irish peasant life, sharing with Burr an eye for character and everyday incidents. William McTaggart (1835-1910), though increasingly known for his impressionistic seascapes and depictions of children on the coast, also started with more detailed genre scenes, and his focus on Scottish life and childhood provides a point of comparison.

In England, the tradition of genre painting was equally strong. The artists of the Cranbrook Colony, such as Thomas Webster (1800-1886), Frederick Daniel Hardy (1827-1911), and George Bernard O'Neill (1828-1917), specialized in detailed and often charming depictions of rustic domesticity and village life. Their meticulous technique and focus on narrative vignettes share common ground with Burr's approach. William Powell Frith (1819-1909), famous for his panoramic scenes of modern Victorian life like Derby Day and The Railway Station, represented a grander scale of narrative painting, but the underlying interest in observing and recording contemporary society was a shared Victorian trait.

The influence of earlier masters like Sir David Wilkie (1785-1841) has already been noted. Wilkie's impact on subsequent generations of Scottish genre painters, including Burr, cannot be overstated. His ability to combine detailed realism with engaging storytelling set a benchmark. One might also consider the broader European context, with artists like Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) in France, whose depictions of peasant life, though often more somber and monumental, contributed to a wider 19th-century interest in rural subjects. However, Burr's work aligns more closely with the British narrative tradition.

Other notable British contemporaries whose work touched upon similar themes or styles include George Elgar Hicks (1824-1914), known for his social commentary in paintings like Woman's Mission, and Augustus Edwin Mulready (1844-1905), who often depicted London street children with a sentimental realism. The prolific illustrator and painter Myles Birket Foster (1825-1899) also created idealized images of English country life and childhood that were immensely popular.

Critical Reception, Later Life, and Legacy

During his lifetime, John Burr achieved considerable success and recognition. His paintings were popular with the public and generally well-received by critics, who appreciated his technical skill, his ability to tell a story, and the relatable nature of his subjects. His election as President of the Society of British Artists in 1881 was a significant honor, reflecting his standing in the London art world. His works were acquired by private collectors and found their way into public collections, ensuring their visibility.

He continued to paint and exhibit throughout the 1870s and 1880s, maintaining his focus on genre subjects. The demand for narrative paintings remained strong for much of the Victorian era, although by the later part of the century, new artistic movements such as Impressionism and Aestheticism were beginning to challenge traditional approaches.

John Burr passed away in London in 1893. While his name may not be as widely recognized today as some of his more famous contemporaries, his contribution to 19th-century British art is undeniable. He was a skilled and sensitive painter who captured the spirit of his age through his intimate portrayals of everyday life. His work provides valuable insight into the social customs, domestic environments, and sentimental values of the Victorian period, particularly in Scotland and rural England.

His paintings are held in various public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and numerous regional galleries throughout the United Kingdom. They continue to be appreciated for their charm, technical accomplishment, and as historical documents of a bygone era. As a chronicler of the domestic sphere and a representative of the strong Scottish tradition of genre painting, John Burr holds a secure place in the annals of British art history. His dedication to depicting the "short and simple annals of the poor," as well as the joys and sorrows of family life, ensures his enduring appeal.