John Duvall, an artist whose life spanned a significant portion of the Victorian era, carved a distinct niche for himself within the rich tapestry of British art. Active from 1816 to 1892, Duvall became particularly renowned for his sensitive and skilled depictions of animals, a genre that enjoyed immense popularity during his time. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries, his work reflects a deep understanding of animal anatomy and a genuine appreciation for his subjects, earning him respect and patronage throughout his career.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

John Duvall was born in 1816 in Ipswich, Suffolk, a county in the East of England with a surprisingly rich artistic heritage. Suffolk had previously nurtured talents like Thomas Gainsborough and John Constable, artists who, though working in different genres and eras, contributed to an environment where artistic pursuits were valued. This regional backdrop may have provided an ambient encouragement for young Duvall.

Crucially, art was a familial pursuit. John Duvall was the son of John Cantiloe Duvall (sometimes referred to as John Duvall Senior, 1790-1870), who was himself an accomplished animal painter. This paternal influence was undoubtedly the most significant factor in shaping the younger Duvall's artistic path. Growing up in an artist's household, he would have been immersed in the sights, sounds, and materials of painting from an early age. It is highly probable that his earliest training came directly from his father, learning the fundamentals of drawing, composition, and oil painting techniques, with a specific focus on capturing the likeness and spirit of animals. This direct tutelage provided a strong foundation upon which he would build his own distinct style.

A Career in Animal Painting

John Duvall dedicated his career primarily to animal portraiture and scenes of rural life. His subjects were diverse, ranging from prized livestock such as cattle, sheep, and pigs, to domestic companions like dogs, and, most notably, horses. The Victorian era saw a surge in the appreciation for animals, not just for their utilitarian purposes in agriculture and transport, but also as symbols of status, objects of affection, and subjects of scientific interest. This cultural climate provided a fertile ground for artists specializing in animal depiction.

Duvall's approach was characterized by a commitment to realism and a keen eye for detail. He possessed a remarkable ability to render the specific textures of an animal's coat, the musculature beneath, and the individual character expressed in their eyes and posture. His paintings were not mere anatomical studies; they often conveyed a sense of the animal's personality and its place within its environment, whether a stable, a farmyard, or a pastoral landscape.

His skill and dedication earned him recognition within the established art institutions of the time. John Duvall was a regular exhibitor at several prestigious venues in London. These included the Royal Academy of Arts, the premier art institution in Britain, where acceptance was a significant mark of professional achievement. He also showed his works at the British Institution and the Society of British Artists (later the Royal Society of British Artists) located on Suffolk Street. Consistent exhibition at these venues ensured his work was seen by critics, collectors, and the art-loving public, solidifying his reputation as a competent and respected animal painter.

Signature Style and Thematic Focus

Duvall's style, while rooted in the tradition of British animal painting, had its own subtle characteristics. He generally avoided the overt sentimentality or dramatic anthropomorphism that characterized the work of some of his contemporaries, such as the immensely popular Sir Edwin Landseer. Instead, Duvall's paintings often exude a quieter, more straightforward appreciation for the animals themselves. His compositions are typically well-balanced, with the animal subjects clearly being the focal point.

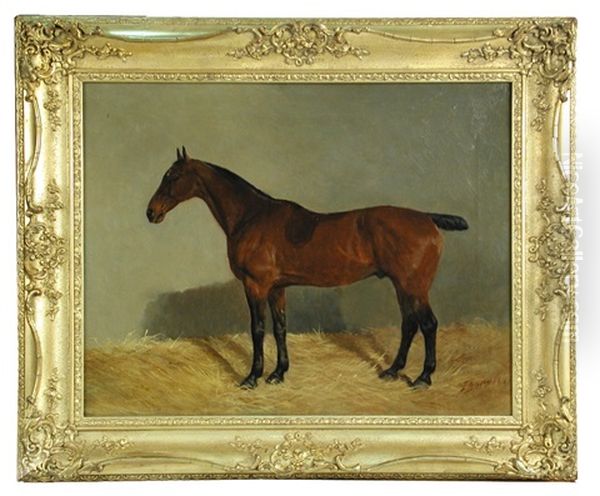

Horses were a particularly favored subject for Duvall, and he excelled in capturing their noble bearing, strength, and grace. Whether depicting a sleek hunter in a meticulously detailed stable, a sturdy cart horse at rest, or a group of horses in a field, he paid close attention to their anatomy and individual characteristics. His stable scenes, for instance, often include carefully rendered details of tack, straw bedding, and the architectural features of the building, creating a complete and convincing setting for his equine subjects.

His depictions of dogs were equally adept, capturing the alertness of terriers, the gentle nature of spaniels, or the steadfast loyalty of hounds. Farmyard scenes allowed him to bring together a variety of animals – cattle, sheep, poultry – often in harmonious, naturalistic groupings that celebrated the rhythms of rural life. These works appealed to landowners, farmers, and those who cherished the British countryside and its animal inhabitants.

Representative Works

While a comprehensive catalogue of all his works can be challenging to assemble for artists of his era who were prolific but not always exhaustively documented, several paintings exemplify John Duvall's skill and typical subject matter.

One such work, noted as having been created between 1861 and 1892, is titled A Hunter in a Stable. This painting likely showcases a prized hunting horse, meticulously rendered within the familiar setting of its stall. One can imagine the careful attention paid to the horse's glossy coat, its intelligent eye, and the details of its surroundings – perhaps a hay rack, a water bucket, and well-oiled leather tack. Such paintings were popular commissions from gentlemen who wished to have a lasting portrait of their favorite mounts.

Other titles attributed to John Duvall or typical of his oeuvre include:

Farmyard Scene with Cattle and Poultry: This type of composition would allow Duvall to display his versatility in depicting different animal forms and textures, creating a lively and authentic snapshot of agricultural life.

A Bay Hunter with a Groom: Adding a human figure, often a groom, provided a sense of scale and context, and highlighted the relationship between humans and their working animals.

Two Pointers in a Landscape: Sporting dogs were a common subject, and Duvall would have captured their characteristic poses and focused intensity.

Horses and Hounds of a Hunt: Such scenes, depicting the excitement and pageantry of the hunt, were highly sought after.

Cattle Watering in a River Landscape: These pastoral scenes combined animal painting with landscape elements, showcasing a broader range of skills.

These works, and others like them, demonstrate Duvall's consistent focus on accurate representation, his understanding of animal anatomy, and his ability to create pleasing and engaging compositions. His paintings often possess a calm, observational quality, inviting the viewer to appreciate the beauty and character of the animals depicted.

The Context of Victorian Animal Painting

To fully appreciate John Duvall's contribution, it is essential to consider the broader context of animal painting in Victorian Britain. The 19th century was a golden age for this genre. The aforementioned Sir Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) was undoubtedly the colossus of the field, his works celebrated for their technical brilliance and often imbued with narrative, moral, or sentimental themes that resonated deeply with the Victorian public. Landseer's paintings, such as "The Monarch of the Glen" or "Dignity and Impudence," became iconic.

However, the field was populated by many other talented artists. Thomas Sidney Cooper (1803-1902) was renowned for his idyllic pastoral scenes featuring cattle and sheep, often set in the Kent countryside. His meticulous rendering of these animals made him exceptionally popular and financially successful. Richard Ansdell (1815-1885) was another prominent figure, known for his sporting scenes, depictions of Spanish subjects, and dramatic animal encounters. He often collaborated with landscape painters like Thomas Creswick.

The tradition of sporting art, particularly equestrian subjects, had a long and distinguished history in Britain, with earlier masters like George Stubbs (1724-1806) setting an incredibly high standard for anatomical accuracy and artistic composition in horse painting. Stubbs's influence, though from an earlier century, still permeated the genre. Sawrey Gilpin (1733-1807) was another important predecessor in animal art.

Contemporaries or near-contemporaries of Duvall who also specialized in animal or sporting subjects included John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795-1865) and his son John Frederick Herring Jr. (1820-1907), both famous for their depictions of racehorses, coaching scenes, and farmyard animals. Abraham Cooper (1787-1868), no relation to Thomas Sidney Cooper, was a prolific painter of horses and battle scenes. James Ward (1769-1859), whose career bridged the late 18th and early 19th centuries, was known for his powerful and sometimes romanticized depictions of animals, as well as landscapes.

Other notable animal painters included William Huggins of Liverpool (1820-1884), who developed a highly detailed, almost photographic style, particularly in his depictions of lions and other exotic animals, as well as domestic livestock. Heywood Hardy (1842-1933) painted sporting scenes, animals, and 18th-century genre subjects. Later in the century, Briton Rivière (1840-1920) gained fame for his paintings that often explored the emotional connections between humans and animals, or depicted animals in dramatic or allegorical situations.

Within this vibrant and competitive artistic landscape, John Duvall established his presence. His work might be seen as occupying a space that emphasized faithful representation and a quiet appreciation for the animal subject, perhaps less theatrical than Landseer or Rivière, but deeply rooted in careful observation and skilled execution, akin in spirit to the more straightforward portrayals by artists like Thomas Sidney Cooper or the Herrings, particularly in their farmyard scenes. His connection to Suffolk also places him within a lineage of East Anglian artists who drew inspiration from their local environment, even if their subject matter varied.

Later Life and Legacy

John Duvall continued to paint throughout his life, adapting to the changing tastes and artistic trends of the Victorian era while remaining true to his core specialization. He passed away in 1892, leaving behind a substantial body of work that documents not only the animals he portrayed but also aspects of the rural life and sporting traditions of 19th-century Britain.

While he may not have achieved the same level of posthumous fame as some of his more flamboyant contemporaries, John Duvall's paintings are still appreciated today by collectors of British traditional art and by those with an interest in animal and sporting subjects. His works appear periodically at auctions, and examples can be found in regional galleries and private collections.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the rich tradition of British animal painting. He was a skilled craftsman who captured the likeness and character of his subjects with honesty and affection. His paintings serve as a visual record of the animals that were integral to the society of his time, from the working horses and farm stock to the cherished pets and sporting animals. As the son of an animal painter, he also represents a continuation of artistic skill passed down through generations, a common pattern in the history of art that often fostered specialized expertise.

In conclusion, John Duvall (1816-1892) was a dedicated and proficient British artist who excelled in the depiction of animals. Working within a popular and competitive genre, he distinguished himself through his realistic style, keen observational skills, and an evident empathy for his subjects. His paintings offer a window into the Victorian appreciation for animals and remain a testament to his skill as a master of animal portraiture. His work continues to hold appeal for its technical quality, its historical context, and the timeless charm of its animal subjects.