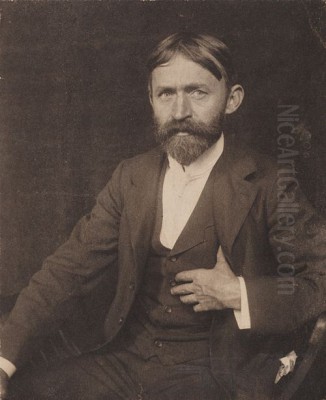

John Henry Twachtman stands as one of the most individualistic and poetic voices within the American Impressionist movement. Active during the late nineteenth century, a period of significant artistic transformation both in Europe and the United States, Twachtman developed a style characterized by its subtlety, atmospheric depth, and experimental nature. While influenced by European trends, particularly French Impressionism and the Tonalism associated with James McNeill Whistler, Twachtman forged a path uniquely his own, focusing intensely on the landscapes that surrounded him, particularly his farm in Greenwich, Connecticut. Though not achieving widespread fame during his relatively short lifetime, his work has since been recognized for its profound sensitivity and its quiet anticipation of modernist abstraction. He was a key figure in the formation of "The Ten American Painters," a group that championed artistic freedom and newer aesthetic ideals.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

John Henry Twachtman was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on August 4, 1853. His parents were German immigrants, and his father, Frederick Christian Twachtman, worked as a window shade decorator. This early exposure to decorative arts may have subtly influenced young John's aesthetic sensibilities. Cincinnati at the time was a burgeoning cultural center in the American Midwest, possessing a growing arts scene. Twachtman showed an early aptitude for drawing and painting, initially pursuing work similar to his father's, decorating window shades by the age of fourteen.

His formal art education began locally at the McMicken School of Design (later the Art Academy of Cincinnati). A pivotal moment came when he met Frank Duveneck, a charismatic Cincinnati-born artist who had recently returned from studying at the Royal Academy in Munich. Duveneck became a significant mentor, and Twachtman enrolled in Duveneck's classes at the Ohio Mechanics Institute. Duveneck's style, heavily influenced by the Munich School's dark palette, vigorous brushwork, and realist tendencies inspired by artists like Wilhelm Leibl, profoundly shaped Twachtman's early work.

European Sojourns and Stylistic Shifts

In 1875, Twachtman accompanied Duveneck and fellow Cincinnati artist Henry Farny to Europe, enrolling at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. There, he studied under Ludwig von Löfftz, further immersing himself in the prevailing Munich style. This approach emphasized bravura brushwork, rich, dark tones, and often dramatic chiaroscuro, drawing inspiration from Old Masters like Frans Hals and Diego Velázquez. Twachtman quickly absorbed these lessons, producing works characterized by their painterly energy and somber palettes. His paintings from this period often depicted figures or cityscapes rendered with confident, visible strokes.

Following his Munich studies, Twachtman traveled with Duveneck and William Merritt Chase to Venice in 1877. The unique light and atmosphere of Venice began to subtly alter his approach. He started experimenting with etching, a medium that encouraged simplification and attention to line and tone. While his palette remained relatively subdued compared to his later work, the Venetian experience marked the beginning of a gradual shift towards a greater sensitivity to light and atmosphere, moving away from the heavier impasto and darker tones of the Munich School.

A second significant European period began in 1883 when Twachtman moved to Paris with his wife, Martha Scudder, whom he had married in 1881. He enrolled at the Académie Julian, studying under Gustave Boulanger and Jules Lefebvre. Paris was the epicenter of Impressionism, and Twachtman inevitably absorbed the influences of artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro. He began to lighten his palette considerably, adopting softer colors and exploring the effects of light more directly. His brushwork became more delicate, sometimes employing broken color, though he rarely adopted the full spectrum or the systematic application of color theory seen in core French Impressionism. This period marked a decisive turn towards landscape painting and a more personal, lyrical interpretation of nature.

Return to America and the Greenwich Years

After his studies in Paris and a brief period working on a farm in Holland with his friend J. Alden Weir, Twachtman returned to the United States around 1886. Seeking a place conducive to his evolving artistic focus on landscape, he eventually purchased a seventeen-acre farm near Greenwich, Connecticut, in 1889. This property, with its farmhouse, barn, brook (Horseneck Brook), waterfall, and hemlock-shaded pool, became the central motif and inspiration for the most celebrated phase of his career. Unlike the bustling art colonies forming elsewhere, Twachtman's Greenwich home offered a degree of seclusion, allowing for intense, sustained observation of his immediate surroundings throughout the changing seasons.

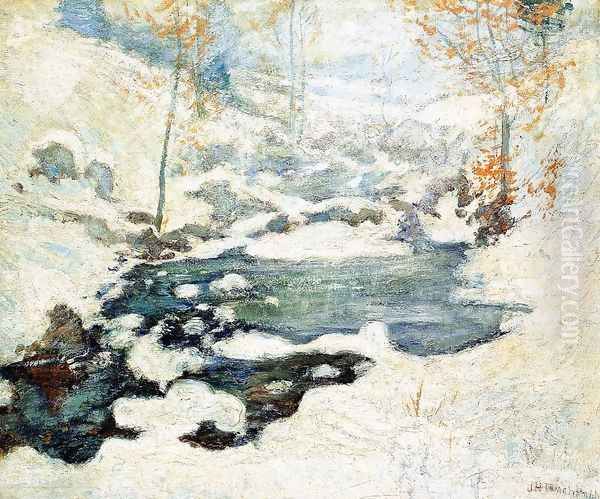

The Greenwich landscape dominated his output for over a decade. He painted his house, his garden, the brook in various states – flowing freely, frozen, or snow-covered – the waterfall, and the quiet pool under the hemlocks. This intimate connection to a specific place allowed him to explore subtle variations in light, color, and atmosphere with remarkable sensitivity. His paintings from this period are often characterized by a sense of quiet contemplation and a deep, personal connection to the land. He became a master of depicting snow scenes, capturing the hushed beauty and delicate tonal variations of winter landscapes.

The Development of a Unique Style

Twachtman's mature style represents a unique synthesis of diverse influences, refined through his personal vision. While clearly impacted by French Impressionism in its attention to light, atmosphere, and often looser brushwork, his work retained a distinct character. He rarely employed the vibrant, high-key palette typical of Monet or Renoir. Instead, he favored subtle harmonies, often working within a limited range of closely related tones, frequently dominated by soft grays, greens, blues, and violets. This aspect connects his work to Tonalism, an American movement inspired partly by the atmospheric works of James McNeill Whistler and George Inness, which emphasized mood, spirituality, and evocative color harmonies over precise depiction.

Another crucial influence was Japonisme – the European and American fascination with Japanese art, particularly Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. Like Whistler and Edgar Degas, Twachtman admired the flattened perspectives, asymmetrical compositions, decorative patterns, and emphasis on line found in Japanese prints. This influence is evident in the high horizons, simplified forms, and sometimes abstract patterning seen in his compositions, such as the series depicting the waterfall on his property or the paintings of his hemlock pool. He often tilted the picture plane upwards, minimizing traditional perspective and focusing on the surface design.

His technique was also experimental. He varied his paint application considerably, sometimes using thin washes that soaked into the canvas, other times building up delicate layers of texture, and occasionally employing thicker impasto for specific effects. This technical versatility allowed him to capture the specific textures and moods of different seasons and weather conditions, from the delicate tracery of bare branches against a winter sky to the shimmering reflections on water in summer. His approach was less about objective recording and more about conveying a subjective, emotional response to nature.

Analysis of Key Works

Twachtman's oeuvre includes numerous masterpieces that exemplify his unique style. Arques-la-Bataille (c. 1885), painted during his French period, shows the transition towards Impressionism. While still retaining some tonal subtlety, the palette is lighter than his Munich work, and the brushwork captures the shimmering quality of light on water and foliage. It demonstrates his growing interest in landscape and atmospheric effects, influenced by his time near Dieppe.

The paintings created at his Greenwich farm represent the core of his achievement. Works like Winter Harmony (c. 1890-1900) and Icebound (c. 1889) are iconic examples of his snow scenes. Winter Harmony features a delicate interplay of whites, grays, and pale blues, capturing the stillness and subtle light of a snow-covered landscape with exquisite sensitivity. The composition is simplified, focusing on the gentle curves of the snowdrifts and the filigree of bare trees. Icebound depicts Horseneck Brook frozen over, using textured brushwork to convey the rough surface of the ice and snow, while maintaining an overall atmospheric unity.

The White Bridge (c. 1895) is another signature Greenwich work. Depicting a simple wooden bridge arching over the brook on his property, the painting is rendered in soft, high-key tones, predominantly whites, pale greens, and blues. The composition, potentially influenced by Japanese prints or Monet's paintings of his own Japanese bridge at Giverny, features flattened space and decorative elements. The painting evokes a sense of tranquility and idyllic beauty, a recurring theme in his depictions of his farm.

The Hemlock Pool series, including Hemlock Pool (Autumn) (c. 1900), explores another favorite motif on his property. These works often feature reflections in the still water, surrounded by the dark forms of the hemlock trees. The compositions can be quite abstract, focusing on the interplay of light, shadow, and reflection, reducing the natural forms to patterns of color and tone. These paintings demonstrate his move towards a more subjective and abstracted vision of nature in his later years.

The Yellowstone Expedition

A notable departure from his usual subject matter occurred in 1895 when Twachtman traveled west to Yellowstone National Park. He was commissioned, along with his friend J. Alden Weir, by Major W. A. Wadsworth of Geneseo, New York, a significant art patron. This trip provided Twachtman with dramatically different scenery – geysers, hot springs, waterfalls, and canyons. He produced a small number of works based on this trip, including paintings of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone and various thermal features like Morning Glory Pool and Emerald Pool.

These Yellowstone paintings often display a brighter palette and bolder handling than his typical Connecticut landscapes, responding to the intense colors and grand scale of the western environment. However, the trip was reportedly challenging; the artists encountered difficult weather, including an early blizzard, which may have limited their output. While an interesting interlude, the Yellowstone works remain somewhat distinct from the main trajectory of his artistic development, which remained deeply rooted in the more intimate landscapes of the Northeast.

The Ten American Painters

Twachtman played a crucial role in the formation of "The Ten American Painters" (often referred to simply as "The Ten") in 1897. This group represented a secession from the larger, more conservative Society of American Artists (SAA). The founding members felt that the SAA's large annual exhibitions had become too commercialized and aesthetically uneven, hindering the display of more progressive or stylistically coherent work. They sought smaller, more harmonious exhibitions where their paintings, often Impressionist or Tonalist in style, could be shown to better advantage.

Besides Twachtman, the original members of The Ten were Childe Hassam, J. Alden Weir, Thomas Dewing, Joseph DeCamp, Frank W. Benson, Edmund C. Tarbell, Robert Reid, Edward Simmons, and Willard Metcalf. (After Twachtman's death, William Merritt Chase took his place). The group exhibited together annually from 1898 until 1919. Twachtman's participation underscored his commitment to artistic independence and his alignment with the more forward-looking trends in American art at the turn of the century. His own highly personal and experimental style embodied the spirit of individualism that The Ten sought to promote.

Teaching and Influence

Beyond his own painting, Twachtman was also a respected teacher. From 1889 until his death, he taught painting at the Art Students League in New York. He also taught at the Cooper Union School of Design for Women. His teaching methods were reportedly unconventional for the time, encouraging students to develop their own individual responses to nature rather than adhering strictly to academic formulas. He emphasized observation, feeling, and the expressive potential of paint itself.

His gentle demeanor and insightful critiques made him a popular instructor. While his direct influence is difficult to trace definitively to specific famous artists, his presence at these important institutions undoubtedly impacted a generation of younger painters. His emphasis on personal vision and experimentation likely resonated with students seeking alternatives to traditional academic training. His dedication to teaching also provided a necessary source of income, as his own paintings, while admired by fellow artists and discerning critics, did not sell readily during his lifetime.

Late Works and Abstraction

In the final years of his life, starting around 1900, Twachtman began spending summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts, a popular destination for artists drawn to its picturesque harbor and coastal scenery. His Gloucester paintings mark another stylistic evolution, often characterized by bolder compositions, stronger color contrasts, and a more vigorous, sometimes almost abstract, handling of paint. Works like Fishing Boats at Gloucester (c. 1901) display a heightened sense of structure and a simplification of forms that pushes further towards abstraction than much of his earlier work.

These late paintings suggest Twachtman was continuing to experiment and evolve right up until his untimely death. They demonstrate a move away from the delicate atmospheric effects of his Greenwich period towards a more direct, forceful engagement with the subject. Some art historians see in these late works a prefiguration of early twentieth-century American modernism, particularly in their emphasis on formal structure and expressive brushwork. His exploration of near-abstract compositions, particularly in the Hemlock Pool and late Gloucester works, places him as a transitional figure, rooted in Impressionism but looking towards future developments.

Legacy and Posthumous Recognition

John Henry Twachtman died suddenly of a brain aneurysm while vacationing in Gloucester on August 8, 1902, just four days after his forty-ninth birthday. His death cut short a career that was still very much in development. During his lifetime, he was highly respected by fellow artists like Weir, Hassam, and Theodore Robinson, but his work was often considered too subtle or "unfinished" by the broader public and many critics accustomed to more traditional styles. Consequently, he achieved limited financial success or widespread fame.

However, in the decades following his death, his reputation grew steadily. Posthumous exhibitions, including a memorial exhibition organized by The Ten, helped bring his work to greater attention. Critics and art historians began to recognize the unique quality of his vision – its poetic sensitivity, its technical mastery, and its quiet originality. He came to be seen not just as an American Impressionist, but as one of the most innovative and forward-looking artists of his generation. His ability to infuse landscapes with deep personal feeling and his willingness to experiment with form and technique set him apart.

Today, John Henry Twachtman is considered a major figure in American art history. His paintings are held in the collections of leading museums across the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Cincinnati Art Museum. His works, particularly the snow scenes and depictions of his Greenwich farm, are celebrated for their ethereal beauty and profound connection to nature. His legacy lies in his creation of a deeply personal and evocative form of landscape painting that bridged the gap between nineteenth-century Impressionism and the emerging aesthetics of the twentieth century.

Conclusion

John Henry Twachtman's artistic journey took him from the dark realism of the Munich School through the light-filled discoveries of French Impressionism to a highly personalized style that blended atmospheric subtlety with structural experimentation. His deep engagement with the landscape of his Connecticut farm produced a body of work remarkable for its poetic depth and nuanced observation. As a founding member of The Ten American Painters and an influential teacher, he played a significant role in the evolution of American art at the turn of the century. Though his life was short and fame elusive during his time, John Henry Twachtman's quiet, contemplative, and innovative paintings have secured his place as one of America's most important and beloved landscape painters, an artist whose vision continues to resonate with viewers today.