Sir John Watson Gordon stands as one of Scotland's most distinguished portrait painters of the 19th century. His career, spanning a period of significant artistic and social change, saw him rise from a young man with an uncertain path to become the President of the Royal Scottish Academy and Queen Victoria's Limner in Scotland. His legacy is built upon a foundation of astute character observation, technical skill, and a dedication to the art of portraiture that captured the likenesses of many of his era's most notable figures.

Early Life and a Fateful Turn to Art

Born John Watson in Edinburgh in 1788, he was the eldest son of Captain James Watson of the Royal Navy, a man of respectable standing. His early education was geared towards a career in the military, specifically with the Royal Engineers or the Navy. However, fate, and perhaps a burgeoning artistic inclination, intervened. While attending the Trustees' Academy in Edinburgh, a venerable institution for artistic training, he came under the tutelage of John Graham. It was here, amidst the casts and canvases, that he encountered a fellow student who would profoundly influence his path: David Wilkie.

Wilkie, who would later achieve international fame for his genre paintings, recognized Watson's talent and encouraged him to pursue art as a profession. This encouragement, coupled with Watson's own developing passion, led him to abandon his military aspirations and dedicate himself to painting. His formal training was also supplemented by studies at the Government School of Design, which was managed by the Board of Manufactures, further grounding him in the principles of art. His family background was not entirely removed from the arts; his uncle, George Watson, was already an established painter and would later serve as the first President of the Royal Scottish Academy, providing a familial link to the profession.

The Shadow and Light of Raeburn

John Watson began his exhibiting career in 1808, with one of his early notable works being "The Lay of the Last Minstrel," inspired by Sir Walter Scott's popular poem. In these early years, the dominant figure in Scottish portraiture was Sir Henry Raeburn. Raeburn, a family friend of the Watsons, cast a long and influential shadow over the Edinburgh art scene. His bold, direct style, characterized by strong chiaroscuro and an ability to capture the essential character of his sitters, set a high standard.

Naturally, Watson's initial works bore the imprint of Raeburn's style. He admired Raeburn's technique and his ability to convey personality with such apparent ease. For any aspiring portraitist in Edinburgh at the time, Raeburn was the benchmark. However, Watson was not content to remain merely an imitator. While he learned much from Raeburn's example, he gradually began to forge his own artistic identity. The death of Raeburn in 1823 created a void in Scottish portraiture, and it was into this space that John Watson, among others, stepped forward.

In 1826, to distinguish himself from his uncle George Watson and his cousin William Smellie Watson, also painters, he adopted the additional surname Gordon. This decision marked a step towards establishing his unique professional identity as Sir John Watson Gordon. He began to inherit much of Raeburn's practice, becoming the go-to artist for many of Scotland's elite seeking to have their likenesses preserved.

Forging a Distinctive Style

While his early works were described as having a certain sweetness and richness of colour, Watson Gordon's style evolved significantly throughout his career. He moved towards a more restrained and sober palette, often favoring strong, clear drawing and a meticulous attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of his sitters' features and attire. His approach became increasingly characterized by a keen, almost forensic, observation.

A significant influence on his mature style, beyond Raeburn, is said to have been the Spanish master Diego Velázquez. Watson Gordon admired Velázquez's realism, his psychological penetration, and his masterful handling of paint. This influence can be seen in the solidity of his figures, the dignified portrayal of his subjects, and the subtle gradations of tone that define form. He developed a reputation for producing portraits that were not only accurate likenesses but also conveyed a strong sense of the sitter's character and intellect.

His later works, in particular, were praised for their "transparent flesh tints" and "highly finished" technique. While some critics occasionally noted that his work might lack the ultimate "force and individuality of a master" when compared to the very greatest portraitists in history, his skill in capturing a truthful and insightful representation was widely acknowledged. He excelled in portraying men of substance – academics, lawyers, clergymen, and civic leaders – investing them with an air of gravity and intelligence.

A Prolific Portraitist of His Era

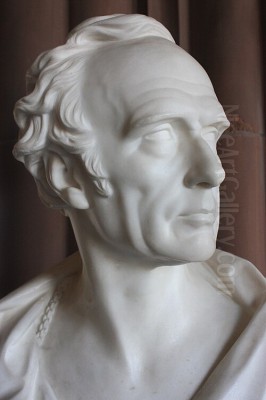

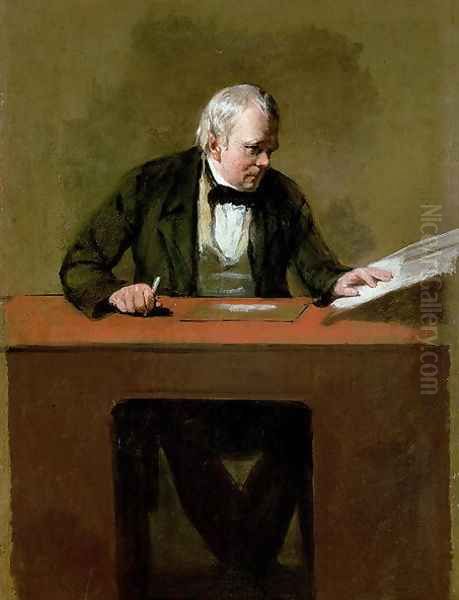

Sir John Watson Gordon was exceptionally prolific. His studio was a hub for the prominent figures of Scottish society. Among his most celebrated sitters was the literary giant Sir Walter Scott. His portrait of Scott, painted around 1830 and now in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, is considered one of the definitive images of the author, capturing his thoughtful and humane expression.

He also painted Scott's son-in-law and biographer, John Gibson Lockhart, and the essayist Thomas De Quincey, famous for "Confessions of an English Opium-Eater." These literary portraits demonstrate his ability to engage with the intellectual and creative personalities of his time. His sitters also included numerous military figures, such as General Sir Alexander Hope and Admiral Lord Charles Malcolm, reflecting his father's naval background and the importance of the military in British society.

Civic and academic leaders frequently sat for him. Portraits like that of Sir James Hall, former President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, and Dr. Thomas Chalmers, a leading figure in the Church of Scotland, showcase his capacity to depict authority and intellect. Other notable portraits include those of Sir Archibald Alison, the historian, Sir John Shaw Lefevre, a public servant and academic, David Roberts (likely the renowned topographical painter, often initialed D.R.H.B.S.A.), John Whiteford Mackenzie (housed in the Signet Library), William Brodie, 23rd Laird of Brodie (National Trust for Scotland), and Alexander Mcleish (Glasgow Museums Resource Centre). Each portrait aimed to be a faithful record, imbued with a sense of the individual's presence and social standing.

The Royal Scottish Academy and National Acclaim

John Watson Gordon was deeply involved in the institutional art life of Scotland. He was one of the earliest members of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA), an institution founded in 1826 to promote contemporary Scottish art and provide an alternative to exhibiting in London. The RSA quickly became the focal point for artists in Scotland, offering exhibition opportunities, training, and a sense of collective identity.

His dedication and standing within the artistic community led to his election as President of the Royal Scottish Academy in 1850, succeeding Sir William Allan. This was a significant honour, placing him at the helm of Scotland's premier art institution. In the same year, his eminence was further recognized when he was appointed Her Majesty's Limner for Scotland, a prestigious royal appointment. Shortly thereafter, in 1850, he was knighted by Queen Victoria, becoming Sir John Watson Gordon.

His connection to the London art establishment was also strong. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in London in 1841, and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1851. These accolades cemented his reputation not just within Scotland, but across Britain as a leading portrait painter of his generation. His tenure as President of the RSA lasted until his death, a period during which he guided the Academy with a steady hand.

Notable Works and Their Enduring Qualities

Beyond the sheer number of his portraits, several stand out for their artistic merit and historical significance. "The Lay of the Last Minstrel" (1808), his early subject picture, demonstrated his ambition and engagement with contemporary literary themes, a common practice among artists like Benjamin West or Henry Fuseli who drew from literature and history.

His portrait of Sir Walter Scott (c. 1830) remains a cornerstone of his oeuvre. It is a work of quiet dignity, capturing Scott in his later years with a sympathetic and insightful gaze. The handling of the face, the thoughtful eyes, and the slightly melancholic expression speak volumes about the sitter. This contrasts with the more heroic or romanticized depictions by other artists like Sir Thomas Lawrence or Sir Henry Raeburn himself.

The portrait of "A Grandfather" (also known as "The Provost") is another fine example of his mature style, showcasing his ability to convey character through subtle means. The firm set of the jaw, the direct gaze, and the carefully rendered details of age and attire create a powerful impression of a man of authority and experience. Similarly, his portrait of "David Brewster," the eminent scientist and inventor, captures the intellectual intensity of the subject.

His female portraits, though perhaps less numerous or less frequently highlighted than his male subjects, also demonstrate his skill. He could capture elegance and refinement, though his strength lay more in conveying character than in flattering idealization, a trait he shared with Thomas Eakins in a later American context. His works generally avoided the flamboyant theatricality seen in some of Lawrence's portraits or the sentimentalism that could creep into Victorian art.

Contemporaries and the Scottish Art Scene

The Scottish art scene during Watson Gordon's lifetime was rich and varied. While he specialized in portraiture, other artists excelled in different genres. David Wilkie, his early mentor, achieved international renown for his detailed and anecdotal genre scenes, influencing a generation of painters. Alexander Nasmyth was a key figure in Scottish landscape painting, and also a portraitist and teacher. His son, Patrick Nasmyth, continued this landscape tradition.

In portraiture, Andrew Geddes was a significant contemporary, known for his sensitive characterizations and rich, Rembrandtesque use of light and shadow. John Graham-Gilbert was another respected portrait painter active in Scotland. Later in Watson Gordon's career, artists like Sir Daniel Macnee and Sir Francis Grant (who became President of the Royal Academy in London) continued the strong tradition of Scottish portraiture. Sir George Harvey, who would succeed Watson Gordon as President of the RSA, was known for his historical and genre scenes, often with Scottish themes.

The influence of earlier Scottish masters like Allan Ramsay, who had brought a refined Rococo elegance to British portraiture in the 18th century, still resonated. The broader British art world included giants of landscape like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable, whose innovations were transforming that genre. In London, portraiture had been dominated by Sir Thomas Lawrence until his death in 1830, followed by figures like Martin Archer Shee. Watson Gordon's career unfolded against this dynamic backdrop, and he carved out a distinct and respected place for himself, primarily within the Scottish context but with recognition extending beyond.

Later Years and Lasting Legacy

Sir John Watson Gordon continued to paint actively into his later years, his skill and reputation undiminished. He remained a central figure in the Edinburgh art world, respected for his artistic achievements and his leadership of the Royal Scottish Academy. His dedication to his craft was unwavering, and he maintained a high standard of quality throughout his long career.

He passed away in Edinburgh on June 1, 1864, at the age of 76. His death was mourned by the artistic community and by the many individuals whose likenesses he had so skillfully captured. He left behind a vast body of work, a visual record of the prominent men and women of his time, particularly those who shaped Scottish society in the first half of the 19th century.

His legacy is that of a consummate professional, a painter who understood the demands of portraiture – the need for a good likeness, the conveyance of character, and the creation of a lasting artistic statement. His works are found in major collections, including the National Galleries of Scotland, the Royal Collection, and numerous private and civic collections. He successfully navigated the transition from the era of Raeburn to the mid-Victorian period, adapting his style while retaining his core commitment to truthful and dignified representation.

Critical Reception and Historical Standing

Throughout his career, John Watson Gordon enjoyed considerable critical acclaim and public esteem. His election to the presidencies and academician roles he held are testament to the high regard in which he was held by his peers. His portraits were generally praised for their strong likenesses, their solid craftsmanship, and their insightful characterization. He was seen as a worthy successor to Raeburn, upholding the tradition of strong Scottish portraiture.

While he may not have possessed the dazzling bravura of a Lawrence or the profound psychological depth of a Rembrandt, his strengths were considerable. He offered a sober, intelligent, and often penetrating view of his sitters. His work avoided excessive flattery or sentimentality, characteristics that could mar lesser Victorian portraiture. Instead, he focused on the essential dignity and individuality of his subjects.

In the annals of British art, Sir John Watson Gordon holds a secure and honorable place. He is a key figure in the story of Scottish art, representing a period of flourishing talent and institutional growth. His portraits provide an invaluable historical record, offering insights into the personalities and appearances of the figures who shaped 19th-century Scotland. For students of portraiture and Scottish art history, his work remains a subject of study and appreciation, a testament to a long and distinguished career dedicated to capturing the human face and spirit. His influence can be seen in the subsequent generation of Scottish portraitists, who built upon the solid foundations he helped to lay.