Joseph Ducreux stands as a fascinating and somewhat unconventional figure in the landscape of 18th-century European art. A French artist of considerable talent and versatility, he navigated the tumultuous period from the height of the Ancien Régime through the French Revolution and into the Napoleonic era. Primarily celebrated for his insightful portraits and, most notably, his strikingly expressive self-portraits, Ducreux's work offers a unique window into the era's evolving understanding of individuality and emotion. His career saw him serve royalty, adapt to revolutionary upheaval, and ultimately leave a legacy that continues to intrigue and amuse audiences today, partly due to the unexpected modern revival of his imagery in internet culture.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Joseph Ducreux was born on June 26, 1735, in Nancy, located in the Lorraine region of France, which at the time was an independent duchy soon to be incorporated into France. His father was also a painter, providing an early artistic environment. Seeking broader opportunities and more advanced training, Ducreux moved to Paris in 1760. This was a pivotal decision, placing him at the heart of the European art world.

In Paris, Ducreux sought out the tutelage of one of the most esteemed pastel portraitists of the era, Maurice Quentin de La Tour. La Tour was renowned for his psychologically astute and vibrant pastel portraits, capturing the likenesses of Enlightenment figures and French nobility with remarkable vivacity. Under La Tour's guidance, Ducreux honed his skills in pastel, a medium that allows for a directness and immediacy well-suited to capturing fleeting expressions and the subtleties of character. The influence of La Tour's emphasis on capturing the inner life of his sitters is evident throughout Ducreux's career.

Beyond La Tour, Ducreux was also significantly influenced by the work of Jean-Baptiste Greuze. Greuze was a prominent painter known for his sentimental genre scenes and his expressive, often dramatic, portraits that aimed to convey moral lessons or intense emotional states. Greuze's interest in depicting strong emotions and character, sometimes bordering on the theatrical, resonated with Ducreux's own developing fascination with physiognomy – the study of facial features and expressions to discern character and temperament. This interest would become a hallmark of Ducreux's most distinctive works.

Ascent in the Royal Court

Ducreux's talent did not go unnoticed. His skill as a portraitist, particularly his ability to capture a lively and engaging likeness, brought him to the attention of the French royal court. A significant turning point in his career occurred in 1769. He was dispatched to Vienna by King Louis XV on a prestigious and delicate mission: to paint a miniature portrait of the Archduchess Maria Antonia of Austria, who was soon to marry the Dauphin, the future Louis XVI, and become Queen Marie Antoinette of France. This portrait was crucial, as it would be one of the first likenesses of the future queen seen by the French court.

His work in Vienna was evidently successful and well-received. Not only did he complete the commission to satisfaction, but his talents also impressed the Austrian court. For his services and artistic merit, Maria Theresa, the Holy Roman Empress and Maria Antonia's mother, is said to have granted him the title of baron. Furthermore, upon Marie Antoinette's arrival in France and her marriage to Louis XVI, Ducreux's connection with her continued. He was appointed premier peintre de la reine (First Painter to the Queen), a prestigious title that solidified his position within the court's artistic circles. This role provided him with numerous commissions to paint Marie Antoinette and other members of the aristocracy. His Portrait of Marie Antoinette from this period (circa 1769) is a key example of his official work, demonstrating his skill in formal portraiture, though perhaps with less of the overt expressiveness that would characterize his later self-portraits.

As a court painter, Ducreux would have been aware of other artists vying for royal patronage, such as Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, both highly successful female portraitists who also famously painted Marie Antoinette. While Vigée Le Brun's portraits of the Queen often emphasized elegance and maternal grace, Ducreux's approach, even in formal commissions, sought a certain directness.

The Fascination with Physiognomy and Expressive Self-Portraits

While Ducreux fulfilled his duties as a court portraitist, his most personal and arguably most innovative works were his series of self-portraits. In these, he moved beyond the conventions of formal portraiture to explore a wide range of human emotions and expressions. This interest was deeply connected to the burgeoning 18th-century fascination with physiognomy, most famously popularized by the Swiss pastor and writer Johann Kaspar Lavater, whose "Essays on Physiognomy" (published from the 1770s) gained immense popularity across Europe. Lavater's theories suggested that character could be read from a person's facial features and expressions.

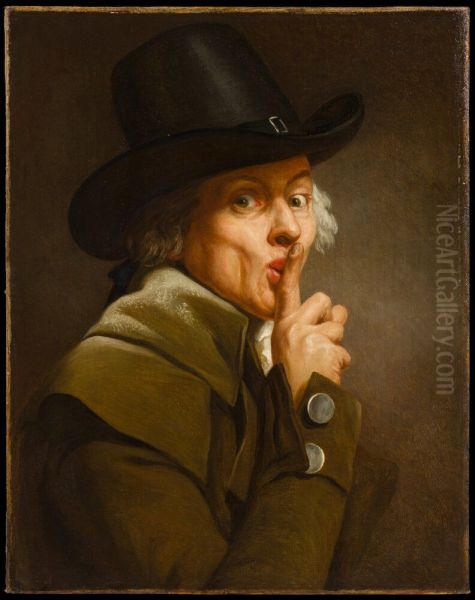

Ducreux took this interest to a highly personal and artistic level. He produced a series of self-portraits in various states of emotion: yawning, laughing, surprised, silent, mocking, and even in a state of terror or shock. These were not merely academic studies; they were bold, often humorous, and highly unconventional explorations of the self. Works like Self-Portrait, Yawning (c. 1783, Getty Museum), Self-Portrait in the Guise of a Mocker (Le Moqueur, c. 1791, Louvre), Surprise and Terror (c. 1790s), and Silence (Le Discret) showcase his willingness to break from the dignified and often idealized representations typical of self-portraiture at the time.

In Self-Portrait, Yawning, he captures the unglamorous, everyday act with remarkable naturalism and a touch of humor, his mouth wide, eyes crinkling. In Le Moqueur, he points directly at the viewer with a knowing, almost conspiratorial smirk, engaging the audience in a playful and direct manner. These works demonstrate a keen observation of his own features and an ability to translate fleeting expressions into lasting images. His use of dynamic poses, direct gazes, and exaggerated (yet believable) expressions set these works apart. They reveal an artist keenly interested in the new Enlightenment emphasis on individual feeling and authentic self-expression, pushing the boundaries of portraiture.

This exploration of extreme facial expressions finds some parallel in the "character heads" (Karakterköpfe) of the Austrian sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt, who was active in Vienna around the time Ducreux visited. While it's not definitively documented that they met, the shared interest in exaggerated physiognomic studies is notable, suggesting a broader cultural current. Messerschmidt's sculpted heads, depicting a range of often grotesque grimaces, were also attempts to systematically categorize human expressions, albeit with a more intense and perhaps psychologically troubled edge than Ducreux's often more playful approach.

Versatility in Media: Pastels, Miniatures, and Engravings

Joseph Ducreux was not limited to oil painting. His training with La Tour had made him an adept pastellist. Pastels, with their powdery consistency, allow for soft transitions, vibrant colors, and a speed of execution that can capture the immediacy of an expression. Many of his portraits, including some self-portraits, were executed in this medium, showcasing a delicate touch and a rich understanding of color.

He was also a skilled miniaturist, as evidenced by his crucial commission to paint Maria Antonia in Vienna. Miniature painting required meticulous precision and the ability to capture a likeness on a very small scale, often for personal keepsakes or diplomatic gifts. This skill demonstrated his versatility and attention to detail.

Furthermore, Ducreux was an engraver. He produced engravings after his own paintings and those of others. This was an important way for artists to disseminate their work to a wider audience before the advent of photography. His engravings, like his paintings, often focused on character and expression. This multifaceted skill set – painter in oils and pastels, miniaturist, and engraver – allowed him to navigate different sectors of the art market and cater to varied demands.

Navigating the French Revolution

The French Revolution, beginning in 1789, brought profound upheaval to French society and to the lives of those associated with the Ancien Régime. As premier peintre de la reine, Ducreux's position was precarious. His close ties to Marie Antoinette and the aristocracy made him a potential target for revolutionary fervor.

In 1791, Ducreux made the prudent decision to leave Paris and travel to London. During his time in London, he continued to paint and exhibit. He showed his expressive self-portraits at the Royal Academy of Arts, where they would have been seen by a British public accustomed to the grand manner portraiture of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough, and the emerging talents of Sir Thomas Lawrence. While in London, he also painted portraits of prominent figures, adapting his style to the tastes of his new clientele. This period of exile allowed him to continue his artistic practice away from the immediate dangers of the Terror in France.

However, Ducreux did not remain in London permanently. By 1793, as the political situation in France continued to evolve, he returned to Paris. This was a bold move, as the Reign of Terror was still a dangerous period. Upon his return, he managed to re-establish his career. It is said that he received assistance from the powerful revolutionary artist Jacques-Louis David. David, a leading figure in the Neoclassical movement and an influential member of the revolutionary government's arts committees, played a significant role in shaping the artistic landscape of the new French Republic. A connection with David would have been invaluable for an artist like Ducreux, who was trying to navigate the changed political and cultural climate.

During this later phase of his career, Ducreux continued to paint portraits, including some of the figures of the Revolution, such as Maximilien Robespierre and Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, though the attributions of some of these can be debated. He also continued with his characteristic expressive self-portraits, adapting his unique style to the new era.

Artistic Circle and Contemporary Context

Throughout his career, Ducreux operated within a rich and diverse artistic milieu. His teacher, Maurice Quentin de La Tour, was a dominant figure in pastel portraiture, whose sitters included Voltaire and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, another key influence, enjoyed immense popularity for his moralizing genre scenes and expressive portraits, influencing artists like Jean-Honoré Fragonard in his "fantasy figures" which also emphasized expressive qualities.

In the realm of court portraiture, Ducreux was a contemporary of Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard, both of whom achieved remarkable success and membership in the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, an institution Ducreux himself never formally joined, preferring a more independent path, sometimes exhibiting at alternative venues like the Salon de la Correspondance.

The sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon was another major contemporary, renowned for his lifelike busts of Enlightenment figures and American statesmen, sharing with Ducreux an interest in capturing the true character and vitality of his subjects. The art world of Paris also included landscape painters like Hubert Robert, famous for his picturesque ruins, and Joseph Vernet, celebrated for his dramatic seascapes.

During his London sojourn, Ducreux would have been aware of the towering figures of British portraiture: Sir Joshua Reynolds, the first president of the Royal Academy, known for his "Grand Manner" portraits; Thomas Gainsborough, Reynolds's great rival, celebrated for his fluid brushwork and sensitive portrayals; and George Romney, another popular society portraitist. The younger generation, including Sir Thomas Lawrence, was also beginning to make its mark with a more dramatic and romantic flair. While direct interactions are not extensively documented, Ducreux's work would have been seen in the context of these British masters.

His later association with Jacques-Louis David places him in the orbit of the leading proponent of Neoclassicism, a style that emphasized clarity, order, and civic virtue, often contrasting with the more flamboyant or sentimental aspects of Rococo and pre-revolutionary art. David's studio was a training ground for many prominent artists of the next generation, such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Antoine-Jean Gros.

Other notable European artists of the period whose work might offer points of comparison or contrast include the Swiss-born Angelica Kauffman, a prominent Neoclassical history painter and portraitist active in London and Rome, and the Spanish master Francisco Goya, whose own explorations of human psychology and expressive portraiture, particularly in his later career, would take on a darker, more critical tone.

Legacy and Modern Rediscovery

Joseph Ducreux died on July 24, 1802, in Paris, reportedly from a stroke while walking from Paris to Saint-Denis. For many years after his death, he remained a relatively niche figure in art history, appreciated by connoisseurs for his skill but not widely known to the general public. His official portraits were seen as competent examples of late Rococo court art, while his expressive self-portraits were considered curiosities.

However, in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, Ducreux experienced an unexpected and remarkable resurgence in popularity, largely thanks to the internet. His Self-Portrait in the Guise of a Mocker (pointing at the viewer) became the basis for a popular internet meme. Typically, the meme superimposes archaic, overly formal English translations of modern slang or rap lyrics onto the image, creating a humorous juxtaposition between the 18th-century artwork and contemporary language. Other self-portraits, like the yawning one, have also found their way into online culture.

While this memeification might seem a frivolous afterlife for a serious artist, it has undeniably brought Ducreux's name and, more importantly, his imagery to a vast global audience that might otherwise never have encountered his work. It has sparked curiosity about the artist and his intentions, leading many to discover the genuine artistic merit and historical interest of his oeuvre.

Beyond the internet phenomenon, Ducreux's work holds a legitimate place in the history of art. His self-portraits, in particular, are significant for their early and bold exploration of physiognomy and expressive states. They anticipate some aspects of Romanticism, with its emphasis on individual emotion and subjectivity. His willingness to depict himself in unconventional, even unflattering, ways was ahead of its time and speaks to a modern sensibility. He demonstrated that portraiture could be more than a mere recording of features; it could be a dynamic exploration of personality and the human condition.

His career also illustrates the adaptability required of artists during periods of profound social and political change. From the gilded halls of Versailles to the uncertainties of revolutionary Paris and exile in London, Ducreux continued to create, evolving his style and finding new patrons.

Conclusion: An Artist of Enduring Fascination

Joseph Ducreux was more than just a court painter or an eccentric dabbler in facial expressions. He was a highly skilled and versatile artist who made significant contributions to the art of portraiture. His formal portraits captured the likenesses of some of the most famous figures of his age, while his informal self-portraits stand as remarkable documents of an artist engaging with Enlightenment ideas about selfhood and emotion.

His technical proficiency in various media, his ability to navigate the treacherous political currents of his time, and, above all, the audacious originality of his expressive self-portraits ensure his place in art history. While the internet meme phenomenon has given him a quirky form of modern fame, it is his genuine artistic innovation and the captivating immediacy of his best works that continue to resonate. Joseph Ducreux remains an artist who can still surprise, amuse, and engage us, inviting us to look closer at the myriad ways the human face can reflect the inner self.