Joseph Heicke, a notable figure in 19th-century Austrian art, carved a distinct niche for himself as a painter of landscapes, genre scenes, and particularly, as a visual interpreter of the Near East. Born in Vienna on March 12, 1811, and passing away in the same city on November 6, 1861, Heicke's career unfolded during the vibrant Biedermeier period and the rising tide of Orientalism that swept across Europe. His work, though perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his contemporaries, offers valuable insights into the artistic currents, cultural exchanges, and popular tastes of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Biedermeier Vienna

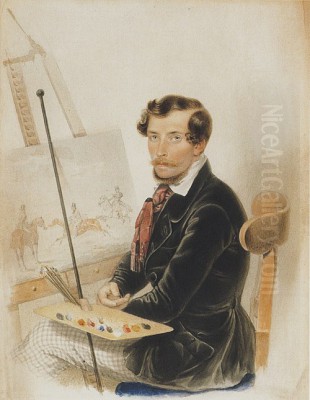

Vienna in the early to mid-19th century was a crucible of artistic activity. The Biedermeier era (roughly 1815-1848) emphasized domesticity, realism, and a certain sentimental charm in the arts. It was in this environment that Joseph Heicke likely received his initial artistic training. While specific details of his early tutelage are not extensively documented in the provided information, it is highly probable that he attended the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (Akademie der bildenden Künste Wien). This institution was a central hub for aspiring artists, fostering skills in drawing, painting, and composition.

During this period, artists like Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, known for his luminous landscapes and penetrating portraits, and Peter Fendi, celebrated for his intimate genre scenes and watercolors, were influential figures in the Viennese art world. Their emphasis on meticulous observation and capturing the nuances of everyday life would have formed part of the artistic atmosphere Heicke absorbed. The Biedermeier sensibility, with its focus on detailed representation and often anecdotal subject matter, can be discerned in aspects of Heicke's later work, even when he ventured into more exotic themes.

Heicke established himself as a professional landscape and animal painter. This dual specialization suggests a keen eye for natural detail and an ability to render both the grandeur of scenery and the vitality of living creatures. His participation in exhibitions from the mid-19th century onwards, notably at the Pesti Műegyetem (Budapest Art Association) and the Vienna Academy of Arts, indicates his active engagement with the contemporary art scene and his desire for public recognition.

The Allure of the Orient: Heicke's Journey and Artistic Response

A pivotal moment in Heicke's career, and one that would significantly shape his thematic concerns, was his journey to Egypt and the Near East in 1842. He undertook this six-month expedition as part of a group of Hungarian nobles, which notably included Count Iván Forray. This voyage was characteristic of a broader 19th-century European phenomenon: the "Grand Tour" extending beyond Italy to the lands of the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and the Holy Land. The allure of the "Orient" – a term then used to describe a vast and diverse region – captivated the European imagination, fueled by romantic literature, archaeological discoveries, and colonial expansion.

For an artist like Heicke, this journey offered a wealth of new visual stimuli: unfamiliar landscapes, vibrant marketplaces, distinct architectural styles, and diverse peoples with their unique customs and attire. He served as a professional landscape painter on this expedition, tasked with creating sketches and visual records. These on-the-spot observations would become the raw material for more finished oil paintings and, significantly, for a series of lithographs.

The collaboration with Iván Forray was particularly fruitful. Forray, an amateur artist, also documented his travels through watercolors and sketches. After their return, Forray's mother commissioned Heicke to transform her son's visual diary into a more polished and distributable form – lithographs. This project highlights Heicke's skill not just as an originator of images but also as an interpreter and refiner of another's work.

Orientalist Canvases and Prints: Crafting an Image of the East

Heicke's Orientalist works, whether his own oil paintings or the lithographs based on Forray's sketches, reflect the prevailing European fascination with the East. He often went beyond mere transcription, imbuing the scenes with a heightened sense of drama, richer colors, and more elaborate details than might have been present in the initial sketches. This approach was common among Orientalist painters, who sought to create an evocative, often idealized or romanticized, vision of the East for a Western audience.

Consider works like Café Schubra in Cairo, Café in Alexandria, and Arabs drinking coffee in front of a tent (an oil painting from 1842, also based on Forray's work). In these pieces, Heicke meticulously depicted scenes of daily life, architectural settings, and local figures. His modifications often involved enhancing the vibrancy of textiles, adding picturesque details to the background, or subtly altering compositions to improve their narrative or visual impact. For instance, he might change the color of garments or the patterns on fabrics, aiming for a more visually appealing and "exotic" representation.

This practice was not unique to Heicke. Prominent Orientalist painters such as Eugène Delacroix, whose 1832 trip to North Africa profoundly influenced his art, and Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his highly detailed and often sensual depictions of Middle Eastern life, also constructed their visions of the Orient through a combination of direct observation and artistic license. Similarly, British artists like David Roberts, famous for his lithographs of Egypt and the Holy Land, and John Frederick Lewis, who lived in Cairo for a decade, contributed to this complex visual discourse. Heicke’s work, therefore, fits into this broader European artistic engagement with the East, one that was both documentary and imaginative.

The lithograph Quarantine house, Malta provides another example of his travel-related subjects. Malta, a common stop for travelers heading to or from the Levant, had its own distinct character, and Heicke captured aspects of this Mediterranean outpost. His Orientalist output, often presented in exhibitions, catered to a public eager for glimpses into these distant and seemingly exotic lands.

Mastery in Lithography and Other Genres

Joseph Heicke's proficiency as a lithographer was a significant aspect of his artistic identity. Lithography, a relatively new printmaking technique in the 19th century, allowed for greater tonal subtlety and a more direct translation of an artist's drawing style than older methods like engraving. Heicke's skill in this medium is evident in the series he produced after Forray's watercolors. He didn't just copy; he adapted and enhanced, demonstrating an understanding of how to translate the fluidity of watercolor into the distinct language of lithography. This ability to work across media and to interpret another artist's vision speaks to his versatility.

Beyond his Orientalist themes, Heicke continued to engage with European subjects. His watercolor Planning the journey in Venice, dated 1845 and now housed in the Hungarian National Museum, captures a scene of figures in an interior, presumably discussing travel arrangements. This work, with its detailed rendering of figures and setting, aligns with the Biedermeier interest in genre scenes and narrative detail. Venice, with its unique cityscape and historical allure, was another popular destination for artists, and Heicke’s depiction adds to the rich visual tradition associated with the city, a tradition contributed to by artists like Canaletto and Francesco Guardi in the previous century, and by contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner from a more Romantic perspective.

Another notable series of works by Heicke consists of lithographs depicting Slovak peasant portraits, created around the time of the 1848 revolutions. These prints showcased Slovak individuals in their traditional occupational attire, offering a valuable ethnographic record. This interest in regional folk culture and costume was also a feature of the Romantic and Biedermeier periods, reflecting a growing awareness of national and local identities. Artists like Moritz von Schwind in Germany, though more focused on fairytale and legend, also drew from folk traditions. Heicke's Slovak series demonstrates his engagement with the diverse cultural tapestry of the Habsburg Empire.

Furthermore, Heicke produced a series of colored lithographs on the theme of Austro-Hungarian cavalry training. Military subjects, parades, and depictions of army life were popular, appealing to patriotic sentiments and an interest in the spectacle of military prowess. Artists like Albrecht Adam and his sons were renowned for their battle scenes and depictions of military life in the German states, and Heicke’s work in this area aligns with this broader European genre. His sketch Deux officiers autrichiens prenant leur petit déjeuner, vers 1860 (Two Austrian officers having breakfast, around 1860) offers a more intimate glimpse into military life, again reflecting a Biedermeier tendency towards genre.

Artistic Style, Exhibitions, and Legacy

Joseph Heicke's artistic style can be characterized by its meticulous detail, competent draftsmanship, and a sensitivity to color and atmosphere. In his Orientalist works, he balanced a degree of ethnographic observation with the romanticizing tendencies of the era. He was adept at creating compositions that were both informative and visually engaging. His ability to work effectively in oil, watercolor, and lithography underscores his technical proficiency.

His regular participation in exhibitions in Vienna and Budapest (Pest) ensured that his work was seen by a contemporary audience and contributed to his reputation. While he may not have achieved the same level of fame as some of the leading figures of Austrian Romanticism or later historical painting, his contributions are significant, particularly in the realm of Orientalist art and lithographic reproduction.

Heicke's legacy lies in his visual documentation of his travels, his skilled interpretations of Forray's work, and his broader engagement with the artistic themes of his time. His paintings and prints serve as valuable historical documents, offering insights into 19th-century European perceptions of the East, as well as depicting aspects of life within the Austrian Empire. He operated within a rich artistic milieu that included figures like Josef Danhauser, another key Biedermeier painter known for his moralizing genre scenes, and landscape painters who were pushing the boundaries of naturalism, such as Adalbert Stifter, who was also a writer.

The context of Heicke's work is also informed by the broader currents of European art. The Romantic movement, with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and the sublime beauty of nature (exemplified by artists like Caspar David Friedrich in Germany), was transitioning into the more grounded realism of the Biedermeier period and later, more objective Realism. Heicke’s landscapes, while detailed, often carried a picturesque or gently romantic quality, rather than the profound spiritual depth of a Friedrich or the dramatic intensity of a Turner.

His engagement with Orientalist themes places him in a lineage of artists fascinated by cultures beyond Europe. This fascination was complex, often intertwined with colonial ambitions and stereotypical representations, but it also produced a body of visually rich and historically significant artwork. Heicke’s approach, particularly in his lithographs after Forray, seems to have aimed at making these distant lands accessible and appealing to a European public, emphasizing the picturesque and the exotic.

Conclusion: A Viennese Artist in a Changing World

Joseph Heicke (1811-1861) was an artist whose career reflects the diverse artistic interests of mid-19th century Vienna. From the intimate genre scenes and detailed landscapes rooted in the Biedermeier tradition to his evocative depictions of the Near East, Heicke demonstrated considerable skill and adaptability. His collaboration with Iván Forray and the resulting lithographs are a particularly interesting example of artistic partnership and the dissemination of travel imagery in an era before photography became widespread.

While perhaps not a revolutionary innovator, Heicke was a competent and productive artist who contributed to the visual culture of his time. His works provide a window into the European fascination with the Orient, the ethnographic interest in regional cultures within the Habsburg Empire, and the enduring appeal of landscape and genre painting. He navigated the artistic currents of his day, leaving behind a body of work that continues to hold interest for its historical context, its aesthetic qualities, and its reflection of a world where European artists were increasingly looking beyond their own borders for inspiration. His art, viewed alongside that of contemporaries like Carl Spitzweg in Germany with his charmingly eccentric genre scenes, or the more academic history painters emerging towards the end of Heicke's life, helps to complete our understanding of the multifaceted art world of 19th-century Central Europe.