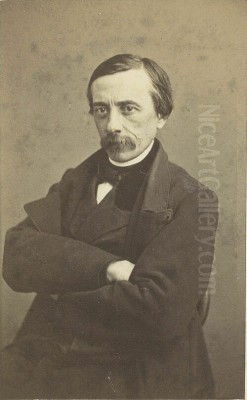

Joseph Jodocus Moerenhout, a name that resonates within the annals of 19th-century Belgian art, represents a fascinating confluence of artistic dedication and, as suggested by the provided historical accounts, a life of adventurous engagement in distant lands. Born in Ekeren, near Antwerp, in 1801 and passing away in Antwerp in 1875, Moerenhout carved a significant niche for himself primarily as a painter of horses, a subject he approached with remarkable skill and sensitivity. His oeuvre, however, extended beyond mere animal portraiture, encompassing vibrant landscapes, dynamic military engagements, and scenes of everyday life where the noble equine often played a central, if not starring, role. The narrative of his life, as pieced together from various records, also points to a remarkable chapter spent in the Pacific, specifically Tahiti, engaging in commerce and diplomacy, a period that, while seemingly distinct from his artistic pursuits in Europe, adds a layer of intrigue and complexity to his biography.

Early Artistic Development and Influences

The artistic journey of Joseph Jodocus Moerenhout began in an era where Romanticism was sweeping across Europe, influencing painting, literature, and music. While specific details of his earliest training are not always exhaustively documented, it is known that he was active in Antwerp, a city with a rich artistic heritage stretching back to masters like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck. Moerenhout, however, found his primary inspiration in a different, though equally distinguished, tradition: the Dutch Golden Age painters of the 17th century. Artists such as Paulus Potter, renowned for his intimate portrayals of cattle, Philips Wouwerman, celebrated for his lively depictions of cavalry skirmishes and hunting parties, and Aelbert Cuyp, whose luminous landscapes often featured horses and riders, undoubtedly left an indelible mark on Moerenhout’s stylistic development.

His formative years would have exposed him to the prevailing academic standards, emphasizing anatomical accuracy, skilled draughtsmanship, and balanced composition. Yet, the burgeoning Romantic spirit encouraged a more expressive and emotive approach. Moerenhout managed to synthesize these elements, creating works that were both meticulously rendered and imbued with a sense of vitality. His decision to specialize in equine subjects placed him in a lineage of artists who recognized the horse not just as an animal, but as a symbol of power, grace, and human endeavor.

The Master of Equine Art

Joseph Jodocus Moerenhout earned the laudatory, if informal, title of "the prince of horse painters." This accolade was not lightly bestowed; it reflected a genuine mastery in capturing the anatomy, movement, and spirit of horses in a multitude of settings. His canvases often teem with life, whether depicting cavalry charges, elegant hunting parties, tranquil pastoral scenes, or the bustling activity of a coaching inn. He understood the subtle nuances of equine body language, the sheen of a well-groomed coat, the strain of muscles in motion, and the intelligent gaze of the animal.

His works frequently featured landscapes, not merely as backdrops but as integral components of the narrative. These settings, whether wintry or sun-dappled, were rendered with an atmospheric quality that enhanced the overall mood of the painting. Military scenes were a common theme, allowing Moerenhout to showcase his skill in depicting dramatic action, the colorful uniforms of soldiers, and, of course, the indispensable role of horses in warfare. These were not just static portrayals but often captured a specific moment of tension, triumph, or respite. Similarly, his hunting scenes conveyed the excitement and aristocratic elegance associated with the chase.

Among his representative works, De pleisterplaats (The Resting Place), painted in 1835, exemplifies his ability to create a lively yet harmonious scene. It likely depicts travelers and their horses taking a break, a common enough subject but one that Moerenhout would have imbued with his characteristic attention to detail and atmosphere. Another notable work, Na de jacht (After the Hunt), would similarly showcase his expertise in portraying horses and riders, perhaps in a moment of relaxation and camaraderie following the exertions of the chase, with the day's quarry and the hounds adding to the narrative richness.

A later work, Plundering van Borgerhout (The Plundering of Borgerhout), dated 1866, demonstrates his capacity for tackling more complex historical or genre scenes. Such a painting would involve a multitude of figures, human and equine, within a specific historical context, demanding strong compositional skills and the ability to convey a dramatic narrative effectively. These works underscore his versatility beyond purely animal painting, integrating his equine expertise into broader historical and social tableaux.

Collaborations and Artistic Milieu

The 19th-century art world was often characterized by collaboration and shared learning. Moerenhout was no exception and is known to have engaged with several prominent contemporaries. He spent significant periods working in Amsterdam, notably between 1824 and 1831, and again in 1853. During these times, he collaborated with Andreas Schelfhout (1787-1870), a highly regarded Dutch landscape painter known for his winter scenes and panoramic views. Such collaborations often involved one artist specializing in landscapes and another adding figures or animals. Moerenhout’s skill with horses would have been a valuable asset in paintings where Schelfhout provided the scenic backdrop.

He also worked with Louis Hendrik Meijer (1809-1866), another Dutch artist, primarily known for his seascapes but also a capable painter of other subjects. Moerenhout's guidance, particularly in landscape and figure depiction, was reportedly beneficial to Meijer. These interactions highlight the collegial nature of the art scene and the cross-pollination of skills and styles.

Further evidence of his integration into the artistic community comes from his association with Charles Henri Leickert (1816-1907), a Belgian-born painter who spent much of his career in the Netherlands, also known for his atmospheric landscapes, especially winter scenes reminiscent of Schelfhout. Records indicate that Leickert traveled with Moerenhout and other artists to Brussels in 1845, suggesting a network of professional friendships and shared artistic exploration. Leickert is also noted to have worked alongside Moerenhout and Charles Rochussen (1814-1894), a Dutch painter celebrated for his historical scenes and illustrations.

Moerenhout’s contemporaries in Belgium included figures like Eugène Verboeckhoven (1798-1881), who was a preeminent animal painter, particularly of sheep and cattle, sharing Moerenhout's meticulous attention to anatomical detail. While their primary subjects differed slightly, both contributed significantly to the Belgian tradition of animal painting. Other prominent Belgian artists of the era, though perhaps in different genres, included history painters like Henri Leys (1815-1869) and Nicaise de Keyser (1813-1887), who were central figures in the Belgian Romantic movement and later historical revivals. Internationally, the Romantic fervor for dynamic and emotive subjects was championed by artists like Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) in France, whose powerful depictions of horses, such as "The Raft of the Medusa" (which prominently features human drama but his horse studies are legendary) and "Officer of the Chasseurs Commanding a Charge," set a new standard for energy and realism in animal portrayal. Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), another titan of French Romanticism, also frequently incorporated horses into his dramatic historical and orientalist scenes. In Britain, Edwin Landseer (1802-1873) was achieving immense popularity for his sentimental and majestic portrayals of animals, particularly stags and dogs. The Dutch landscape tradition continued to thrive with artists like Barend Cornelis Koekkoek (1803-1862), a contemporary of Moerenhout known for his romantic forest and river scenes.

An Unexpected Chapter: Moerenhout in Tahiti

Beyond his established career as a painter in Europe, the historical record, as presented, attributes to Joseph Jodocus Moerenhout a remarkable and extended period of activity in Tahiti, identifying him in this context also as Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout. This phase of his life, beginning around 1834, saw him engage in activities far removed from the artist’s studio, casting him in the roles of trader, diplomat, and chronicler of Polynesian culture. This Tahitian chapter, if indeed attributable to the same individual, reveals an astonishing versatility and adventurous spirit.

Upon arriving in Tahiti, Moerenhout reportedly immersed himself in commercial activities. He became a significant merchant, importing substantial quantities of goods from France and actively participating in the lucrative pearl trade. His business acumen was apparently coupled with a desire for political influence, which he sought to bolster through his commercial success. This ambition led him into the sphere of diplomacy.

He was appointed as the French Consul in Tahiti and, by 1836, had also taken on the role of United States Consul General for the Pacific Islands. These positions placed him at the heart of colonial power dynamics and local Tahitian politics. He is described as gradually infiltrating Tahiti's political structure, endeavoring to shape the island's affairs according to French and, to some extent, American interests. His diplomatic tenure was not without its complexities, including a notable conflict with the British consul and missionary George Pritchard, particularly concerning the arrival of French Catholic missionaries, whom Moerenhout permitted to land in 1836, much to Pritchard's chagrin. This incident underscored the intense Franco-British rivalry playing out in the Pacific at the time.

Chronicler of Polynesian Culture and Contentious Figure

During his time in the Pacific, Moerenhout became one of the earliest Europeans to provide a detailed account of Polynesian culture, particularly that of Tahiti. He authored a significant work titled Voyages aux îles du grand océan (Travels to the Islands of the Great Ocean). This book, while a valuable early ethnographic source, is also considered controversial, with some of its content viewed as biased or reflecting the colonial perspectives of the era. His writings offered insights into local customs, social structures, and beliefs, but his interpretations have been subject to later scholarly critique.

His relationship with the indigenous Tahitian leadership was reportedly close. He cultivated ties with local chiefs, such as Arii Taimai of Papara, which likely facilitated his commercial ventures and provided him with access to cultural information. He also interacted with Queen Pomare IV, the ruler of Tahiti, though their relationship was at times strained; she once threatened to expel him, although this was not carried out. Despite these connections, his historical accounts have been noted for occasional inaccuracies regarding names, dates, and events, making some of his narratives challenging to verify completely.

Moerenhout was not shy about expressing his opinions, often critically. He voiced disapproval of the commercial activities of British missionaries, accusing them of attempting to manipulate local legislation to protect their business interests. He also criticized the Tahitian government's administration, particularly its perceived lack of effective management concerning foreigners on the island. His own descriptions of Tahitian life could be stark, at one point characterizing it as "miserable and poor," a view that undoubtedly generated controversy and contrasted with more romanticized European notions of the Pacific islands.

His actions and pronouncements led to various legal and political disputes. For instance, he was instrumental in pushing for revisions to port regulations, which were subsequently used to prevent foreigners from landing without permission. His tenure as a US representative was also fraught, culminating in his dismissal by the American government in 1839, indicating significant disagreements or dissatisfaction with his performance in that role. Despite initial friendly relations with US Consul George Pritchard, who had assisted him with commercial and agricultural matters, their paths diverged, particularly over geopolitical and religious influences.

Later Life and Artistic Legacy

The provided information primarily details Moerenhout's artistic career in Europe and his distinct activities in Tahiti. If these two threads belong to the same individual, it implies a return to Europe or a period where his artistic pursuits continued alongside or after his Pacific ventures. Given his death in Antwerp in 1875, a significant portion of his later life would have been spent back in Europe, presumably continuing his work as a painter.

The legacy of Joseph Jodocus Moerenhout, the artist, is firmly established within the Belgian school of painting. His specialization in equine subjects, rendered with anatomical precision and romantic flair, secured him a lasting reputation. His paintings are found in museums and private collections, appreciated for their technical skill, dynamic compositions, and evocative portrayal of 19th-century life, particularly its military and pastoral aspects. His collaborations with esteemed contemporaries like Schelfhout further attest to his standing in the art world of his time.

If the Tahitian exploits are indeed part of his story, then his legacy becomes considerably more complex. As Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout, the consul and author, he would be remembered as an early European figure in Polynesian history, a contributor to ethnographic knowledge (however contested), and a participant in the colonial enterprises of the era. His book, Voyages aux îles du grand océan, despite its flaws, remains a significant document for historians studying early European contact and its impact on Tahitian society.

Conclusion: A Man of Two Worlds?

Joseph Jodocus Moerenhout, as depicted through the available information, emerges as a figure of remarkable duality. On one hand, he was a dedicated and skilled Belgian painter, a master of equine art whose canvases captured the spirit of his time with precision and romantic sensibility. His contributions to this genre are undeniable, placing him among the notable animal and landscape painters of the 19th century. His connections with artists like Andreas Schelfhout, Louis Hendrik Meijer, and Charles Henri Leickert situate him firmly within the vibrant artistic networks of Belgium and the Netherlands.

On the other hand, the narrative of his involvement in Tahiti—as a trader, diplomat for France and the United States, and author—presents a strikingly different persona, one engaged in the complex and often contentious world of colonial expansion and cultural encounter in the Pacific. This aspect of his life, filled with political maneuvering, commercial enterprise, and ethnographic documentation, adds an extraordinary dimension to the biography of an artist.

Whether these two distinct narratives represent different phases of a single, exceptionally multifaceted life, or a conflation of two similarly named individuals (a common occurrence in historical records), the story of Joseph Jodocus Moerenhout, as presented, offers a compelling glimpse into the diverse paths an individual could navigate in the 19th century. As an art historian, his paintings remain his most tangible and enduring legacy, offering a window into the artistic currents and aesthetic values of his era. The Tahitian chapter, with its own set of achievements and controversies, contributes a layer of intrigue that invites further exploration into the life and times of this notable name.