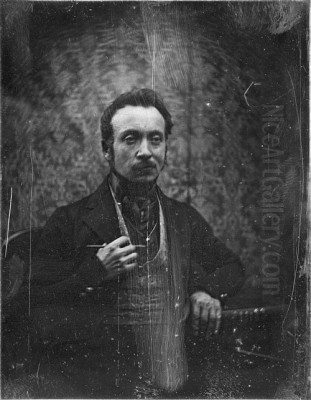

Joseph Philibert Girault de Prangey stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure in the annals of 19th-century art and science. Born into French aristocracy, he defied familial expectations to pursue a life dedicated to art, architecture, archaeology, and, most significantly, the nascent art of photography. Active during a period of immense technological and cultural change, Girault de Prangey harnessed the revolutionary daguerreotype process to embark on an ambitious project: documenting the architectural heritage of the Mediterranean basin and the Near East. His work, largely unseen during his lifetime, now provides an invaluable, and often the earliest, visual record of monuments that have since changed or vanished. He was not merely a technician but an artist with a keen eye, a scholar with deep curiosity, and an adventurer driven by a passion for the past.

Aristocratic Roots and Artistic Awakening

Joseph Philibert Girault de Prangey was born on October 21, 1804, in Langres, located in the picturesque Loire Valley region of France. His family belonged to the nobility, affording him a life of privilege and financial independence. This freedom allowed him to pursue his own interests rather than follow a predetermined career path, a choice that set the stage for his unconventional life. From an early age, he displayed a strong inclination towards the arts and a fascination with history, particularly the architecture of past civilizations.

Rejecting more conventional pursuits, Girault de Prangey dedicated himself to artistic study. He traveled to Paris to enroll at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, where he formally studied painting. This classical training honed his skills in drawing and composition, providing a foundation for his later photographic work. Even before embracing photography, he was an accomplished painter and draftsman, producing detailed studies of architectural subjects. His early works included illustrations and paintings focusing on historical sites, such as his notable studies of the Alhambra palace in Granada, created during the 1830s, showcasing his early dedication to architectural documentation.

Embracing the Daguerreotype

The year 1839 marked a pivotal moment in visual history with the public announcement of the Daguerreotype process, invented by Louis Daguerre. This groundbreaking technique, capable of capturing incredibly detailed images on silvered copper plates, spread rapidly. Girault de Prangey was among the earliest and most enthusiastic adopters. By 1841, just two years after its unveiling, he had mastered the complex and delicate process. It is believed he may have learned directly from Daguerre himself or possibly from Hippolyte Bayard, another key figure in early French photography known for his own photographic experiments and processes.

His time studying painting in Paris also brought him into contact with like-minded individuals. He met Jules Ziegler, a fellow student at the École des Beaux-Arts, who shared his fascination with the new photographic medium. Their shared interest likely spurred further exploration. Girault de Prangey also became involved with the Cercle des arts in Paris, a social and artistic group that included painters and intellectuals who were knowledgeable about, or experimenting with, the daguerreotype. This environment undoubtedly provided valuable technical exchange and encouragement for his ambitious plans.

The Grand Photographic Expedition (1842-1845)

Possessing independent means and driven by his passion for architectural history, Girault de Prangey conceived an extraordinary project: a comprehensive photographic survey of ancient monuments around the Mediterranean. Between 1842 and 1845, he embarked on an extensive tour, traveling through Italy, Greece, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, and Palestine (then part of the Ottoman Empire). This journey was remarkable not only for its geographical scope but also for its pioneering use of photography in the field under challenging conditions.

Carrying cumbersome equipment, including heavy cameras, fragile silvered plates, and volatile chemicals, he systematically documented iconic sites. His itinerary included the ruins of ancient Rome, the classical temples of Athens – notably the Parthenon and the Erechtheion on the Acropolis – the pharaonic and Islamic monuments of Cairo, the ancient city of Damascus, the Roman temples at Baalbek, and the holy sites of Jerusalem. The sheer scale of this undertaking was unprecedented. He produced over 1,000 daguerreotypes during this single expedition, creating the earliest known photographic archive of many of these locations.

His focus was primarily architectural. He sought to capture not just the general appearance of buildings and ruins but also their specific details, ornamentation, and structural forms. These images were intended as accurate records for study, reflecting his scholarly interest in architectural history and Islamic art. The journey cemented his place as one of the foremost pioneers of architectural photography and travel photography.

A Unique Photographic Vision

Girault de Prangey's daguerreotypes are more than mere historical documents; they reveal a distinct artistic sensibility and technical ingenuity. His background in painting informed his compositions, which often display a careful consideration of perspective, framing, and the interplay of light and shadow. He possessed an exceptional ability to render architectural textures and details with remarkable clarity, a quality inherent in the daguerreotype process that he exploited masterfully.

He was notably innovative in his approach. Recognizing the limitations of standard plate sizes for capturing grand structures or expansive views, he experimented with unusual formats. He frequently used oversized plates to achieve wider perspectives and employed techniques like multiple exposures to create stunning panoramic vistas, particularly effective for cityscapes like Jerusalem or architectural complexes like the Acropolis. To manage perspective distortion when photographing tall structures, he sometimes cut his daguerreotype plates into narrower vertical formats, demonstrating a practical understanding of optics and composition.

His work stands apart from many later travel photographers like Francis Frith or Maxime Du Camp, who often focused on more picturesque or romanticized views. Girault de Prangey's approach was often more analytical and systematic, driven by a desire for comprehensive documentation. Yet, his images retain a powerful aesthetic presence, capturing the silent grandeur of ancient monuments bathed in the Mediterranean sun. He also experimented with other photographic techniques, including early forms of glass plate negatives and stereoscopy, showcasing his continuous engagement with the evolving medium.

Representative Works and Publications

While Girault de Prangey did not widely exhibit his photographs during his lifetime, certain works stand out as particularly significant representations of his achievement. His extensive documentation of Islamic architecture culminated in the publication Monuments arabes d’Égypte, de Syrie et d’Asie Mineure, published between 1846 and 1851. Although produced in a small print run primarily for specialists, this volume contained lithographs based on his drawings and daguerreotypes, offering a detailed survey of mosques, madrasas, and other structures, reflecting his deep knowledge and appreciation of Islamic art and architecture.

His daguerreotypes of Jerusalem, particularly the panoramic views, are among the earliest surviving photographs of the city, offering an invaluable glimpse into its appearance in the 1840s before significant modern changes. Similarly, his images of the Acropolis in Athens, including detailed shots of the Parthenon and the Erechtheion, are considered classics of early photography. They capture the monuments with a clarity and directness that was revolutionary for the time, providing crucial data for architectural historians and archaeologists. Other notable subjects include Roman ruins in Italy and temples along the Nile in Egypt.

Beyond the Lens: Archaeology and Scholarship

Girault de Prangey's interests extended far beyond photography. He was deeply committed to archaeology and the preservation of historical heritage, particularly in his native region. He was a key figure in founding the Archaeological Society of Langres, demonstrating his dedication to local history. Perhaps even more significantly, in 1838, even before his major photographic journey, he established the Musée de Langres. This institution is recognized as one of the first municipal archaeological museums in France, showcasing his forward-thinking approach to public education and heritage preservation.

His scholarly pursuits were intertwined with his artistic practice. His travels and photographic documentation served his research into architectural history, particularly the development of Romanesque, Gothic, and Islamic styles. His publications, though limited, contributed to the academic discourse of his time. Furthermore, he continued to paint and draw throughout his life, using these skills alongside photography to record his observations. His multifaceted career exemplifies the 19th-century ideal of the gentleman scholar-artist, engaged across disciplines.

An Eccentric and Independent Spirit

Contemporaries and later historians have often described Girault de Prangey as "eccentric." His aristocratic background and independent wealth allowed him to pursue his passions without concern for commercial success or public acclaim. He seems to have been a highly individualistic and intensely private person, particularly in his later years. After his extensive travels, he retreated to his estate near Langres, where he designed and cultivated an elaborate oriental-inspired garden, complete with exotic plants and architectural follies, reflecting his enduring fascination with the East.

His apparent lack of interest in promoting his photographic work is striking. Unlike contemporaries such as Gustave Le Gray or Charles Nègre, who actively sought commissions, exhibited their work, and engaged with the burgeoning photographic market, Girault de Prangey kept his vast collection of daguerreotypes largely to himself. They were meticulously cataloged and stored in custom-made wooden boxes on his estate, remaining hidden from public view for decades after his death. This reclusiveness contributed to his relative obscurity during the later 19th and much of the 20th century.

Connections and Context: The Wider Artistic World

While Girault de Prangey operated with considerable independence, he was not entirely isolated from the artistic and intellectual currents of his time. His education placed him in Paris during a vibrant period. His association with Jules Ziegler and the Cercle des arts connected him with other artists exploring photography. His work also resonates with the broader 19th-century European fascination with the "Orient," a theme explored by prominent painters like Eugène Delacroix and Jean-Léon Gérôme. While direct interaction with these famous Orientalist painters is not documented, Girault de Prangey's detailed, objective documentation offers a different, perhaps more ethnographic, perspective compared to their often romanticized or dramatic canvases. Even the Neoclassicism of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, with its meticulous detail, finds a distant echo in Girault de Prangey's precise renderings.

His focus on architectural documentation aligns him with other architect-scholars and illustrators of the era, such as Pascal Coste, who also traveled and documented Middle Eastern architecture, or even Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, whose passion for historical accuracy, albeit focused on French Gothic, mirrors Girault de Prangey's dedication to recording the past. His pioneering photographic work predates or runs parallel to other early photographers documenting distant lands, setting a high standard for those who followed.

Belated Recognition and Enduring Legacy

Joseph Philibert Girault de Prangey died on December 7, 1892, at his estate. For decades after his death, his groundbreaking photographic work remained largely unknown, stored away and forgotten. It was not until the late 20th century that his vast archive of daguerreotypes, drawings, and notes began to surface, initially discovered on his estate. This rediscovery sparked immense interest among photographic historians, curators, and collectors.

The true value and importance of his contribution became dramatically apparent in 2003 when a selection of his daguerreotypes appeared at auction. One image, depicting Temple 112 in Athens (Temple of Olympian Zeus), fetched a staggering $922,488 (purchased by Sheikh Saud Al-Thani of Qatar), setting a world record price for a daguerreotype at the time. This event catapulted Girault de Prangey into the spotlight, cementing his status as a major figure in photographic history.

His legacy rests on several pillars: he was one of the earliest and most prolific daguerreotypists; he undertook the first known systematic photographic survey of Mediterranean and Near Eastern monuments; his technical innovations expanded the possibilities of the medium; and his work provides an unparalleled historical record of world heritage sites. His images bridge the gap between scientific documentation and artistic expression, capturing the essence of architectural forms with both precision and aesthetic grace.

Major Collections: Preserving the Archive

Today, the works of Joseph Philibert Girault de Prangey are held in several prestigious institutions, ensuring their preservation and accessibility for study and appreciation. The most significant repository is the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF) in Paris, which holds a vast collection of his daguerreotypes, along with related drawings, prints, and manuscripts. This collection forms the core resource for understanding the breadth and depth of his work.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (Met) in New York also possesses a substantial collection of his daguerreotypes, particularly from his travels in Italy, Greece, and Egypt. These have been featured in major exhibitions dedicated to his work and early photography. The Musée d'Orsay in Paris, renowned for its 19th-century art collection, also holds examples of his photographs, paintings, and drawings. Additionally, institutions like the Musée Gréuiller in Bulle, Switzerland, have exhibited his work, reflecting growing international recognition. Beyond public institutions, a number of his daguerreotypes reside in important private collections around the world.

Conclusion: A Singular Visionary

Joseph Philibert Girault de Prangey emerges from the shadows of history as a singular visionary. Combining the resources of his aristocratic background with an insatiable curiosity and a mastery of multiple disciplines – painting, architecture, archaeology, and photography – he created a body of work that remains astonishing in its scope, quality, and foresight. As one of the very first photographers to systematically document architectural heritage on such a grand scale, he not only preserved invaluable visual records of the past but also demonstrated the profound potential of the photographic medium just years after its invention. His technical ingenuity, his scholarly rigor, and his unique artistic eye secure his place as a pivotal, if long-overlooked, pioneer whose contributions continue to enrich our understanding of both world history and the history of photography itself.