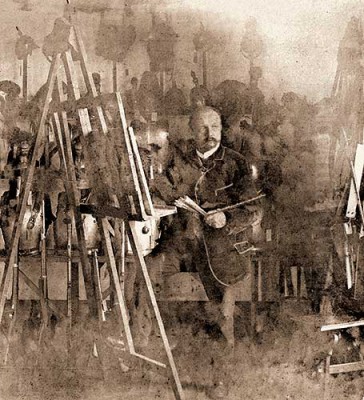

Louis Braun, a prominent German artist of the 19th and early 20th centuries, carved a significant niche for himself as a history painter, particularly renowned for his immense and immersive panorama paintings depicting war scenes. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, a strong sense of naturalism, and dramatic compositions, offered audiences of his time a unique and compelling window into the tumult and grandeur of historical and contemporary conflicts. While the panorama as an art form eventually waned in popularity, Braun's contributions remain a testament to a specific era of visual storytelling and historical representation.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born Ludwig Braun on September 23, 1836, in Schwäbisch Hall, in the Kingdom of Württemberg, his artistic inclinations were nurtured from a young age. His initial formal training took place in Stuttgart, a significant cultural center, where he studied under the tutelage of Bernhard von Neher (often cited as Bernhard von Neuhoeft in some records) and Heinrich Rustige. Both were respected figures in the German academic tradition, and their guidance would have instilled in Braun a strong foundation in drawing, composition, and the prevailing aesthetics of historical painting, which emphasized accuracy and narrative clarity.

The pivotal moment in Braun's artistic development came in 1859 when he journeyed to Paris. The French capital was then the undisputed epicenter of the art world, and Braun sought to learn from one of its most celebrated masters of military and historical painting, Horace Vernet. Vernet, known for his vast canvases depicting Napoleonic battles and scenes from the French conquest of Algeria, was a master of capturing the dynamism and sprawling scale of warfare. Studying under Vernet profoundly influenced Braun's approach, particularly in handling complex group scenes, equine anatomy, and the dramatic rendering of battle. This Parisian sojourn exposed him to a more vibrant and perhaps less rigidly academic style than he might have encountered solely in Germany, and it undoubtedly shaped his ambition to tackle large-scale historical subjects.

The Panorama Phenomenon and Braun's Specialization

The 19th century witnessed the rise and immense popularity of the panorama, a unique form of public entertainment and artistic expression. These were massive, 360-degree paintings housed in specially constructed circular buildings, designed to create an illusion of reality, transporting the viewer directly into the depicted scene. Panoramas often showcased famous battles, distant cities, or significant historical events, offering an immersive experience akin to modern virtual reality or epic cinema. Louis Braun emerged as one of the foremost practitioners of this demanding art form, particularly in the realm of military subjects.

His style was marked by a commitment to naturalism and an almost photographic attention to detail, especially concerning uniforms, weaponry, and the topography of battlefields. This dedication to accuracy was often fueled by firsthand experience; Braun was known to accompany armies during campaigns, such as the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), sketching and gathering material that would later inform his monumental works. This direct observation lent an air of authenticity and immediacy to his paintings, which resonated strongly with contemporary audiences eager for vivid depictions of national triumphs and historical turning points. His ability to manage the vast scale of panorama canvases while maintaining compositional coherence and dramatic impact was a hallmark of his skill.

Masterpieces of Conflict: Key Works by Louis Braun

Louis Braun's reputation rests heavily on several key panoramic works that captivated audiences and solidified his status as a leading battle painter. Among these, the "Battle of Sedan" stands out as one of his most famous and successful creations. Depicting a decisive moment in the Franco-Prussian War, this panorama, completed around 1880, was celebrated for its dramatic intensity and detailed portrayal of the Prussian victory. Such works served not only as artistic achievements but also as powerful expressions of national pride and historical narrative, particularly in the newly unified German Empire.

Another significant work is the "Panorama of the Battle of Murten," completed in 1893. This piece is particularly noteworthy as it depicted a much earlier conflict, the 1476 battle where the Swiss Confederacy decisively defeated Charles the Bold of Burgundy. The choice of a medieval subject, rather than a contemporary one, allowed Braun to explore different historical aesthetics and narratives. The "Battle of Murten" panorama is of exceptional importance as it is one of the few surviving examples of this art form and is considered a Swiss national treasure, meticulously preserved and still capable of conveying the artist's original vision.

Other panoramas, such as the "Battle of Lützen," "Battle of Mars-la-Tour," and "The Entry of King Ludwig II of Bavaria into Innsbruck," further demonstrated his versatility in depicting various historical periods and types of ceremonial or conflict scenes. These works were often exhibited in major cities like Munich, Berlin, Frankfurt, and Dresden, attracting large crowds and contributing to the popular understanding and memory of these events.

Artistic Style: Detail, Drama, and Naturalism

Louis Braun's artistic style was deeply rooted in the academic traditions of 19th-century history painting, yet it was also infused with a dynamic naturalism that made his war scenes particularly compelling. He possessed a remarkable skill for rendering intricate details – the glint of light on a sabre, the texture of a uniform, the strain on a horse's muscle. This meticulousness did not, however, result in static or lifeless compositions. Instead, Braun masterfully orchestrated vast numbers of figures, horses, and landscape elements into cohesive and dramatic narratives.

His compositions often employed sweeping perspectives to convey the scale of battle, drawing the viewer's eye across the canvas to various focal points of action. The use of light and shadow was crucial in creating atmosphere and highlighting key moments within the chaotic swirl of combat. While his work served to glorify military endeavors, particularly those involving German forces, there was also an undeniable element of realism in his depiction of the effort and human drama inherent in warfare. His figures, though often heroic, were rendered with an anatomical accuracy and a sense of movement that brought them to life. This blend of academic precision, naturalistic observation, and dramatic storytelling defined his unique contribution to the genre of battle painting.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Louis Braun operated within a vibrant and competitive European art scene, particularly rich in history and battle painters. His teacher, Horace Vernet (1789-1863), was a towering figure whose influence extended to many artists specializing in military themes. In France, Braun's contemporaries included masters of the genre like Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891), renowned for his incredibly detailed and smaller-scale depictions of Napoleonic battles, and the duo of Alphonse de Neuville (1835-1885) and Édouard Detaille (1848-1912), who became famous for their vivid and often patriotic portrayals of the Franco-Prussian War from a French perspective. Their work, like Braun's, fed a public appetite for images of heroism and national conflict.

In Germany, Braun was part of a generation of artists who documented and celebrated the rise of the German Empire. Adolph Menzel (1815-1905), though broader in his subject matter, produced significant historical paintings, including scenes from the life of Frederick the Great, with a characteristic realism and psychological depth. Anton von Werner (1843-1915) became almost the official painter of Prussian glory, his works often depicting key political and military events, such as the proclamation of the German Empire at Versailles. While Braun specialized in the immersive panorama, these artists worked in more traditional formats, yet all contributed to the visual culture of historical and national identity.

The field of panorama painting itself had other notable practitioners. For instance, the French painters Paul Philippoteaux (1846-1923) and his father Félix Philippoteaux were famous for their "Cyclorama of Gettysburg." In the Netherlands, Hendrik Willem Mesdag (1831-1915) created the "Panorama Mesdag," depicting the seascape of Scheveningen, which still exists and is a prime example of a non-military panorama. Russian art also saw powerful battle painters like Vasily Vereshchagin (1842-1904), whose works often carried a strong anti-war message, contrasting with the more celebratory tone of some Western European battle paintings.

Earlier 19th-century figures like Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) with "The Raft of the Medusa" and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863) with "Liberty Leading the People" had already pushed the boundaries of historical and contemporary event painting, infusing it with Romantic dynamism and emotional intensity, setting a precedent for large-scale, impactful works. Even the Neoclassical grandeur of Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), with his depictions of Napoleonic heroism, laid some groundwork for the celebration of national leaders and military prowess in art. Braun's work, therefore, can be seen as part of a long and evolving tradition of history painting, adapted to the unique medium of the panorama. His later career also saw him take on a teaching role, becoming a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, where figures like Wilhelm von Kaulbach (1805-1874) had earlier held significant influence, further embedding Braun within the academic art establishment of his time.

The Technical Demands of Panorama Painting

Creating a panorama was a colossal undertaking, demanding not only artistic skill but also considerable logistical and technical expertise. Louis Braun, like other panorama specialists, would have first created numerous studies and a smaller-scale model, or maquette, of the final painting. This allowed him to work out the complex composition, perspective, and lighting before embarking on the full-size canvas, which could be hundreds of feet long and dozens of feet high.

The canvas itself was typically painted in sections by a team of assistants under the master's direct supervision, though Braun was known for his hands-on approach. The challenge lay in seamlessly blending these sections and maintaining a consistent perspective that would create a convincing illusion when viewed from the central platform of the rotunda. Special attention had to be paid to the lighting of the panorama, often achieved through a combination of natural light from a skylight and carefully concealed artificial lights, designed to enhance the realism of the scene. Furthermore, a "faux terrain" – a three-dimensional foreground with real or replica objects like cannons, rocks, and foliage – was often placed between the viewing platform and the painting, blurring the line between the painted image and the viewer's space, thereby heightening the immersive effect. Braun's success in this medium speaks to his mastery over these multifaceted challenges.

War, Art, and National Identity

Louis Braun's career coincided with a period of intense nationalism and frequent military conflicts in Europe. His panoramas, particularly those depicting German victories, played a role in shaping public perception and collective memory. These were not merely artistic spectacles; they were powerful tools for fostering national pride, commemorating sacrifices, and reinforcing particular historical narratives. The Franco-Prussian War, for example, was a pivotal event in German unification, and Braun's depictions of its battles contributed to the heroic mythology surrounding this conflict.

The immersive nature of the panorama made these historical lessons particularly potent. Viewers were not passive observers but were made to feel as if they were participants in or direct witnesses to the events unfolding around them. This emotional engagement helped to solidify the messages embedded in the artwork. While today we might view such works with a more critical eye regarding their propagandistic elements, in their time, they were a significant part of the cultural landscape, reflecting and shaping the zeitgeist of an era defined by burgeoning empires and the glorification of military strength. Braun's participation in military campaigns, gathering sketches and firsthand impressions, added a layer of perceived authenticity that was highly valued by his audience.

Later Career and the Decline of the Panorama

Louis Braun continued to be a prolific artist throughout his career, adapting his skills to various commissions. He produced not only panoramas but also smaller easel paintings, illustrations, and designs for decorative projects. His reputation as a specialist in military and equestrian subjects ensured a steady stream of work. He also held a professorship at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, passing on his knowledge to a new generation of artists.

However, the late 19th and early 20th centuries brought about significant changes in both art and popular entertainment. The advent of photography had already begun to challenge painting's role as the primary medium for documentary representation. More significantly for the panorama, the rise of cinema offered a new, dynamic, and even more immersive form of visual storytelling. Moving pictures quickly captured the public's imagination, and the grand, static panoramas began to seem old-fashioned. The specialized buildings required to house them were expensive to maintain, and many were eventually repurposed or demolished.

As a result, the panorama as an art form experienced a steep decline in popularity. Many of Louis Braun's monumental works, being site-specific, were lost when their rotundas were dismantled. This is a common fate for panoramas, and it contributes to why artists like Braun, who were hugely famous in their day, are less widely known now than painters who worked in more portable and collectible formats.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Louis Braun passed away in Munich on March 18, 1916, during the midst of the First World War, a conflict that would dramatically reshape Europe and attitudes towards warfare. By the time of his death, the art world had also undergone radical transformations, with modern art movements like Cubism and Expressionism challenging the very foundations of academic and naturalistic art that Braun represented.

Despite the decline of the panorama and the shifting tides of artistic taste, Louis Braun's legacy endures, particularly within the specialized field of military and panorama painting. His surviving works, most notably the "Battle of Murten" panorama, stand as important historical documents and impressive artistic achievements. They offer invaluable insights into 19th-century visual culture, the public's fascination with immersive experiences, and the ways in which art was used to construct and disseminate historical narratives and national identities.

Art historians and researchers studying 19th-century popular culture, military history, and the evolution of visual media recognize Braun's significant contribution. His dedication to detail, his ability to manage vast and complex compositions, and his role in bringing history to life for a mass audience secure his place as a master of his chosen genre. While perhaps not as universally recognized today as some of his contemporaries who worked in other formats, Louis Braun remains a key figure for understanding the unique artistic phenomenon of the panorama and its powerful hold on the 19th-century imagination. His paintings are a vivid reminder of a time when painted canvases could offer the most spectacular and immersive visual experiences available.