The annals of art history are replete with figures whose contributions, while significant, sometimes become obscured by the passage of time or, more perplexingly, by confusion with other artists sharing similar names. Louis Chalon, a French artist active in the first half of the 18th century, with documented birth and death years of 1687 and 1741 respectively, presents such a case. His work, primarily focused on landscape painting and, to some extent, mythological and allegorical themes, places him within a vibrant period of French art, yet details about his life and a comprehensive catalogue of his oeuvre remain subjects for deeper scholarly investigation. This exploration seeks to illuminate the known aspects of Louis Chalon (1687-1741), distinguishing him from other artists of the same name, particularly a later Art Nouveau artist, and situating him within the artistic currents of his time.

Distinguishing Between Artists: A Necessary Clarification

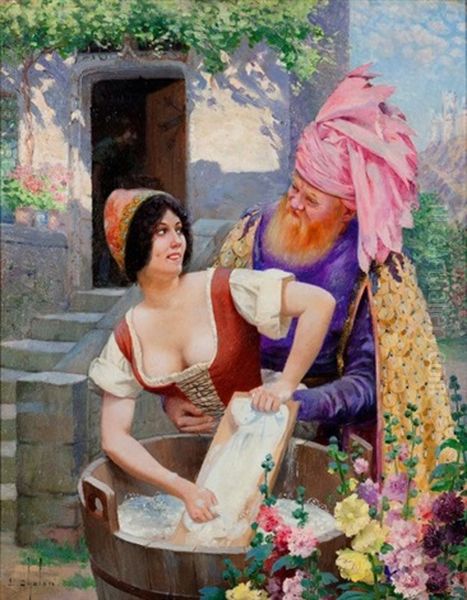

Before delving into the specifics of Louis Chalon (1687-1741), it is crucial to address a common point of confusion. Art historical records also feature another notable Louis Chalon (1862-1915), a prominent figure in the Art Nouveau movement, celebrated for his sculptures, illustrations, and decorative arts. Works such as "La Fée" (The Fairy), "La Lavandière" (Laundress), and illustrations for Boccaccio's "Decameron" are firmly attributed to this later artist. Furthermore, any discussions linking a Louis Chalon to the artistic development of John William Waterhouse (1849-1917) would pertain to this 19th/20th-century figure. The present discussion, however, is exclusively focused on the earlier Louis Chalon, whose artistic career unfolded in the late Baroque and emerging Rococo periods of France. Similarly, references to historical figures like Louis II de Chalon-Arlay, Prince of Orange, involved in medieval territorial disputes, are entirely separate and bear no relation to the artist in question.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in a Changing France

Louis Chalon was born in 1687, a time when France, under the long reign of King Louis XIV, was the undisputed cultural powerhouse of Europe. The artistic landscape was dominated by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, founded in 1648, which upheld a strict hierarchy of genres, with history painting (including mythological and religious subjects) at its apex, followed by portraiture, genre scenes, landscape, and still life. Charles Le Brun (1619-1690), who had been the dominant force in French art for decades as First Painter to the King and director of the Gobelins Manufactory, passed away when Chalon was a mere child. However, Le Brun's influence on the Academy's teachings and the classical, grandiose style he championed, often referred to as French Classicism or the Louis XIV style, would have still permeated the artistic education available in Paris during Chalon's formative years.

While specific details of Chalon's early training are not extensively documented in the provided information, it is highly probable that he received instruction within the academic system or was apprenticed to an established master. The provided text suggests he may have studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and was potentially taught by Charles Le Brun. Given Le Brun's death in 1690, direct tutelage for an extended period would be impossible. However, Chalon could have been exposed to Le Brun's pedagogical methods through his successors or studied his works and theoretical writings, which remained influential. Artists like Antoine Coypel (1661-1722) or Charles de La Fosse (1636-1716), who were prominent figures at the Academy in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, represented a transition, incorporating richer color and a somewhat softer line, influenced by Venetian and Flemish art, particularly the works of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640). This evolving classicism, sometimes termed "Rubenism," offered a counterpoint to the more austere "Poussinism" that Le Brun had initially favored, derived from the work of Nicolas Poussin (1594-1665).

Chalon's active period as an artist is noted between 1715 and 1734. This timeframe coincides with the Régence period (1715-1723), following the death of Louis XIV, and the early reign of Louis XV. This era witnessed a shift in artistic taste away from the formal grandeur of Versailles towards more intimate, lighthearted, and decorative styles, which would culminate in the Rococo movement. Artists like Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721), a near contemporary of Chalon, pioneered the "fête galante" genre, capturing idyllic scenes of aristocratic leisure with a delicate touch and subtle emotional depth.

Specialization in Rhine Landscapes

A significant aspect of Louis Chalon's artistic output was his dedication to landscape painting, particularly views of the Rhine River, referred to as "Rijngezichten." This specialization suggests an interest in capturing the specific topography and atmosphere of this important European waterway. The Rhine, with its dramatic castles, picturesque towns, and varied scenery, had long been a subject for artists, particularly Dutch and Flemish painters of the 17th century. Masters such as Jan van Goyen (1596-1656) and Salomon van Ruysdael (c. 1602-1670) had established a strong tradition of river landscape painting in the Netherlands.

Chalon's focus on Rhine landscapes between 1715 and 1734 indicates a market for such views, though the provided information notes that the remuneration for these works might have been relatively low, potentially limiting the scope or ambition of these particular creations. Despite this, the choice of subject is noteworthy. French landscape painting in the early 18th century was evolving. While the idealized, classical landscapes of Poussin and Claude Lorrain (1600-1682) remained highly esteemed and influential, there was also a growing appreciation for more naturalistic and topographically specific views. Artists like Jean-Baptiste Oudry (1686-1755), another contemporary, though more famous for his animal paintings and still lifes, also produced landscapes. Later in the century, Claude Joseph Vernet (1714-1789) would gain immense fame for his series of French seaports and dramatic landscapes.

Chalon's Rhine views would have likely combined elements of observed reality with picturesque conventions. The tradition of Dutch Italianate painters like Jan Both (c. 1610/18-1652) or Nicolaes Berchem (1620-1683), who depicted idealized sunny landscapes, might also have played a role, as their works were widely collected and admired across Europe. Without specific examples of Chalon's "Rijngezichten" readily available for analysis, one can only speculate on their stylistic characteristics, but they would have likely reflected the prevailing tastes for landscapes that were both recognizable and aesthetically pleasing.

Mythological and Allegorical Compositions

Beyond his landscape work, Louis Chalon (1687-1741) is also credited with creating paintings on mythological and allegorical themes. This aligns perfectly with the expectations for an academically trained artist of his era, as history painting, which encompassed these subjects, was considered the most prestigious genre. Such works allowed artists to demonstrate their erudition, skill in depicting the human figure, and ability to convey complex narratives and ideas.

One specific mythological work mentioned in connection with this Louis Chalon is a painting titled "Circe." The enchantress Circe, from Homer's "Odyssey," was a popular subject in art, offering opportunities to depict a powerful female figure, exotic settings, and dramatic narrative moments. The description provided suggests that Chalon's "Circe" aimed to capture the character's allure and divine heritage, possibly emphasizing her connection to the sun god Helios, her father. The portrayal of such a subject would require a strong command of anatomy, composition, and the visual language of classical mythology. Artists like Sebastiano Ricci (1659-1734) in Italy, or French painters like François Lemoyne (1688-1737), a direct contemporary of Chalon who achieved great success with large-scale mythological decorations (such as the ceiling of the Salon d'Hercule at Versailles), were also actively engaged with such themes. Lemoyne, in particular, represented the vibrant, light-filled evolution of the grand style that would influence the Rococo.

The creation of mythological and allegorical works often involved a deep understanding of classical texts and iconographical traditions. Artists would consult emblem books and mythological handbooks to ensure the accuracy and appropriateness of their depictions. The challenge lay in reinterpreting these ancient stories in a way that was fresh and engaging for an 18th-century audience. The style for such paintings in Chalon's time could range from the more robust, dynamic late Baroque to the lighter, more graceful emerging Rococo, often characterized by luminous colors, sensuous figures, and elegant compositions. François Boucher (1703-1770), though slightly younger than Chalon, would become the quintessential master of Rococo mythological painting, infusing his subjects with charm and playful eroticism.

Artistic Style and Influences in Context

Defining the precise artistic style of Louis Chalon (1687-1741) is challenging without a broad corpus of securely attributed and accessible works. However, based on his period of activity and his engagement with both landscape and mythology, we can infer certain characteristics. His work would have been rooted in the French classical tradition, emphasizing clarity, order, and a degree of idealization, especially in his mythological pieces. The influence of the Academy, with its focus on drawing (disegno) and the study of classical antiquity and Renaissance masters like Raphael (1483-1520), would have been foundational.

However, the early 18th century was also a period of stylistic transition. The grandeur of the Louis XIV era was giving way to a preference for more approachable and decorative art. The "querelle des anciens et des modernes" (quarrel of the ancients and moderns) in literature had its parallels in art with the debate between the "Poussinistes" (who prioritized line and drawing) and the "Rubenistes" (who championed color and a more painterly approach). By Chalon's time, the Rubenistes had largely gained ascendancy, leading to a richer palette and more dynamic compositions in French painting.

It is plausible that Chalon's landscapes, particularly his Rhine views, might have shown an influence from 17th-century Dutch landscape painting, known for its naturalism and sensitivity to light and atmosphere. Artists like Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1628-1682) or Meindert Hobbema (1638-1709) had set a high standard for realistic and evocative landscape depiction. If Chalon traveled to the Rhine region, he would have had direct exposure to its scenery and perhaps to local artistic traditions.

In his mythological works, Chalon would have been working within a long tradition, but also responding to contemporary tastes. The elegance and grace that characterized the emerging Rococo style, seen in the works of Watteau or Lemoyne, might have found its way into his interpretations of classical myths. The emphasis would likely have been on narrative clarity, pleasing compositions, and skillful rendering of the human form. The works of Italian Baroque artists, widely known through prints and collected works, such as those by Annibale Carracci (1560-1609) or Guido Reni (1575-1642), also continued to be important models for mythological painting.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu of Early 18th-Century Paris

Louis Chalon operated within a bustling Parisian art world. His contemporaries included a diverse range of talents. Jean-Antoine Watteau, as mentioned, was revolutionizing genre painting. In the realm of portraiture, Hyacinthe Rigaud (1659-1743) and Nicolas de Largillière (1656-1746) were the dominant figures, creating grand and insightful likenesses of the aristocracy and bourgeoisie. Rigaud, in particular, was known for his majestic state portraits, such as his iconic depiction of Louis XIV.

For mythological and historical painting, alongside François Lemoyne, artists like Jean-François de Troy (1679-1752) and Jean Restout II (1692-1768) were prominent. De Troy was known for his elegant "tableaux de mode" as well as his historical and mythological scenes, often imbued with a Rococo sensibility. Restout, from a family of artists, maintained a more sober, classical approach, often working on large-scale religious commissions.

In landscape, while Chalon focused on Rhine views, other artists were exploring different facets of the genre. Jean-Baptiste Oudry, known for his hunting scenes and animal paintings, also created powerful landscapes and was influential as the director of the Beauvais and later the Gobelins tapestry manufactories. The tradition of decorative landscape painting, often integrated into interior design schemes, was also thriving.

The print market was crucial during this period, disseminating images of famous artworks and allowing artists to reach a wider audience. Engravers like Bernard Picart (1673-1733), who was also a painter and book illustrator, played a vital role in this visual culture. It is possible that Chalon's works, particularly if they achieved some popularity, might have been reproduced as prints, although specific evidence for this is lacking in the provided summary.

The social life of artists often revolved around the Academy, private salons, and studios. Patronage came from the Crown, the Church, the aristocracy, and increasingly, from wealthy financiers and merchants. The taste of these patrons significantly shaped artistic production. The shift towards smaller, more intimate paintings suitable for Parisian townhouses (hôtels particuliers) rather than grand royal palaces influenced the scale and subject matter of much art produced during the Régence and the early reign of Louis XV.

The Question of Legacy and Artistic Lineage

The provided information mentions that Louis Chalon's daughter, Christina Chalon (1748-1808), was also an artist. However, the dates for Christina Chalon place her birth seven years after the death of Louis Chalon (1687-1741). This discrepancy suggests that Christina Chalon was likely the daughter of a different Chalon, perhaps from the Dutch branch of artists with that surname, or that the attribution of Christina as the daughter of this specific Louis Chalon is an error. The Dutch artist Christina Chalon is indeed a recognized figure, known for her drawings and etchings in the style of Adriaen van Ostade. If this connection is inaccurate for the French Louis Chalon (1687-1741), it removes a potential avenue for tracing direct artistic lineage.

The influence of an artist can also be seen in the work of pupils or followers. While the provided text suggests Louis Chalon (1687-1741) may have been a student of Charles Le Brun (or at least within his academic sphere of influence), there is no specific mention of students he himself might have taught. His legacy, therefore, would primarily reside in his surviving works and their impact, however subtle, on the broader artistic trends of his time.

The confusion with the later Louis Chalon (1862-1915) unfortunately complicates the assessment of the 18th-century artist's legacy. When works or influences are misattributed, it becomes difficult to form a clear picture of each individual's distinct contribution. For Louis Chalon (1687-1741), his specialization in Rhine landscapes and his engagement with mythological themes mark him as an artist working within established, yet evolving, genres of his era. His paintings would have contributed to the visual culture of early 18th-century France, reflecting contemporary tastes and artistic practices.

Exhibitions and Documentary Evidence

Information regarding specific exhibitions featuring the works of Louis Chalon (1687-1741) during his lifetime or posthumously is not detailed in the provided summary. The Paris Salon, the official exhibition of the Académie Royale, became a regular, public event from 1737 onwards. If Chalon was active until 1741 and was a member of the Academy or an approved artist, he might have exhibited there in its early years. However, his main documented active period is cited as 1715-1734. Earlier, less regular Salons did occur, and artists also found venues in private collections and through dealer networks.

Documentary evidence, such as mentions in contemporary inventories, sale catalogues, or art criticism, would be crucial for reconstructing a more complete picture of Chalon's career and reputation. The very existence of his name in art historical records, along with his birth and death dates and specialization, indicates that such documentation exists, even if it is not widely synthesized or easily accessible. The reference to his Rhine landscapes ("Rijngezichten") being known, albeit perhaps not highly paid, suggests a degree of recognition for this part of his oeuvre.

The painting "Circe," attributed to him, serves as a tantalizing glimpse into his mythological work. Further research into museum collections, archives, and scholarly articles on 18th-century French painting might uncover more securely attributed works or provide more context for his career. The challenge often lies in sifting through records where names may be common or inconsistently recorded.

Conclusion: An Artist Meriting Further Study

Louis Chalon (1687-1741) emerges as a figure representative of the artistic currents of early 18th-century France. Active during a period of significant stylistic and social change, he navigated the demands of the art market by specializing in landscapes, particularly views of the Rhine, and by producing works in the more prestigious genre of mythological painting. His artistic formation would have been shaped by the legacy of French Classicism as established by figures like Charles Le Brun and Nicolas Poussin, but also by the burgeoning taste for more colorful, dynamic, and graceful art that characterized the transition from the late Baroque to the Rococo.

His contemporaries included some of the most celebrated names in French art, such as Watteau, Lemoyne, Oudry, Rigaud, and Largillière. While Chalon may not have achieved the same level of fame as these luminaries, his work contributed to the rich tapestry of artistic production in his era. The primary challenge in fully appreciating his contribution lies in the scarcity of readily available, comprehensively documented information specifically pertaining to him, and the potential for confusion with other artists of the same name, most notably the later Art Nouveau artist.

Further scholarly research dedicated to meticulously tracing his oeuvre, identifying his patrons, and contextualizing his work more precisely within the Parisian art scene of the 1710s, 1720s, and 1730s would undoubtedly enrich our understanding of this artist. For now, Louis Chalon (1687-1741) remains a somewhat enigmatic painter, a testament to the many talented individuals who contributed to the vibrant artistic landscape of 18th-century Europe, whose stories still await fuller telling. His known focus on Rhine landscapes and mythological subjects like "Circe" provides a foundation upon which a more complete portrait of his artistic identity might one day be constructed, allowing him to take his rightful, clearly defined place in the history of French art.