Luigi Ademollo (1764–1849) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of Italian Neoclassicism. A painter, draughtsman, and etcher of considerable talent and prodigious output, Ademollo's career spanned a transformative period in European art, witnessing the zenith of Neoclassicism and the burgeoning stirrings of Romanticism. Born in Milan and ultimately passing away in Florence, he was quintessentially Italian, his artistic journey taking him through the major artistic centers of the peninsula and leaving an indelible mark, particularly through his extensive fresco cycles. His active period, primarily from the late 18th century through the first half of the 19th century, saw him engage with historical, biblical, and mythological themes, executed with a characteristic theatricality and a keen eye for narrative detail.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Milan

Luigi Ademollo was born in Milan in 1764, a city with a rich artistic heritage, then under Austrian Habsburg rule. This environment, while perhaps not as central to the nascent Neoclassical movement as Rome, still possessed institutions and artistic currents that would shape the young Ademollo. His formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Brera Academy (Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera) in Milan. Founded officially in 1776 by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, the Brera was rapidly becoming a vital center for artistic education in Lombardy, promoting Enlightenment ideals and a return to classical principles.

At the Brera, Ademollo had the opportunity to study under several distinguished Milanese artists who were instrumental in shaping his early artistic sensibilities. Among his masters were Giulio Traballesi (1727–1812), a painter and etcher known for his religious and historical subjects, who would have instilled in Ademollo a solid grounding in academic drawing and composition. Another influential teacher was Pietro Martire Armani, whose guidance would have further refined Ademollo's technical skills.

He also learned from Giocondo Albertolli (1742–1839), a Swiss-born architect and ornamental designer who became a professor of ornament at the Brera. Albertolli's emphasis on classical decorative motifs and architectural precision likely influenced Ademollo's later work in large-scale fresco decoration, where the integration of figures with architectural settings was paramount. Furthermore, Domenico Aspari (1746–1831), a painter and engraver known for his vedute (cityscape views) and architectural perspectives, would have contributed to Ademollo's understanding of spatial representation and perspective, crucial for a painter aspiring to monumental works. The Milanese artistic milieu, with figures like Andrea Appiani (1754-1817) also rising to prominence as a leading Neoclassical painter, provided a stimulating backdrop for Ademollo's formative years.

Theatrical Beginnings and the Roman Sojourn

Before establishing himself primarily as a painter of frescoes and easel works, Luigi Ademollo's early career involved work in stage design. This experience in the theatre was not uncommon for artists of the period and proved to be profoundly influential on his later artistic style. The demands of scenography – creating dramatic effects, managing complex figural arrangements within a defined space, and conveying narrative quickly and effectively – honed his compositional skills and instilled in him a penchant for theatricality that would become a hallmark of his paintings. He traveled to various Italian cities, engaging in this line of work, which provided practical experience in large-scale design and rapid execution.

In 1785, Ademollo made a pivotal move to Rome. At this time, Rome was the undisputed epicenter of the Neoclassical movement, attracting artists from all over Europe. It was a city electric with artistic debate and discovery, fueled by the archaeological unearthing of Pompeii and Herculaneum, and the influential writings of scholars like Johann Joachim Winckelmann, who championed the "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" of classical art. Here, Ademollo would have been exposed to the works of leading Neoclassicists such as Anton Raphael Mengs (though Mengs had died in 1779, his influence was pervasive) and Pompeo Batoni (1708-1787), whose grand portraits and history paintings set a high standard.

The artistic environment in Rome was also shaped by figures like the great etcher Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720-1778), whose dramatic views of Roman antiquities had captivated Europe, and the sculptor Antonio Canova (1757-1822), who was then establishing his international reputation as the foremost Neoclassical sculptor. Ademollo's arrival in Rome placed him at the heart of this artistic ferment, allowing him to absorb firsthand the principles of Neoclassicism, study ancient Roman art, and interact with a vibrant community of international artists. This Roman period was crucial for solidifying his artistic direction and ambitions. It is also noted that he collaborated with the Swiss landscape painter Abraham-Louis-Rodolphe Ducros (1748-1810) on decorations for the Capitoline Palace in Rome, an experience that would have further broadened his artistic horizons.

Florence: A Canvas for Monumental Ambition

While Rome provided intellectual and artistic stimulation, it was in Florence that Luigi Ademollo found the most significant patronage and the grandest canvases for his talents, particularly in the realm of fresco painting. He settled in Florence, which, under the Habsburg-Lorraine Grand Dukes, was also a significant cultural center. His skills as a decorator of large spaces were highly sought after, and he embarked on numerous commissions that would secure his reputation.

The most prestigious of these were his extensive works for the Palazzo Pitti, the grand ducal palace in Florence. Beginning in the late 18th century and continuing into the early 19th, Ademollo was entrusted with decorating several important rooms and chapels within this vast complex. His work in the Palatine Chapel (Cappella Palatina) is particularly noteworthy. Here, he executed a series of frescoes depicting scenes from the Old Testament, demonstrating his mastery of complex multi-figure compositions and his ability to convey dramatic biblical narratives.

Among the key frescoes in the Palatine Chapel are the Transportation of the Ark of the Covenant and David and Goliath. These works showcase Ademollo's Neoclassical training in their clarity of form and balanced compositions, yet they also possess a dynamic energy and emotional intensity that hint at the emerging Romantic sensibilities. The figures are often muscular and heroic, rendered with anatomical precision, and arranged in dynamic, almost stage-like, groupings that underscore the drama of the depicted events. His use of color, while often adhering to a Neoclassical palette, could also be rich and vibrant, enhancing the visual impact of his scenes.

Beyond the Palatine Chapel, Ademollo also contributed to the decoration of other spaces within the Palazzo Pitti. He painted the View of the Room of the Ark (also known as the Sala dell'Arca or Room of the Niches), showcasing his ability to integrate painted scenes with existing architectural frameworks. He was also responsible for frescoes in the Corridor of Noah's Ark (Corridoio dell'Arca di Noè), further demonstrating his proficiency in depicting complex biblical narratives across expansive wall surfaces. These commissions at the Pitti Palace solidified his status as one of the leading monumental painters in Tuscany. Other notable Florentine Neoclassical painters active during parts of this period included Pietro Benvenuti (1769-1844), who also undertook major commissions in the city.

Signature Works and Thematic Concerns

Beyond his extensive fresco cycles, Luigi Ademollo produced a significant body of easel paintings, drawings, and prints that further illuminate his artistic concerns and stylistic range. One of his most recognized easel paintings is The Death of Germanicus, created around 1800. This subject, popular among Neoclassical artists (Nicolas Poussin had famously depicted it earlier), allowed for the exploration of themes of virtue, stoicism, and tragic heroism. Ademollo’s rendition is characterized by its dramatic composition, with the dying Roman general surrounded by grieving soldiers and family, their expressive gestures and postures conveying the solemnity and emotional weight of the moment. The painting exhibits a careful attention to historical detail in costume and setting, typical of the Neoclassical desire for archaeological accuracy, combined with a theatrical staging that draws the viewer into the scene.

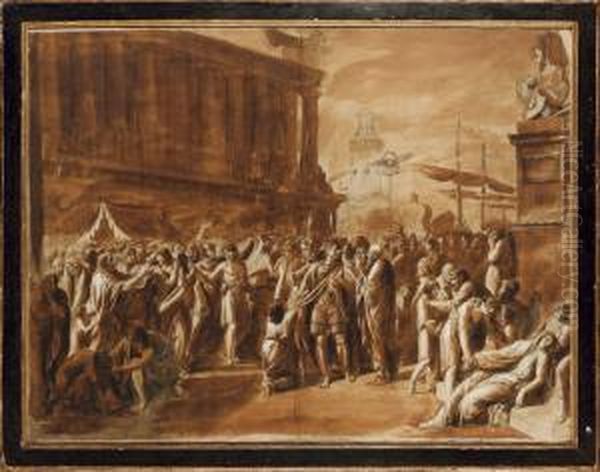

Another important early work is Gli ostaggi cartaginesi (The Carthaginian Hostages), painted around 1790. This drawing, depicting the Roman consul Marcus Atilius Regulus being taken as a hostage by the Carthaginians, is imbued with a palpable sense of drama and revolutionary spirit, reflecting the turbulent political climate of the era. The composition is bold, with strong contrasts of light and shadow, and the figures convey a powerful sense of resolve and sacrifice. Such historical subjects, often drawn from Roman history, provided Neoclassical artists like Ademollo with opportunities to explore moral and civic virtues.

His religious works were also numerous. The fresco Entry of Christ into Jerusalem, on which he reportedly collaborated with Abraham-Louis-Rodolphe Ducros, is noted for its vibrant colors and exotic depiction of the landscape, including palm trees, showcasing an interest in orientalizing details that sometimes appeared in Neoclassical art. Ademollo's ability to handle large-scale narrative, whether biblical or historical, was a consistent strength. He also produced etchings, such as The Victory of Religion and Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter, demonstrating his versatility across different media. His illustrations for editions of classical texts, like Virgil's Aeneid, further underscore his engagement with the classical world.

Artistic Style: Neoclassicism with a Theatrical Flair

Luigi Ademollo's artistic style is firmly rooted in Neoclassicism, yet it is not a rigid or purely academic interpretation of the movement. He embraced the core tenets of Neoclassicism: clarity of line, balanced composition, an emphasis on drawing (disegno), and the choice of noble and edifying subjects drawn from classical antiquity, the Bible, or history. His figures often possess a sculptural quality, reflecting the Neoclassical admiration for ancient Greek and Roman sculpture. The influence of masters like Raphael and the Carracci, revered by Neoclassical theorists, can also be discerned in his work.

However, Ademollo's style is distinguished by a pronounced theatricality and a dynamic energy that sometimes pushes beyond the "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" advocated by Winckelmann. His experience in stage design clearly informed his approach to composition, leading to dramatic groupings of figures, expressive gestures, and a sense of movement that enlivens his narratives. This theatrical quality, while effective in conveying emotion and engaging the viewer, sometimes led to criticisms from purists who favored a more restrained and idealized form of Neoclassicism, such as that practiced by the French master Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), whose influence was immense across Europe.

There are also discernible elements that connect Ademollo to earlier traditions and foreshadow Romanticism. Some scholars note a lingering Rococo sensibility in the elegance and decorative qualities of certain passages, particularly in his ornamental work. More significantly, the emotional intensity, the interest in dramatic historical events, and the occasional "wildness" or "eclecticism" noted by some critics, align with the burgeoning Romantic spirit that was beginning to challenge Neoclassical dominance in the early 19th century. Artists like Felice Giani (1758-1823), another prolific Italian decorator, also displayed a more dynamic and less rigidly classical style. Ademollo's work thus occupies an interesting position, embodying mainstream Neoclassicism while also displaying individualistic tendencies that reflect the complex artistic currents of his time. His contemporary, Vincenzo Camuccini (1771-1844), was perhaps the leading Neoclassical painter in Rome, known for his large historical canvases, offering a point of comparison for Ademollo's own ambitions in grand-scale painting.

Drawings, Prints, and Versatility

Luigi Ademollo's artistic output was not confined to monumental frescoes and easel paintings. He was also a prolific and accomplished draughtsman and printmaker, activities that complemented his work in other media and provided different avenues for his artistic expression. His drawings, often preparatory studies for larger compositions or finished works in their own right, reveal his skill in capturing form, movement, and expression with fluency and precision. These works on paper, ranging from quick sketches to highly finished presentation drawings, offer insights into his creative process and his mastery of academic figure drawing.

Subjects for his drawings mirrored those of his paintings, encompassing biblical scenes, episodes from classical history and mythology, and allegorical figures. Works like The Carthaginian Hostages demonstrate his ability to create powerful and dramatic compositions even on a smaller scale, using pen and ink with wash to achieve strong chiaroscuro effects. These drawings were not merely technical exercises; they were imbued with the same narrative energy and theatricality that characterized his paintings.

Ademollo also engaged in printmaking, primarily etching. This medium allowed for the wider dissemination of his compositions and ideas. His etchings often reproduced his own painted designs or explored similar themes. For instance, his illustrations for an edition of Virgil's Aeneid would have been executed as prints, allowing him to reach a broader audience and contribute to the Neoclassical revival of interest in classical literature. Printmaking also offered a different set of technical challenges and expressive possibilities, and Ademollo's activity in this field underscores his versatility as an artist. Other Italian artists of the period, such as Giuseppe Cades (1750-1799), an early proponent of Neoclassicism in Rome, also worked extensively as draughtsmen, highlighting the importance of drawing in the Neoclassical tradition. The Bolognese artist Pelagio Palagi (1775-1860), a contemporary who worked across painting, sculpture, and decorative arts, similarly demonstrated a wide-ranging talent.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Artistic Milieu

Luigi Ademollo operated within a vibrant and competitive artistic world, interacting with numerous contemporaries and, on occasion, collaborating on projects. His collaboration with the Swiss landscape specialist Abraham-Louis-Rodolphe Ducros on the Entry of Christ into Jerusalem for the Capitoline Palace in Rome is a documented instance of such teamwork. Ducros, known for his picturesque watercolors and gouaches of Roman landscapes and ruins, would have brought a different sensibility to the project, potentially influencing the landscape elements of the fresco. Such collaborations, while not always extensively documented, were not uncommon, especially for large decorative schemes.

Ademollo was also acquainted with other leading figures in the Italian art scene. While specific details of his interactions with Giuseppe Bezzuoli (1784-1855), a prominent Florentine painter who leaned more towards Romanticism in his later career, are not extensively recorded, they would have certainly been aware of each other's work in Florence. Bezzuoli, like Ademollo, undertook significant commissions in the Palazzo Pitti. The artistic circles in cities like Rome and Florence were relatively tight-knit, and artists often competed for the same patrons and commissions, while also influencing and learning from one another.

Ademollo's name is often mentioned in art historical accounts alongside other key Italian Neoclassical painters like Vincenzo Camuccini, Felice Giani, and Giuseppe Cades, indicating his recognized status within that movement. Camuccini, based in Rome, was a dominant figure, celebrated for his large-scale historical and religious paintings executed in a grand, academic Neoclassical style. Giani, on the other hand, represented a more exuberant and less orthodox strand of Neoclassicism, known for his dynamic and rapidly executed frescoes. Cades was an important early figure in the Roman Neoclassical scene. The artistic production of Gaspare Landi (1756-1830), another significant Neoclassical painter active in Rome and Piacenza, also provides context for Ademollo's career. The transition towards Romanticism can be seen in the work of artists like Francesco Hayez (1791-1882), who began his career in a Neoclassical vein but became the leading figure of Italian Romantic painting.

Later Life, Family, and Critical Reception

Luigi Ademollo continued to be active as an artist into the 19th century, though detailed information about his later years is somewhat scarcer. He passed away in Florence in 1849, having lived through a period of profound political and cultural change in Italy and Europe. His artistic legacy was continued, in a sense, by his nephew, Carlo Ademollo (1824–1911). Carlo became a notable painter in his own right, specializing in historical subjects and battle scenes, particularly those related to the Italian Risorgimento, thus reflecting the shift in artistic themes towards nationalistic and contemporary historical events in the later 19th century.

Regarding Ademollo's personal circumstances, there are some indications that, despite his numerous commissions, he may have faced financial difficulties at certain points in his career. For instance, it's mentioned that he undertook theatre decoration work in Milan that remained unfinished due to funding issues. Such challenges were not uncommon for artists, even those with established reputations, as patronage could be inconsistent and large projects often involved complex financial arrangements.

The critical reception of Luigi Ademollo's work has evolved over time. During his lifetime and in the period immediately following, he was generally well-regarded as a skilled and prolific decorator, a master of the Neoclassical style who could execute large-scale commissions with competence and dramatic flair. His frescoes in the Palazzo Pitti were, and remain, significant examples of early 19th-century monumental decoration in Florence.

However, as artistic tastes shifted away from Neoclassicism towards Romanticism and later movements, his reputation, like that of many Neoclassical artists, may have experienced a period of relative neglect. Some later critics pointed to perceived weaknesses in his work, such as a lack of profound depth in the rendering of nudes or drapery, or a tendency towards a "wild" or "eclectic" style that prioritized narrative effect over formal rigor. His theatricality, once a strength, could also be seen as overly dramatic or artificial by later sensibilities. Nevertheless, modern art historical scholarship has increasingly recognized his importance as a key figure in Italian Neoclassicism, particularly in Tuscany, and has undertaken a more nuanced assessment of his contributions, acknowledging both his adherence to Neoclassical principles and his individual stylistic traits.

Enduring Legacy

Luigi Ademollo's legacy primarily resides in his extensive fresco cycles, particularly those in Florence, which stand as testaments to his skill, industry, and ambition. His ability to manage vast wall surfaces and populate them with dynamic, narrative compositions was remarkable. Works like those in the Palatine Chapel of the Palazzo Pitti remain important documents of the artistic tastes and religious patronage of the period. They offer a window into how biblical and historical narratives were visualized and interpreted within a Neoclassical framework, infused with Ademollo's characteristic dramatic sensibility.

While perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his contemporaries like Canova or David, Ademollo played a crucial role in the dissemination and adaptation of Neoclassical principles in Italy. He was a versatile artist, proficient in fresco, easel painting, drawing, and printmaking, and his prolific output contributed significantly to the visual culture of his time. His work demonstrates the vitality of the Neoclassical movement in Italy and its capacity for regional variation and individual expression.

Academic research continues to shed light on his career, his specific commissions, and his place within the broader context of late 18th and early 19th-century European art. His paintings and drawings are held in various museums and private collections, allowing for ongoing study and appreciation. Luigi Ademollo remains a significant figure for understanding the complexities of Italian Neoclassicism, an artist who successfully navigated the demands of large-scale public decoration while developing a distinctive, if sometimes debated, personal style. His contribution to the artistic heritage of Florence, in particular, is undeniable and continues to be valued.