Marie-Victor-Émile Isenbart stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art. Born in an era of profound artistic transformation, Isenbart carved a niche for himself as a dedicated painter of the French rural landscape, particularly the idyllic and evocative scenery of his native Franche-Comté region. His work, while rooted in the observational traditions that preceded Impressionism, also embraced the burgeoning movement's sensitivity to light and atmosphere, making him a fascinating bridge between established Salon practices and the avant-garde.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Besançon

Marie-Victor-Émile Isenbart was born on March 3, 1846, in Besançon, the historic capital of the Franche-Comté region in eastern France. This area, known for its rolling hills, dense forests, and the winding Doubs River, would become the enduring muse for much of his artistic output. Growing up surrounded by such natural beauty undoubtedly instilled in him a deep appreciation for the landscape, a sentiment that would later translate into canvases imbued with a quiet, pastoral charm.

Details regarding Isenbart's early artistic training are not extensively documented, but it is known that he was a student of Antonin Fanart. Like many aspiring artists of his time, he would have likely followed a traditional academic path, honing his skills in drawing and composition. The artistic environment of Besançon, while not as bustling as Paris, had its own rich heritage, notably being the birthplace of the great Realist painter Gustave Courbet, whose influence would resonate throughout the region and beyond. Isenbart's development occurred during a period when Courbet's revolutionary approach to art, emphasizing the depiction of ordinary life and unidealized nature, was challenging the established norms of the French Academy.

Debut at the Paris Salon and Emerging Style

Isenbart made his debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1872. The Salon was the official, state-sponsored art exhibition in France and, for most of the 19th century, the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers. To be accepted into the Salon was a significant achievement, indicating a certain level of technical proficiency and adherence to, or at least a palatable negotiation with, prevailing artistic tastes.

His early works exhibited at the Salon began to showcase his predilection for landscape painting. He focused on capturing the specific character of the French countryside, often returning to the familiar vistas of Franche-Comté. His style during this period, while demonstrating academic skill, also started to reveal an interest in the more nuanced and atmospheric qualities of nature, a departure from the highly finished and often idealized landscapes favored by stricter academicians. He was less concerned with grand historical or mythological narratives set in nature, and more with the intrinsic beauty of the land itself.

The Allure of Franche-Comté: Isenbart's Enduring Muse

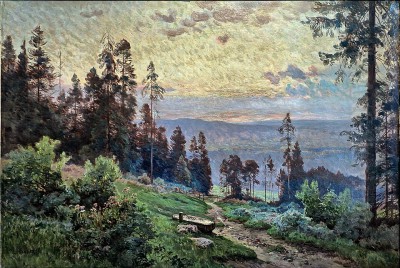

The Franche-Comté region, with its diverse topography ranging from the plains of the Saône valley to the Jura Mountains, provided Isenbart with an inexhaustible source of inspiration. He was particularly drawn to the subtle interplay of light and shadow across the fields, the misty mornings that softened the contours of the land, and the tranquil scenes of rural life. His paintings often depict winding rivers, quiet ponds, dense undergrowth, and pastoral scenes with grazing cattle or solitary figures, all rendered with a sensitivity that speaks of a deep connection to his subject matter.

Unlike some of his contemporaries who sought out dramatic or exotic locales, Isenbart found profound beauty in the familiar. His commitment to his native region aligns him with a tradition of French landscape painters who celebrated the specific character of their local environments, artists such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, who famously painted the Forest of Fontainebleau, or Charles-François Daubigny, known for his depictions of the Oise River. Isenbart’s work contributes to this rich legacy, offering a specific vision of Franche-Comté’s unique charm.

Artistic Style: Realism, Barbizon, and Impressionistic Sensibilities

Isenbart's artistic style is often characterized as being influenced by the Realist movement, particularly by Gustave Courbet, who was also from Franche-Comté (Ornans). Courbet’s revolutionary insistence on painting what he could see, without idealization, had a profound impact on the art world. Isenbart, while perhaps not as radical in his social or artistic stance, shared Courbet’s commitment to depicting the tangible reality of the landscape. He was considered by some to be a "follower" of Courbet, absorbing the master's dedication to truth in representation.

His work also shows affinities with the Barbizon School, a group of painters active from the 1830s to the 1870s who gathered in the village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau. Artists like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña championed direct observation of nature and often painted en plein air (outdoors) to capture the immediate effects of light and atmosphere. Isenbart’s focus on rural scenery, his nuanced rendering of natural light, and his often muted, earthy palette echo the concerns of the Barbizon painters.

While Isenbart consistently exhibited at the official Salon and became a member of the Salon des Artistes Français in 1888, his work increasingly incorporated elements associated with Impressionism. This is particularly evident in his treatment of light and atmosphere. He excelled at capturing the ephemeral qualities of mist, the soft glow of dawn or dusk, and the dappled sunlight filtering through leaves. Though he may not have adopted the broken brushwork or the vibrant, unmixed colors of core Impressionists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, or Alfred Sisley, his sensitivity to the fleeting moments of nature and his desire to convey an immediate sensory experience align him with the broader Impressionistic ethos.

Key Themes and Representative Works

Isenbart's oeuvre is dominated by landscapes that evoke a sense of peace and timelessness. He was a master of depicting the subtle transitions of seasons and times of day. His paintings often feature water – rivers, ponds, and watering holes – reflecting the sky and adding a luminous quality to his compositions.

Among his representative works, several stand out for their characteristic charm and technical skill:

_Chasseur dans un sous-bois du Jura_ (Hunter in a Jura Undergrowth): This title, more accurately translated than some initial interpretations, suggests a scene typical of the Jura region, known for its forests and hunting traditions. Such a work would likely showcase Isenbart's ability to render the dense foliage and filtered light of a woodland interior, a challenging subject that many landscape painters, from Jacob van Ruisdael to Théodore Rousseau, tackled.

_Mist in the Morning at Belieu_ (_Brouillard du matin à Belieu_): This painting exemplifies Isenbart's skill in capturing atmospheric effects. Belieu, a village in Franche-Comté, likely provided him with numerous opportunities to observe and paint the morning mists that often settle in the valleys. The depiction of mist requires a subtle handling of tone and color to convey a sense of depth and ethereal beauty, a hallmark of Isenbart's mature style. Such atmospheric concerns were central to Impressionists like Monet in his Impression, soleil levant or Sisley in his depictions of floods and snow.

_Vaches à l'abreuvoir, crépuscule_ (Cows at the Watering Place, Twilight): This work combines Isenbart's interest in pastoral scenes with his sensitivity to the specific light of twilight. The inclusion of cattle, a common motif in the work of Barbizon painters like Constant Troyon and Rosa Bonheur, grounds the scene in the realities of rural life. The crepuscular light would allow for a play of soft shadows and warm, fading colors, creating a tranquil and slightly melancholic mood.

Other works by Isenbart, often titled simply with the location or a descriptive phrase like "River Landscape" or "Edge of the Forest," consistently demonstrate his dedication to capturing the essence of the French countryside. He often painted scenes around Noël-Cerneux, another locality in Franche-Comté, further emphasizing his deep regional focus.

Recognition and Career Milestones

Isenbart's dedication and talent did not go unrecognized during his lifetime. His regular participation in the Paris Salon from 1872 onwards established his reputation. In 1888, he became a member of the Société des Artistes Français, the organization that took over the running of the annual Salon after the French government relinquished control. This membership signified his acceptance within the mainstream art establishment.

Further accolades followed. He received honorable mentions and medals at various Salons and exhibitions. Notably, he was awarded a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1889, a prestigious international event that showcased achievements in art, science, and industry. He received another bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1900, also held in Paris. These awards underscore the esteem in which his work was held.

A significant honor was bestowed upon him in 1897 when he was made a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honour (Légion d'honneur). This is France's highest order of merit, both military and civil, and its conferral upon an artist signifies substantial recognition of their contribution to French culture. This award placed him in the company of many other distinguished artists of his era, including academic painters like William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Léon Gérôme, as well as more progressive figures.

Isenbart in the Context of His Contemporaries

To fully appreciate Isenbart's position, it's helpful to consider the broader artistic landscape of his time. The late 19th century was a period of dynamic change and diverse artistic currents. The academic tradition, upheld by figures like Alexandre Cabanel and Ernest Meissonier, still held considerable sway, particularly within the Salon. However, Realism, championed by Courbet and Jean-François Millet, had already challenged its dominance by focusing on contemporary life and ordinary people.

The Barbizon School, with artists like Corot, Daubigny, and Rousseau, had paved the way for a more direct and personal approach to landscape painting, emphasizing plein air work and a faithful rendering of natural effects. Isenbart clearly absorbed lessons from these predecessors.

Then came Impressionism, which officially burst onto the scene with its first independent exhibition in 1874, just two years after Isenbart's Salon debut. Figures like Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, Degas, Sisley, and Berthe Morisot revolutionized painting with their emphasis on capturing fleeting visual impressions, their use of bright, often unmixed colors, and their distinctive broken brushwork. While Isenbart did not fully adopt the radical techniques of the core Impressionists, his heightened sensitivity to light and atmosphere shows a clear engagement with their concerns. He can be seen as an artist who successfully navigated a path that incorporated modern sensibilities while still finding acceptance within the established Salon system, much like Édouard Manet in his later career, or even landscape painters like Henri Harpignies who maintained a more traditional structure but with a fresh observation of nature.

Other contemporaries who explored landscape with varying approaches include Paul Cézanne, who would push towards Post-Impressionism with his structured compositions, and Georges Seurat, who developed Pointillism. While Isenbart's path was distinct from these more avant-garde figures, his work represents an important and popular vein of landscape painting that appealed to a broad audience. His contemporaries also included successful Salon landscape painters like Léon Germain Pelouse or Jules Breton, who often incorporated figures into his rural scenes.

There is no specific record of direct collaborations or intense rivalries between Isenbart and these specific figures in the provided information, but artists of the period were certainly aware of each other's work through exhibitions, art journals, and shared artistic circles in Paris. Isenbart's consistent Salon presence and his focus on the Franche-Comté landscape would have made his work familiar to many.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Marie-Victor-Émile Isenbart passed away in 1921. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its sincerity, technical skill, and evocative portrayal of the French countryside. While he may not have achieved the revolutionary status of some of his contemporaries, his contribution to French landscape painting is undeniable.

His works are held in the collections of several French museums, including those in Besançon, Brest, Le Mans, and Rouen. This institutional recognition affirms his place in the narrative of French art. In recent years, his paintings have also performed well at auctions, indicating a sustained interest among collectors who appreciate his gentle, atmospheric landscapes.

Isenbart's legacy lies in his ability to capture the poetic essence of a specific region, Franche-Comté, and to do so with a style that gracefully blended traditional observational skills with a modern sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He represents a type of artist crucial to the art ecosystem: one who, while not necessarily at the cutting edge of the avant-garde, produced consistently high-quality work that resonated with the public and contributed to the rich visual culture of his time. His paintings offer a window into a quieter, more pastoral France, rendered with affection and a keen eye for the subtle beauties of the natural world. He remains an important representative of French landscape painting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a testament to the enduring appeal of nature depicted with skill and heart.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Rural France

Marie-Victor-Émile Isenbart's career spanned a period of immense artistic innovation and societal change. He navigated this era by remaining true to his vision of painting the landscapes he knew and loved. His depictions of Franche-Comté are more than mere topographical records; they are imbued with a lyrical quality, a deep understanding of the nuances of light and atmosphere, and a quiet reverence for the rural way of life.

As an artist who successfully exhibited at the Salon, received national honors, and whose work continues to be valued, Isenbart holds a respectable place in the annals of French art. He may be seen as a bridge figure, whose art acknowledged the solid foundations of Realism and the Barbizon School while embracing the atmospheric concerns that were central to Impressionism. His paintings serve as a lasting tribute to the beauty of the French countryside and as a reminder of the diverse talents that enriched the art world of his time. For those who appreciate landscape painting that combines faithful observation with poetic sensibility, the works of Marie-Victor-Émile Isenbart offer a rewarding and enduring pleasure.