Melchior Fritsch, an Austrian painter active during the 19th century, holds a specific, if somewhat understated, place in the annals of art history. While not as globally renowned as some of his contemporaries, his contributions as both an artist and an educator, particularly in shaping the careers of other notable painters, mark him as a figure of interest. Born in 1826 and passing away in 1889, Fritsch's life and career unfolded during a period of significant artistic transformation in Austria and across Europe, witnessing the transition from late Biedermeier sensibilities through Historicism and Realism towards the nascent stirrings of Impressionism and its regional variations.

The Artistic Landscape of 19th-Century Austria

To understand Melchior Fritsch's context, it's essential to consider the vibrant and evolving artistic environment of 19th-century Austria, particularly Vienna. The early part of the century was dominated by the Biedermeier style, characterized by its detailed realism, focus on domesticity, portraiture, and local landscapes, exemplified by artists like Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller. As the century progressed, the grand style of Historicism, heavily promoted by the establishment and the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts, took center stage, with monumental paintings depicting historical, mythological, or allegorical scenes. Hans Makart became the towering figure of this era, his opulent style defining much of Viennese official art.

However, alongside these dominant trends, a quieter but persistent engagement with landscape painting continued. Artists sought to capture the beauty of the Austrian Alps and the countryside, initially in a romanticized or highly detailed manner. Towards the latter half of the century, influenced by international movements like the Barbizon School in France and a growing desire for more direct, unembellished representation, Austrian artists began to explore more naturalistic and atmospheric approaches to landscape. This set the stage for the development of "Stimmungsimpressionismus," or Austrian Mood Impressionism, a distinct regional variant of Impressionism that emphasized capturing the mood and atmosphere of a scene through light and color, often with a lyrical or melancholic undertone.

Fritsch's Role as an Educator

Melchior Fritsch's most documented impact lies in his role as a painting instructor. In the 19th century, private tutelage was a common and crucial path for aspiring artists, especially for women, who often faced more restricted access to formal academic training. Fritsch is noted for having taught several students, the most prominent among them being Olga Wisinger-Florian (1844-1926).

Wisinger-Florian, initially a concert pianist, turned to painting in the 1870s due to a hand injury. She sought instruction from various artists, including Melchior Fritsch. Her other teachers included August Schaeffer von Wienwald and, significantly, Emil Jakob Schindler (1842-1892). Schindler was a leading figure in Austrian Mood Impressionism, and his influence, along with that of his circle (which included artists like Carl Moll, Tina Blau, and Marie Egner), was profound on Wisinger-Florian's development.

While the specifics of Fritsch's pedagogical methods are not extensively detailed in readily available sources, his tutelage of Wisinger-Florian in the 1870s places him within the crucial developmental period of her artistic journey. It is plausible that Fritsch provided her with foundational skills in drawing, composition, and oil painting techniques, which she then further developed under Schindler's more avant-garde influence. The fact that Wisinger-Florian went on to become a significant representative of Austrian Mood Impressionism suggests that her early teachers, including Fritsch, played a part in nurturing her talent.

Melchior Fritsch's Artistic Oeuvre

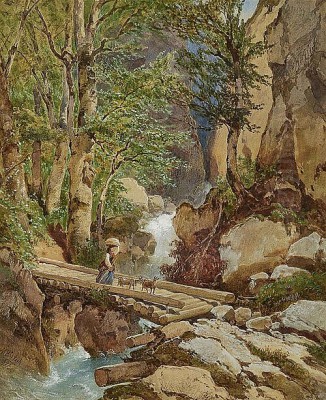

Information regarding Melchior Fritsch's own body of work is somewhat limited compared to his more famous students or contemporaries. However, known titles provide insight into his artistic preoccupations, which appear to align with the landscape traditions of his time.

His painting 《Alpensee》 (Alpine Lake), dated 1872, clearly indicates a focus on the majestic Alpine scenery that captivated so many Austrian artists. Such works typically aimed to convey the grandeur of nature, the play of light on water and mountains, and the specific atmospheric conditions of high-altitude environments. The date 1872 places this work in a period when naturalism was gaining traction, suggesting a move away from purely romanticized depictions towards a more direct observation of nature.

Another work, 《Bauernhof (in den Alpen)》 (Farmstead in the Alps), dated circa 1870, further underscores his interest in rural and Alpine themes. Farmsteads were common subjects, allowing artists to explore not only the landscape but also elements of vernacular architecture and the human presence within nature. These subjects resonated with a sense of national identity and a romantic appreciation for pastoral life, even as industrialization was beginning to transform society.

A third title mentioned, 《Gmander-See》, likely refers to the Gmundner See (Lake Gmunden) in the Salzkammergut region, a popular area for landscape painters due to its picturesque beauty. This further solidifies Fritsch's engagement with characteristic Austrian landscapes.

Given these titles and the period in which he worked, it is reasonable to assume Fritsch's style was rooted in 19th-century landscape realism, possibly with an emerging sensitivity to atmospheric effects that would later characterize Mood Impressionism. His work likely emphasized careful observation, competent draftsmanship, and a traditional approach to composition and color, providing a solid foundation for his students.

The Context of Austrian Mood Impressionism

Although it's not definitively stated that Fritsch himself was a Mood Impressionist, his connection to Olga Wisinger-Florian and his activity during the period of its emergence make it relevant to discuss this movement. Austrian Mood Impressionism, or Stimmungsimpressionismus, was less about the analytical deconstruction of light and color seen in French Impressionism (think Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro) and more focused on conveying the subjective emotional response to a landscape – its "Stimmung" or mood.

Artists like Emil Jakob Schindler, Tina Blau, Marie Egner, Olga Wisinger-Florian, Theodor von Hörmann, and later Carl Moll, often worked en plein air, at least in their studies, to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Their subjects frequently included forests, riverbanks, gardens, and rural scenes, often imbued with a sense of tranquility, melancholy, or intimacy. Color palettes could be vibrant but were often subtly modulated to evoke specific times of day or emotional states.

Fritsch's teaching in the 1870s coincided with the formative years of this movement. While Schindler is often seen as its central figure, the broader artistic environment, including teachers like Fritsch who provided foundational training, contributed to the ecosystem in which Mood Impressionism could flourish.

Contemporaries and the Broader Artistic Milieu

Melchior Fritsch worked during a dynamic period in European art. Beyond the Austrian sphere, landscape painting was undergoing significant evolution. The French Barbizon School, with artists like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Jean-François Millet, had already championed a more naturalistic and direct approach to landscape in the mid-century, influencing artists across Europe.

In Germany, artists like Adolph Menzel were pushing the boundaries of realism, while the Düsseldorf school of painting had a strong tradition of landscape. Later in the century, German Impressionism would emerge with figures such as Max Liebermann, Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt.

Within Austria itself, besides the Mood Impressionists, other artistic currents were present. The aforementioned Hans Makart represented the peak of academic Historicism. Anton Romako, a highly individualistic painter, created works that defied easy categorization, often with psychological intensity. The Vienna Secession, which would radically transform Austrian art, was still a few years in the future at the time of Fritsch's death in 1889, but the seeds of modernism were being sown. Artists like Gustav Klimt, who would become a leader of the Secession, were beginning their careers within the established academic system before breaking away.

Fritsch's career, therefore, spanned a bridge between more traditional 19th-century approaches and the newer currents that would lead to modern art. His focus on landscape and his role as an educator placed him within a vital, if not always headline-grabbing, segment of the art world.

Challenges in Reconstructing Fritsch's Full Profile

One of the challenges for art historians when studying figures like Melchior Fritsch is the relative scarcity of comprehensive documentation compared to artists who achieved greater fame or were more closely associated with revolutionary movements. His primary recognition seems to stem from his connection to Olga Wisinger-Florian. This is not uncommon; many competent and influential teachers are primarily remembered through the achievements of their students.

The precise nature of his artistic philosophy, the full extent of his oeuvre, and details of his personal life and exhibition history are not as readily accessible as those for, say, Emil Jakob Schindler or Hans Makart. This means that our understanding of Fritsch is often pieced together from mentions in the biographies of others and from the few works that are documented.

It is important to note a potential point of confusion: historical records sometimes list multiple individuals with the same name. The provided source material initially contained conflicting biographical details, some pertaining to a Melchior Fritsch who lived much earlier (e.g., obtaining a law degree in 1661 and dying in 1701) and was involved in academia and theology. This is clearly a different individual from the 19th-century Austrian painter (1826-1889) who taught Olga Wisinger-Florian. Such conflations can occur in databases and require careful disentanglement by historians. For the purpose of this art historical discussion, we are firmly focused on the painter.

Similarly, a list of "contemporaries" provided in the source material included late 20th and 21st-century artists like Haim Steinbach, Sherrie Levine, Robert Gober, and Jeff Koons. These artists belong to entirely different generations and artistic movements (primarily Postmodernism and Conceptual Art) and are not contemporaries of the 19th-century painter Melchior Fritsch. This highlights the importance of critically evaluating source data.

Legacy and Conclusion

Melchior Fritsch's legacy is primarily that of a dedicated painter of Austrian landscapes and an influential teacher who contributed to the development of at least one major figure in Austrian Mood Impressionism, Olga Wisinger-Florian. His works, such as Alpensee and Bauernhof (in den Alpen), reflect the prevailing interest in Alpine and rural scenery in 19th-century Austrian art.

While he may not have been an avant-garde revolutionary, his role within the artistic ecosystem of his time was valuable. He represented a strand of solid, observational landscape painting and provided foundational training that enabled his students to pursue their own artistic paths, some of whom went on to embrace and shape newer artistic currents.

The study of artists like Melchior Fritsch enriches our understanding of the breadth and depth of artistic practice in a given period. It reminds us that art history is not solely composed of a few towering geniuses but is also built upon the contributions of many skilled practitioners and dedicated educators who collectively shape the cultural landscape. His life (1826-1889) and work offer a window into the evolving world of 19th-century Austrian art, a period of rich tradition and burgeoning innovation. Further research into regional archives and exhibition records might yet uncover more about his specific contributions and the full scope of his artistic production.