Michelangelo Cerquozzi stands as a significant figure in the vibrant landscape of Italian Baroque art. Born in Rome in 1602, he navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, leaving behind a legacy rich in dramatic battle scenes, intimate genre paintings, and pioneering still lifes. His skill in depicting combat earned him the evocative nickname "Michelangelo delle Battaglie" (Michelangelo of the Battles), distinguishing him within the bustling Roman art scene where he spent his entire career until his death in 1660.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Cerquozzi's entry into the world of art was facilitated by his family background. Born into a reasonably well-off family, with a jeweler father and a mother from a noble background, he received an art education from a young age. This early exposure laid the foundation for his future career. By the age of twelve, a pivotal moment arrived when he began his formal apprenticeship under the established history painter Giuseppe Cesari, also known as Cavaliere d'Arpino.

Training with Cesari, a prominent figure in late Mannerism transitioning towards the Baroque, would have provided Cerquozzi with a solid grounding in drawing, composition, and the grand tradition of historical painting. Although Cerquozzi would later diverge significantly in subject matter, this initial training under a master of large-scale narrative works undoubtedly honed his technical skills and understanding of pictorial construction, elements visible even in his smaller, more intimate canvases.

The Influence of the North: Embracing the Bambocciate

While his training was Italian, Cerquozzi's artistic identity was profoundly shaped by his interactions with artists from Northern Europe residing in Rome. He developed close ties with the Dutch and Flemish community, particularly with Pieter van Laer, a Dutch painter known in Italy as "Il Bamboccio" (meaning "ugly doll" or "puppet," possibly referring to his appearance). Van Laer was the central figure of a group of predominantly Northern artists who specialized in small paintings depicting the everyday lives of Rome's lower classes – peasants, artisans, gamblers, and street vendors.

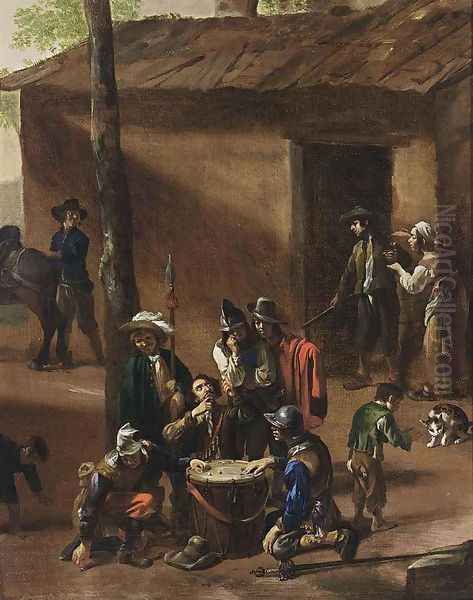

These paintings, known as bambocciate, were characterized by their realism, often earthy humor, and focus on scenes that contrasted sharply with the grand religious and mythological themes favored by the official art establishment. Cerquozzi embraced this genre wholeheartedly, becoming one of its most significant Italian exponents. His association with van Laer and others in this circle, like the painter Jan Miel, was crucial. It not only influenced his style and choice of subject matter but also helped him gain recognition and find patrons within Rome's diverse artistic milieu.

Cerquozzi's bambocciate captured the bustling, unvarnished reality of Roman street life. He depicted market scenes, tavern brawls, soldiers gambling, and peasants resting with an eye for detail and a sympathetic, though unsentimental, perspective. While initially criticized by some Italian art theorists who championed idealized beauty and noble subjects, the bambocciate proved popular with collectors who appreciated their lively naturalism and glimpse into ordinary existence. Cerquozzi excelled in rendering the textures of rough clothing, the play of light on cobblestone streets, and the expressive gestures of his figures.

Michelangelo of the Battles

Despite his success with genre scenes, Cerquozzi's most enduring fame, reflected in his nickname, came from his battle paintings. "Michelangelo delle Battaglie" was not merely a label; it signified his mastery in capturing the chaos, energy, and brutality of combat. His battle scenes are distinct from the often-static, formalized depictions of earlier periods. Cerquozzi infused them with Baroque dynamism and a heightened sense of realism.

His canvases often feature swirling masses of soldiers, cavalry charges, the smoke of musket fire, and the intense drama of hand-to-hand combat. He paid close attention to the details of military attire, weaponry, and the powerful musculature of horses caught in motion. The compositions are typically dynamic, using diagonal lines and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow (chiaroscuro, likely influenced by the works of Caravaggio) to heighten the sense of conflict and movement. These works showcased his pursuit of naturalism, aiming to convey the visceral experience of battle rather than just a historical record.

The popularity of his battle scenes reflects a contemporary fascination with military themes, possibly fueled by the ongoing conflicts across Europe during the 17th century. Patrons appreciated the vigor and dramatic intensity Cerquozzi brought to the genre. While specific attributions can sometimes be challenging, as many anonymous battle scenes from the period exist, his known works in this area solidify his reputation as a leading specialist.

A Pioneer in Still Life Painting

Beyond battles and street scenes, Cerquozzi made significant contributions to the genre of still life painting. He is considered by some art historians to be an innovator, particularly associated with a style described as "dal natural" – still life from nature. This approach often involved placing arrangements of fruits and sometimes flowers within landscape settings, emphasizing natural light and an outdoor ambiance.

His still lifes frequently feature arrangements of grapes, apples, figs, pomegranates, and other fruits, often depicted with a convincing realism and attention to texture and surface detail. The influence of Caravaggio's naturalism is evident here too, particularly in the handling of light to model forms and create a sense of tangible presence. By integrating the still life elements into rustic, pastoral backgrounds, Cerquozzi created a distinct, almost idyllic mood, moving beyond simple tabletop arrangements to evoke a connection with the natural world. This approach helped elevate the status of still life painting in Rome during the Baroque period.

His works in this genre, such as compositions focusing on seasonal fruits, demonstrate his versatility and his keen observational skills. The rich colours and tactile quality of the fruits, often set against darker foliage or a glimpse of sky, showcase his ability to render different textures and capture the effects of light with sensitivity.

Collaborations and Artistic Connections in Rome

Cerquozzi's career flourished within the collaborative and competitive environment of Baroque Rome. His most significant and long-lasting collaboration was with the architectural painter Viviano Codazzi. Originally from Bergamo but active in Naples before settling in Rome, Codazzi specialized in painting architectural settings, ruins, and perspective views (vedute). For approximately thirteen years, until Cerquozzi's death, the two artists frequently worked together.

In these joint works, Codazzi would typically paint the architectural or landscape background, often depicting classical ruins or imaginary cityscapes, while Cerquozzi would add the figures – soldiers, common folk, or mythological characters – animating the scene. This type of collaboration between specialists was common in the 17th century, allowing artists to combine their strengths and produce works efficiently for the market. Their partnership proved highly successful, resulting in numerous paintings that blended Codazzi's skillful rendering of space and structure with Cerquozzi's lively figures.

Beyond Codazzi, Cerquozzi maintained connections with a wide circle of artists in Rome. He interacted with prominent Italian painters such as the great Baroque master Pietro da Cortona, as well as Domenico Viola and Giacinto Brandi. These interactions involved not just potential artistic influence but also social connections within the Roman art world. He also kept ties with Northern artists beyond van Laer, including Paulus Bor (sometimes referred to as Paul Borghese) and Cornelis Bramer, indicating his integration into the international artistic community present in the city. Another documented connection is with Giovanni Battista Verrocchio (identified as Giovan Battista di Agostino, distinct from the Renaissance master), who served as a witness for Cerquozzi's will and inherited some items, suggesting a close personal relationship.

Spanish Affinities

An interesting aspect of Cerquozzi's life and career was his noted affinity for Spanish culture and people. Art historical sources suggest this connection may have stemmed from his youth when he received favour or patronage from a bishop associated with the Spanish embassy in Rome. This early support seems to have fostered a lasting positive sentiment.

This pro-Spanish leaning reportedly manifested in his personal habits, with accounts mentioning that he often chose to dress in Spanish attire. This personal preference might also subtly inform some of his works, perhaps in the depiction of certain character types or themes, although his primary subject matter remained rooted in Roman life and generic battle scenes. His connections, possibly maintained through the Spanish embassy, also helped his works gain visibility and influence within Spanish art circles, extending his reputation beyond Italy.

Representative Works and Their Locations

Cerquozzi's diverse output is represented by several key works, although many reside in private collections, making them less accessible to the public. Among his most famous paintings is the Rebellion of Masaniello. This large and dramatic canvas depicts the popular uprising led by Tommaso Aniello (Masaniello) against Habsburg rule in Naples in 1647. It showcases Cerquozzi's skill in handling complex multi-figure compositions and capturing intense historical drama. This significant work is housed in the Spada Gallery in Rome.

Other characteristic works include genre scenes like Soldiers Playing Dice and Soldiers and Card Players, which exemplify his bambocciate style, focusing on the activities of common soldiers and everyday life in Rome. Similar themes are explored in works titled Street Scene in Rome. These paintings are often found in private collections.

His skill in still life is evident in works often descriptively titled, focusing on arrangements of fruit within natural settings, sometimes referred to under concepts like The Reality of Light in the Light of Caravaggio, highlighting their stylistic lineage. A series depicting the Four Seasons, possibly featuring allegorical figures like Flora (Spring) and Ceres (Summer), also survives, likely in private hands.

Landscapes, sometimes produced in collaboration with Codazzi or independently, include works like By the Lake of Marindol (dated 1650-1660), also in a private collection. Institutional holdings include the Kassel Museum (Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister) in Germany, which owns a Garden party in Rome, and the Uffizi Gallery in Florence (not Naples, as sometimes mistakenly cited), which holds a Wooded landscape with hunters resting. These examples demonstrate the range of his subjects and the distribution of his surviving works across various European collections.

Artistic Style and Evolution

Cerquozzi's artistic style evolved throughout his career, though it remained largely anchored in the naturalistic tendencies prevalent in the early Baroque. His initial works show a clear debt to the realism and dramatic lighting associated with Caravaggio and his followers (the Caravaggisti). This is visible in the strong contrasts of light and shadow, the unidealized depiction of figures, and the focus on tangible reality, whether in genre scenes or still lifes.

As his career progressed, particularly in his later works, Cerquozzi absorbed more elements of the High Baroque style. While retaining his commitment to naturalistic detail, his compositions could become more complex and decorative, and his handling of paint sometimes looser and more painterly. The dramatic intensity remained, especially in battle scenes, but it might be expressed through more elaborate arrangements and a richer colour palette, aligning with the broader trends in Roman painting led by figures like Pietro da Cortona. However, he never fully abandoned the grounded realism that characterized his bambocciate and still lifes. His unique position lies in his ability to bridge the gap between the low-life genre scenes popularized by Northern artists and the more dramatic, large-scale demands of Italian Baroque taste.

Students, Legacy, and Historical Reception

Michelangelo Cerquozzi was an active participant in the Roman art scene not only as a painter but also as a master who took on students. Among those documented as having studied with him are Francesco del Conte, who notably inherited Cerquozzi's unfinished paintings upon his master's death, suggesting a close working relationship. Other known pupils include Matteo Bonicelli and Giovanni Francesco Gerardi. Through these students, his style and techniques were disseminated further.

Historically, Cerquozzi's reception has been somewhat mixed, though his importance is now well-recognized. During his lifetime and shortly after, his bambocciate were popular with certain collectors but criticized by proponents of academic art theory, like Giovanni Pietro Bellori, who favored idealized subjects and classical principles. They saw the focus on low-life themes as lacking decorum and intellectual substance. However, the enduring appeal of his works, particularly the battle scenes and still lifes, ensured his continued reputation.

Over time, art historical re-evaluation has highlighted his significant contributions. He is recognized for his role in popularizing genre painting in Italy, his innovative approach to still life, and his mastery of dynamic battle compositions. While sometimes criticized in the past for an overabundance of detail that could detract from compositional unity, his keen powers of observation, his technical skill, and his ability to capture the vitality of everyday life and the intensity of conflict are now widely appreciated. He is seen as a versatile and influential figure within the complex tapestry of Roman Baroque art.

Later Life and Success

Cerquozzi's talent and connections brought him considerable success during his lifetime. By his later years, he was living a prosperous life in Rome. Contemporary accounts and documents indicate that he maintained multiple studios and employed assistants to help manage his prolific output and meet the demands of his patrons.

His paintings commanded high prices on the Roman art market. Works could sell for substantial sums, reportedly between three hundred and four hundred scudi, a significant amount for the period, testifying to his established reputation and the desirability of his art among collectors, who included Italian nobility and prominent figures associated with foreign embassies, notably the Spanish. This financial success allowed him a comfortable existence and confirmed his status as a leading painter in one of Europe's most important artistic centers. He remained active in Rome until his death on April 6, 1660.

Conclusion: A Multifaceted Baroque Master

Michelangelo Cerquozzi emerges from the historical record as a painter of remarkable versatility and skill. From the gritty realism of Roman street life in his bambocciate to the dynamic chaos of his battle scenes and the lush naturalism of his still lifes, he navigated multiple genres with confidence. His nickname, "Michelangelo delle Battaglie," highlights one facet of his talent, but his contributions to genre and still life painting were equally significant, bridging Italian traditions with Northern European influences.

Working alongside collaborators like Viviano Codazzi and interacting with a wide circle of artists including Pieter van Laer, Pietro da Cortona, and Giuseppe Cesari, Cerquozzi carved out a distinct niche in the competitive Roman art world. Though subject to the critical debates of his time, his work found favour with patrons and has earned him a lasting place in the history of Baroque art. His paintings offer a vivid window into the diverse realities and artistic currents of 17th-century Rome, rendered with technical prowess and a keen eye for the drama of both conflict and everyday existence.