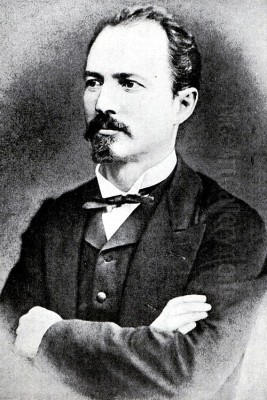

Nicolae Grigorescu stands as a foundational figure in the history of Romanian art, celebrated as one of the pioneers who guided painting in his homeland towards modernity. Born in 1838 and passing away in 1907, his life spanned a period of significant cultural and political transformation in Romania. Grigorescu's artistic journey took him from painting religious icons in rural monasteries to the heart of the Parisian art world and the front lines of the Romanian War of Independence. His legacy is defined by his luminous landscapes, empathetic depictions of peasant life, and his crucial role in introducing and adapting contemporary European art movements, particularly the Barbizon School and Impressionism, to a Romanian context. His work remains deeply cherished, embodying a particular vision of the Romanian soul and landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Nicolae Grigorescu was born in Pitaru, a village in Wallachia (now part of Dâmbovița County, Romania), in 1838. Hailing from a peasant family, his early life was marked by modesty. Following the death of his father, the family relocated to Bucharest, the bustling capital city. It was here, amidst the city's vibrant, albeit developing, cultural scene, that young Nicolae's artistic talents began to surface. His formal artistic training commenced relatively early.

Around 1843, he began an apprenticeship in the workshop of Anton Chladek, a painter of Czech origin who had settled in Bucharest. Under Chladek's guidance, Grigorescu learned the craft of painting, initially focusing on the creation of icons and church murals, a common path for aspiring artists in the region at that time. This early training instilled in him a strong foundation in drawing and composition, rooted in the Byzantine traditions prevalent in Orthodox church art, but also exposed him to the Westernizing influences Chladek brought.

His skills quickly developed, and he gained commissions to decorate several churches and monasteries. Notable early works include icons painted for the church in Băicoi and the Căldărușani Monastery. He also undertook significant mural projects, such as those for the Zamfir Monastery (around 1856-1857) and, most significantly, the Agapia Monastery (completed around 1858-1861). The Agapia murals, in particular, are often cited as a high point of his early career, showcasing a departure from strict Byzantine canons towards a more realistic and humanized portrayal of religious figures, hinting at the burgeoning influence of Western academic styles.

Alongside his religious commissions, Grigorescu explored historical themes, a genre gaining popularity in the context of rising national consciousness in the Romanian principalities. In 1856, he painted Mihai Viteazul scăpând stindardul (Michael the Brave Dropping the Standard), depicting a legendary moment featuring the heroic Wallachian prince. This work demonstrated his ambition to engage with grand national narratives, aligning himself with the Romantic ideals prevalent across Europe. These formative years established Grigorescu as a talented and versatile young artist within the Romanian artistic landscape.

The Parisian Transformation: Barbizon and Beyond

A pivotal moment in Grigorescu's career arrived in 1861 when, thanks to the support of Mihail Kogălniceanu, a prominent politician and cultural figure, he was awarded a scholarship to study art in Paris. This move immersed him in the dynamic and revolutionary art scene of the French capital, which would profoundly shape his artistic vision and technique. Paris was the undisputed center of the art world, a crucible of competing styles and emerging movements.

Initially, Grigorescu enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts and briefly studied in the studio of Sébastien Cornu, a painter known for his academic approach. It was in Cornu's studio that he reportedly met fellow student Pierre-Auguste Renoir, marking an early connection with a future giant of Impressionism. However, Grigorescu soon found the rigid academicism of the official institutions stifling. He was drawn instead to the revolutionary ideas circulating outside the Salon system.

His true artistic awakening in France came through his encounter with the Barbizon School. This group of painters, including artists like Jean-François Millet, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny, had rejected the idealized landscapes of Neoclassicism and Romanticism. They advocated for painting directly from nature (en plein air) in the Forest of Fontainebleau near the village of Barbizon, focusing on realistic depictions of rural landscapes and peasant life. Grigorescu spent considerable time in Barbizon, absorbing their philosophy and techniques.

The Barbizon emphasis on capturing the effects of natural light, the textures of the landscape, and the unvarnished reality of rural existence resonated deeply with Grigorescu. He began painting outdoors, developing a lighter palette and a looser brushstroke to capture the fleeting atmospheric conditions. He formed connections with artists associated with or influenced by the Barbizon ethos, including Millet, whose depictions of peasant dignity likely struck a chord, as well as Camille Pissarro and the great Realist Gustave Courbet.

During his time in France, Grigorescu produced numerous works reflecting this new direction. Paintings like Tânără ţigancă (Young Gypsy Girl), exhibited with success at the Paris Salon of 1868, showcase his growing interest in capturing individual character and his evolving, more naturalistic style. His French period was crucial; he assimilated the lessons of Barbizon naturalism and was exposed to the nascent Impressionist movement, elements he would later synthesize into his uniquely Romanian artistic language upon his return home. He participated in the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1867, gaining international exposure.

Chronicler of a Nation: The War of Independence

Grigorescu's connection to his homeland remained strong despite his time abroad. A significant chapter in his life and work unfolded during the Romanian War of Independence (1877-1878), part of the larger Russo-Turkish War, which led to Romania gaining full independence from the Ottoman Empire. Driven by patriotic sentiment, Grigorescu volunteered to accompany the Romanian army as a frontline painter, tasked with documenting the campaign.

This experience immersed him directly in the realities of war – the hardships of the soldiers, the tension of battle, and the dramatic landscapes of the conflict zones, primarily in Bulgaria. He created numerous drawings, sketches, and oil paintings capturing scenes from the front. These works stand apart from his more idyllic rural scenes, imbued with a sense of immediacy and historical weight. He depicted military encampments, convoys, portraits of soldiers, and battle scenes.

Among the most famous works resulting from this period is Atacul de la Smârdan (The Attack at Smârdan), a dynamic and dramatic composition depicting a key battle involving Romanian troops. Unlike the often-glorified and staged battle paintings of academic tradition, Grigorescu's work, while patriotic, often conveyed the human element and the gritty atmosphere of the conflict. His sketches, such as those depicting Turkish Prisoners on the March, possess a raw, documentary quality.

His role as a war artist was significant not only for its artistic output but also for its contribution to the national narrative of independence. His works provided visual testimony to the struggle and sacrifices made, resonating deeply with the Romanian public. This period added another dimension to Grigorescu's oeuvre, demonstrating his ability to engage with historical events and national themes with authenticity and artistic power, further solidifying his position as a painter deeply connected to the Romanian experience.

Return to Romania: The Câmpina Years and Rural Idylls

After his experiences in France and on the battlefield, Grigorescu eventually returned to Romania, spending time traveling throughout the country and also returning periodically to France and Italy. However, from the 1880s onwards, he increasingly sought refuge and inspiration in the Romanian countryside. He eventually settled in Câmpina, a town nestled in the Prahova Valley near the Carpathian Mountains. This region, with its rolling hills, picturesque villages, and pastoral way of life, became the primary subject of his mature work.

The Câmpina years represent the quintessential Grigorescu period for many admirers. He dedicated himself almost entirely to capturing the beauty of the Romanian landscape and the lives of its peasant inhabitants. His house and studio in Câmpina (now a memorial museum) became his sanctuary, from where he explored the surrounding countryside, painting en plein air whenever possible. His focus shifted definitively towards themes that celebrated the perceived harmony between humanity and nature in rural Romania.

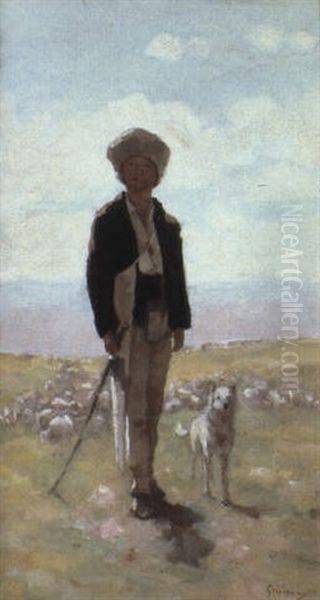

His canvases from this era are populated with iconic Romanian imagery: shepherds tending their flocks, peasant girls in traditional attire, rustic carts pulled by oxen, dusty country roads winding through sunlit fields, and views of the Carpathian foothills. Works like Car cu boi (Ox Cart) became emblematic, representing not just a mode of transport but a symbol of the timeless, enduring rhythm of rural life. Other notable works include Ţărancă din Muscel (A Peasant Woman from Muscel), Turma de oi (Flock of Sheep), Ţărănci torcând (Peasant Women Spinning/with Distaff), and numerous landscapes simply titled after the locations they depicted, such as Bucegi.

Grigorescu's portrayal of peasant life during this period is often characterized as idyllic and optimistic. He focused on the picturesque aspects, emphasizing the simple beauty, dignity, and resilience of rural folk, often bathed in warm, golden light. While some later critics pointed out a tendency towards romanticization, arguing that he glossed over the hardships of peasant existence, his works resonated powerfully with a national audience seeking positive representations of Romanian identity and tradition. The Câmpina period cemented Grigorescu's reputation as the preeminent painter of the Romanian countryside.

Artistic Style and Technique

Nicolae Grigorescu's artistic style is a unique synthesis of the influences he absorbed throughout his career, adapted to his personal sensibility and Romanian subjects. While often associated with Impressionism, his style is perhaps more accurately described as a blend of Barbizon naturalism with Impressionist techniques, filtered through a fundamentally Romantic temperament. He was not a doctrinaire follower of any single movement but rather selected and combined elements that suited his expressive goals.

A defining characteristic of his work is the masterful handling of light and atmosphere. Influenced by the Barbizon painters' practice of en plein air painting, Grigorescu excelled at capturing the specific quality of Romanian sunlight – often warm, hazy, and enveloping. He used a bright, luminous palette, employing broken brushwork reminiscent of the Impressionists to convey the vibration of light and air. However, unlike French Impressionists such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro who sought to dissolve form in light, Grigorescu generally maintained a stronger sense of structure and drawing, a legacy perhaps of his earlier academic and religious training.

His brushwork is typically fluid, energetic, and expressive, giving his paintings a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. He often applied paint in visible strokes, allowing the texture of the paint itself to contribute to the overall effect. This technique was particularly effective in rendering the textures of nature – dusty roads, sun-scorched fields, the rough wool of sheep, or the foliage of trees.

In terms of subject matter, his focus on rural landscapes and peasant life aligns him with the Barbizon School and Realist tendencies. However, his treatment of these subjects often carries a lyrical, poetic quality that leans towards Romanticism. He emphasized harmony, tranquility, and a sense of timelessness in his depictions of the countryside. While he painted portraits, still lifes, and interiors, particularly earlier in his career (e.g., Fata cu basma albă - Girl with White Veil, Ţărancă cosând la fereastră - Peasant Woman Sewing by the Window), landscape and rural genre scenes dominate his mature oeuvre.

Grigorescu consciously rejected the constraints of strict academicism, favoring direct observation and personal interpretation. His process often involved making numerous sketches and studies outdoors, which he might later develop into finished paintings in his studio. His style was innovative within the Romanian context, breaking away from the darker palettes and more rigid compositions of his predecessors and contemporaries like Theodor Aman, paving the way for modern Romanian painting.

Contemporaries, Influence, and Legacy

Nicolae Grigorescu did not work in isolation. His career intersected with numerous important figures in both Romanian and European art and culture. In Paris, his encounters with Renoir, Pissarro, Courbet, and the spirit of Millet and the Barbizon group were formative. These interactions placed him at the confluence of major artistic currents – Realism, the Barbizon School, and emerging Impressionism.

Back in Romania, he was a leading figure in a generation striving to establish a modern national art. He was a contemporary of Theodor Aman, another foundational figure who, unlike Grigorescu, leaned more towards academicism and historical painting but shared the goal of developing Romanian art. Grigorescu's approach, however, proved more influential on subsequent generations seeking freer expression. He maintained connections with cultural figures like the writer Alexandru Vlahuță, who became a close friend and biographer.

While perhaps not having formal students in the traditional sense of running a large atelier, Grigorescu's work served as a powerful example and inspiration. His brother, George Grigorescu, assisted him in some early church decoration projects. Painters like Ion Andreescu, a major Romanian artist often grouped with Grigorescu and Aman as the triumvirate of modern Romanian painting, shared a similar interest in landscape and Impressionist techniques, though Andreescu's work possesses a distinct, more melancholic sensibility. Sava Albescu was another painter associated with his circle. Grigorescu also held teaching positions at art schools in Bucharest, contributing to the education of younger artists.

Grigorescu's primary legacy lies in his role as a bridge between European modernism and Romanian artistic identity. He successfully introduced the principles of en plein air painting, Barbizon naturalism, and Impressionist light and color into Romanian art, adapting them to local subjects and sensibilities. He essentially created the archetype of the Romanian landscape painting, influencing countless artists who followed. His depictions of peasant life, while sometimes idealized, became powerful symbols of national identity and cultural continuity.

He died in Câmpina in 1907, reportedly leaving a painting unfinished on his easel, a testament to his lifelong dedication to his craft. His influence was immediate and lasting, shaping the course of Romanian painting for decades.

Critical Reception Through Time

Nicolae Grigorescu has consistently been held in high esteem within Romanian art history, although the specific focus of critical appreciation has evolved. During his lifetime and in the decades following his death, he was celebrated primarily as the national painter, the artist who best captured the essence of the Romanian land and its people. His technical skill, particularly his mastery of light and color, and his ability to convey a sense of poetic harmony were widely praised.

Critics lauded his departure from the perceived darkness and rigidity of earlier Romanian painting, hailing his work as fresh, modern, and authentically Romanian. His murals at the Agapia Monastery were recognized early on as masterpieces demonstrating his skill in composition and graceful rendering of figures. His war paintings were valued for their patriotic significance and documentary quality. His later landscapes and rural scenes, especially those from the Câmpina period, became immensely popular and were seen as embodying the national soul.

Comparisons were often made with French Impressionism, with critics acknowledging his absorption of Impressionist techniques while emphasizing the unique Romanian character of his work. He was seen as successfully balancing innovation with a respect for tradition, creating a style that was both modern and accessible. Figures like Alexandru Vlahuță wrote glowingly about his life and art, contributing to his heroic stature.

However, later in the 20th century and beyond, while his foundational importance remained undisputed, some critical re-evaluations emerged. Certain critics, particularly those influenced by social realism or later modernist aesthetics, questioned the perceived idealization in his depictions of peasant life. They argued that his focus on picturesque beauty sometimes overlooked the social hardships and economic struggles faced by the Romanian peasantry during that era, suggesting his vision was overly romanticized or even sentimental.

Despite these nuanced critiques, Grigorescu's overall reputation remains overwhelmingly positive. He is universally acknowledged as a pivotal figure who modernized Romanian art. His ability to synthesize European trends with local themes, his technical brilliance in capturing light and atmosphere, and the sheer beauty and emotional resonance of his best works ensure his enduring place as one of Romania's most beloved and significant artists. His paintings continue to be highly sought after and are central exhibits in major Romanian museums.

Conclusion

Nicolae Grigorescu's contribution to Romanian art is immense and multifaceted. As a pioneer, he broke from the constraints of provincial academicism, opening Romanian painting to the vital currents of 19th-century European modernism. His engagement with the Barbizon School and Impressionism provided a new language for depicting the Romanian landscape and its people, emphasizing light, atmosphere, and direct observation. From his early religious murals to his dramatic war sketches and his iconic Câmpina landscapes, his work consistently demonstrated technical mastery and a deep connection to his subject matter.

While his vision of rural life might be viewed through a romantic lens, it captured an essential aspect of the Romanian cultural identity and resonated profoundly with his contemporaries and subsequent generations. He remains celebrated not just as an innovator and a master of light, but as the painter who, perhaps more than any other, defined the visual representation of the Romanian countryside. His legacy endures in the countless artists he influenced and in the enduring affection his luminous and evocative paintings inspire. Nicolae Grigorescu is, undeniably, a cornerstone of Romanian national culture.