Nicolas Van Veerendael stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the rich tapestry of 17th-century Flemish Baroque painting. Active primarily in Antwerp, he carved a niche for himself as a specialist in still life, particularly renowned for his exquisite floral compositions and profound Vanitas paintings. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, vibrant yet controlled color palettes, and deep symbolic meaning, offers a fascinating window into the artistic, cultural, and intellectual currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis in Antwerp

Born in Antwerp in 1640, Nicolas Van Veerendael was immersed in the world of art from a young age. His father, Willem Van Veerendael (also recorded as Guillaume), was himself a painter, providing Nicolas with his initial artistic training. This familial introduction to the craft was common in an era where artistic skills were often passed down through generations, and guilds played a crucial role in regulating and fostering artistic talent.

Antwerp, during Van Veerendael's formative years, was a city still reverberating with the artistic energy of giants like Peter Paul Rubens and Anthony van Dyck, though its golden age as the primary economic hub of Northern Europe had passed. Nevertheless, it remained a vital center for art production, particularly for specialized genres like still life. The city's Guild of Saint Luke, the professional organization for painters and other artists, was a prestigious institution, and membership was essential for any artist wishing to practice independently. Van Veerendael was officially registered as a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in 1657, at the remarkably young age of seventeen. This early acceptance signifies a precocious talent and a solid foundation in the technical aspects of painting.

Influences and the Antwerp Still Life Tradition

Upon entering the Guild, Van Veerendael's artistic development was further shaped by the prevailing trends and leading figures in Antwerp's still-life scene. Two artists, in particular, are consistently cited as major influences: Daniel Seghers and Jan Davidsz. de Heem.

Daniel Seghers (1590-1661), a Jesuit lay brother, was celebrated for his flower cartouches – religious scenes or portraits encircled by meticulously rendered garlands of flowers. Seghers' work was characterized by its luminous, almost enamel-like finish, precise botanical accuracy, and delicate coloration. Van Veerendael's early works clearly echo Seghers' influence in their bright, pure, and strong colors, as well as the careful, almost reverent depiction of individual blooms.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684), who worked in both Utrecht and Antwerp, was a master of the opulent "pronkstilleven" (ostentatious still life). His compositions were often larger, more complex, and featured a lavish array of objects – flowers, fruits, silverware, and rich textiles – arranged in dynamic, asymmetrical designs. De Heem's influence on Van Veerendael is evident in the latter's move towards more open and elaborate compositions, particularly in his mid-career, and a richer, more varied palette. The interplay of light and texture in De Heem's work also seems to have inspired Van Veerendael.

The still-life tradition in Flanders was already well-established by the time Van Veerendael began his career. Artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder (1568-1625) had pioneered detailed floral still lifes, often imbued with symbolic meaning. Osias Beert (c. 1580-1623/24) and Clara Peeters (1594-c. 1657) were other early proponents of the genre, laying the groundwork for the sophisticated developments of the mid-17th century.

Stylistic Evolution: From Clarity to Complexity

Van Veerendael's artistic journey can be broadly divided into distinct stylistic phases, reflecting his absorption of influences and his own developing artistic voice.

His early period, roughly from his entry into the guild until the late 1660s, shows a strong affinity with the clarity and bright palette of Daniel Seghers. Works from this time often feature carefully arranged bouquets, where each flower is rendered with precision. The colors are luminous and pure, and the overall effect is one of delicate beauty. The lighting is often even, highlighting the individual forms of the flowers.

During his mid-career, from approximately 1670 to 1679, Van Veerendael's style matured and became more complex. He began to create denser floral arrangements, and his compositions became more open and dynamic, reflecting the influence of Jan Davidsz. de Heem. The dialogue between elements within the painting grew richer, with a greater emphasis on texture and the interplay of light and shadow. His brushwork, while still precise, may have gained a degree of fluidity during this period.

The late works of Van Veerendael, from 1680 until his death in 1691, are characterized by an even freer technique and a richer exploration of floral themes. Some scholars note a shift towards more agitated petal rendering and a less glossy finish compared to his earlier, Seghers-influenced pieces. This later period demonstrates a painter confident in his abilities, perhaps experimenting more with texture and the expressive potential of his medium.

The Language of Flowers: Floral Still Lifes

Floral still lifes formed a significant portion of Nicolas Van Veerendael's oeuvre. In the 17th century, flowers were not merely decorative; they were laden with symbolic meaning. The tulip, for instance, could symbolize wealth and speculation (especially after "Tulip Mania"), but also transience due to its fleeting bloom. Roses often represented love or, in a religious context, the Virgin Mary. Lilies could signify purity, while sunflowers might allude to devotion or royalty.

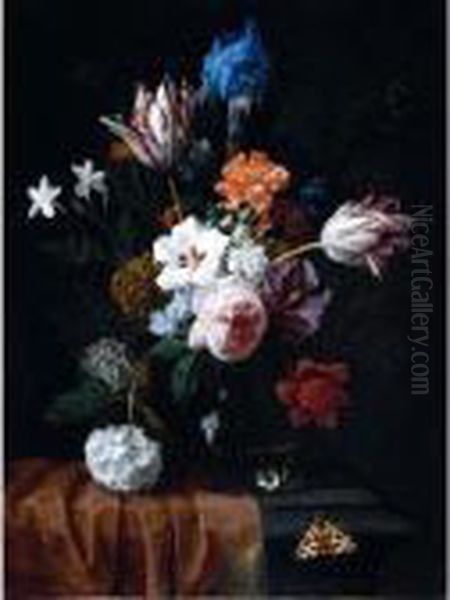

Van Veerendael's flower paintings are celebrated for their botanical accuracy and exquisite detail. He often included a variety of blooms in a single composition, showcasing his skill in rendering different textures and colors. A work like his Still Life with Flowers in a Glass Vase exemplifies this mastery. Here, a profusion of tulips, roses, carnations, and other flowers bursts from a simple glass vase. Each petal is delicately rendered, and the subtle play of light on the surfaces of the flowers and the vase creates a sense of depth and realism.

Insects such as butterflies, caterpillars, and beetles frequently appear in his floral arrangements. These too carried symbolic weight: butterflies could represent resurrection or the soul, while caterpillars and flies might allude to decay and the brevity of life. Their inclusion added another layer of meaning to the paintings, inviting viewers to contemplate the interconnectedness of beauty, life, and decay.

Memento Mori: The Vanitas Paintings

Beyond floral arrangements, Van Veerendael was a notable practitioner of the Vanitas still life. The Vanitas genre, particularly popular in the Netherlands and Flanders during the 17th century, aimed to remind viewers of the transience of earthly life and the vanity of worldly pleasures. The term "Vanitas" itself comes from the Book of Ecclesiastes: "Vanity of vanities, all is vanity."

These paintings typically feature a collection of symbolic objects. Skulls are the most direct memento mori (reminder of death). Books and scientific instruments might symbolize the limits of human knowledge in the face of eternity. Hourglasses, snuffed-out candles, or watches point to the passage of time. Musical instruments and playing cards could represent fleeting pleasures. Wilting flowers and decaying fruit underscore the theme of impermanence.

Van Veerendael's Vanitas paintings, such as the work often titled Vanité (Vanity), which typically includes a skull, books, and perhaps a snuffed candle or wilting flowers, are powerful meditations on these themes. He skillfully arranged these symbolic elements to create compositions that were both aesthetically pleasing and intellectually stimulating. The juxtaposition of a skull, representing death, with books, symbolizing knowledge or perhaps the futility of worldly learning, invites profound contemplation.

The historical context of 17th-century Antwerp, a city in the Spanish Netherlands (a Catholic territory), is crucial for understanding these works. While the Vanitas theme was strong in the Protestant Dutch Republic, it also resonated in Catholic Flanders, where Counter-Reformation piety emphasized reflection on mortality and the importance of spiritual salvation over worldly pursuits. Van Veerendael's Vanitas paintings thus engaged with deep philosophical and religious concerns prevalent in his society, exploring themes of hope and despair, the ephemeral nature of existence, and the promise of an afterlife.

Collaborations and Artistic Circles

Collaboration was a common practice among Antwerp painters in the 17th century, allowing artists to combine their specialized skills. Nicolas Van Veerendael participated in this tradition, often painting the floral elements in works by other artists who specialized in figures or different types of still life.

He is known to have collaborated with several prominent contemporaries. His connection with Jan Davidsz. de Heem was not just one of influence but also of direct partnership on occasion; one such example is a Bouquet of Flowers with a Crucifix and a Shell, where their combined talents are evident. He also worked with figure painters like David Teniers the Younger (1610-1690), known for his peasant scenes and genre paintings, and Gonzales Coques (1614/18-1684), who specialized in elegant group portraits.

Other collaborators included Erasmus Quellinus II (1607-1678), a history and portrait painter who had worked with Rubens; Jan Boeckhorst (c. 1604-1668), another painter from Rubens' circle; and Carstian Luyckx (1623 – c. 1675), a fellow still-life painter. These collaborations highlight Van Veerendael's respected position within the Antwerp artistic community and the demand for his specialized skill in rendering flowers. The ability to seamlessly integrate his work with that of others speaks to his versatility and professionalism.

The broader artistic landscape of Antwerp at the time included other notable still-life painters such as Frans Snyders (1579-1657) and Adriaen van Utrecht (1599-1652), who were masters of large-scale market scenes and hunting still lifes, often incorporating abundant displays of game, fruit, and vegetables. Jan Fyt (1611-1661) was another contemporary renowned for his hunting scenes and animal paintings, which often included still-life elements. While Van Veerendael's focus was more on intimate floral and Vanitas pieces, he operated within this vibrant and diverse still-life tradition. Even the towering figure of Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678), primarily a history and genre painter, contributed to the rich artistic output of Antwerp during this period.

Representative Works and Signature Style

Several key characteristics define Nicolas Van Veerendael's artistic signature. His meticulous attention to detail is paramount, whether in the delicate veining of a petal, the iridescent sheen on an insect's wing, or the reflective surface of a glass vase. His color palette, particularly in his floral works, is often vibrant yet harmonious, with a skillful balance of warm and cool tones.

His compositions, especially in his mature phase, often feature a low viewpoint and clever asymmetrical arrangements, typical of Baroque dynamism. There is a sense of controlled abundance in his bouquets, where flowers seem to spill naturally from their containers, yet every element is precisely placed for maximum effect.

Among his notable works, beyond those already mentioned:

Still Life with Flowers in a Glass Vase: A quintessential example of his floral painting, showcasing his ability to capture the beauty and fragility of blooms, often accompanied by symbolic insects.

Vanité (Skull and Books): A powerful representation of the Vanitas theme, compelling viewers to reflect on mortality and the ephemeral nature of worldly pursuits. The careful rendering of the skull and the textures of aged books are typical of his skill.

Flora (or works with similar titles, sometimes featuring a crucifix): These paintings often combine religious symbolism with the beauty of flowers, perhaps alluding to themes of resurrection, purity, or the Virgin Mary. The work Bouquet of Flowers with a Crucifix and a Shell, a collaboration with De Heem, falls into this thematic category, blending devotional imagery with naturalistic depiction.

His paintings often possess a quiet, contemplative mood. Even in his most lavish floral arrangements, there is a sense of order and underlying seriousness, particularly when one considers the symbolic layers.

Historical Position and Enduring Legacy

Nicolas Van Veerendael occupies a respected place in the history of Flemish Baroque art, specifically within the still-life genre. He successfully navigated the artistic currents of his time, absorbing the influences of masters like Seghers and De Heem while developing his own distinct style. His technical proficiency was undeniable, and his ability to imbue his works with complex symbolic meaning contributed to their appeal.

While perhaps not as widely known today as some of his contemporaries like Rubens or Van Dyck, or even the most famous still-life specialists like De Heem or Willem Kalf (a Dutch contemporary), Van Veerendael's contributions are significant. He represents the high level of specialization and artistic quality that characterized the Antwerp school in the 17th century. His works are held in numerous museums and private collections, and they continue to be appreciated for their beauty, technical skill, and intellectual depth.

The enduring appeal of his paintings also lies in their universal themes. The beauty of flowers, the passage of time, and the contemplation of life and death are subjects that resonate across centuries. His Vanitas paintings, in particular, remain potent reminders of human mortality and the search for meaning, themes that are as relevant today as they were in the 17th century. The continued presence of his works in the art market, often achieving respectable prices at auction, attests to his lasting artistic value and the ongoing appreciation for his refined and thoughtful art.

Conclusion: A Master of Detail and Meaning

Nicolas Van Veerendael was more than just a painter of pretty flowers. He was a highly skilled artist who used the language of still life to explore profound themes of beauty, transience, and spirituality. His meticulous technique, his sensitivity to color and light, and his ability to weave complex symbolism into his compositions mark him as a master of his chosen genre. From his early, brightly lit bouquets to his more complex mature works and his deeply resonant Vanitas paintings, Van Veerendael left behind a body of work that continues to captivate and provoke thought. He remains an important figure for understanding the richness and diversity of Flemish Baroque art and the enduring power of still-life painting.