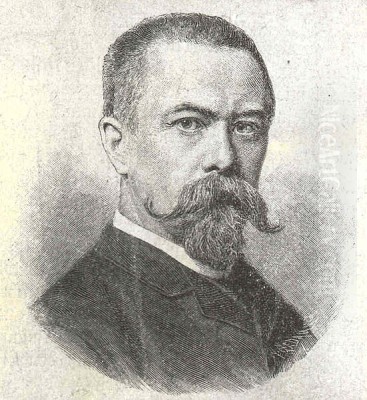

Otto Piltz (1846-1910) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in German art of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A painter renowned for his sensitive portrayals of rural life, domestic interiors, and the gentle human moments within them, Piltz carved a niche for himself within the broader currents of German Realism and the specific traditions of the Weimar School of Art. His work, characterized by meticulous detail, a warm palette, and an empathetic approach to his subjects, resonated with a public that appreciated both technical skill and sentimental narratives. This exploration delves into the life, artistic development, key works, and the cultural milieu of Otto Piltz, positioning him within the rich tapestry of his contemporaneous art world.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Weimar

Born on June 26, 1846, in Allstedt, a town in Thuringia, Germany, Otto Piltz's artistic journey began in a region rich with cultural history. His formative years as an artist were spent at the Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School (Großherzoglich-Sächsische Kunstschule Weimar). This institution, founded in 1860, was a crucible of artistic innovation and traditional training, attracting talent from across Germany and beyond. While specific details of his teachers are not always at the forefront of historical records, the ethos of the Weimar School during this period would have profoundly shaped his artistic outlook.

The Weimar School was known for its emphasis on realism, particularly in landscape and genre painting. Artists like Ferdinand Pauwels, who taught history painting, and landscape painters such as Theodor Hagen and Karl Buchholz, were influential figures associated with the school around the time Piltz would have been studying. The school fostered an environment where direct observation and faithful representation were highly valued, yet it also allowed for the infusion of personal sentiment and narrative, particularly in genre scenes. Piltz's inclination towards depicting everyday life, especially that of the peasantry and rural communities, found a supportive and stimulating environment in Weimar.

His early works began to exhibit the hallmarks that would define his career: a keen eye for detail, an ability to capture the nuances of human expression and interaction, and a preference for subjects that evoked a sense of nostalgia, simplicity, and the enduring values of hearth and home. The training in Weimar provided him with the technical proficiency in drawing and oil painting necessary to translate his observations and sentiments onto canvas with conviction.

The Weimarer Genremalerei and Piltz's Contribution

Otto Piltz became closely associated with what is known as the Weimarer Genremalerei, or Weimar Genre Painting. This particular strand of genre painting, flourishing in the latter half of the 19th century, focused on scenes of everyday life, often with a sentimental or anecdotal quality. These works were popular with the burgeoning middle class, who appreciated their relatability, their moral undertones, and their often idealized depictions of rural or historical life.

Piltz's contributions to this tradition were significant. His paintings often featured interiors – humble peasant cottages, cozy living rooms – where families gathered, individuals engaged in quiet tasks, or moments of gentle human connection unfolded. He was adept at rendering the textures of fabrics, the play of light on wooden surfaces, and the intimate atmosphere of these enclosed spaces. His figures, whether children at play, women engaged in needlework, or elderly folk in contemplation, were portrayed with dignity and a quiet realism that avoided overt melodrama.

During his Weimar period, his paintings were noted for their "sweet and sentimental" style, which garnered high praise. This characterization points to the emotional resonance of his work, which aimed to touch the viewer's heart as much as to please the eye. He was part of a cohort of artists in Weimar who contributed to this genre, including figures like Alexander Struys, Karl Gussow (though Gussow later moved towards a more academic, portrait-focused style), and Wilhelm Zimmer, each bringing their own nuances to the depiction of everyday life.

Travels and Broadening Horizons: Berlin and Munich

While Weimar provided a crucial foundation, Piltz, like many artists of his generation, sought to expand his horizons and engage with larger artistic centers. In 1886, he made the move to Berlin, then a rapidly growing metropolis and a vibrant hub of artistic activity. Berlin offered new opportunities for exhibitions, patronage, and interaction with a wider range of artistic trends, from the established academic styles to the emerging modernist movements.

His time in Berlin, though perhaps less defining than his Weimar or subsequent Munich periods in terms of stylistic shifts, would have exposed him to a more diverse art scene. The influence of painters like Adolph Menzel, with his meticulous historical realism and depictions of urban life, or Max Liebermann, a leading figure of German Impressionism (though Piltz's style remained distinct from Impressionism), would have been part of the artistic discourse.

After a few years in Berlin, Piltz relocated again in 1889, this time to Munich. The Bavarian capital was another major art center, particularly renowned for the Munich School, which emphasized painterly realism, often with a focus on genre scenes, portraiture, and historical subjects. Artists like Franz von Defregger, known for his depictions of Tyrolean peasant life and historical events, and Wilhelm Leibl, a master of unvarnished realism, were towering figures associated with Munich. Piltz would spend a significant portion of his later career in Munich, living there for nearly three decades until his death.

The Munich environment, with its strong tradition of genre painting and its appreciation for technical skill, likely proved congenial to Piltz. He continued to produce works that resonated with his established themes, finding a receptive audience for his carefully crafted and emotionally engaging scenes.

Artistic Style: Romanticism, Realism, and Sentimentalism

Otto Piltz's artistic style is a nuanced blend of several prevailing currents of 19th-century art. At its core, his work is rooted in Realism, with its commitment to depicting the world as observed. This is evident in his meticulous attention to detail, whether in the rendering of a peasant's worn clothing, the specific tools of a craftsman, or the humble furnishings of a rural dwelling. His figures are grounded and believable, their postures and activities drawn from life.

However, Piltz's Realism is often infused with elements of German Romanticism. This is not the dramatic, sublime Romanticism of Caspar David Friedrich, but rather a more intimate, Biedermeier-inflected Romanticism that valued domesticity, emotion, and the beauty of the everyday. His paintings frequently evoke a sense of nostalgia and a longing for a simpler, more harmonious way of life, often associated with the rural past. The "sweet and sentimental" quality noted by his contemporaries speaks to this Romantic sensibility, which aimed to stir the viewer's emotions and create a connection with the depicted scene.

The term Weimarer Genremalerei itself points to the specific genre he excelled in. Genre painting, by definition, focuses on scenes of ordinary life. Piltz's particular strength lay in his ability to elevate these ordinary moments, imbuing them with a quiet dignity and a sense of timelessness. He avoided the overtly political or socially critical themes that some Realist painters embraced, preferring instead to focus on the personal and the intimate. His works often tell a story, but it is usually a gentle, human-scale narrative rather than a grand historical or allegorical one.

His palette was typically warm and harmonious, contributing to the inviting and often cozy atmosphere of his interiors. His handling of light was skillful, used not only to model forms but also to create mood and highlight focal points within the composition. While not an Impressionist, he was certainly aware of the effects of light and atmosphere and incorporated them effectively into his realistic framework.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Several paintings stand out as representative of Otto Piltz's style and thematic concerns, showcasing his mastery of genre scenes and his empathetic portrayal of human subjects.

Idylle in der Stube (Indoor Idyll): This title itself encapsulates a central theme in Piltz's work. Such a painting would likely depict a peaceful domestic scene, perhaps a family gathered in a simple but comfortable room, engaged in quiet activities like reading, sewing, or children playing. Piltz excelled at capturing the intimate atmosphere of these interiors, using light and detail to create a sense of warmth and security. The "idyll" suggests an idealized vision of home and family life, a common aspiration in the 19th century.

Der Liebesbrief (The Love Letter), 1886: This work, an oil on wood panel measuring 39 x 50 cm, is a classic example of a sentimental genre scene. The theme of a love letter was popular among 19th-century painters, offering opportunities to explore emotions like anticipation, joy, or longing. Piltz would have focused on the figure receiving or reading the letter, capturing their expression and the surrounding environment to enhance the narrative. The choice of wood panel as a support was common for smaller, detailed works.

Holländischer Junge am Strand (Dutch Boy on the Beach) and Holländische Mädchen (Dutch Girls): These titles indicate Piltz's interest in subjects beyond his native Germany. The Netherlands, with its picturesque landscapes, distinctive traditional costumes, and rich artistic heritage (particularly the Dutch Golden Age genre painters like Johannes Vermeer or Pieter de Hooch), attracted many artists in the 19th century. Piltz's depictions of Dutch children suggest an engagement with these themes, likely focusing on their charming innocence and the specific cultural details of their attire and setting. These works demonstrate his ability to observe and render different cultural milieus with the same sensitivity he applied to German rural life.

Nahstunde (Sewing Lesson): This subject is another staple of genre painting, often depicting a young girl learning needlework from an older woman, perhaps her mother or grandmother. Such scenes celebrated domestic skills, intergenerational connection, and the quiet virtues of female industry. Piltz would have rendered the scene with his characteristic attention to detail in the figures' expressions, their clothing, and the textures of the fabrics they worked with.

Junger Frau im Dachau Tracht bei Besuch der alten Bauerin (Young Woman in Dachau Costume Visiting an Old Peasant Woman): This title is particularly descriptive and points to Piltz's interest in regional costumes and the interactions between different generations or social types. Dachau, near Munich, was an artists' colony, and its traditional Tracht (folk costume) was a popular subject. The scene of a visit suggests a narrative of respect, care, or perhaps the bridging of a generational gap, all themes that Piltz handled with empathy.

Peisen (Illustrations): Beyond his oil paintings, Piltz was also known for his illustrative work. His illustrations titled Peisen were published by Han's Publishing House in Frankfurt and also appeared in the popular family magazine Gärtnerbote. This demonstrates his versatility and his ability to reach a wider audience through print media. His skill in precise detail, particularly in rendering elements like peasant clothing, made his illustrations highly successful and sought after.

Contemporaries and Artistic Connections

Otto Piltz's career unfolded during a dynamic period in German art, and he was connected, either directly or through shared artistic currents, with numerous other artists.

In Weimar, alongside figures like Alexander Struys, Karl Gussow, and Wilhelm Zimmer, he contributed to the reputation of the Weimar School for genre painting. The school also attracted artists who would later become pioneers of modernism, such as Hans Olde (Hans Wilhelm Olde), who was instrumental in founding the Weimar Secession, indicating the evolving artistic landscape Piltz navigated.

During his time in Munich, he would have been aware of the leading figures of the Munich School, such as Franz von Defregger, whose Tyrolean genre scenes shared some thematic similarities with Piltz's work, and Wilhelm Leibl, whose uncompromising realism represented a different facet of the Munich art scene. The city was also home to artists like Carl Spitzweg, whose charming and humorous Biedermeier genre scenes had an enduring appeal.

In his later years in Pasing, near Munich, Piltz maintained a connection with the younger artist Franz Marc. Marc, who lived nearby, would become one of the leading figures of German Expressionism and a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter group. This connection, though perhaps more of a personal friendship than a direct artistic influence on either party's mature style, is an interesting footnote, linking Piltz to the next generation of avant-garde artists.

His friendship with Walter Schulte, a writer, journalist, and painter who reportedly lived with Piltz in Weimar and visited him in his later years, highlights the interdisciplinary connections common in artistic circles.

Other notable German genre painters of the broader 19th-century period whose work provides context for Piltz include Ludwig Knaus of the Düsseldorf School, whose depictions of peasant life were immensely popular, and Benjamin Vautier the Elder, also associated with Düsseldorf, known for his charming and detailed genre scenes. While Piltz developed his own distinct voice, his work can be seen as part of this wider European tradition of celebrating and documenting the lives of ordinary people.

The provided information also lists Josef Rummelspacher (1852-1921), active in the Saar-Alpine region, and Otto Mueller (1834-1903, a different Otto Mueller from the Brücke expressionist), known for peasant life and nature, as contemporaries. Otto Wilhelm Erdmann Eduard (1868-1920) is another artist from the same era. While direct collaborations or interactions with all these figures are not always detailed, their contemporaneous activity paints a picture of a vibrant and diverse German art world.

Later Years, Legacy, and Conclusion

Otto Piltz spent the last three decades of his life primarily in Munich and its environs, continuing to paint and exhibit. He passed away in Pasing, which by then had become a part of Munich, in 1910. His daughter, Marie Pilz, also pursued an artistic career, though as a ceramicist, indicating a continuation of artistic tradition within the family.

Otto Piltz's legacy lies in his sensitive and skilled contributions to German genre painting. In an era of significant social and artistic change, his work offered a vision of stability, tradition, and the enduring values of human connection and rural life. While he may not have been a radical innovator in the vein of the Impressionists or the later Expressionists, his art resonated deeply with the tastes and sentiments of his time. His paintings were highly regarded for their technical accomplishment, their narrative charm, and their empathetic portrayal of ordinary people.

His works are preserved in various private collections and can be found in some German museums, particularly those focusing on 19th-century art. They serve as valuable documents of a particular approach to art-making and a reflection of the cultural values of his era. Piltz's dedication to depicting the "idylls" of everyday life, whether in a Thuringian cottage, on a Dutch beach, or in a Bavarian farmhouse, provides a window into a world rendered with affection and meticulous care. He remains a noteworthy figure for those interested in German Romantic Realism and the rich tradition of genre painting that flourished in 19th-century Europe, an artist who skillfully captured the quiet poetry of the commonplace.