Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze, known universally by his adopted pseudonym Wols, stands as a pivotal yet enigmatic figure in twentieth-century European art. Born in Berlin, Germany, on May 27, 1913, his life was a tumultuous journey through the artistic and political upheavals of his time, culminating in a tragically early death in Paris, France, on September 1, 1951. A multi-talented individual, Wols was not only a groundbreaking painter but also an accomplished photographer, printmaker, and occasional musician and poet. His legacy is primarily associated with the post-war European movement of Tachisme, a form of lyrical, gestural abstraction, of which he was a crucial and highly influential pioneer. His work bridges the gap between the dreamlike visions of Surrealism and the raw, existential energy of Abstract Expressionism, creating a unique visual language that continues to resonate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Wols was born into a privileged environment. His father, Alfred Schulze, was a high-ranking civil servant in Berlin, serving as a legal advisor and chancellor for the state of Saxony, and was also known as a patron of the arts. This exposure to culture from a young age undoubtedly nurtured the nascent artistic sensibilities of the young Alfred Otto Wolfgang. The family moved to Dresden in 1919, a city with a rich artistic heritage. It was here, amidst a cultured household, that Wols began to develop his diverse talents. He learned the violin and showed an early interest in the natural sciences, hinting at the microscopic, detailed focus that would later characterize much of his visual art.

His serious engagement with the visual arts began around 1927, specifically with photography. This medium would remain important throughout his career, initially providing a more direct connection to the external world before his art turned increasingly inward. He briefly attended the renowned Bauhaus school in Berlin after being recommended by László Moholy-Nagy, a master of experimental photography and design. However, the structured environment of the Bauhaus did not suit Wols's temperament, and his time there was short-lived.

Parisian Immersion and Surrealist Connections

Seeking a more stimulating and less restrictive environment, Wols moved to Paris in 1932. This move proved decisive for his artistic development. Paris in the 1930s was the undisputed center of the avant-garde, buzzing with artistic innovation and intellectual ferment. Wols quickly integrated into this vibrant scene, making contact with prominent figures associated with the Surrealist movement. He met artists like Max Ernst and Joan Miró, and was acquainted with Fernand Léger, whose work, while distinct from Surrealism, was part of the broader modernist landscape.

During this period, Wols initially focused on photography, gaining some recognition. His photographic work from the 1930s often displays influences from both Surrealism, with its interest in the uncanny and the subconscious, and the sharp focus of New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), a movement prominent in Germany during the Weimar Republic. He captured portraits, cityscapes, and still lifes, often imbuing ordinary subjects with a strange intensity. He worked professionally, taking assignments for fashion magazines, which provided some income but stood in contrast to his more personal artistic explorations. His encounters with the Surrealists, particularly their emphasis on automatism and the exploration of the psyche, deeply influenced his approach, encouraging a move towards more intuitive and less representational forms of expression, primarily through drawing and watercolor.

The Shadow of War: Internment and Artistic Transformation

Wols's life took a dramatic and difficult turn with the outbreak of World War II. As a German national living in France, he was considered an "enemy alien" upon the declaration of war in September 1939. He was arrested and interned in various camps in southern France, including Les Milles near Aix-en-Provence, a former tile factory that housed many German and Austrian intellectuals and artists fleeing Nazism. Among his fellow internees were figures like Max Ernst and the writer Lion Feuchtwanger. This period of confinement, lasting intermittently until 1940, was marked by hardship, uncertainty, and deprivation, but it was also a period of intense artistic activity for Wols.

Confined and with limited materials, Wols produced a significant body of work, primarily small-scale drawings and watercolors on paper. These works mark a crucial shift in his art. Depicting fantastical creatures, cellular forms, and intricate, web-like structures, they move decisively away from external reality towards an exploration of inner worlds. Influenced by his earlier interest in science and the microscopic, and filtered through the lens of Surrealist automatism and the trauma of his situation, these works evoke a sense of anxiety, fragility, and metamorphosis. He explored concepts of "fragmentation" and "non-space," reflecting the chaos and existential dread of the war years. Artists like Georges Mathieu and the writer-painter Henri Michaux were also active during this period, exploring similar paths of abstraction and introspection, sometimes in shared circumstances of displacement or resistance. Wols's works from the internment camps are considered among his most original and poignant creations.

The Emergence of Tachisme: Post-War Abstraction

After his release from internment, Wols lived precariously in the south of France, often in poverty, with his French companion, Gréty Dabija, whom he later married. He continued to draw and paint watercolors. A pivotal moment came in 1945 when, encouraged by the Parisian art dealer René Drouin, Wols began to paint in oils. This marked the beginning of the final, and perhaps most influential, phase of his career. His first solo exhibition of paintings was held at Drouin's gallery in December 1945, followed by another in 1947. These exhibitions introduced his radical new style to the Parisian art world.

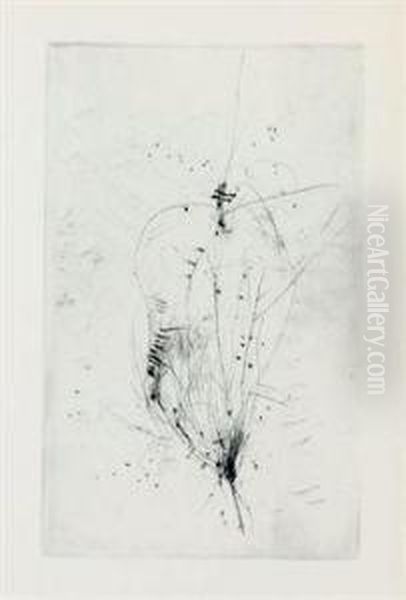

Wols's oil paintings from 1945 until his death in 1951 are prime examples of Tachisme (from the French word 'tache', meaning stain, blot, or spot). This style, often considered a European parallel to American Abstract Expressionism (associated with artists like Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning), emphasized spontaneity, gestural brushwork, and the materiality of paint itself. Wols applied paint thickly, often directly from the tube, scratching, scraping, and rubbing the surface, allowing drips and spatters to become integral parts of the composition. His canvases are typically small but possess an explosive intensity, suggesting turbulent inner landscapes, cosmic events, or microscopic biological processes.

This approach was part of a broader movement in post-war Paris known as Art Informel (Unformed Art) or Art Autre (Other Art), championed by the critic Michel Tapié. This movement rejected geometric abstraction and traditional notions of composition in favor of intuitive, expressive gestures that reflected the existential anxieties of the post-war era. Wols, alongside artists such as Jean Fautrier, Jean Dubuffet, Hans Hartung, Georges Mathieu, and Camille Bryen, was at the forefront of this development. His work, with its raw emotion and innovative techniques, profoundly impacted the direction of abstract painting in Europe.

Representative Works and Artistic Vision

While Wols's oeuvre is remarkably consistent in its intensity, certain works and series stand out. His early photographs remain significant, capturing a unique vision of Paris and its inhabitants in the 1930s. The hundreds of watercolors and drawings created during his internment and the subsequent years in the south of France represent a major body of work, showcasing his transition towards abstraction and his mastery of intricate, biomorphic forms. Works like the watercolor Aphorismes (Aphorisms, ca. 1940) exemplify this period, with delicate lines and washes creating complex, evocative imagery.

His post-1945 oil paintings are perhaps his most celebrated contributions. Titles are often simple, like Composition, or evocative, such as Le Fantôme Bleu (The Blue Phantom) or La Flamme (The Flame). The painting referred to as Unfinished (ca. 1945) captures the raw, process-oriented nature of his work, where the act of creation itself seems embedded in the final surface. These paintings often feature a central, turbulent mass of color and texture from which lines radiate outwards or inwards, suggesting both implosion and explosion, creation and decay. They convey a sense of looking through a microscope and a telescope simultaneously, revealing the hidden structures of both the inner self and the outer cosmos.

The Circus Wols project, conceived later in his life, reflects his multifaceted interests. It was envisioned as a kind of traveling exhibition or educational initiative combining his paintings, drawings, photographs, texts, and perhaps even music, aiming to bridge popular and high culture in a democratic spirit. Although not fully realized in his lifetime, the concept underscores his holistic view of art and its potential social role, even amidst his deeply personal and introspective style.

Collaborations, Connections, and Support

Throughout his career, Wols maintained connections with various figures in the art and literary worlds, although he was often described as solitary. His early association with Surrealists like Max Ernst was formative. His involvement with the Art Informel movement brought him into dialogue with contemporaries like Jean Dubuffet, known for his exploration of 'Art Brut' (Raw Art), the highly gestural painter Georges Mathieu, the textural innovator Jean Fautrier, and the poet-painter Camille Bryen. He also shared the experience of internment with artists who pursued their own paths, such as Henri Michaux.

Wols also engaged in illustration projects, creating etchings for texts by prominent writers. These included Jean-Paul Sartre, whose existentialist philosophy resonated with the themes in Wols's art, Franz Kafka, whose explorations of alienation and bureaucracy mirrored Wols's own experiences, Jean Paulhan (possibly the "Paul Jeanhault" mentioned in sources), René Solier, and Camille Bryen. Notable illustrated books include Visages et Nourritures (Faces and Foods) and L’invite des morts (The Guest of the Dead). These collaborations highlight the synergy between visual art and literature in post-war Paris.

Crucial support came from his gallerist, René Drouin, who provided him with materials and exhibition opportunities at a critical juncture. The provided information also mentions support from a "Jean-Luc Salomon," though Drouin is more widely recognized as his key promoter in the post-war years. This support was vital, given Wols's often precarious financial situation.

Personal Struggles and Tragic Demise

Wols's life was marked by profound personal struggles that ran parallel to his artistic breakthroughs. He suffered from chronic health problems, exacerbated by poverty and instability. He also battled severe alcoholism, which increasingly took a toll on his physical and mental well-being. His lifestyle was described by some as "merry and short," hinting at a bohemian existence lived with intensity but also recklessness, a pattern not uncommon among artists grappling with trauma and existential questions in the mid-20th century.

His political views also caused him trouble. In 1935, while traveling in Spain, he was arrested in Barcelona, reportedly for his controversial political stances or lack of proper papers. This incident reinforced his decision not to return to Nazi Germany, solidifying his life as an exile. Despite gaining limited residency in France in 1936, his status remained precarious, requiring him to report regularly to the police, a constant reminder of his statelessness and vulnerability.

His final years were spent in Paris, where despite growing recognition, his health deteriorated rapidly due to his alcoholism. Wols died tragically on September 1, 1951, at the age of only 38. The immediate cause was food poisoning, reportedly from consuming spoiled horse meat, but his weakened state due to chronic illness and alcohol abuse made him unable to recover. He died alone in a hotel room, a poignant end that seemed to reflect the solitude and fragility often conveyed in his art.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite his short life and relatively small output of oil paintings, Wols's impact on post-war art was immense. He is widely regarded as a key originator of Tachisme and Art Informel, influencing a generation of abstract painters in Europe and beyond. His emphasis on intuitive gesture, the exploration of the subconscious, and the expressive potential of paint material opened new avenues for artistic expression. His work provided a powerful European counterpoint to American Abstract Expressionism, demonstrating a shared interest in existential themes and radical abstraction, albeit often on a more intimate scale.

His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent artists who explored gestural abstraction and material experimentation, including Spanish artists like Antoni Tàpies and Manolo Millares, and German Informel painters such as K.O. Götz and Emil Schumacher. His unique blend of microscopic detail and cosmic scope, his ability to convey profound psychological states through abstract means, continues to fascinate artists, critics, and collectors.

Today, Wols's works are held in major international museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Tate Modern in London, and the Centre Pompidou in Paris, cementing his status as a major figure in 20th-century art history. His art serves as a powerful testament to the resilience of the creative spirit in the face of personal hardship and historical catastrophe, offering intricate, intense visions born from the crucible of modern European experience.

Conclusion: The Intense Vision of Wols

Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze, or Wols, remains a compelling figure whose art condensed the anxieties, traumas, and creative ferment of his time into a unique visual language. From his early, insightful photographs to his later, explosive abstract paintings, his work consistently explored the liminal spaces between the internal and external, the microscopic and the cosmic, order and chaos. As a pioneer of Tachisme and Art Informel, he helped redefine the possibilities of painting after World War II, leaving behind a body of work characterized by its raw honesty, technical innovation, and profound existential depth. His short, turbulent life mirrored the intensity found in his art, securing his place as a crucial, albeit tragic, innovator of modern abstraction.