The 19th century was a period of profound transformation in the art world, witnessing the ebb of Neoclassicism, the surge of Romanticism, and the nascent stirrings of Realism and eventually, Impressionism. Within this dynamic landscape, the art of printmaking, particularly engraving and etching, continued to play a crucial role in the dissemination of images, knowledge, and artistic visions. Among the skilled practitioners of this demanding craft was the Italian artist Paolo Fumagalli (1797-1873), an engraver and printmaker whose work, though perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his painter contemporaries, contributed significantly to the visual culture of his time. His meticulous skill brought to life a diverse range of subjects, from detailed costume studies and archaeological illustrations to evocative cityscapes and natural phenomena.

Understanding Fumagalli requires us to delve into the specific context of Italian art and printmaking during his lifetime. Italy, with its rich artistic heritage, was a fertile ground for artists. While grand painting and sculpture often took center stage, a vibrant tradition of printmaking thrived, serving various purposes: reproducing famous artworks for a wider audience, illustrating books and scientific treatises, and creating original artistic statements. Fumagalli operated within this tradition, demonstrating a versatility that allowed him to engage with different genres and projects, leaving behind a body of work that merits closer examination.

The Artistic Milieu of Early 19th-Century Italy

Paolo Fumagalli's career unfolded against a backdrop of significant artistic and cultural shifts in Italy. The early part of the century was still heavily influenced by Neoclassicism, championed by figures like the sculptor Antonio Canova and painters such as Andrea Appiani. This movement emphasized clarity, order, and idealized forms, drawing inspiration from classical antiquity. However, Romanticism was also gaining traction, bringing with it a focus on emotion, individualism, the sublime power of nature, and a fascination with history and exotic cultures. Painters like Francesco Hayez became leading exponents of Italian Romanticism.

Printmaking in this era was indispensable. Academies like the Brera Academy in Milan, a major artistic center, often had engraving departments, recognizing the importance of the medium. Engravers like Giuseppe Longhi, who was a professor at Brera, and the earlier, highly influential Raphael Morghen, set high standards for reproductive engraving, translating the nuances of paintings into linear masterpieces. The demand for illustrated books was also growing, covering subjects from travel and exploration to history, science, and fashion. It was in this environment, rich with artistic precedent and burgeoning demand for printed images, that Fumagalli honed his craft.

Paolo Fumagalli: A Profile in Engraving

Born in Italy in 1797, Paolo Fumagalli dedicated his artistic life to the intricate arts of engraving and printmaking. While specific details about his early training are not extensively documented, it is highly probable that he underwent a rigorous apprenticeship, a common path for aspiring engravers of his time. This would have involved mastering the demanding techniques of using the burin to incise lines onto a metal plate, as well as potentially other methods like etching, which offered a different quality of line and tonal possibility. His career spanned several decades, during which he produced a notable body of work characterized by precision and a keen observational eye.

Fumagalli's skills were sought after for significant illustrative projects, a testament to his ability to render complex subjects with clarity and accuracy. He was not merely a technician but an artist capable of interpreting and conveying the essence of his subjects, whether they were the intricate details of historical attire, the grandeur of ancient ruins, or the atmospheric effects of a natural landscape. His contributions, particularly to large-scale publications, helped to shape the visual understanding of various subjects for a 19th-century audience.

Landmark Contributions: "Le Costume Ancien et Moderne"

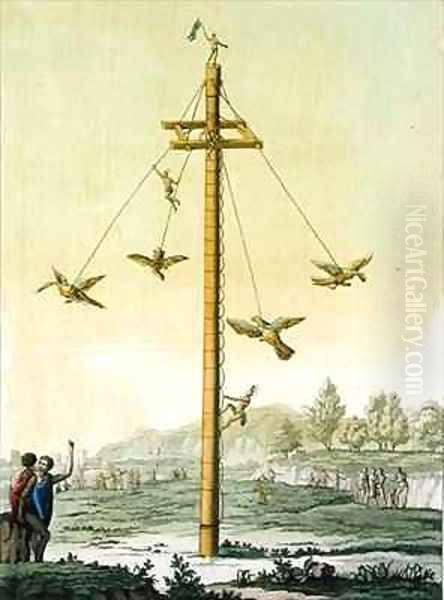

One of Paolo Fumagalli's most significant contributions was his work as an engraver for Giulio Ferrario's monumental publication, Le Costume Ancien et Moderne (The Ancient and Modern Costume). This ambitious, multi-volume work, published over several years in the early to mid-19th century, aimed to provide a comprehensive visual encyclopedia of costumes, customs, and monuments from around the world. Such encyclopedic projects were characteristic of the era's intellectual curiosity and the burgeoning interest in ethnography, history, and geography, fueled in part by colonial expansion and increased global travel.

Fumagalli's role in this project was crucial. He was responsible for engraving numerous plates, translating original drawings and paintings by various artists into the printable medium. These engravings depicted a vast array of subjects, from the attire of different cultures and historical periods to architectural landmarks and scenes of daily life. The precision required for such detailed work was immense, demanding a steady hand and a deep understanding of how to convey texture, form, and light through incised lines. His plates for Ferrario's Costume are a testament to his skill and patience, contributing to a work that became an important visual resource for scholars, artists, and the educated public. Other artists and engravers, such as G. Bramati and Angelo Biasioli, also contributed to this massive undertaking, highlighting the collaborative nature of such publications.

Illustrating Antiquity: The "Pompeia" Project

Another notable endeavor associated with Paolo Fumagalli is his involvement with the illustration of archaeological findings, specifically in a work titled Pompeia. This project, reportedly designed between 1829 and 1834, comprised a series of tables or plates showcasing the discoveries from the ongoing excavations at Pompeii. The unearthing of Pompeii and Herculaneum in the 18th century had ignited a fervent interest in Roman antiquity across Europe, profoundly influencing art, architecture, and design through the Neoclassical movement.

Fumagalli's illustrations for Pompeia would have served to document and disseminate knowledge about the architecture, frescoes, mosaics, and artifacts being brought to light. Such archaeological illustrations required a high degree of accuracy to be of scientific and historical value. While the dramatic and often romanticized views of Roman ruins by artists like Giovanni Battista Piranesi in the previous century had captivated the public imagination, the 19th century saw an increasing demand for more precise, documentary representations. Fumagalli's work in this area placed him within a tradition of artists contributing to the scholarly understanding of the classical past. His detailed engravings would have allowed those unable to visit the sites themselves to study the remnants of Roman civilization. The meticulous rendering of architectural details and decorative elements in these plates underscores his technical mastery.

Capturing Vistas and Phenomena: Landscapes and Cityscapes

Beyond historical and archaeological subjects, Paolo Fumagalli also applied his engraving skills to landscapes and cityscapes. A prominent example is his engraving titled Boston View from Castle William, looking up the Charles River towards Cambridge. This panoramic view, based on an earlier design by Thomas Pownall from around 1760, was engraved by Fumagalli and published as part of Ferrario's Le Costume Ancien et Moderne series, likely between 1815 and 1827. Such views of distant cities catered to the public's curiosity about the New World and other far-off lands. The engraving showcases key landmarks and the topography of Boston and its surroundings, demonstrating Fumagalli's ability to handle complex perspectives and a multitude of details within a single composition.

This type of work aligns with the strong tradition of veduta or view painting and printmaking, which had been exceptionally popular in Italy, with masters like Canaletto, Bernardo Bellotto, and Francesco Guardi setting a high standard in the 18th century. While Fumagalli's Boston view was reproductive, it required immense skill to translate Pownall's vision into a compelling engraved image.

Another fascinating example of his work in depicting natural scenes is a color etching illustrating a fog phenomenon in Baffin Bay. This piece reportedly shows the sun's rays scattering to form a semi-circular, dense fog. Such a subject indicates an interest in scientific observation and the sublime, often awe-inspiring aspects of nature, themes popular within Romanticism. The use of color etching, a more complex process, suggests Fumagalli's versatility in different printmaking techniques to achieve specific atmospheric effects. This interest in capturing the ephemeral qualities of nature connects him to broader artistic trends where landscape was increasingly seen as a subject worthy of serious artistic exploration, as seen in the works of painters like J.M.W. Turner in England, whose works were also widely disseminated through engravings.

Artistic Style, Technique, and Influences

Paolo Fumagalli's artistic style is primarily characterized by the meticulous precision inherent in the engraver's art. His lines are typically clean and controlled, defining forms with clarity and providing a wealth of detail. Whether depicting the intricate patterns of a fabric, the weathered stones of an ancient building, or the delicate foliage of a tree, his work exhibits a dedication to careful observation and faithful rendering. His focus on plant themes, trees, and rural architecture in some of his engravings suggests an appreciation for the natural world and the picturesque.

The provided information notes an influence of "European Modernism" in his later life, where he focused on detailed painting studies that he then incorporated into his engravings and prints. This is an interesting point, as "Modernism" as an art historical term typically refers to movements that emerged later in the 19th century and flourished in the 20th. It's possible this refers to a broader engagement with contemporary artistic trends towards greater realism or a more individualized approach to subject matter, moving beyond purely reproductive work. Perhaps it indicates an adoption of the more detailed, analytical approach seen in some strands of Realism, or simply a continuous refinement of his observational skills throughout his career. His lifespan (1797-1873) meant he witnessed the rise of Realism championed by artists like Gustave Courbet in France, and the early stirrings of Impressionism. While engraving is a more conservative medium, it's plausible that these broader shifts in visual culture had some impact on his approach.

The mention of a "nostalgic" quality in his art, reflecting a "reminiscence of a golden past," could be interpreted in several ways. It might relate to his engagement with historical and archaeological subjects, inherently looking back in time. Or it could be a more general Romantic sensibility, a longing for an idealized past or a more harmonious relationship with nature, themes often explored by Romantic artists and writers.

Fumagalli in Context: Contemporaries and Connections

To fully appreciate Paolo Fumagalli's place, it's helpful to consider him alongside other artists and printmakers of his era. In Italy, the tradition of architectural and view engraving continued with figures like Luigi Rossini, who, like Piranesi before him, produced impressive series of Roman views. Bartolomeo Pinelli was another contemporary known for his lively etchings of Roman life and costumes, capturing a more folkloric and everyday aspect of Italian culture.

The collaborative nature of large publishing projects like Ferrario's Costume meant that Fumagalli would have been aware of, and perhaps worked alongside, other engravers. The provided information mentions his name appearing with Carlo Petrini and Paolo Semenzato in exhibition contexts, suggesting professional interactions within the Italian art scene. While the exact nature of these relationships requires further research, it points to his participation in the artistic community.

Internationally, the world of printmaking was vibrant. In France, artists like Honoré Daumier were using lithography for powerful social commentary, while in Britain, engravers were crucial for reproducing the popular paintings of the day and for illustrating books and periodicals. The technical standards were high across Europe, and Fumagalli's work stands as a testament to the skill prevalent among Italian engravers.

The Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Paolo Fumagalli continued his artistic practice throughout a significant portion of the 19th century, passing away in 1873 at the age of 75 or 76. His career spanned a period that saw the beginnings of photography, a medium that would eventually revolutionize the reproduction and dissemination of images, impacting the traditional roles of engravers. However, during his lifetime, engraving remained a vital and respected art form.

His legacy lies in the body of work he produced, particularly his contributions to major illustrated publications. These works not only showcase his technical prowess but also served as important vehicles for education and the spread of visual information in an era before mass photography. His engravings of costumes, archaeological sites, and city views helped to shape public perception and understanding of these subjects. Today, his prints can be found in various collections, valued for their historical significance and artistic merit. While perhaps not a revolutionary innovator in the mold of a Goya (whose printmaking was highly expressive and personal), Fumagalli represents the skilled and dedicated artisan-engraver whose work was essential to the cultural fabric of the 19th century.

The study of artists like Paolo Fumagalli enriches our understanding of art history beyond the headline names. It reveals the intricate network of creators, publishers, and audiences that constituted the art world of the past. His meticulous engravings, whether depicting the grandeur of ancient Pompeii, the bustling cityscape of Boston, or the delicate patterns of a historical garment, offer a window into the visual culture and intellectual currents of his time, securing his place as a noteworthy Italian engraver of the 19th century. His dedication to his craft ensured that images of diverse worlds and historical epochs were preserved and shared, a contribution that remains valuable to this day.