Paul Camille Guigou stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in nineteenth-century French landscape painting. Deeply rooted in the sun-drenched terrain of his native Provence, Guigou dedicated his relatively short artistic career to capturing the unique light, rugged forms, and expansive vistas of this southern French region. Though associated with the later stages of the Barbizon School and sharing affinities with Realism, his work possesses a distinct clarity and intensity that foreshadows aspects of Impressionism, securing his place as a unique voice in the transition towards modern art.

His life, marked by an initial path towards a more conventional profession before fully embracing art, and his posthumous rediscovery, add layers to the appreciation of his luminous canvases. He remains celebrated for his authentic and deeply felt portrayals of the Provençal landscape, rendered with both sensitivity and structural rigor.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Paul Camille Guigou was born on February 15, 1834, in the small town of Villars, located in the Vaucluse department of Provence, France. His family was relatively affluent; his father worked as both a farmer and a notary, suggesting a comfortable bourgeois background. This upbringing in the heart of Provence undoubtedly instilled in him a profound connection to the region's distinctive environment from a young age.

Initially, Guigou did not pursue an artistic career. Following a more practical path, he began working as a notary's clerk in the nearby town of Apt. In 1851, he advanced to become a bailiff's clerk. His professional duties later took him to the bustling port city of Marseille in 1854, where he continued to work in the legal field. However, the allure of art proved irresistible.

While in Marseille, Guigou began to seriously cultivate his interest in painting. He initially received instruction from an obscure local teacher named Camp, but his most formative training came under the guidance of Émile Loubon at the École des Beaux-Arts de Marseille. This period marked a crucial turning point, setting him firmly on the path to becoming a professional artist.

The Influence of Marseille and Émile Loubon

Marseille, during the mid-nineteenth century, was a vibrant center for the arts in southern France, distinct from the dominant Parisian scene. Émile Loubon (1809-1863) was a pivotal figure in this milieu. As the director of the municipal art school, Loubon was not only an accomplished painter himself but also an influential teacher who championed a regional artistic identity focused on the Provençal landscape.

Loubon had connections to the Barbizon School painters, having spent time near the Forest of Fontainebleau. He encouraged his students, including Guigou, to abandon studio conventions and work directly from nature – the practice known as en plein air. This approach, emphasizing direct observation and capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, was fundamental to the Barbizon ethos and would become central to Guigou's own artistic practice.

Under Loubon's mentorship, Guigou honed his skills and deepened his commitment to landscape painting. Loubon's emphasis on depicting the specific character of the Provençal environment – its harsh sunlight, arid terrain, and dramatic topography – resonated strongly with Guigou's own sensibilities. The Marseille school provided a supportive environment for Guigou to develop his unique vision, grounded in the realities of his native region. Other artists associated with the Marseille scene, like Adolphe Monticelli, also contributed to the city's artistic vibrancy, though Monticelli's style was markedly different from Guigou's.

Embracing the Landscape: The Call of Provence

Guigou's true passion lay in the landscapes of Provence. Despite his initial legal work, his artistic calling centered entirely on depicting the region he knew so intimately. Encouraged by Loubon and inspired by the burgeoning Realist movement, Guigou dedicated himself to exploring and painting the diverse terrains around Marseille, Aix-en-Provence, and his native Vaucluse.

He was known to wander the hills and valleys, often alone, seeking out specific motifs and atmospheric conditions. He favored the rugged garrigue landscapes, the banks of the Durance river, the foothills of Mont Sainte-Victoire (later made famous by Paul Cézanne), and the vast, stony plains like La Crau. His commitment to en plein air painting was unwavering; he sought to capture the intense luminosity and sharp contrasts created by the southern sun directly onto his canvas.

This dedication meant immersing himself in the environment. His paintings often convey a sense of solitude and tranquility, reflecting his personal experience of walking and working in these sometimes remote locations. He wasn't merely documenting topography; he was translating the feeling, the heat, and the unique visual character of Provence into paint. This profound connection to place became the defining feature of his oeuvre.

Artistic Development and Influences: Barbizon and Realism

Guigou's artistic development was shaped by several key influences prevalent in mid-nineteenth-century French art. His initial training with Loubon firmly connected him to the principles of the Barbizon School. Like Barbizon masters such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Théodore Rousseau, and Charles-François Daubigny, Guigou valued direct observation of nature, truthfulness in representation, and an appreciation for the specific character of the French landscape.

The Barbizon emphasis on capturing atmosphere and light, often through subtle tonal harmonies, is evident in Guigou's work, particularly in his handling of skies and distant vistas. He shared their commitment to depicting rural life and landscapes without overt romanticization, focusing instead on the inherent beauty and structure of the natural world. The influence of Barbizon animal painters like Constant Troyon can also be subtly felt in the integration of figures or animals within some of his landscapes.

Furthermore, Guigou was significantly impacted by the Realist movement, spearheaded by Gustave Courbet. After visiting Paris, likely around 1859, Guigou encountered Courbet's powerful, unidealized depictions of contemporary life and landscape. Courbet's bold application of paint and his focus on the tangible reality of his subjects encouraged Guigou to adopt a more vigorous technique and a heightened sense of materiality in his own work. This Realist influence is visible in the solidity of his forms and the directness of his compositions. Guigou synthesized these influences, blending Barbizon sensitivity with Realist strength, to forge his own distinctive style. Other Realists like Jean-François Millet, known for his depictions of peasant life, also contributed to the artistic climate that valued truthful representation, which resonated with Guigou's focus on the authentic Provencal environment.

The Provençal Vision: Light, Color, and Form

What truly distinguishes Guigou's work is his specific vision of Provence. He possessed an extraordinary ability to render the region's unique light – a clear, intense sunlight that defines forms sharply and creates strong contrasts between illuminated areas and deep shadows. His palette often features warm ochres, earthy reds, vibrant greens, and brilliant blues, reflecting the colors of the soil, vegetation, and sky under the Mediterranean sun.

Unlike the softer, more diffused light often found in the landscapes of northern France painted by Corot or Daubigny, Guigou's light is crisp and clarifying. It models the rugged terrain, defines the textures of rock and foliage, and creates a sense of palpable heat and dryness. He was particularly adept at capturing the vast, open skies of Provence, often dedicating a significant portion of his canvas to them, filled with light or dramatic cloud formations.

His compositions frequently emphasize the horizontal expanse of the landscape, employing panoramic formats or high horizons that draw the viewer into the scene. He often structured his paintings with strong diagonal lines, such as roads or riverbanks receding into the distance, creating a dynamic sense of space. Works like Paysage de la Crau (Landscape of La Crau) exemplify this approach, showcasing the wide, stony plain under a luminous sky. Les Collines d'Allauch (The Hills of Allauch) and Lavandières au bord de la Durance (Washerwomen on the Banks of the Durance) are other key examples demonstrating his mastery of Provençal light and landscape structure.

Technique and Style: Clarity and Structure

Guigou developed a technique characterized by clarity, precision, and a strong sense of underlying structure. While influenced by Courbet's bolder application of paint, Guigou's brushwork is often more controlled and refined, particularly in his mature works. He applied paint smoothly in many areas, especially skies and distant planes, creating a sense of calm and luminosity.

However, he could also employ more textured brushstrokes to render the roughness of rocks, the foliage of olive trees, or the sun-baked earth, adding tactile quality to his scenes. His drawing is firm and assured, defining the contours of hills, trees, and buildings with accuracy. This emphasis on clear delineation of forms distinguishes his work from the more atmospheric dissolution of form seen in later Impressionism.

His compositions are carefully constructed, often balancing horizontal elements with vertical accents like cypress trees or distant village structures. The use of panoramic formats, relatively uncommon at the time for easel paintings, allowed him to convey the vastness and openness of the Provençal landscape effectively. This compositional clarity, combined with his precise rendering of light and color, gives his paintings a sense of timelessness and objective observation, even while conveying a deep personal connection to the subject. His approach can be contrasted with the more turbulent style of his Marseille contemporary Monticelli, or the softer focus of Corot.

Paris and the Salons: Seeking Recognition

Around 1862, seeking broader recognition beyond the regional scene of Marseille, Guigou moved to Paris. This move placed him at the center of the French art world, allowing him to engage more directly with prevailing artistic trends and institutions, most importantly the official Paris Salon. He began exhibiting regularly at the Salon from 1863 onwards.

Despite his consistent participation in the Salon, Guigou failed to achieve significant critical acclaim or commercial success during his lifetime. The Parisian art establishment, while gradually opening up to landscape painting thanks to the efforts of the Barbizon generation, still often favored historical or more traditionally composed subjects. Furthermore, Guigou's specific focus on the landscapes of Provence might have been perceived as too regional or specialized by some critics accustomed to the scenery of northern France.

His style, while rooted in accepted traditions like Barbizon and Realism, perhaps lacked the dramatic flair or narrative content that often attracted attention at the Salon. He remained somewhat isolated from the burgeoning avant-garde circles that would soon coalesce into the Impressionist movement, although his work shared certain affinities with theirs, particularly the emphasis on light and en plein air practice. Painters like Eugène Boudin and Johan Barthold Jongkind, who were also exploring light effects on the Normandy coast, were perhaps gaining more traction as precursors to Impressionism in the Parisian context.

Connections and Contemporaries

While Guigou maintained a strong individual artistic identity, he existed within a network of artistic connections and influences. His primary mentor, Émile Loubon, linked him directly to the Barbizon tradition. His engagement with Gustave Courbet's Realism was crucial for the development of his technique and approach to subject matter.

In Provence, he was part of a generation of artists dedicated to depicting their region, although his style remained distinct. While Paul Cézanne, also from Provence, would later revolutionize painting with his structural analysis of the landscape (including Mont Sainte-Victoire, a subject Guigou also painted), Guigou's approach remained more tied to faithful observation within the Realist-Barbizon framework.

In Paris, Guigou would have been aware of the work of other landscape painters exhibiting at the Salon. His contemporaries included the established Barbizon figures like Corot, Rousseau, Daubigny, and Millet, as well as younger artists who were pushing the boundaries of landscape representation. These included Boudin and Jongkind, whose atmospheric coastal scenes emphasized fleeting light effects, paving the way for Impressionism.

Although Guigou died in 1871, just before the first Impressionist exhibition in 1874, his dedication to en plein air painting, his focus on capturing specific light conditions, and his bright palette connect him to the spirit of early Impressionists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Alfred Sisley. He can be seen as a transitional figure, rooted in mid-century traditions but anticipating future developments.

Representative Works: Capturing Provence

Guigou's legacy rests on a body of work consistently focused on the Provençal landscape. Several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his style and concerns:

Paysage de Provence (La Route de la Gineste) (c. 1860): This work, depicting a road winding through the rugged hills near Marseille, exemplifies his ability to capture the intense light and arid atmosphere of the region. The composition leads the eye into the expansive landscape under a vast, luminous sky.

Les Collines d'Allauch (c. 1862): Shows his mastery in rendering the undulating forms of the Provençal hills, bathed in sunlight. The clarity of the air and the precision of the details are characteristic.

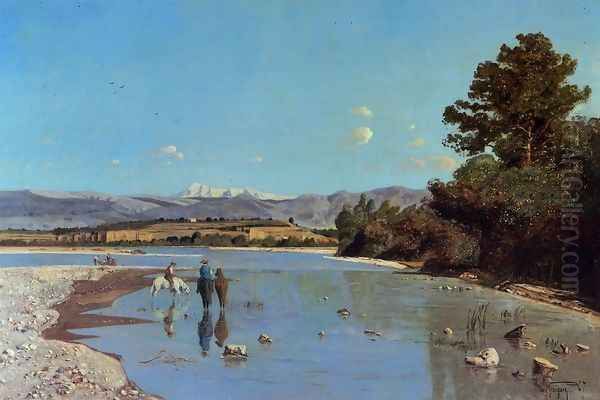

Lavandières au bord de la Durance (Washerwomen on the Banks of the Durance) (c. 1862): This painting combines landscape with genre elements. The figures of the washerwomen are integrated naturally into the scene, dominated by the wide riverbed and the clear light reflecting off the water and stones. It showcases his skill in depicting water and reflections.

Paysage de la Crau (Landscape of La Crau) (c. 1865-70): A powerful depiction of the vast, stony plain between Arles and the Alpilles. The high horizon emphasizes the flatness and expanse of the terrain, while the sky dominates the composition, filled with the characteristic Provençal light.

Le Mont Saint-Loup (date uncertain): Likely depicting a specific peak or hill formation, this work would showcase his interest in the geological structures of the landscape.

Tamaris au bord de la mer près de Marseille (Tamarisks by the Sea near Marseille) (c. 1867): Demonstrates his ability to capture coastal scenes, focusing on the interplay of light, water, and vegetation specific to the Mediterranean shore.

These works, among many others, consistently reveal Guigou's dedication to his chosen subject matter and his unique ability to translate the visual experience of Provence onto canvas with clarity, structure, and sensitivity.

Final Years and Premature Death

Paul Guigou spent his final years primarily in Paris, continuing to paint and exhibit at the Salon. He also maintained his deep connection to Provence, likely returning periodically to sketch and gather inspiration. Despite his lack of widespread fame, he remained dedicated to his artistic vision.

Tragically, his career was cut short. Paul Camille Guigou died suddenly in Paris on December 21, 1871, from a stroke (apoplexy). He was only 37 years old. His premature death meant that he did not live to see the emergence of Impressionism as a major force in the art world, nor did he have the opportunity to fully develop his artistic potential or achieve the recognition that might have come with a longer career.

His passing occurred during a tumultuous period in French history, following the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune. This context, combined with his limited fame during his lifetime, contributed to his work falling into relative obscurity for several decades after his death.

Posthumous Rediscovery and Legacy

For nearly thirty years after his death, Paul Guigou and his work were largely forgotten by the broader art world. However, the turn of the twentieth century brought a renewed interest in nineteenth-century landscape painting and regional artistic traditions. Guigou's work began to be rediscovered and re-evaluated.

A key moment came with the Exposition Universelle of 1900 in Paris, which included a centennial exhibition of French art that likely featured works by artists of Guigou's generation. Subsequently, exhibitions dedicated specifically to his work were organized, notably by prominent Parisian galleries like Bernheim-Jeune in the early 1900s. These shows reintroduced his luminous Provençal landscapes to critics and collectors.

Critics began to appreciate the unique qualities of his work: the clarity of his light, the structural integrity of his compositions, and his authentic portrayal of Provence. He came to be seen not just as a follower of Barbizon or Realism, but as an artist with a distinct personal vision, and perhaps as an important precursor to later movements, bridging the gap between mid-century realism and the light-filled canvases of the Impressionists.

Today, Paul Camille Guigou is recognized as one of the foremost painters of the Provençal landscape in the nineteenth century. His works are held in major museum collections in France, including the Musée d'Orsay in Paris and museums in Marseille and other Provençal cities, as well as internationally, such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. His legacy lies in his unwavering dedication to his native region and his ability to capture its essential character with enduring clarity and beauty.

Conclusion: The Enduring Light of Provence

Paul Camille Guigou's artistic journey was one of deep connection to place. From his early life in the Vaucluse to his mature years spent exploring the landscapes around Marseille and the Durance valley, Provence was his constant subject and inspiration. Guided by the principles of en plein air painting learned from Émile Loubon and fortified by the Realism of Courbet, he developed a distinctive style characterized by luminous clarity, strong composition, and a vibrant palette reflecting the southern French light.

Though his life was short and recognition came late, Guigou created a significant body of work that captures the essence of the Provençal landscape with remarkable fidelity and sensitivity. He stands as a testament to the richness of regional artistic traditions within France and as an important figure in the evolution of landscape painting in the nineteenth century. His paintings continue to resonate today, offering viewers a timeless vision of the sunlit hills, plains, and riverbanks of Provence, rendered by a hand that knew them intimately.