Per Ekström (1844–1935) stands as a significant figure in Swedish art history, a landscape painter whose canvases captured the unique light and atmosphere of his homeland, particularly the stark beauty of the island of Öland and the evocative power of the setting sun. Working during a period of transition in European art, Ekström absorbed influences from France but forged a distinct path, creating works that resonate with both romantic sensibility and a keen observation of nature. His long career spanned from the academic traditions of the mid-19th century to the evolving artistic landscape of the early 20th century.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Ekeshagen, Segerstad parish, on the island of Öland, Sweden, Per Ekström's artistic journey began under the tutelage of his father, a house painter. This early exposure to pigments and brushes likely instilled a foundational understanding of the craft. Recognizing his son's talent, his father provided initial training, laying the groundwork for a future dedicated to art. This practical beginning was common for artists of the era, offering a hands-on approach before more formal instruction.

Seeking to refine his skills, Ekström enrolled at the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts (Konstakademien) in Stockholm. The Academy, at the time, was steeped in the classical and romantic traditions prevalent across Europe. However, Ekström reportedly felt constrained by the academic curriculum, finding himself increasingly drawn to the newer currents emerging from France, particularly the move towards greater naturalism and the direct study of landscape. His time at the Academy provided technical proficiency, but his artistic heart yearned for a different mode of expression.

The Call of France: Paris and the Barbizon Influence

The allure of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the latter half of the 19th century, proved irresistible. In 1876, with the crucial support of a stipend from King Oscar II of Sweden, Ekström made the pivotal move to France. This royal patronage underscores the recognition his talent had already garnered within his home country. Paris offered exposure to a vibrant artistic scene, a melting pot of ideas and styles that contrasted sharply with the more conservative environment of Stockholm.

It was in France that Ekström encountered the works that would profoundly shape his artistic direction. He was particularly captivated by the painters of the Barbizon School. This group of artists, including figures like Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Charles-François Daubigny, and Narcisse Diaz de la Peña, had rejected the idealized landscapes of Neoclassicism. Instead, they focused on depicting the French countryside with a newfound realism, emphasizing direct observation, the effects of light and atmosphere, and often portraying rural life with dignity.

Ekström was also deeply influenced by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. While associated with Barbizon, Corot possessed a unique lyrical quality, blending realism with a soft, poetic sensibility. His mastery of tonal values and his ability to capture fleeting moments of light left a lasting impression on the young Swedish painter. The Barbizon emphasis on plein air (outdoor) sketching, though perhaps not fully adopted by Ekström in his finished works, certainly informed his approach to observing and understanding the nuances of the natural world.

Developing a Signature Style: Light, Mood, and the Swedish Landscape

Inspired by his French experiences, Ekström began to develop his characteristic style. He became particularly renowned for his depictions of sunsets, often set over the flat, open landscapes of his native Öland or other desolate terrains. These scenes were not merely topographical records; they were imbued with mood and atmosphere, capturing the dramatic transitions of light and color as day turned to night. His brushwork, influenced by the French examples, likely became looser and more expressive than traditional academic techniques allowed.

His paintings often feature a low horizon line, emphasizing the vastness of the sky and the dominance of light. The sun itself, whether setting in fiery glory or diffused through haze, frequently becomes the focal point, casting long shadows and illuminating the landscape in warm, evocative tones. This focus on the transient effects of light connects him spiritually to the concerns of the Impressionists, such as Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro, although Ekström's style remained distinct, often retaining a stronger sense of structure and a more somber or romantic mood compared to the high-keyed palette and broken brushwork of mainstream French Impressionism.

Ekström successfully synthesized the realism learned from the Barbizon painters with a lingering Romantic sensibility, creating landscapes that felt both true to nature and emotionally resonant. His work often conveys a sense of solitude and quiet grandeur, reflecting the character of the Swedish landscapes he favored. He wasn't merely painting what he saw, but how the scene felt, particularly the powerful, almost spiritual quality of light at the beginning and end of the day.

Recognition and Return to Sweden

Ekström's time in France brought significant recognition. He made his debut at the prestigious Paris Salon in 1878, a critical step for any artist seeking international validation. His work was well-received, culminating in a major honor: a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) in Paris in 1889. This award cemented his reputation on the international stage. He continued to exhibit, participating in the Paris Exposition of 1900 and reportedly receiving another gold medal in 1901, further testament to his sustained acclaim.

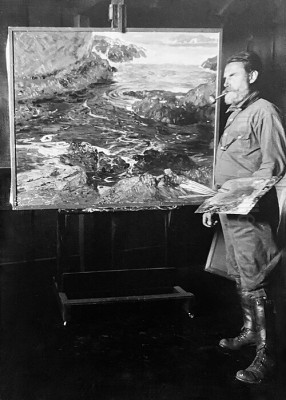

Despite his success abroad, Ekström eventually chose to return to Sweden. He settled primarily in Stockholm but maintained strong ties to Öland, returning frequently, especially during the summers. In Stockholm, he established a studio in the Birger Jarls Bazar, noted as one of the city's first modern office buildings – an interesting juxtaposition of the traditional landscape painter within a symbol of burgeoning modernity.

His reputation preceded him, and he found support among Swedish collectors and cultural figures. The influential Gothenburg-based collector and patron Pontus Fürstenberg, who also supported artists like Anders Zorn and Carl Larsson, was known to recommend Ekström's work. Ekström also moved within the cultural circles of the time, associating with prominent figures such as the multifaceted writer and artist August Strindberg, and fellow painters like Georg Pauli and Hanna Pauli, who were themselves key players in the Swedish art scene.

Later Career and "Atmospheric Impressionism"

In the 1890s, Ekström's style continued to evolve. Some critics and historians have applied the term "Stämningsimpressionism" (often translated as Mood or Atmospheric Impressionism) to his work from this period and later. This term distinguishes his approach from the optical concerns of French Impressionism, highlighting instead the focus on capturing a specific mood or atmosphere, often through subtle tonal harmonies and evocative light. During this time, he expanded his subject matter to include scenes from the Jämtland region and depictions of Stockholm's waterways, alongside his continued exploration of Öland's landscapes.

His later works, such as Sunset (dated 1928) and Sun on Ice (dated 1920), demonstrate his enduring fascination with the effects of light on the natural world. These paintings, executed in oil, typically bear his signature and the date at the bottom, consistent with his practice throughout his career. Even in his later years, the interplay of light, atmosphere, and the specific character of the Swedish landscape remained central to his artistic vision. Works like Forest Landscape at Dawn (1879) and Autumn Landscape with Setting Sun showcase his mastery in capturing these specific moments.

A key example of his mature style is Winter Landscape. Motif from Öland (1890), now housed in the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm. This painting likely embodies many of his characteristic traits: the expansive Öland landscape, the specific quality of winter light, and the evocative, perhaps slightly melancholic, atmosphere that defines much of his oeuvre. His dedication to the Öland landscape made him one of its foremost interpreters in Swedish art.

Legacy and Place in Art History

Per Ekström occupies a unique position in Swedish art. He acted as a bridge, absorbing the progressive influences of French landscape painting, particularly the Barbizon School and the tonal lyricism of Corot, and adapting them to a distinctly Swedish context. While aware of Impressionism, he charted his own course, prioritizing mood and atmosphere over the scientific exploration of light and color pursued by artists like Monet, Pissarro, or Alfred Sisley.

His focus on the specific light conditions of Scandinavia, especially the dramatic sunsets and the ethereal light of dawn and dusk, distinguishes his work. He stands alongside other prominent Swedish artists of his generation who sought to define a national artistic identity while engaging with international trends, such as the portraitist Anders Zorn, the idyllic domestic painter Carl Larsson, and the wildlife specialist Bruno Liljefors. While their subject matter differed, they shared a commitment to depicting Swedish life and landscape with authenticity and skill.

Ekström's influence might also be seen in the context of later Swedish landscape painters who continued to explore mood and light, perhaps including figures associated with the National Romanticism movement, like Prince Eugen or members of the Varberg School such as Karl Nordström, though direct mentorship links may be tenuous. His primary legacy lies in his powerful and consistent vision of the Swedish landscape, particularly Öland, rendered with a distinctive blend of realism and atmospheric poetry. His numerous awards and consistent exhibition record attest to the high regard in which he was held during his lifetime, both at home and abroad. Today, his paintings remain evocative portals into the soul of the Swedish landscape.

Conclusion: The Enduring Light

Per Ekström's long and productive career resulted in a body of work celebrated for its atmospheric depth and its sensitive portrayal of light. From his early training and academic studies to his transformative experiences in France and his eventual return to the landscapes that defined him, he remained dedicated to capturing the essence of nature, particularly the dramatic beauty of the rising and setting sun over the open terrains of Sweden. Influenced by Corot and the Barbizon masters like Rousseau and Millet, he forged a personal style that resonated with the sensibilities of his time while retaining a unique Nordic character. His paintings, found in major Swedish collections and appearing in auction records like the noted "Moor Landscape with Trees and Cows," continue to be appreciated for their technical skill and their profound connection to the natural world, securing Per Ekström's place as a master of Swedish landscape painting.