Introduction: An Artist of Quiet Distinction

Peter De Wint stands as one of the most accomplished and distinctive figures in the golden age of English watercolour painting. Flourishing in the first half of the nineteenth century, he captured the essence of the British landscape with a unique blend of naturalism, breadth, and quiet poetry. Born in England to a father of Dutch descent, De Wint brought a subtle echo of the Dutch landscape tradition to his depictions of the rolling fields, meandering rivers, and ancient architecture of his homeland. Though he also worked in oils, it is his mastery of watercolour, particularly his broad, atmospheric washes and harmonious compositions, that secured his lasting reputation. He was a key member of the Society of Painters in Water Colours, contributing significantly to the elevation of the medium during a period of intense artistic innovation and rivalry.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Peter De Wint was born on January 21, 1784, in Stone, Staffordshire. His father, Dr. Henry De Wint, was a physician whose family had emigrated from Holland. His mother hailed from a Dutch-American background. Initially, the young Peter was destined to follow his father into the medical profession. However, his artistic inclinations proved stronger, and his path diverged towards the visual arts, a decision that would enrich the landscape tradition in Britain.

In 1802, De Wint's formal artistic training began when he was apprenticed to the prominent engraver and painter, John Raphael Smith, in London. Smith, known for his mezzotints and portraits, provided a practical grounding. However, De Wint's passion lay firmly in landscape. During his apprenticeship, he formed a crucial friendship with a fellow pupil, William Hilton the Younger, who would later become a respected historical painter and Keeper of the Royal Academy. This friendship proved deeply influential, both personally and professionally.

De Wint showed early promise and ambition. In 1806, four years into his apprenticeship, he negotiated his release from the remaining term by agreeing to produce eighteen oil paintings for Smith over the following two years. This arrangement granted him the freedom to pursue his own artistic development more independently. Around this time, he also likely benefited from the circle surrounding Dr. Thomas Monro, a physician and passionate art collector whose home served as an informal 'academy' for young artists. Here, aspiring talents like J.M.W. Turner and Thomas Girtin had earlier honed their skills by copying works from Monro's collection, fostering an environment of learning and mutual influence. De Wint's association with this milieu would have exposed him to the forefront of watercolour practice.

Furthering his formal education, De Wint enrolled as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in 1809. Although the Academy primarily championed oil painting and historical subjects, studying there provided De Wint with valuable instruction in drawing and composition, and the opportunity to exhibit. He first showed his work at the Royal Academy exhibition in 1808, marking his public debut. While he continued to exhibit oils occasionally at the RA throughout his career, his primary allegiance and greatest contributions would lie with the medium of watercolour.

The Society of Painters in Water Colours: A Professional Home

The early nineteenth century witnessed a growing professionalisation among watercolour artists, who sought venues dedicated to their medium, distinct from the oil-dominated Royal Academy. Peter De Wint became involved early on with these efforts. In 1809, he was associated with the short-lived Associated Artists in Water Colours. More significantly, his talent was quickly recognised by the established Society of Painters in Water Colours (often referred to as the 'Old' Society or OWS, later the Royal Watercolour Society).

De Wint was elected an Associate Member of the OWS in 1810 and became a Full Member in 1811 (or 1812, sources slightly vary). This society, founded in 1804, was instrumental in raising the status and visibility of watercolour painting. Its annual exhibitions became major events in the London art calendar, showcasing the technical brilliance and expressive range achievable in the medium. De Wint became one of its most consistent and admired exhibitors for nearly four decades.

Within the OWS, De Wint worked alongside many leading watercolourists of the day. Figures such as John Varley, a highly influential teacher whose pupils included David Cox, Copley Fielding, and John Linnell, was a prominent member. David Cox himself, known for his vigorous, breezy landscapes, was a contemporary. Other notable members during De Wint's tenure included Joshua Cristall, known for his classical figures and rustic scenes, Anthony Vandyke Copley Fielding, who later became President and was famed for his atmospheric seascapes and downland views, and Samuel Prout, celebrated for his picturesque depictions of European architecture. De Wint's consistent, high-quality contributions helped solidify the Society's reputation and demonstrated the power of watercolour for capturing the nuances of the British landscape.

Artistic Style: Breadth, Harmony, and Naturalism

Peter De Wint's style is characterised by its breadth, simplicity, and profound connection to nature. He eschewed the dramatic turbulence found in some works by J.M.W. Turner or the detailed, almost scientific observation of John Constable. Instead, De Wint sought a harmonious representation of the landscape, emphasizing tranquility, space, and the quiet dignity of rural life and ancient structures.

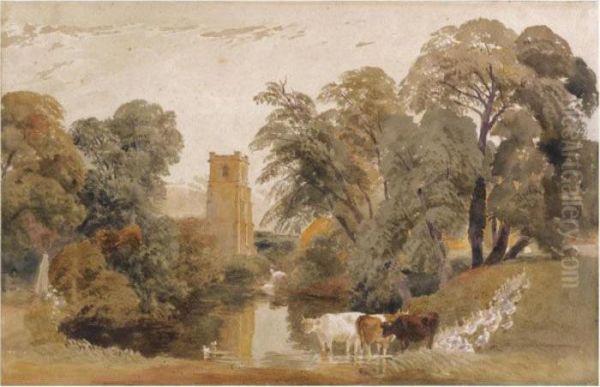

His technique was perfectly suited to his vision. He favoured broad, fluid washes of transparent watercolour, often applied with a full brush onto dampened paper. This allowed colours to blend softly and created luminous, atmospheric effects. He was a master of tone, building depth through subtle gradations and layers of colour rather than relying heavily on line. His palette tended towards warm, earthy tones – greens, browns, ochres, and soft blues – reflecting the natural colours of the English countryside.

A distinctive feature of many De Wint watercolours is their panoramic format, often using long, low horizontal compositions. This emphasizes the breadth of the landscape, drawing the viewer's eye across expansive fields, wide river valleys, or distant horizons under vast, subtly rendered skies. This compositional preference, along with his structured approach to landscape elements, shows a clear affinity with the great seventeenth-century Dutch landscape painters like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema, whose work he admired and whose influence is often noted by art historians. The influence of the classical landscape tradition, particularly the harmonious compositions of Claude Lorrain, can also be discerned in the balanced structure of his views.

De Wint worked directly from nature, making numerous outdoor sketches during his summer tours. These sketches often possess a remarkable freshness and immediacy. Back in the studio, he would work these up into more finished exhibition pieces. While his finished works are carefully composed, they retain a sense of spontaneity and fidelity to the observed scene. He captured the specific quality of English light and weather – the soft, diffused light, the dampness in the air, the lush greens of pastureland – with exceptional sensitivity. His handling of foliage is often broad and suggestive rather than minutely detailed, contributing to the overall unity and atmospheric quality of his work.

Subject Matter: The Heart of England

Peter De Wint's primary subject was the landscape of England, particularly the agricultural heartlands. While he undertook sketching tours to various regions, including North and South Wales, the Lake District, and parts of Yorkshire and the South Coast, he is most strongly associated with the county of Lincolnshire.

His deep connection to Lincolnshire stemmed from his marriage in 1810 to Harriet Hilton, the sister of his close friend, the painter William Hilton RA. The Hilton family resided in Lincoln, and through regular visits, De Wint developed an intimate knowledge and affection for the region's distinctive scenery. The flat, expansive fields, the slow-moving rivers like the Witham, the vast skies, and the towering presence of Lincoln Cathedral provided him with subjects perfectly suited to his broad, panoramic style. He painted numerous views of Lincoln itself, often featuring the cathedral rising majestically above the surrounding landscape, as seen from the Brayford Pool or across the fens.

Beyond Lincolnshire, the Thames Valley was another favourite sketching ground. He captured the gentle, pastoral beauty of the river and its surrounding meadows and villages. Harvest scenes were a recurring theme throughout his work, depicting labourers gathering corn under wide summer skies. These scenes convey a sense of timeless rural activity and the bounty of the land, rendered without overt sentimentality but with a deep appreciation for the rhythms of country life. Works like Harvest Time, Lancashire or Cornfield exemplify his ability to imbue these everyday agricultural subjects with quiet dignity and compositional strength.

De Wint generally focused on the cultivated landscape rather than wild, rugged nature. His views often include elements of human presence – farm workers, cattle watering, distant villages, country houses, or boats on a river – integrating them harmoniously within the broader natural setting. He captured the peaceful coexistence of humanity and nature in the English countryside.

Architectural Views and Other Works

While predominantly a landscape painter, Peter De Wint also possessed considerable skill in depicting architecture. His training likely included architectural drawing, and he brought the same sensitivity to light, tone, and atmosphere to his studies of buildings as he did to his landscapes. He frequently incorporated architectural elements into his wider views, such as distant cathedrals, churches, castles, or bridges, using them as focal points or anchors within the composition.

Lincoln Cathedral was a subject he returned to repeatedly, capturing its grandeur from various viewpoints and under different light conditions. He also painted views of other significant structures, including castles like Kenilworth Castle, often depicted in a state of picturesque ruin, and views in historic cities like Oxford. His work for the Oxford Almanack, an annual publication featuring engravings of Oxford scenes, further demonstrates his proficiency in this area. These architectural subjects were rendered with an understanding of their structure and mass, but always integrated into their landscape setting, emphasizing their relationship with the surrounding environment.

Although watercolour was his primary medium, De Wint continued to paint in oils throughout his career, occasionally exhibiting oil paintings at the Royal Academy and the British Institution. His oils often share the same subjects and compositional preferences as his watercolours, favouring broad handling and atmospheric effects. However, they never achieved the same level of recognition or influence as his works on paper. Today, he is overwhelmingly remembered and celebrated as a master watercolourist.

His influence also extended through his teaching. De Wint took on pupils, often instructing amateurs from wealthy families during the summer months. This activity not only provided income but also helped disseminate his approach to landscape painting. His methods emphasized direct observation and the mastery of broad wash techniques.

Representative Works: Capturing the Essence

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Peter De Wint's style and subject matter. Lincoln Cathedral from the Brayford Pool (examples in the Tate, V&A, and Usher Gallery, Lincoln) is perhaps his most iconic subject. These views typically show the vast expanse of the Brayford Pool (a natural lake on the River Witham) in the foreground, reflecting the sky, with the city and the magnificent cathedral rising on the hill beyond. The low horizon and expansive sky are characteristic, as is the harmonious balance between water, land, and architecture.

Harvest Time, Lancashire (Victoria and Albert Museum) is a superb example of his agricultural scenes. It depicts workers gathering sheaves of corn in a wide, sunlit field under a dramatic sky. The composition is broad and stable, the figures integrated naturally into the landscape, conveying the heat and labour of the harvest season with remarkable atmospheric truth. Similar qualities are found in numerous works titled Cornfield or Haymaking.

View on the River Dart, Devon showcases his ability to capture the lushness and tranquility of river scenery outside his usual Lincolnshire haunts. The handling of reflections in the water and the rich greens of the foliage demonstrate his mastery of watercolour technique. His views in Yorkshire, Wales, and the Lake District, such as Langdale Pikes, Westmorland, show his response to more undulating or mountainous terrain, though still rendered with his characteristic breadth and atmospheric sensitivity.

View of Oxford from the West is a fine example of his townscapes, combining architectural detail with a panoramic landscape setting. He captures the famous skyline of Oxford's spires and towers nestled within the surrounding countryside. His depictions of ruined structures like Kenilworth Castle tap into the Picturesque taste of the era, but are rendered with his typical restraint and focus on light and atmosphere rather than overt romantic drama. These works, among many others held in major collections like the British Museum, Tate Britain, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and regional galleries like the Usher Gallery in Lincoln, solidify his reputation.

Personal Life and Connections

Peter De Wint's personal life appears to have been relatively stable and centred around his family and his art. His marriage to Harriet Hilton in 1810 was a significant event, strengthening his ties to the Hilton family and providing the crucial connection to Lincolnshire that would so enrich his work. He maintained a lifelong, close friendship with his brother-in-law, William Hilton RA. The two artists sometimes sketched together, and their careers, though focused on different genres (landscape vs. history painting), ran in parallel within the London art world.

De Wint and his wife primarily resided in London, at 40 Upper Gower Street, where he maintained his studio. However, they made frequent, often annual, visits to Harriet's family home in Lincoln, particularly during the summer months, which were De Wint's prime sketching season. He also owned property near Lincoln later in life. These regular immersions in the Lincolnshire landscape were fundamental to his artistic practice.

He seems to have been a respected figure within the art community, known for his dedication to his craft and his amiable personality. His role as a teacher brought him into contact with patrons and amateur artists. Unlike some of his contemporaries, such as the famously competitive Turner or the financially often-struggling Constable, De Wint appears to have managed a successful and relatively untroubled professional career, finding consistent patronage for his distinctive watercolours. Contemporaries like William Henry Hunt, known for his detailed still lifes and rustic figures, occupied different niches within the watercolour market. De Wint's broad landscapes offered a different, but equally popular, vision of England.

Later Years and Legacy

Peter De Wint continued to paint and exhibit prolifically throughout the 1830s and 1840s, maintaining the high quality and distinctive style that had brought him success. He remained a stalwart of the Society of Painters in Water Colours, his works eagerly anticipated at their annual exhibitions. His vision of the English landscape, emphasizing its breadth, fertility, and quiet harmony, resonated with audiences seeking reassurance and stability in an era of rapid industrial and social change.

His health began to decline in his later years. Peter De Wint died at his home in Upper Gower Street, London, on January 30, 1849, at the age of 65. His death was attributed to heart disease. He was buried in the graveyard of the Savoy Chapel (the Chapel Royal of the Savoy) off the Strand. His wife Harriet survived him, as did their daughter, Helen Harriet De Wint.

Following his death, a major sale of the contents of his studio was held at Christie's auction house in May 1850. This sale comprised hundreds of watercolours and sketches, revealing the full scope of his life's work and further enhancing his posthumous reputation. His works were already held in significant private collections and began to enter public museums in greater numbers.

Peter De Wint's legacy lies in his unique contribution to the English landscape tradition. He perfected a style of watercolour painting characterized by breadth, atmospheric truth, and harmonious composition. His depictions of the English Midlands, particularly Lincolnshire, remain defining images of that region. While perhaps lacking the revolutionary impact of Turner or Constable, his work represents a powerful and enduring strand within British Romanticism, one focused on the quiet beauty and stability of the native landscape. He influenced subsequent generations of watercolourists, and his work continues to be admired for its technical mastery, its profound connection to place, and its serene, contemplative beauty. Artists like Richard Parkes Bonington, though younger and with a different touch, shared a similar dedication to landscape and watercolour, reflecting the vitality of the medium De Wint championed. His position as one of the key figures of the 'Golden Age' of English watercolour is secure.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Peter De Wint occupies a significant and respected place in the history of British art. As a master of watercolour, he developed a distinctive and influential style, perfectly suited to capturing the expansive landscapes and subtle atmosphere of the English countryside. His broad washes, harmonious compositions, and sensitive rendering of light created images of enduring tranquility and beauty. Through his long association with the Society of Painters in Water Colours and his consistent output of high-quality work, he helped elevate the status of the medium. His depictions of Lincolnshire, the Thames Valley, and other regions remain iconic representations of rural England in the early nineteenth century. Though influenced by Dutch masters and contemporary trends, De Wint forged a personal vision that celebrated the quiet dignity and peaceful harmony of the natural world, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with viewers today.