Pieter Balten, a significant yet sometimes overshadowed figure of the South Netherlandish Renaissance, carved a multifaceted career as a painter, printmaker, engraver, and publisher. Active primarily in Antwerp during a vibrant and transformative period in European art, Balten's contributions to landscape and genre painting, as well as to the burgeoning print market, mark him as an artist of considerable talent and influence. His life and work offer a fascinating window into the artistic currents of the 16th century, particularly his complex relationship with the towering figure of Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Antwerp

Born around 1525-1527 in Antwerp, a bustling metropolis and a leading center for art production and trade in Europe, Pieter Balten, also known by variants of his name such as Pieter Baltens or Pieter de Costere, was immersed in an artistic environment from a young age. His father, Balten Jansz. de Costere, was a sculptor, suggesting that Pieter's initial exposure to the visual arts likely came from within his own family. This familial connection to the craft would have provided him with an early understanding of artistic materials and practices, a common pathway for many artists of the era.

Antwerp, during Balten's formative years, was a crucible of artistic innovation. The city attracted artists from across the Low Countries and beyond, fostering a competitive yet collaborative atmosphere. The Guild of Saint Luke, the city's powerful organization for painters, sculptors, and other craftsmen, played a pivotal role in regulating the art trade and maintaining standards of quality. It was into this established system that Balten sought entry. In 1550, a significant milestone in his career, Pieter Balten was officially registered as a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke. This recognition not only legitimized his status as an independent artist but also allowed him to take on apprentices and sell his works openly.

His ascent within the Guild continued, culminating in his election as its dean (deken) in 1569. This prestigious position underscored his standing among his peers and his commitment to the artistic community of Antwerp. Serving as dean involved administrative responsibilities and representing the interests of the Guild, indicating a level of respect and trust afforded to him by fellow artists. This period of leadership would have further integrated him into the city's artistic and social fabric.

Artistic Style and Technical Prowess

Pieter Balten developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by a rapid yet delicate touch, particularly evident in his landscape and genre scenes. He was proficient in both watercolor (often on linen, a common practice for more affordable or preparatory works) and oil painting, demonstrating versatility in his choice of media. His oil paintings often feature thin, almost translucent layers of paint, allowing for subtle gradations of color and light. This technique, combined with visible, fluid brushstrokes, imparted a sense of immediacy and liveliness to his compositions.

A notable characteristic of Balten's technique was what contemporary sources, including the art historian Karel van Mander, described as a "veerdrige" or "feathery" manner of painting, implying a swift and light execution. This approach allowed him to capture the fleeting moments of daily life and the ephemeral qualities of nature with remarkable skill. His landscapes, for instance, often convey a strong sense of atmosphere, with carefully rendered skies and a keen observation of light and shadow.

In terms of color palette, Balten often favored earthy tones, particularly browns, which lent a rustic and authentic feel to his rural scenes. These were frequently complemented by greens in the foreground and middle ground, depicting foliage and fields, while distant vistas might recede into cooler blues and grays, a common convention in Netherlandish landscape painting to create aerial perspective. This systematic use of color helped to structure his compositions and enhance the illusion of depth. He was adept at depicting the "naar het leven" (from life) aesthetic that was gaining prominence, striving for a sense of realism in his portrayal of figures and their environments.

Thematic Focus: Landscapes and Genre Scenes

Pieter Balten's oeuvre is dominated by two interconnected themes: landscape and genre scenes. He excelled in depicting the countryside of the Low Countries, with its characteristic flat terrain, winding rivers, and clusters of farmhouses. These were not merely topographical records but often imbued with a sense of human presence and activity. His landscapes frequently serve as settings for everyday life, bridging the gap between pure landscape and genre painting.

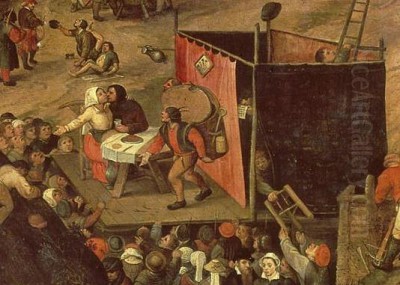

Genre scenes, particularly those depicting peasant life, kermesses (village fairs), and festive gatherings, form a significant part of his output. These works are teeming with figures engaged in a variety of activities – dancing, feasting, drinking, playing games, and interacting in lively, sometimes boisterous, ways. Balten captured the energy and spirit of these communal events with a keen eye for detail and human behavior. His depictions of kermesses, such as the celebrated St. Martin's Day Kermis, are vibrant panoramas of rural life, offering both entertainment and, at times, a subtle moral commentary, a common feature in the art of his contemporaries like Pieter Aertsen and Joachim Beuckelaer, who were pioneers in market and kitchen scenes.

The tradition of depicting peasant life had roots in earlier Netherlandish art, notably in the work of Hieronymus Bosch, but it gained new prominence in the 16th century. Balten, alongside Pieter Bruegel the Elder, was instrumental in popularizing these themes, which resonated with a growing urban audience interested in depictions of rural simplicity and folk traditions. These scenes often celebrated the cycles of nature and agricultural life, reflecting a deep connection to the land.

Key Masterpieces and Their Significance

Several works stand out in Pieter Balten's oeuvre, showcasing his artistic skill and thematic preoccupations.

St. Martin's Day Kermis: This is arguably Balten's most famous work and exists in versions held by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp. The painting is a sprawling, energetic depiction of a village festival celebrating Saint Martin's Day. It is filled with numerous figures engaged in revelry, feasting, and various forms of entertainment. The composition is dynamic, leading the viewer's eye through a multitude of anecdotal scenes. While often compared to, and sometimes considered a free adaptation of, works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder on similar themes, Balten's version has its own distinct character, emphasizing the communal spirit and perhaps a slightly less satirical tone than some of Bruegel's peasant scenes. The lively depiction of figures and the detailed rendering of the village setting are hallmarks of Balten's style.

Landscape with Peasant Cottages (1581): This painting, dated towards the latter part of his career, exemplifies Balten's mastery of landscape. It typically depicts a tranquil rural scene, perhaps with a farmhouse near a body of water, set against a backdrop of a flat plain and a distant church spire. Such works highlight his ability to create atmospheric depth through careful color gradation and his skill in rendering the textures of the natural world and rustic architecture. The use of thin, even layers of paint and a predominantly brownish palette is characteristic.

The Parable of Wheat and Tares: Considered one of Balten's most important landscape paintings, this work illustrates a biblical parable, a common practice in Netherlandish art where religious or moralizing themes were often embedded within detailed contemporary settings. The painting would have showcased Balten's ability to create a complex, panoramic landscape, integrating numerous figures and narrative elements into a cohesive whole. Such works demonstrate not only his technical skill but also his capacity for sophisticated iconographic programs.

Ecce Homo: While primarily known for landscapes and genre scenes, Balten also tackled religious subjects. An Ecce Homo by his hand would depict Christ presented to the crowd. This subject was popular, allowing artists to explore themes of suffering, justice, and human fallibility, often set within elaborate architectural or urban environments. Balten's treatment would likely reflect the influence of contemporary religious painting in Antwerp, possibly showing connections to the Bruegel family's approach to such themes.

Spring Driving Out Winter: This allegorical subject, representing the changing seasons, was also treated by Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Art historical analysis suggests that Balten's version of this theme may possess a unique character and perhaps even a degree of originality that challenges the notion of him being a mere imitator. Such works highlight the interplay of ideas and motifs among artists of the period.

Peasant Fair in a Village Square: Similar in theme to the St. Martin's Day Kermis, this work, also found in the Rijksmuseum, would depict a bustling village square filled with peasants engaged in commerce and celebration. These paintings are valuable historical documents, offering insights into the social customs, attire, and daily life of the 16th-century Low Countries.

The Bruegel Connection: Influence and Independence

The relationship between Pieter Balten and Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569) is a central and complex aspect of Balten's art historical assessment. For a long time, Balten was primarily viewed as a follower or imitator of Bruegel, who was undoubtedly the preeminent master of peasant genre and innovative landscape painting in their shared era. Indeed, there are undeniable similarities in their subject matter – kermesses, peasant dances, proverbs, and expansive landscapes – and Balten did produce versions of some of Bruegel's compositions.

However, recent scholarship has sought a more nuanced understanding of their relationship. It is crucial to note that Balten became a master in the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke in 1550, a year before Bruegel achieved the same status in 1551. This chronological fact suggests that Balten was already an established artist when Bruegel was formally entering the profession in Antwerp. Furthermore, there is documented evidence of their collaboration. In 1550-1551, Balten and Bruegel worked together on the central panel of an altarpiece (now lost) for the Glovemakers' Guild in Mechelen. This collaboration implies a relationship of peers rather than a simple master-follower dynamic, at least in these early stages of Bruegel's Antwerp career.

While Bruegel's innovative compositions and profound human insights undoubtedly had a significant impact on many artists, including Balten, it is more accurate to see Balten as an independent artist working within a shared artistic milieu. He absorbed influences from various sources, including the broader Netherlandish tradition of landscape painting pioneered by artists like Joachim Patinir and Herri met de Bles, and the burgeoning interest in genre scenes. Balten developed his own stylistic traits, such as his "veerdrige" brushwork and particular color harmonies. His interpretations of shared themes, like the St. Martin's Day Kermis or Spring Driving Out Winter, often exhibit a distinct character, sometimes more focused on the anecdotal and decorative aspects of the scene.

The tendency to label artists as "followers" of a more famous contemporary can sometimes obscure their individual contributions. In Balten's case, while the Bruegelian influence is undeniable and significant, his own artistic identity, technical skill, and the sheer volume of his production affirm his status as a noteworthy artist in his own right.

Collaborations and Contemporaries

Pieter Balten was an active participant in the vibrant artistic community of Antwerp and beyond. His collaboration with Pieter Bruegel the Elder on the Mechelen altarpiece is the most well-documented instance, but his interactions with other artists were also part of his professional life.

He is known to have been a poet and a rhetorician (rederijker), participating in the literary and dramatic activities of the chambers of rhetoric, which were important cultural institutions in the Low Countries. In this capacity, he reportedly collaborated with Cornelis Ketel (1548-1616), a Dutch painter who also worked in England and France and was known for his portraits and allegorical works. This connection highlights Balten's engagement with broader cultural pursuits beyond painting.

There is art historical speculation that Balten may have collaborated with landscape specialists like Roelant Savery (1576-1639) and Jacob Savery the Elder (c. 1566-1603), though the Saverys belong to a slightly later generation, making direct collaboration on major projects less likely unless it was earlier in their careers or with Jacob Savery the Elder. However, the interconnectedness of artistic workshops often led to various forms of collaboration, including the addition of figures to landscapes painted by specialists, or vice versa.

The artistic environment of Antwerp was rich with talent. Besides Bruegel, Balten's contemporaries included prominent figures like Frans Floris (c. 1519-1570), a leading history painter who introduced a Romanist style to Antwerp; Marten van Cleve (c. 1527-1581), another painter of peasant scenes and kermesses, whose work often shares thematic similarities with Balten's; and Jan Sanders van Hemessen (c. 1500-c. 1566), known for his genre scenes with moralizing undertones and religious paintings. The landscape tradition was also strong, with artists like Lucas van Valckenborch (c. 1535-1597) and his brother Marten van Valckenborch (1535-1612) producing panoramic views and seasonal depictions. Balten's work should be seen within this dynamic context of shared themes, stylistic exchanges, and friendly rivalries. His association with Hans Wecheman in the Mechelen painters' guild further illustrates his network within the artistic community.

The influence of earlier masters like Esaias van de Velde (c. 1587-1630) is sometimes mentioned in relation to Balten, but given Van de Velde's birth date, this would be an anachronism if suggesting Van de Velde influenced Balten. It is more likely that Balten's work, as part of the 16th-century landscape tradition, contributed to the foundations upon which later artists like Van de Velde built the Dutch Golden Age landscape.

Balten as Printmaker and Publisher

Beyond his activities as a painter, Pieter Balten was also significantly involved in the printmaking industry, both as an engraver and as a publisher. Antwerp was a major European center for print production, with publishers like Hieronymus Cock playing a crucial role in disseminating artistic ideas and images across the continent. Balten's engagement in this field demonstrates his entrepreneurial spirit and his understanding of the commercial potential of prints.

His own engravings often mirrored the themes found in his paintings – landscapes, peasant scenes, and allegorical subjects. Prints allowed for wider distribution of his compositions than unique paintings, reaching a broader audience and potentially enhancing his reputation. As a publisher, he would have commissioned other artists to create designs or engrave plates, managing the production and sale of prints. This dual role as creator and entrepreneur was not uncommon among successful artists of the period.

His son, Dominicus Custos (born Pieter Balten the Younger, c. 1560-1612), followed in his footsteps, becoming a renowned engraver and publisher, primarily active in Augsburg, Germany. Dominicus Custos is particularly known for his portrait engravings and his continuation of the family's involvement in the print trade, indicating that Pieter Balten's legacy extended through his family's artistic endeavors.

Personal Life and Character

Information about Pieter Balten's personal life is relatively scarce, as is common for many artists of his time. The art historian Karel van Mander, in his "Schilder-boeck" (Book of Painters) of 1604, provides some biographical details. Van Mander praises Balten as a "good painter" and notes his skill in depicting landscapes "in water-colours as well as in oils, very quickly and subtly."

However, Van Mander also includes a less flattering anecdote, suggesting that Balten, despite his talent and "good nature," was prone to excessive drinking ("a bit too fond of paying his respects to Bacchus"), which led to him living in poverty in his later years. While such biographical accounts from early sources should be treated with some caution, as they sometimes relied on hearsay or aimed to create a particular narrative, this detail offers a glimpse into the human side of the artist and the potential challenges he faced. His multifaceted career as a painter, poet, rhetorician, printmaker, and publisher suggests a man of considerable energy and diverse talents. He passed away in Antwerp, likely around 1584, though some sources suggest a later date up to 1598.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Pieter Balten's legacy lies in his contribution to the development of landscape and genre painting in the Southern Netherlands during a pivotal period of artistic transformation. While often viewed in the shadow of Pieter Bruegel the Elder, his work possesses its own merits and reflects the broader artistic currents of 16th-century Antwerp.

He was a skilled and prolific artist who catered to the growing market for scenes of everyday life and depictions of the local countryside. His kermess scenes, in particular, are vibrant and detailed records of contemporary folk culture, capturing the energy and communal spirit of these events. As a landscape painter, he contributed to the Netherlandish tradition of depicting the natural world with increasing realism and atmospheric sensitivity.

His involvement in the print market as an engraver and publisher further underscores his importance. Prints played a crucial role in the dissemination of artistic styles and iconographies, and Balten's participation in this industry helped to popularize the themes and compositions he favored. The continuation of this tradition by his son, Dominicus Custos, speaks to the lasting impact of his entrepreneurial and artistic endeavors.

While auction records for Pieter Balten's works are not as extensively documented or as high-profile as those for some of his more famous contemporaries, his paintings are held in major museum collections, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, and the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp. The exhibition of works like his Fair & kermis with theatre and music at prestigious art fairs such as BRAFA (Brussels Art Fair) indicates ongoing interest and recognition within the art market. His paintings are valued for their historical importance, their charming depictions of 16th-century life, and their artistic quality.

Conclusion

Pieter Balten emerges from the historical record as a versatile and accomplished artist of the Netherlandish Renaissance. His paintings of landscapes and bustling peasant festivals, his contributions as a printmaker and publisher, and his active role within the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke paint a picture of a dynamic figure deeply embedded in the artistic and cultural life of his time. While the towering genius of Pieter Bruegel the Elder often dominates narratives of 16th-century Netherlandish art, a closer examination reveals Pieter Balten as an artist of independent merit, whose work provides valuable insights into the tastes, traditions, and artistic innovations of a remarkable era. His legacy endures in his vibrant depictions of life and landscape, offering a rich visual tapestry of the world he inhabited.