René Pierre Charles Princeteau, a name perhaps not as universally recognized as some of his contemporaries, nonetheless holds a significant place in the annals of 19th and early 20th-century French art. Born in Libourne on July 18, 1843, and passing away in Fronsac on January 31, 1914, Princeteau carved a distinguished career primarily as an animalier, a painter specializing in the depiction of animals, with a particular and profound affinity for horses and the dynamic scenes of equestrian life. His work, characterized by its meticulous detail, vibrant energy, and keen observational skill, not only earned him accolades during his lifetime but also left an indelible mark on his most famous pupil, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

Early Life and Overcoming Adversity

Princeteau's journey into the world of art was shaped from its very beginning by a profound personal challenge. Born into a prosperous family in the Gironde department of southwestern France, he was deaf and mute from birth. This circumstance, which might have isolated others, seems to have sharpened his visual senses and fostered a deep, non-verbal connection with the world around him, particularly the animal kingdom. His inability to hear or speak likely channeled his expressive energies into his art, allowing him to communicate with a unique intensity and focus through his canvases.

His family's affluence provided him with the means to pursue his artistic inclinations from a young age. The Gironde region, with its rich traditions of horsemanship and hunting, undoubtedly provided early inspiration. It was an environment where the grace, power, and spirit of horses were ever-present, themes that would dominate his artistic output throughout his life. This early immersion in an equestrian world, coupled with his heightened visual perception, laid the foundation for his future specialization.

Artistic Formation and Education

Recognizing his talent, Princeteau's family supported his formal artistic training. He initially studied sculpture in Bordeaux under Dominique Fortuné Maggesi, a notable sculptor of the period. This grounding in three-dimensional form likely contributed to the strong sense of volume and anatomical accuracy evident in his later paintings. Understanding the musculature and structure of his subjects in a sculptural sense would have been invaluable for an artist dedicated to depicting animals in motion.

His ambition, however, lay in painting. Princeteau moved to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the 19th century, to further his studies. He enrolled at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the leading art institution in France. There, he would have been exposed to the rigorous academic training that emphasized drawing from life, studying the Old Masters, and mastering anatomy. While specific records of his teachers at the École des Beaux-Arts are sometimes elusive in general summaries, it's known he associated with prominent figures. He is often mentioned as having studied under sculptors like Auguste Cain, himself a renowned animalier in sculpture, and potentially received guidance from painters in the academic tradition, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, who was a highly influential professor at the École and also known for his meticulous detail and historical scenes, sometimes featuring animals.

Some sources also suggest a period of study in Düsseldorf, Germany, which was another significant art center, particularly known for its narrative and landscape painting. This exposure to different artistic traditions and pedagogical approaches would have broadened his artistic vocabulary and technical skills, allowing him to synthesize various influences into his own distinctive style.

The Rise of an Animalier: Capturing Equine Grace

Princeteau's true passion and talent lay in the depiction of horses. He quickly established himself as a leading animalier, a genre that had a long and respected tradition in French art, with predecessors like Théodore Géricault, Carle Vernet, Horace Vernet, and contemporaries like Rosa Bonheur and Alfred de Dreux. Princeteau's work stood out for its dynamism and its ability to capture not just the physical likeness of the horse, but also its spirit and energy.

He became a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, from the 1860s onwards. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. His early submissions, such as Puce, élan monté par le D. de Langem and Le Départ pour la chasse (The Departure for the Hunt), quickly garnered positive attention. These works showcased his burgeoning skill in rendering the complex anatomy of horses in various poses and his ability to compose lively, engaging scenes.

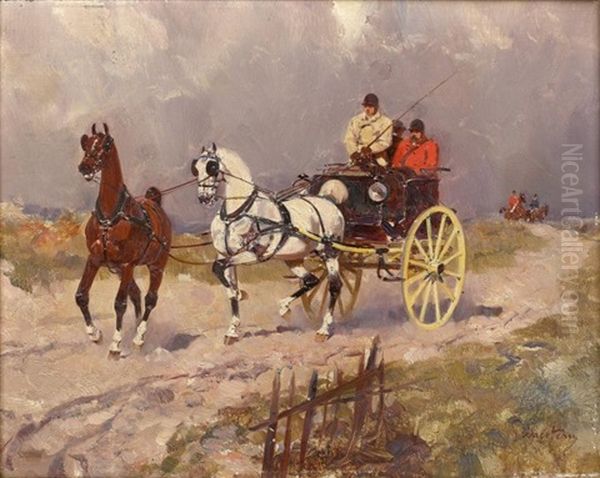

His paintings often depicted the aristocratic pursuits of the era: elegant riders, spirited hunts, racehorses thundering down the track, and military cavalry. He was adept at capturing the nuances of movement – the powerful gallop of a hunter, the prance of a well-schooled dressage horse, or the quiet grace of a horse at rest. His understanding of equine anatomy was impeccable, allowing him to portray his subjects with a convincing realism that was admired by both art critics and equestrian enthusiasts.

Artistic Style: Precision, Movement, and Atmosphere

Princeteau's artistic style was rooted in the academic tradition of careful observation and precise rendering, yet it was infused with a vitality that transcended mere technical skill. He possessed an extraordinary ability to convey the sensation of movement. His horses are rarely static; they are captured mid-stride, muscles tensed, manes and tails flowing, conveying a palpable sense of energy and speed. This was particularly evident in his hunting scenes, where the chaos and excitement of the chase were masterfully orchestrated on canvas.

His handling of light and shadow was another hallmark of his style. He used chiaroscuro effectively to model the forms of his subjects, giving them a strong sense of three-dimensionality. His understanding of how light played on the glossy coats of horses, the textures of riding attire, and the elements of the landscape added depth and realism to his compositions. He often created a specific atmosphere in his paintings, whether it was the crisp air of a morning hunt or the dusty haze of a racetrack.

While primarily a realist, there are elements in some of his works that hint at an awareness of Impressionistic concerns with light and atmosphere, particularly in his landscape settings. However, his primary focus always remained the accurate and dynamic portrayal of his animal subjects. His palette was generally rich and naturalistic, effectively capturing the varied colors of horse coats and the verdant landscapes they inhabited.

Notable Works and Thematic Concerns

Throughout his prolific career, René Princeteau produced a significant body of work, much of it centered on his beloved equine subjects. One of his most acclaimed early works was Étampe de soldats surprise par une embuscade de franco-tireurs (Patrol of Dragoons Surprised by an Ambush of Franc-Tireurs), painted in 1872. This painting, depicting a dramatic moment from the Franco-Prussian War, was lauded not only for its skilled portrayal of horses and soldiers in a moment of crisis but also for its powerful landscape, leading some to consider it a masterpiece within French landscape painting of the period. It demonstrated his ability to handle complex, multi-figure compositions and to evoke strong narrative and emotional content.

Other significant works that highlight his specialization include:

Chasse à courre (The Hunt or Hounds): A recurring theme, these paintings captured the excitement and tradition of the French stag hunt, with packs of hounds and mounted hunters in full pursuit. These works allowed him to showcase his skill in depicting multiple animals in dynamic motion.

Twenty-two Horses of Ramses and Panorama of 160 Horses: These titles suggest ambitious, large-scale compositions that would have further cemented his reputation for mastering complex equine subjects. Such works would have required immense skill in perspective, anatomy, and composition.

Riders on the Beach at Dieppe: This work, and others like Promenade sur les dunes, shows a different facet of equestrian life, capturing the leisure and elegance of riders by the sea or in scenic landscapes. These paintings often have a lighter, more atmospheric quality.

La vue (The View): Likely a landscape, perhaps featuring horses, indicating his broader interest in the natural environment that so often formed the backdrop for his equestrian scenes.

Le Tilbury: This painting, now in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, depicts a type of light, open two-wheeled carriage, showcasing his attention to the details of equestrian equipage as well as the horses themselves.

Intérieur de grange de la ferme de Pontus (Interior of the Barn at Pontus Farm, c. late 19th century) and Sur le bassin d’Arcachon (On the Arcachon Bay): These works, acquired by the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Libourne, demonstrate his versatility in depicting more rustic or serene scenes, still often connected to rural life where horses played a vital role.

Le Relais (The Relay Station): Another piece in the Libourne museum, this likely depicts a scene involving coaching or changing horses, a common sight in the 19th century and a subject rich with activity.

Princeteau's dedication to his chosen subject matter was unwavering. He explored every facet of the horse's role in human life, from sport and leisure to work and warfare, always with an eye for anatomical accuracy and expressive power.

A Profound Mentorship: Princeteau and Toulouse-Lautrec

Perhaps one of René Princeteau's most lasting legacies, beyond his own artistic achievements, was his role as the first significant art teacher and lifelong mentor to Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901). Lautrec, born into an aristocratic family (his father, Comte Alphonse de Toulouse-Lautrec, was a friend of Princeteau), was a distant cousin of Princeteau. From a young age, Lautrec showed a keen interest in drawing, often sketching horses, a passion likely fueled by his family's aristocratic pursuits and Princeteau's example.

Lautrec began receiving informal instruction from Princeteau around the age of seven or eight, often at Princeteau's Parisian studio located at 233 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré. This was a crucial formative period for the young Lautrec. Princeteau, with his own physical challenge of deafness, would have been a particularly empathetic and inspiring figure for Lautrec, who later suffered from a congenital condition that stunted his growth and left him with physical disabilities. Their shared experiences of navigating the world with physical differences likely forged a strong bond.

Princeteau encouraged Lautrec's burgeoning talent, guiding his hand and eye, and instilling in him the importance of observation and draftsmanship. Lautrec's early works clearly show Princeteau's influence, particularly in his depictions of horses and hunting scenes. Lautrec copied Princeteau's works and learned to capture the dynamism of animal movement under his tutelage. In a letter, Lautrec would later refer to Princeteau as "your faithful student," a testament to their enduring connection.

It was Princeteau who recognized the depth of Lautrec's talent and encouraged him to pursue art professionally. He played a key role in persuading Lautrec's family to allow him to undertake formal artistic training. Furthermore, Princeteau facilitated Lautrec's entry into the studio of Léon Bonnat in 1882. Bonnat was a respected academic painter, and studying with him was a significant step in Lautrec's artistic development. After Bonnat closed his teaching studio, Lautrec moved to the studio of Fernand Cormon, where he encountered fellow students like Émile Bernard and Vincent van Gogh, further expanding his artistic horizons.

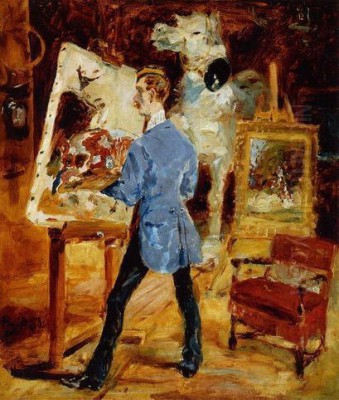

Despite Lautrec's eventual divergence into a radically different artistic style – becoming a key figure of Post-Impressionism, renowned for his depictions of Parisian nightlife, cabarets, and brothels – the foundational skills and encouragement he received from Princeteau were invaluable. The two artists remained lifelong friends, and Lautrec painted a notable portrait, Princeteau in his Studio (1881), which captures his mentor at work, surrounded by the paraphernalia of his art.

Connections and Contemporaries in the Parisian Art World

René Princeteau was an active figure in the vibrant Parisian art scene of the late 19th century. His studio was a meeting place, and his social connections extended into aristocratic circles, many of whom were his patrons. Beyond his profound relationship with Toulouse-Lautrec and Léon Bonnat, he moved within a world populated by a diverse array of artists.

While direct, deep friendships with figures like Édouard Manet (1832-1883) or Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) are not extensively documented in the provided information (which even notes a lack of direct evidence for close interaction), they were significant contemporaries. Manet, a revolutionary figure whose work bridged Realism and Impressionism, was admired by Lautrec, and their paths would have crossed in the Parisian art milieu. Cézanne, a pivotal Post-Impressionist, was also part of this broader artistic ferment. It's plausible that Princeteau, as an established Salon artist and a social figure, would have been aware of and peripherally connected to the leading artistic currents and personalities of his time, even if his own style remained more traditional.

Other notable contemporaries and figures relevant to Princeteau's world include:

Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904): A leading academic painter and influential teacher at the École des Beaux-Arts. His meticulous style and interest in historical and exotic subjects, sometimes featuring animals, would have been well-known to Princeteau.

Rosa Bonheur (1822-1899): The most celebrated female artist of the 19th century and a highly successful animalier, particularly known for The Horse Fair. She and Princeteau shared a specialization and achieved considerable fame for their depictions of animals.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917): An Impressionist master who, like Princeteau, was fascinated by horses, particularly racehorses. Degas's innovative compositions and focus on movement in his equestrian scenes offered a more modern counterpoint to Princeteau's academic approach. Lautrec greatly admired Degas.

Alfred de Dreux (1810-1860): An earlier, highly fashionable painter of horses and equestrian portraits, whose work set a high standard for the genre in the mid-19th century.

Constant Troyon (1810-1865): A prominent member of the Barbizon School, known for his landscapes and animal paintings, often depicting cattle and sheep with a naturalistic sensibility.

Ernest Meissonier (1815-1891): Immensely popular for his meticulously detailed historical and military scenes, often featuring horses rendered with great accuracy. He was a towering figure in the academic art world.

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877): The leading figure of Realism, Courbet also painted hunting scenes and animals, though with a more rugged and less idealized approach than many animaliers.

The Vernet family (Carle, Horace, Émile Jean-Horace): This dynasty of painters, spanning the late 18th to the mid-19th century, excelled in battle scenes, equestrian portraits, and depictions of Arab life, all heavily featuring horses. They were foundational to the French tradition of equestrian painting.

Théodore Géricault (1791-1824): Though from an earlier generation, Géricault's powerful and romantic depictions of horses, such as Officer of the Chasseurs Charging, remained influential for any artist tackling equine subjects.

Princeteau's engagement with this artistic environment, whether through direct collaboration, friendly acquaintance, or simply shared exhibition spaces at the Salon, contributed to the rich tapestry of 19th-century French art.

Later Years, Legacy, and Recognition in Collections

René Princeteau continued to paint and exhibit throughout his life, maintaining his focus on equestrian subjects. He was made an honorary member of the Bordeaux Art Academy, a recognition of his standing in his native region. He divided his time between Paris and his family estate at Pontus, near Fronsac in the Gironde, where he passed away in 1914 at the age of 71.

His legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he was a master of his chosen genre, creating a body of work that celebrated the beauty, power, and spirit of the horse with exceptional skill and dedication. His paintings remain highly sought after by collectors of equestrian art. As a mentor, his influence on Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was profound, providing crucial early guidance and support that helped launch one of the most iconic careers in Post-Impressionist art.

Princeteau's works are held in various public and private collections. The Musée des Beaux-Arts in his birthplace of Libourne holds a significant collection, including paintings like Le Relais, Promenade sur les dunes, Intérieur de grange de la ferme de Pontus, and Sur le bassin d’Arcachon. The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, USA, owns his painting Le Tilbury. His works also appear in auctions; for instance, Toulouse-Lautrec's portrait Princeteau in his Studio (1881) fetched $762,500 at a Bonhams auction in 2024, underscoring the art market's interest in their intertwined histories. His painting Hounds Driving Hounds (1875), originally commissioned by the Marquis de Guadalmina, later found its way into the esteemed Robert & Manuel Schmit collection. In 1994, the Galerie Schmit in Paris held an exhibition titled "Chevaux et cavaliers," dedicated to his work.

The ongoing acquisition of his works by museums and their performance in the art market attest to his enduring appeal. The Amis des Musées association in Libourne even acquired a preparatory sketch by Princeteau in 2014, highlighting the continued scholarly interest in his creative process.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

René Pierre Charles Princeteau stands as a testament to the power of focused dedication and the ability to overcome personal adversity through artistic expression. His deafness, rather than hindering him, may have amplified his visual acuity, allowing him to capture the nuances of the equine world with unparalleled precision and empathy. As a leading animalier of his time, he brought to life the elegance of the Parisian riding schools, the thrill of the hunt, and the raw energy of the racetrack. His meticulous technique, combined with a genuine love for his subjects, resulted in works that continue to captivate viewers.

Beyond his own canvases, his role in nurturing the prodigious talent of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec ensures his place in art history. Princeteau provided not just technical instruction but also crucial encouragement and friendship at a formative stage of Lautrec's life. In the grand narrative of 19th-century French art, René Princeteau remains a distinguished figure, an artist whose passion for the horse translated into a legacy of dynamic and beautifully rendered paintings, and a mentor whose guidance helped shape one of art's most unique voices. His life and work remind us that art can be a powerful means of connection, communication, and enduring influence.