Introduction: An Artist of Two Worlds

Robert Gwelo Goodman stands as a significant figure in the annals of South African art history. Born in England in 1871, he spent the most formative and productive years of his life in South Africa, becoming one of its most celebrated painters before his death in 1939. His life and work represent a fascinating intersection of European artistic training and a deep engagement with the landscapes, light, and culture of his adopted homeland. Known primarily as a landscape painter, Goodman's oeuvre also includes architectural contributions, reflecting a versatile artistic talent. His very name, incorporating "Gwelo" – the colonial-era name for Gweru in present-day Zimbabwe, hinting at a connection to Southern Africa even before his permanent settlement – speaks to the dual identity that shaped his career.

Goodman's journey took him from the railways of South Africa to the prestigious art academies of Paris, the vibrant landscapes of India, and back to a position of prominence within the South African art establishment. He navigated the challenges of establishing an artistic career across continents, adapted European techniques to capture the unique essence of the South African environment, and left a lasting legacy through his paintings, architectural designs, and influence on the artistic community. This exploration delves into the life, work, and impact of Robert Gwelo Goodman, a pivotal artist who helped shape the visual identity of South Africa.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Robert Goodman was born in Taplow, Buckinghamshire, England, in 1871. His connection to South Africa began in his youth when his family relocated due to his father's work as a railway official. This move proved decisive for his future path. Initially, Goodman followed a more conventional route, working for a time as a clerk for the railway company in South Africa. However, the artistic impulse was strong, and the unique landscapes and burgeoning society of his new home likely fueled his desire to capture the world visually.

A crucial turning point came with the encouragement of J.S. Morland, who held the distinction of being the first President of the South African Society of Artists (SASA). Recognizing Goodman's potential, Morland advised him to seek formal training in Europe. Heeding this advice, Goodman traveled to Paris in 1895, the vibrant heart of the art world at the time. This move immersed him in an environment rich with artistic innovation and tradition.

In Paris, Goodman enrolled at the renowned Académie Julian, a private art school famous for attracting international students and offering a counterpoint to the rigid École des Beaux-Arts. Here, he received rigorous instruction under prominent academic painters William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Gabriel Ferrier. Bouguereau, a master of the academic style, emphasized meticulous drawing, refined finish, and classical themes. Ferrier, also a respected figure, reinforced these traditional values. This training provided Goodman with a strong technical foundation in drawing, composition, and the handling of paint, skills evident throughout his career.

While grounded in academic tradition, Goodman's time in Paris also exposed him to the revolutionary currents of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. The works of artists like Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and others who prioritized capturing fleeting moments of light and colour were transforming the art scene. Though Goodman never fully adopted a purely Impressionistic style, the movement's emphasis on light, atmosphere, and en plein air painting undoubtedly influenced his approach, particularly in his landscape work upon returning to the distinct light conditions of Southern Africa.

Forging an Identity: Early Career and the "Gwelo" Distinction

After his formative years studying in Paris, Robert Goodman sought to establish his artistic career. He initially faced challenges gaining recognition in the competitive London art world. Sources suggest that it was during this period, finding it difficult to make headway purely as an English artist, that he strategically added "Gwelo" to his professional name. This addition served to highlight his connection to Southern Africa, lending him a degree of exoticism or distinctiveness in the British context and perhaps tapping into the colonial interest in the region. It was a conscious branding decision reflecting the complexities of identity for an artist straddling two continents.

His return to South Africa around 1901 marked the beginning of his serious engagement with the local landscape and society as his primary subject matter. The Boer War (1899-1902) was a defining event of this period, and Goodman, like other artists, contributed to the visual record of the conflict, undertaking work painting scenes related to the war. This early work demonstrated his ability to apply his skills to subjects of immediate historical relevance.

Even in these early stages, the synthesis that would define his mature style began to emerge: the combination of his solid French academic training with an increasing sensitivity to the specific atmospheric conditions and topographical features of South Africa. He started building a reputation within the country, laying the groundwork for his later prominence. His experiences moving between England and South Africa, coupled with his formal training, equipped him with a unique perspective that would soon find fuller expression.

The Indian Sojourn: A Quest for New Vistas

Seeking new subjects and perhaps opportunities, Goodman embarked on a significant journey to India between 1903 and 1904. This trip represented a deliberate effort to broaden his artistic horizons and engage with a different, equally vibrant culture and landscape. He travelled extensively across the subcontinent, visiting notable locations such as Bangalore, Jodhpur, and the picturesque city of Udaipur, known for its lakes and palaces.

During this intensive period of travel and work, Goodman was highly productive, creating approximately seventy paintings. These works captured the diverse scenery, architectural marvels, and cultural life of India. One can imagine him applying his skills in rendering light and atmosphere to the unique conditions of the Indian climate and the colourful tapestry of its street life and ceremonial events. A work like Indian Street Festival, mentioned in relation to his oeuvre, likely stems from this period, showcasing his ability to capture the energy and vibrancy of such scenes through dynamic brushwork and careful observation of light.

Despite the artistic richness of the experience and the substantial body of work produced, the Indian venture did not yield the financial success Goodman might have hoped for. He reportedly failed to secure commissions from the Indian Maharajas or significant patrons. The inability to sell these works created financial difficulties, ultimately compelling him to return to Britain. While perhaps a commercial disappointment at the time, the Indian journey undoubtedly enriched his visual vocabulary and provided him with a wealth of experiences and subjects that informed his broader artistic perspective.

Consolidation in South Africa: Recognition and Influence

Around 1915, Robert Gwelo Goodman made the decisive move to settle permanently in South Africa. This marked the beginning of the most stable and influential phase of his career. He established himself primarily in Johannesburg but also spent considerable time working in Cape Town, immersing himself fully in the country's artistic and social life. His reputation grew steadily, and he became a highly respected figure within the South African art community.

Goodman played an active role in the development of local art institutions. He was notably one of the founders of the South African Society of Artists (SASA), a key organization promoting the visual arts in the country. His involvement extended to membership in other groups, such as the Johannesburg Sketch Club. Through these affiliations, he contributed to fostering a sense of community among artists and promoting art appreciation among the public. He was part of a generation working to establish a distinctly South African artistic identity.

His advocacy extended to his artistic philosophy. Goodman encouraged fellow South African artists to turn their attention to the unique, often undocumented aspects of their own environment. He urged them to depict the local landscape with honesty and directness, moving away from overly romanticized or Europeanized interpretations. He believed in capturing the specific character of the South African light, terrain, and flora, a principle clearly reflected in his own work.

Goodman's growing stature was confirmed by international recognition. A significant achievement came in 1915 when he was awarded a Gold Medal for two drawings at the prestigious Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. This award underscored the quality of his work and helped solidify his reputation both at home and abroad. By this time, Goodman was no longer just an artist living in South Africa; he was a leading South African artist.

Artistic Style: Capturing the Essence of South Africa

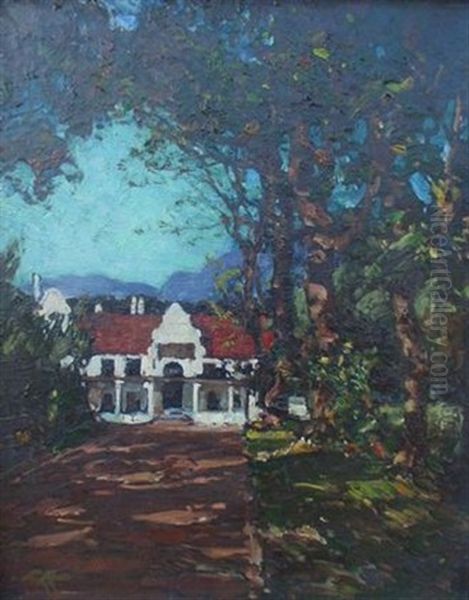

Robert Gwelo Goodman's mature artistic style is characterized by a masterful synthesis of his European training and his deep observation of the South African environment. While grounded in the academic precision learned under Bouguereau and Ferrier, his work embraced the Impressionists' fascination with light and atmosphere, adapting these principles to the unique clarity and intensity of the Southern African sun. He became particularly renowned for his landscape paintings, which captured the country's natural beauty and its colonial-era architecture with remarkable skill.

His technique involved a confident handling of paint, often using vigorous brushwork combined with areas of finer detail. He possessed a keen eye for colour and was adept at capturing the subtle variations and dramatic contrasts of light and shadow that define the South African landscape. His paintings often convey a strong sense of place and atmosphere, whether depicting the sun-drenched vineyards of the Cape, the rugged mountains, or the tranquil coastal scenes.

Several works stand out as representative of his style. Hermanus (1935) is considered a key example of his mature work. Reports suggest he reworked this painting extensively, indicating his meticulous approach and commitment to achieving a specific effect. The painting is noted for its complex brushwork and a distinctive palette featuring strong oranges and browns, capturing the specific coastal light and terrain of the popular seaside town. Sunlight on a Waterway showcases his ability to render the dazzling effects of sunlight on water, a recurring theme where his mastery of light is particularly evident. Even in still life, such as Still with Roses (1935), his sensitivity to light, texture, and composition is apparent.

Goodman's contribution lay not just in his technical skill but in his ability to see and interpret the South African landscape with fresh eyes. While contemporaries like J.H. Pierneef developed a more stylized and monumental vision of the land, Goodman focused on capturing its atmospheric qualities and picturesque aspects, often with a warmth and immediacy that resonated widely. His work provided a touchstone for realistic landscape painting in South Africa, influencing subsequent generations of artists. Other contemporaries whose work provides context include the early Cape Impressionists like Pieter Wenning and Hugo Naudé, and later figures like Maggie Laubser and Irma Stern, though their styles moved towards Expressionism.

Architectural Pursuits: The "Gwelo Colonial" Style

Beyond his prolific output as a painter, Robert Gwelo Goodman also made notable contributions in the field of architecture, demonstrating a remarkable breadth of artistic talent. His architectural work is particularly associated with the Tongaat Hulett sugar estate in KwaZulu-Natal, where he was commissioned in 1936 to undertake significant design work. This venture allowed him to translate his artistic sensibilities into three-dimensional form, leaving a lasting physical imprint on the landscape.

At Tongaat, Goodman was responsible for designing key structures, including the main facade and gardens of the Amanzimyama residence complex. His work there is often described as embodying the "Gwelo Colonial" style. This style appears to be a personal interpretation and adaptation of colonial architectural idioms, likely drawing inspiration from Cape Dutch and British colonial precedents but infused with Goodman's own aesthetic preferences. It suggests a blend of traditional forms with attention to proportion, setting, and perhaps a certain picturesque quality, echoing his landscape paintings.

His architectural designs were noted not just for their aesthetics but also for an apparent consideration of the social context. The reference to social sustainability in relation to his Tongaat work suggests an awareness of the living conditions and community aspects associated with the estate's development. This aligns with broader movements in architecture and planning during the period that began to consider the social responsibilities of design. His work can be seen in the context of the Cape Dutch Revival, a style popular in the early 20th century, championed by architects like Herbert Baker, which sought to adapt historical forms for modern use. Goodman's contribution adds a unique artistic perspective to this architectural landscape.

Interactions, Influences, and the Artistic Milieu

Robert Gwelo Goodman's career unfolded within a dynamic network of artistic relationships and influences. His foundational training under the French academicians William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Gabriel Ferrier provided him with essential skills, while his exposure to Impressionism in Paris broadened his understanding of light and colour. The early encouragement from J.S. Morland, a key figure in the South African Society of Artists (SASA), was pivotal in directing him towards formal European study.

Upon establishing himself in South Africa, Goodman became an active participant in the local art scene. His role as a co-founder of SASA and member of the Johannesburg Sketch Club placed him in regular contact with fellow artists. While specific details of collaborations might be scarce, his prominent position suggests ongoing dialogue and exchange within these circles. He was a contemporary of major figures in South African art, including landscape painters like J.H. Pierneef, Pieter Wenning, and Hugo Naudé, although their stylistic paths often diverged.

There is mention of direct interaction with the British artist Fred Appleyard. Both artists shared an interest in capturing light and colour, suggesting potential for mutual influence or shared sensibilities, reflecting the connections between the British and South African art worlds at the time. Goodman's advocacy for depicting authentic South African scenes undoubtedly influenced younger artists looking to forge a local identity, steering them away from purely European conventions.

His international exhibitions and the Gold Medal win in San Francisco brought his work to a wider audience, placing South African art within a global context. Furthermore, the support he received from collectors both in South Africa and internationally attests to his broad appeal and recognized status. His engagement with architectural design, particularly the Tongaat project, also brought him into contact with different professional circles, further extending his influence beyond easel painting.

Challenges and the Realities of an Artist's Life

Despite his eventual success and recognition, Robert Gwelo Goodman's career was not without its challenges and difficulties, reflecting the often precarious nature of life as a professional artist. His early struggles to gain a foothold in the London art market, which led to the strategic adoption of "Gwelo" in his name, highlight the competitive environment artists faced and the importance of differentiation.

Financial pressures were also a reality. The anecdote about his unsuccessful trip to India in 1903-04, where he produced a large body of work but failed to secure sales or commissions from the Maharajas, forcing his return to Britain, underscores the economic uncertainties inherent in artistic pursuits. There are also reports suggesting that at times, due to lack of financial support from patrons for exhibitions, he was forced to wash down canvases for reuse – a stark illustration of the material constraints artists could face.

While he became a celebrated figure, navigating the expectations of patrons, critics, and the public would have presented ongoing challenges. His advocacy for a truthful depiction of the South African landscape, rather than a romanticized version, might have met with resistance from some quarters accustomed to more idealized European conventions. Maintaining artistic integrity while achieving commercial success is a perennial balancing act for artists, and Goodman likely navigated these tensions throughout his career. These challenges provide a more nuanced understanding of the dedication and resilience required to sustain a long and productive artistic life.

Legacy and Enduring Appeal

Robert Gwelo Goodman died in 1939, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant legacy within South African art and culture. He is remembered as one of the country's foremost landscape painters, admired for his technical proficiency, his sensitivity to light and atmosphere, and his ability to capture the distinctive character of the South African scene. His work successfully bridged European artistic traditions and local subject matter, contributing significantly to the development of a national school of painting.

His influence extended beyond his own canvases. Through his involvement in art societies like SASA and his advocacy for depicting local realities, he helped shape the direction of South African art during a crucial period of its development. His foray into architecture, particularly the "Gwelo Colonial" style developed for the Tongaat Hulett estate, represents a unique, tangible contribution to the country's built heritage. The fact that his former residence is recognized as a cultural heritage site further attests to his lasting importance.

Goodman's paintings remain highly sought after by collectors. His works continue to perform well when they appear at auction, with pieces like Still with Roses achieving notable prices, indicating sustained appreciation for his artistry. Major South African art galleries and museums hold his work in their collections, ensuring its accessibility to future generations. He stands as a key figure for understanding the evolution of South African art in the first half of the 20th century, representing a vital link between academic training, Impressionist sensibilities, and the authentic portrayal of the nation's identity.

Conclusion: A Master of Light and Place

Robert Gwelo Goodman's life and career offer a compelling narrative of artistic dedication and cultural synthesis. From his beginnings in England and early life in South Africa to his rigorous training in Paris and his extensive travels, he absorbed diverse influences that he skillfully integrated into a unique artistic vision. His decision to settle permanently in South Africa and devote his considerable talents to depicting its landscapes and architecture marked him as a foundational figure in the country's art history.

His mastery of light, confident brushwork, and keen observational skills allowed him to capture the essence of South Africa with both accuracy and evocative power. Whether painting the sunlit vineyards, the rugged coastline, or the vibrant street life of India, Goodman demonstrated a consistent ability to convey atmosphere and a strong sense of place. His contributions to architecture further highlight his versatility and his engagement with the physical and social fabric of his adopted homeland.

Though he faced challenges, Goodman's perseverance and talent earned him widespread recognition during his lifetime, a reputation that endures today. His work remains a testament to the beauty he found in the South African environment and his commitment to portraying it authentically. As an artist who successfully navigated multiple cultural contexts and artistic traditions, Robert Gwelo Goodman leaves a rich legacy as a master painter and a significant contributor to the visual identity of South Africa.