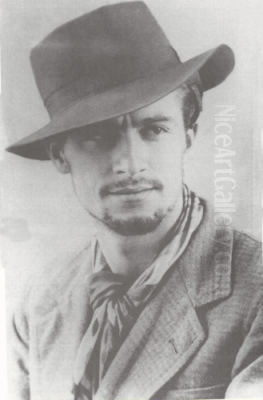

Romualdo Locatelli, a name that resonates with artistic brilliance and an unsolved mystery, stands as a fascinating figure in early 20th-century art. An Italian painter of considerable talent and a restless spirit, his life was a vibrant tapestry woven with threads of European tradition, modernist experimentation, and an insatiable curiosity for the exotic. His journey took him from the artistic heartlands of Italy to the sun-drenched landscapes of North Africa and, ultimately, to the captivating cultures of Southeast Asia. Locatelli's story is not just one of artistic achievement but also of a life cut tragically short, leaving behind a legacy of powerful imagery and an enduring enigma.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born on April 4, 1905, in Bergamo, a picturesque town in northern Italy renowned for its rich artistic heritage, Romualdo Locatelli was seemingly destined for a life in art. He was the eldest son of Luigi Locatelli, a respected decorative painter and fresco artist. The Locatelli household was steeped in creativity, with Romualdo's brothers, Raffaello Locatelli, Stefano Locatelli, and Aldo Locatelli, also pursuing artistic careers. This familial environment undoubtedly nurtured his innate talents from a very young age.

His prodigious abilities became evident early on. By the tender age of eleven, Romualdo was already immersed in formal art lessons, a testament to his precocious skill and dedication. His apprenticeship began in earnest when, at just fourteen, he was assisting his father, Luigi, in the significant task of decorating the San Filaso church. This hands-on experience provided him with invaluable practical knowledge of large-scale composition and traditional techniques, a foundation that would serve him well throughout his diverse career.

To further hone his craft, Locatelli enrolled in the prestigious Accademia Carrara in Bergamo, an institution that has trained generations of Italian artists. His quest for artistic excellence then led him to Milan, where he deepened his studies at the esteemed Palazzo di Brera, also known as the Brera Academy. These formative years provided him with a rigorous academic grounding, mastering the fundamentals of drawing, anatomy, and composition, skills evident even in his later, more expressive works.

The Italian Sojourn: Forging a Reputation

With his academic training complete, Romualdo Locatelli embarked on his professional career, initially establishing himself within Italy. His talent did not go unnoticed, and he began to build a reputation for his skillful portraiture and dynamic compositions. His early work, while rooted in academic tradition, already hinted at a burgeoning modernist sensibility. He was not content to merely replicate reality; instead, he sought to capture the essence and character of his subjects and scenes.

His artistic explorations soon extended beyond the Italian mainland. Locatelli undertook creative journeys to Tunisia in North Africa, as well as to the Italian islands of Sardinia, and the regions of Tuscany and Veneto. These travels exposed him to diverse cultures, landscapes, and light conditions, enriching his visual vocabulary and influencing his palette. The vibrant colors and distinct atmospheres of these locales began to permeate his work, adding new dimensions to his evolving style.

During this period, Locatelli gained recognition as a portraitist of notable figures. He was commissioned to paint members of the Italian aristocracy and prominent political figures. Among his sitters were members of the Italian royal family, including King Victor Emmanuel III. According to some accounts, his patrons even included high-ranking ecclesiastical figures, with mentions of a portrait for Pope Benedict XIII, though the pontificate of Benedict XIII (1724-1730) predates Locatelli significantly, suggesting a possible reference to a later pontiff or a commission involving a historical depiction. Regardless of the specific identities, these commissions underscored his growing stature in the Italian art world.

A Modernist Eye: Style and Technique

Romualdo Locatelli's artistic style was characterized by a dynamic energy and a distinctly modern approach. While his early training was academic, he quickly moved towards a more expressive and personal visual language. His brushwork was often rapid and confident, imbuing his canvases with a sense of immediacy and vitality. This gestural quality, combined with a sophisticated understanding of form and color, set him apart from many of his more conservative contemporaries.

He demonstrated a clear inclination towards modernist aesthetics, simplifying forms and emphasizing emotional impact over meticulous detail. His color palette often favored whites and mineral tones, creating a luminous, sometimes stark, effect that was both bold and sophisticated. This was particularly evident in his "Orientalist" themed works, where he sought to capture the unique light and atmosphere of the East. Artists like Henri Matisse had earlier explored the vibrant colors of North Africa, and while Locatelli's palette was often more subdued, the influence of modernist explorations of color and form is apparent.

His portraits were not mere likenesses; they were insightful character studies. He had a remarkable ability to convey the personality and inner life of his subjects through subtle nuances of expression and posture. This psychological depth, combined with his vigorous technique, made his portraits compelling and memorable. His approach can be seen as part of a broader European trend in portraiture, where artists like Amedeo Modigliani, with his elongated forms, or Giovanni Boldini, with his flamboyant society portraits, were also pushing the boundaries of the genre, albeit in different stylistic directions.

The Allure of the Orient: Travels in the East Indies

The late 1930s marked a pivotal chapter in Locatelli's life and career: his journey to the East. Drawn by the allure of distant lands and cultures, he traveled extensively through the Dutch East Indies (present-day Indonesia) and Malaya (part of present-day Malaysia). This period was immensely productive and saw a significant evolution in his art. The exotic landscapes, vibrant cultures, and unique quality of light in Southeast Asia provided a rich new source of inspiration.

His time in Bali was particularly transformative. The island, already a magnet for Western artists like Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet, who had established a unique artistic dialogue with local traditions, captivated Locatelli. He produced numerous works depicting the Balinese people, their ceremonies, and the lush tropical environment. These paintings are characterized by their sensitivity and an attempt to capture the spirit of the place, moving beyond mere ethnographic recording. He was fascinated by the grace and dignity of the local inhabitants, and his portraits from this period are among his most celebrated works.

Locatelli's paintings from the East Indies showcased his modernist tendencies, as he adapted his style to convey the intensity of the tropical light and the richness of the local color. His works were exhibited in key colonial centers such as Bali and Singapore, where they were well-received, further cementing his reputation as an artist of international standing. He joined a lineage of European artists, from Eugène Delacroix in the 19th century to contemporaries like Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merprès (also active in Bali), who found profound inspiration in non-Western cultures, contributing to the complex genre of Orientalism.

Collaborations and Connections

Throughout his career, Romualdo Locatelli engaged with other artists, both through formal collaborations and by participating in the broader artistic discourse of his time. His family background, with a father and brothers also active as artists, naturally fostered an environment of artistic exchange. His brother, Aldo Locatelli, for instance, also became a renowned painter, particularly known for his later work in Brazil. One notable collaboration involved Romualdo painting the "Ultima Cena" (Last Supper) fresco for the Igreja de São Pelegrino in Caxias do Sul, Brazil, a church where Aldo also contributed significant artworks.

During his time in Southeast Asia, he is known to have worked alongside fellow Italian painter Emilio Sessa on mural projects. In the Philippines, where he spent his final years, he collaborated with another Italian artist, Emilio Amari. These partnerships highlight a willingness to engage in collective artistic endeavors, particularly in the realm of large-scale decorative works and murals, a field in which his father, Luigi Locatelli, had initially trained him.

His participation in the prestigious Venice Biennale in 1936, where he exhibited portraiture, placed him firmly within the mainstream of contemporary European art. The Biennale was a crucial platform for artists to showcase their work to an international audience and to engage with the latest artistic trends. It was a space where Italian modernists like Giorgio de Chirico or Carlo Carrà also made their mark.

An intriguing, though chronologically challenging, aspect of his reported commissions involves the architect Filippo Juvarra. Some accounts suggest Locatelli was commissioned by Juvarra to create large perspective views for Vittorio Amedeo II, depicting the Castello di Cospaia. Given that Juvarra and Vittorio Amedeo II were prominent figures of the early 18th century, this suggests either a commission to create historical reconstructions or a possible confusion with other patrons or projects. Nevertheless, the mention points to Locatelli's skill in architectural rendering and large-scale compositions.

Notable Commissions and Patrons

Romualdo Locatelli's talent attracted a distinguished clientele throughout his career. His skill in portraiture, in particular, led to commissions from the highest echelons of society. As mentioned, he painted portraits for members of the Italian royal family, including King Victor Emmanuel III. Such patronage was a significant endorsement of an artist's status and ability during that era.

His work for ecclesiastical institutions, such as the early assistance to his father at the San Filaso church and the later "Ultima Cena" fresco in Brazil, demonstrates his capacity for religious art and large-scale mural painting. These projects required not only technical skill but also an understanding of iconographic traditions and the ability to create works that resonated within sacred spaces.

The commissions he undertook in the East Indies, though perhaps less formally documented in accessible Western records, would have included portraits of colonial officials, wealthy expatriates, and possibly local dignitaries. His exhibitions in Singapore and Bali suggest a market for his work among the European communities and art connoisseurs in the region. Artists like Locatelli, with their European training and modernist sensibilities, offered a unique perspective that was highly valued.

The Man Behind the Canvas: Personality and Anecdotes

Beyond his artistic achievements, Romualdo Locatelli was known for his distinctive, somewhat eccentric personality. He married Erminia at the relatively young age of twenty, and she remained a significant figure in his life, accompanying him on his travels, including the fateful final journey to the Philippines.

Anecdotes suggest a man who was perhaps unconcerned with strict social conventions. One often-recounted story tells of his rather informal attire when meeting King Vittorio Emanuele III, an occasion where most would have adhered rigidly to protocol. This suggests a confident, perhaps even bohemian, character, focused more on his art and personal expression than on societal expectations. Such traits were not uncommon among artists of the period, who often cultivated an image of individuality, akin to figures like Tamara de Lempicka with her glamorous and assertive persona.

His decision to travel extensively, particularly to Southeast Asia, also speaks of an adventurous and curious spirit. This was not a common path for many European artists of his generation, indicating a desire to break from convention and seek out new experiences and inspirations far from the established art centers of Europe.

Tragically, there was also a shadow in the family's history, with reports of mental health issues affecting his grandfather and one of his brothers, who were said to have been admitted to psychiatric institutions. While it is impossible to draw direct conclusions, such family histories can sometimes cast a long and complex influence.

The Philippine Enigma: Final Years and Disappearance

The outbreak of World War II dramatically reshaped the global landscape and had a profound impact on Locatelli's life. Seeking refuge from the escalating conflict in Europe and Asia, he and his wife Erminia moved to Manila in the Philippines. The Philippines, then a U.S. territory, might have seemed a safer haven. He continued to paint, capturing the local scenes and people, adding another layer to his diverse oeuvre.

However, this period was to be his last. On February 24, 1943, during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines, Romualdo Locatelli went on a hunting trip in the Rizal area, a region east of Manila known for its rugged terrain. He never returned. The circumstances of his disappearance remain shrouded in mystery. Was he a casualty of war, a victim of guerrilla activity, an accident in the wilderness, or did he perhaps choose to disappear? No definitive evidence has ever surfaced.

His wife, Erminia, was left to grapple with the devastating loss and uncertainty. After the war, she eventually relocated to San Francisco in the United States, where she reportedly worked in education, carrying the memory of her husband and his unresolved fate. The Locatelli family in Italy, particularly his mother and siblings, were deeply affected by his disappearance, which remained an open wound and a subject of enduring speculation. For them, the loss of Romualdo was not just the loss of a talented artist but of a beloved son and brother whose end was never truly known.

Legacy and Rediscovery

Despite his relatively short life and the abrupt end to his career, Romualdo Locatelli left behind a significant body of work. His paintings, particularly those from his time in Southeast Asia, are highly prized by collectors and institutions. In the post-war era, appreciation for his art grew, and his works began to command significant prices at auction, a testament to their enduring quality and the allure of his story.

Locatelli's art bridges several important currents of the early 20th century. He combined a solid academic grounding with a modernist sensibility, and his engagement with "Orientalist" themes was nuanced by a genuine fascination with the cultures he encountered. He can be seen in the context of other European artists who traveled East, such as the aforementioned Walter Spies and Rudolf Bonnet in Bali, or the Belgian painter Adrien-Jean Le Mayeur de Merprès, whose vibrant depictions of Balinese life share some thematic similarities. Indonesian artists like Lee Man Fong, who also blended Eastern and Western techniques, later built upon the cross-cultural artistic dialogues that figures like Locatelli participated in.

The mystery surrounding his disappearance has undoubtedly added to his legend, casting him as a romantic, almost mythical figure. His story is a poignant reminder of how individual lives, especially those of artists who often operate on the peripheries of conventional society, can be dramatically impacted by larger historical forces like war and colonial upheaval.

Locatelli in the Context of His Contemporaries

Placing Romualdo Locatelli within the broader art historical context of his time reveals an artist who, while perhaps not a radical avant-gardist in the vein of the Surrealists or Cubists, was nonetheless a distinctly modern painter. His work in Italy coincided with the rise of movements like Novecento Italiano, which sought a return to order and classical forms, yet also with lingering Futurist energies and individual modernists like Giorgio Morandi, who pursued a quiet, introspective modernism. Locatelli carved his own path, blending figurative tradition with a fresh, expressive style.

His portraiture can be compared to other society painters of the era, but his approach often had a raw energy that distinguished it. While not as overtly stylized as Modigliani or as flamboyantly elegant as Boldini (who was of an earlier generation but whose influence lingered), Locatelli's portraits possessed a psychological acuity and a vigorous application of paint.

In Southeast Asia, his work contributed to the rich tapestry of art produced by Westerners in the region. Unlike some Orientalist painters of the 19th century, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme or Rudolf Ernst, whose depictions could sometimes tend towards the stereotypical or overly romanticized, Locatelli's paintings, particularly of Balinese subjects, often convey a sense of direct observation and engagement. His focus on capturing the individual character of his sitters and the specific atmosphere of a place aligns him more with the observational modernism that was developing globally.

Conclusion: An Enduring Fascination

Romualdo Locatelli's life was a compelling journey of artistic exploration that spanned continents and cultures. From his early training in Bergamo to his celebrated works in Italy and his profound engagement with the East, he consistently produced art that was vibrant, insightful, and technically accomplished. His modernist leanings, combined with a deep appreciation for the human subject and the natural world, resulted in a body of work that continues to captivate.

The unresolved mystery of his disappearance in the Philippines in 1943 adds a layer of poignant intrigue to his story, transforming him into a figure of enduring fascination. While his career was tragically cut short, the paintings he left behind serve as a powerful testament to his unique talent and his adventurous spirit. Romualdo Locatelli remains an important, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the diverse landscape of 20th-century art, a painter whose journey from West to East enriched his vision and left an indelible mark. His legacy is not just in the canvases that survive, but in the story of a life lived with artistic passion, cut short by the tumult of history, yet resonating still.