Samuel Hieronymus Grimm (1733-1794) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the annals of 18th-century European art. A Swiss-born artist who spent the most productive part of his career in England, Grimm was a master of topographical watercolour and pen-and-ink drawing. His prolific output offers an invaluable visual record of the landscapes, architecture, social customs, and historical events of his time, rendered with a distinctive blend of precision and subtle charm. His work bridges the gap between purely documentary illustration and the burgeoning Romantic appreciation of landscape, securing his place as a key practitioner of topographical art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Switzerland

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm was born on January 18, 1733, in Burgdorf, a town near Bern in Switzerland. His early inclinations were not solely artistic; he also harboured literary ambitions. This creative duality manifested in 1758 with the publication of a two-volume collection of his poems. However, the visual arts soon became his primary focus. Around 1760, Grimm moved to Bern, the cantonal capital, to pursue formal artistic training.

His first significant mentor was Johann Ludwig Aberli (1723-1786), a prominent Bernese topographical artist. Aberli was renowned for his picturesque views of Swiss scenery, particularly the Alps, and for popularising a specific technique of coloured outline etching. Interestingly, Aberli himself had been a student of Grimm's own grandfather, Johann Rudolf Grimm, a painter of some local repute. Under Aberli, Samuel Hieronymus would have honed his skills in precise draughtsmanship and the application of watercolour washes, techniques fundamental to topographical art. This period laid the groundwork for his meticulous attention to detail and his ability to capture the specific character of a place.

Parisian Sojourn and Further Development

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Grimm relocated to Paris in 1765. The French capital was a vibrant artistic centre, offering exposure to a wider range of styles and influences. In Paris, he studied under Johann Georg Wille (1715-1808), a German engraver and art dealer who had established a highly successful studio. Wille was a pivotal figure in the Parisian art scene, known for his fine engravings after Dutch and Flemish masters, as well as contemporary French painters.

Wille's studio attracted many aspiring artists from across Europe, and Grimm's time there would have further refined his technical skills, particularly in landscape and topographical depiction. He would have been exposed to the French rococo sensibility, though his own style retained a more Northern European sobriety and focus on factual representation. This period in Paris, though relatively brief, was crucial in equipping him with the polish and confidence to establish himself as an independent artist.

Relocation to London and a Flourishing Career

In 1768, Samuel Hieronymus Grimm made the most decisive move of his career: he relocated to London. England, at this time, was experiencing a surge in interest in its own history, antiquities, and natural scenery. This cultural climate provided fertile ground for an artist with Grimm's particular talents. He would spend the remainder of his life in London, becoming a familiar figure in its artistic circles.

Grimm quickly established himself as a skilled and reliable topographical artist. He became a regular exhibitor at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts, which had been founded in the very year of his arrival in London under the presidency of Sir Joshua Reynolds. Exhibiting alongside prominent British artists such as Thomas Gainsborough, Richard Wilson, and Paul Sandby, Grimm showcased his detailed watercolours and drawings to a discerning public. His works were appreciated for their accuracy and the quiet charm with which he imbued his subjects.

Patronage and Prolific Output

A significant factor in Grimm's success in England was the patronage he received. His most important and enduring patron was the Reverend Sir Richard Kaye, 6th Baronet, Dean of Lincoln and a keen antiquarian. Their association began in the mid-1770s and lasted for nearly two decades, providing Grimm with consistent employment and financial stability. For Kaye, Grimm undertook extensive sketching tours, meticulously documenting landscapes, country houses, churches, and ancient monuments across various English counties, including Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire, and Lincolnshire.

This patronage enabled Grimm to be exceptionally prolific. It is estimated that he produced over 2,600 watercolours and drawings for Sir Richard Kaye alone. These works form a remarkable archive of late 18th-century Britain, capturing not only the grand estates but also more humble rural scenes and aspects of daily life. His diligence and the sheer volume of his output are testaments to his work ethic and the demand for his skills. Other notable patrons and collectors of his work included the antiquarian Sir William Burrell, for whom he documented Sussex, the naturalist Gilbert White, and the writer and traveller Henry Penruddocke Wyndham.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Grimm's artistic style is characterized by its meticulous precision and clarity. He primarily worked in watercolour, often combined with pen and ink outlines. His technique is often described as "tinted" or "stained" drawing, a common method in 18th-century watercolour practice. This typically involved a careful pencil underdrawing, followed by the application of light, transparent washes of grey or neutral tints to establish shadows and form. Finally, "local colour" – the actual colours of the objects – would be applied, often subtly. The pen and ink outlines served to define forms crisply and add detail.

This method, while capable of producing aesthetically pleasing results, was also highly practical. It allowed for the accurate recording of information, making his works valuable as documents. The clarity of line and controlled application of colour also made his drawings well-suited for translation into engravings, a common way for topographical views to be disseminated to a wider audience. While his contemporary Paul Sandby, often called the "father of English watercolour," was exploring more atmospheric and painterly effects, Grimm generally adhered to a more descriptive and linear approach, though his best works possess a delicate beauty and a keen sense of place.

His compositions are typically well-balanced and straightforward, designed to present the subject clearly. Figures are often included, not merely as staffage, but to animate the scene and provide a sense of scale and context, often depicting local inhabitants engaged in everyday activities. This adds a layer of social observation to his topographical work.

Thematic Concerns: Landscapes, Antiquities, and Social Life

Grimm's thematic range was broad, though always rooted in careful observation. His primary focus was on the British landscape, encompassing both natural scenery and the built environment. He travelled extensively, recording panoramic views, specific country estates, village scenes, and individual buildings of interest. His depictions of cathedrals, parish churches, castles, and ruins were particularly sought after by antiquarians.

His work for Gilbert White, providing illustrations for "The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne" (published 1789), showcases his ability to capture the specific character of a locale and its natural history. These illustrations are notable for their sensitivity and accuracy, perfectly complementing White's text. Grimm's drawings for this seminal work include views of Selborne village, its church, and surrounding landscapes, as well as details of flora and fauna.

Beyond straightforward topography, Grimm also documented historical events and contemporary social life. He produced detailed reconstructions of historical scenes, such as "The Coronation Procession of Edward VI," which, though imagined, would have been based on careful research of historical accounts and visual precedents. He also recorded contemporary events, like the rebuilding of Calcot Manor Church, providing a visual chronicle of change.

Satirical Works and Social Commentary

An interesting, and perhaps less widely known, facet of Grimm's oeuvre is his work as a caricaturist and social satirist. Living in London, a hub for satirical printmaking with artists like Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray pushing the boundaries of the genre, Grimm also turned his hand to humorous and critical depictions of contemporary society.

He produced a number of drawings and prints that poked fun at social fashions, political figures, and the follies of the age. These works, often published by figures like Carington Bowles of St. Paul's Churchyard, demonstrate a sharp wit and a keen eye for human absurdity. While his satirical output may not have reached the biting intensity of Gillray or the boisterous energy of Rowlandson, it reveals another dimension to his artistic personality, showing him to be an engaged observer of the social and political currents of his time. These works often employed a more fluid and expressive line than his topographical drawings, adapting his style to the demands of caricature.

Representative Works

Given Grimm's prolific output, singling out a few representative works is challenging, but several categories and specific examples highlight his contributions:

Illustrations for Gilbert White's "The Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne": These are among his most famous works, including "View of Selborne from the Hanger" and "The Plestor." They are celebrated for their faithful depiction of the Hampshire village and its surroundings.

Topographical Views for Sir Richard Kaye: The vast collection of drawings made for Kaye, now largely in the British Library, includes numerous views of churches, country houses, and landscapes across England. Examples include detailed renderings of Lincoln Cathedral, views in Derbyshire such as scenes around Chatsworth or Haddon Hall, and various Nottinghamshire estates.

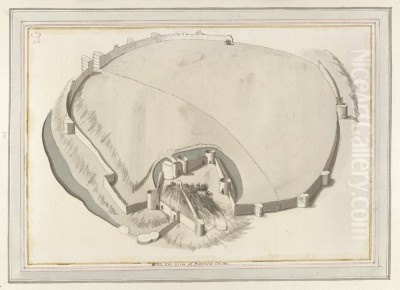

Antiquarian Drawings: His depictions of ancient monuments, ruins like Fountains Abbey or Rievaulx Abbey, and archaeological sites were highly valued. These often included precise measurements and details important for antiquarian study.

Historical Reconstructions: "The Coronation Procession of Edward VI" (British Museum) is a notable example of his work in this genre, showcasing his ability to marshal complex compositions and historical detail.

Social Scenes and Caricatures: Works like "A Macaroni Dressing Room" or various street scenes capture the flavour of 18th-century London life and its fashionable excesses.

"The Rebuilding of Calcot Manor Church, Gloucestershire": This series of drawings meticulously documents the architectural transformation, highlighting his role as a recorder of contemporary change.

His body of work, taken as a whole, provides an unparalleled visual encyclopedia of late Georgian Britain.

Grimm and His Contemporaries

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm operated within a vibrant British art scene. As mentioned, he exhibited at the Royal Academy alongside its leading lights. While his topographical focus differed from the grand manner portraiture of Sir Joshua Reynolds or the society portraits and rustic landscapes of Thomas Gainsborough, he shared the era's growing interest in the national landscape.

His closest artistic kinship was with other topographical artists. Paul Sandby (1731-1809) was a pre-eminent figure in this field, also a founding member of the Royal Academy. Sandby's work, particularly his watercolours of Windsor Castle and Scottish scenery, often displayed a greater atmospheric richness and a more painterly approach than Grimm's, but both shared a commitment to accurate depiction. Grimm's works have, at times, been misattributed to Sandby, indicating a similarity in subject matter and general approach.

Other notable topographical artists of the period included Michael "Angelo" Rooker (1746-1801), known for his picturesque views and architectural subjects, often engraved for publications. Thomas Hearne (1744-1817), who collaborated with the engraver William Byrne on "The Antiquities of Great Britain," produced highly finished watercolours of historical sites, similar in spirit to Grimm's antiquarian work. Edward Dayes (c.1763-1804), though of a slightly later generation, continued the tradition of detailed topographical watercolour, and was also a teacher to the young J.M.W. Turner.

In the realm of caricature, Grimm's contemporaries were formidable. Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827) was a master of exuberant and often bawdy social satire, his style far more flamboyant than Grimm's. James Gillray (1756-1815) was the leading political satirist, his prints known for their savage wit and complex allegories. While Grimm's satirical works were generally gentler, they partook of the same critical spirit that animated these more famous caricaturists. One might also consider the work of Henry William Bunbury (1750-1811), an amateur caricaturist whose humorous social scenes were immensely popular.

Grimm's connection with the naturalist Gilbert White also places him in the context of artists who contributed to scientific and natural historical publications, a field that was expanding rapidly. Artists like Sydney Parkinson (c.1745-1771), who sailed with Captain Cook, and George Stubbs (1724-1806), renowned for his anatomical studies of animals, particularly horses, represent the intersection of art and scientific inquiry, a domain to which Grimm's Selborne illustrations belong.

The engraver Johann Georg Wille, Grimm's teacher in Paris, also connects him to a broader European network. Wille's studio was a meeting point for artists like Jean-Georges Wille (his son, also an engraver) and numerous German and Scandinavian artists who passed through Paris.

Legacy and Influence

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm's primary legacy lies in the vast and detailed visual archive he created. In an era before photography, his drawings served as crucial records of buildings (many since altered or demolished), landscapes, and social customs. His work was, and continues to be, invaluable to historians, antiquarians, and architectural historians.

His influence on subsequent artists is perhaps more subtle than that of more stylistically innovative figures. However, his commitment to accuracy and his refined watercolour technique contributed to the development of the British school of watercolour painting. Artists like David Cox (1783-1859) and Peter De Wint (1784-1849), while developing their own distinct styles, built upon the foundations laid by earlier topographical artists like Grimm. Even the great J.M.W. Turner (1775-1851) began his career producing topographical watercolours, and would have been aware of the work of established practitioners like Grimm. Turner's early meticulousness, before his evolution into a more Romantic and abstract style, shows an understanding of the topographical tradition.

Grimm's work exemplified the Enlightenment's drive to catalogue and understand the world. His methodical approach and dedication to factual representation were perfectly suited to the antiquarian and scientific interests of his patrons. He helped to elevate topographical art beyond mere map-making, imbuing it with a quiet aesthetic appeal and a sense of historical consciousness.

Rediscovery and Collections

Despite his success during his lifetime, Grimm's reputation somewhat faded in the 19th century as artistic tastes shifted towards more Romantic and expressive styles. However, the 20th and 21st centuries have seen a renewed appreciation for his work, recognizing its historical importance and artistic merit. A landmark event in this reassessment was the comprehensive exhibition of his work held at the Kunstmuseum Bern in 2014, which helped to re-establish his significant position in the history of both Swiss and British art.

Grimm died in London on April 14, 1794, in his lodgings on Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. He bequeathed his property, including a substantial collection of his own drawings, to a niece in Switzerland. Today, his works are held in major public collections, most notably the British Library (which houses the extensive Kaye Collection), the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Tate Britain, the Yale Center for British Art, and various county record offices and regional museums throughout the UK. These collections ensure that his meticulous vision of 18th-century Britain remains accessible for study and appreciation.

Conclusion

Samuel Hieronymus Grimm was more than just a skilled draughtsman; he was a dedicated chronicler of his adopted country. His thousands of drawings and watercolours provide an irreplaceable window into the landscapes, architecture, and social fabric of 18th-century England. While he may not have possessed the revolutionary genius of some of his contemporaries, his precision, diligence, and the sheer scope of his output have secured him a lasting place in art history. His work serves as a testament to the value of careful observation and the power of art to preserve the past, offering insights that continue to enrich our understanding of a pivotal period in British history and culture. His ability to blend factual recording with a subtle artistic sensibility makes him a fascinating and important figure, whose contributions are increasingly recognized and celebrated.