Scipione Pulzone, often known as Il Gaetano after his birthplace, stands as a pivotal figure in Italian art during the latter half of the 16th century. Active primarily in Rome, he earned renown as one of the era's most sought-after portraitists, capturing the likenesses of popes, cardinals, and nobles with remarkable skill and psychological depth. His work bridges the High Renaissance ideals exemplified by artists like Raphael with the burgeoning demands for clarity and realism spurred by the Counter-Reformation.

Regarding his lifespan, historical sources present some discrepancies, particularly concerning his birth year. While some accounts suggest 1540 or even 1550, the most corroborated evidence points to his birth in 1544 in Gaeta, a coastal town near Naples. His death is more consistently documented as occurring in Rome in 1598. This places his flourishing firmly within a period of significant religious and artistic transformation in Italy.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born Scipione Pulzone in Gaeta around 1544, his early life and training remain somewhat sparsely documented. It is clear, however, that he relocated to Rome, the vibrant center of artistic patronage and innovation, to pursue his career. While his specific teachers are not definitively named in all sources, his style reveals a profound engagement with the legacy of High Renaissance masters, particularly Raphael, whose grace and compositional harmony echo in Pulzone's works.

Furthermore, his meticulous attention to detail and texture suggests an awareness and absorption of Northern European painting techniques, possibly gleaned from Flemish artists active in Italy or through circulated prints. Artists like Antonis Mor, renowned for his court portraits across Europe, set precedents for the kind of detailed realism that Pulzone would adapt to the Roman context. His formation likely involved studying both classical sculpture and the works of contemporary Roman painters, perhaps including figures like Jacopo del Conte or Girolamo Siciolante da Sermoneta, though direct tutelage is speculative.

Rome: The Crucible of the Counter-Reformation

Pulzone arrived and worked in Rome during a period of intense religious fervor and institutional reform within the Catholic Church, known as the Counter-Reformation. This movement, formalized partly through the Council of Trent, had profound implications for the arts. There was a renewed emphasis on clarity, decorum, piety, and emotional directness in religious imagery, moving away from some of the complexities and perceived ambiguities of Mannerism.

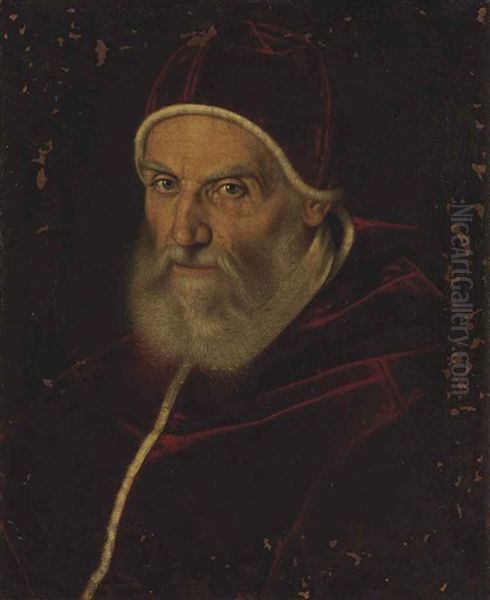

Art became a crucial tool for reinforcing Catholic doctrine and authority. Portraiture, too, took on heightened significance, serving not just to record likeness but also to convey the sitter's status, piety, and role within the Church hierarchy. Pulzone thrived in this environment, perfectly positioned to meet the demands of powerful patrons seeking images that were both realistic and imbued with a sense of dignity and spiritual gravity. His contemporaries included artists navigating similar demands, such as Federico Zuccari and Girolamo Muziano, while the towering influence of Michelangelo's late works still resonated. The city was a melting pot where artists like El Greco would briefly work before finding fame elsewhere, and where the revolutionary naturalism of Caravaggio would soon emerge.

The Apex of Portraiture

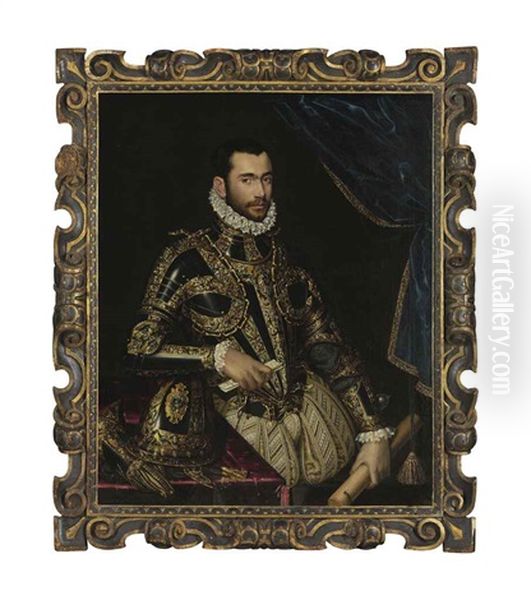

Scipione Pulzone's reputation rests significantly on his extraordinary talent for portraiture. He became the favored painter of the Roman elite, including high-ranking clergy and aristocracy. His style was characterized by an almost photographic realism, capturing not only the precise physical features of his sitters but also conveying a sense of their inner life and personality. This psychological depth, combined with an exquisite rendering of fabrics, jewels, and textures, made his portraits highly valued.

His approach synthesized various influences. The formal structure often recalls the courtly portrait traditions, while the intense focus on detail owes much to Flemish painting. Yet, Pulzone infused this with a distinctly Italian sensibility, particularly a softness in modeling and sometimes a richness of color reminiscent of Venetian masters like Titian, whose influence permeated Italian art. He balanced meticulous naturalism with a degree of idealization appropriate for his high-status subjects.

Key patrons included prominent figures of the Church and state. He painted multiple cardinals, demonstrating his esteemed position. Among his most celebrated works are the Portrait of Cardinal Granvelle (Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle), noted for its penetrating gaze and detailed rendering of the cardinal's attire, now housed in the Harvard Art Museums. Another significant work is the Portrait of Cardinal Ferdinando de' Medici, also at Harvard, showcasing his skill in capturing the shrewd intelligence of the future Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Other important portraits include those of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese (an early work, Rome National Gallery), Cardinal Giovanni Battista Ricci (linked to Counter-Reformation theological discussions), and Cardinal Giaccomo Savelli. He also painted members of powerful families, such as Jacopo Boncompagni (nephew of Pope Gregory XIII) and Francesco de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, further cementing his connection to the highest echelons of Italian society. These portraits served as powerful statements of identity and authority in a hierarchical society.

Religious Commissions and Devotional Art

While best known for portraits, Pulzone was also a significant painter of religious subjects. His approach to sacred themes aligned closely with the directives of the Counter-Reformation, emphasizing clarity, emotional sincerity, and adherence to scripture. His religious works often display a more overt classicism, drawing inspiration from Raphael and ancient sculpture, aiming for a style described as "senza tempo" – timeless and enduring.

A notable example is The Lamentation, housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This work showcases his ability to handle complex multi-figure compositions with emotional restraint and devotional intensity. The figures are rendered with anatomical accuracy and expressive, though dignified, grief. The composition is balanced, the colors are rich yet somber, and the overall effect is one of profound piety suitable for contemplation.

Another significant religious work is the Assumption of the Virgin, now in the Wellington Museum, London. This painting demonstrates his ability to blend different stylistic currents, incorporating Venetian color and light effects alongside Flemish-inspired detail within a grand, devotional composition. These works were often commissioned for churches and private chapels, intended to inspire faith and devotion in the viewer, fulfilling the didactic role assigned to art by the reformed Church. His contemporaries in religious painting included artists like Federico Barocci, known for his emotive and color-rich altarpieces.

Style, Technique, and Influences

Pulzone's artistic signature lies in his unique synthesis of diverse stylistic threads. His grounding in the Roman tradition provided a foundation in classical composition and the idealized forms inherited from Raphael. However, he tempered this with an intense naturalism and a meticulous rendering of surfaces that points strongly towards Northern European, particularly Flemish, influence. This combination allowed him to create portraits that were both dignified representations of status and startlingly lifelike depictions of individuals.

His technique involved careful underdrawing and layered application of paint to achieve smooth finishes and subtle gradations of tone, especially evident in the rendering of skin and luxurious fabrics like silk and velvet. The precision could be almost microscopic, yet it rarely devolved into mere surface decoration; it always served the larger purpose of creating a convincing and compelling image of the sitter. The influence of Venetian art, perhaps absorbed through visits or the study of works in Roman collections, is seen in his sophisticated use of color and light to model form and create atmosphere, particularly in his religious paintings.

He navigated the artistic currents of his time, absorbing lessons from predecessors like Raphael and Titian, engaging with the international trends represented by Flemish portraiture (perhaps Antonis Mor), and working alongside Roman contemporaries like Muziano and Zuccari. While distinct from the intense Mannerism of some artists active earlier in the century, his work predates and perhaps even subtly informs the more dramatic naturalism that would characterize the work of Caravaggio and the Baroque innovations of the Carracci brothers (Annibale and Agostino) who rose to prominence around the time of Pulzone's death.

Connections with Contemporaries

Direct evidence of personal interactions between Pulzone and other major figures like El Greco or Caravaggio is scarce, based on the available historical records. However, their careers did overlap in Rome, suggesting awareness, if not direct collaboration or correspondence.

El Greco was active in Rome between 1570 and 1576, striving to establish himself, particularly as a portraitist. It is documented that one of El Greco's portraits, likely the Vincenzo Anastagi, was exhibited alongside Pulzone's Portrait of Jacopo Boncompagni. This indicates they moved within the same artistic circles and competed for similar patronage, at least for a time. Both artists shared an interest in combining naturalistic detail with expressive intensity, albeit developing in vastly different stylistic directions later in their careers. No records of direct communication or joint projects between Pulzone and El Greco have surfaced.

Regarding Caravaggio, who arrived in Rome in the early 1590s, there is also no documented personal connection with Pulzone, who died in 1598. However, art historians have noted potential stylistic links. Pulzone's commitment to naturalism and detailed observation, particularly evident in his portraits and works like The Lamentation, has been suggested as part of the artistic environment that may have contributed to the development of Caravaggio's more radical realism. Both artists engaged deeply with religious themes, though Caravaggio's approach would ultimately be far more dramatic and confrontational. Again, no evidence supports direct communication or collaboration. Pulzone's network certainly included interactions with patrons shared by other artists, and likely professional acquaintance with numerous painters active in Rome, possibly including female artists gaining prominence like Lavinia Fontana or recalling the earlier success of Sofonisba Anguissola. He is known to have collaborated with Jacopo Zucchi on decorations for the Medici.

Patronage, Workshop, and Unresolved Questions

Pulzone's success was heavily reliant on a robust network of patrons. His ability to secure commissions from Popes, numerous influential cardinals (Granvelle, Ricci, Farnese, Savelli, Ferdinando de' Medici), and powerful families like the Medici and Boncompagni speaks volumes about his reputation and diplomatic skill. These patrons not only provided financial support but also enhanced his prestige, leading to further commissions. His involvement with the Medici extended to projects beyond portraiture, such as contributing to the decoration of one of their villas.

Despite his fame, certain aspects of his working practice remain unclear. The consistency and high finish of his output raise questions about the extent to which he utilized workshop assistants. While common practice for successful artists of the period, definitive technical studies confirming the hands of assistants in specific works attributed to Pulzone are often lacking or inconclusive. The motivation behind creating multiple versions or copies of certain successful portraits, and the methods by which these were produced and disseminated, are also areas requiring further research. These unanswered questions highlight the complexities of artistic production and the art market in late 16th-century Rome.

Critical Reception and Lasting Legacy

Scipione Pulzone was highly esteemed during his lifetime, particularly for his portraiture. His ability to capture a truthful likeness while maintaining decorum made him exceptionally suited to the demands of Counter-Reformation Rome. His meticulous technique and psychological acuity were widely admired. His portraits were seen as benchmarks of realism combined with aristocratic elegance.

However, his work was not without criticism. His very commitment to naturalism occasionally clashed with prevailing expectations for religious art. An altarpiece, reportedly depicting angels ("Angels' Wings"), was allegedly rejected by the Church of the Gesù in Rome for being too lifelike, deemed lacking in the appropriate divine idealization. Furthermore, while his religious paintings were respected for their piety and technical skill, some later critics might view them as somewhat conservative, adhering closely to established compositional formulas derived from masters like Raphael, rather than forging radically new paths in the manner of Caravaggio or the Carracci shortly after him.

Despite these debates, Pulzone's position in art history is secure. He represents a crucial moment of synthesis, blending High Renaissance grace with a new emphasis on detailed realism and psychological presence, influenced by both Northern European trends and the specific cultural climate of Counter-Reformation Rome. His portraits remain compelling documents of the personalities and power structures of his era. His meticulous style and commitment to observation provided an important precedent, contributing to the broader currents of naturalism that would flow into the Baroque period. Scipione Pulzone (1544-1598) remains a defining painter of the late 16th century, a master whose brush captured the faces of an age of profound change.