Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century Polish art, a painter whose canvases captured the spirit of his time through meticulous realism, a profound understanding of his subjects, and a particular flair for portraiture and equestrian scenes. Born in an era of political turmoil and national aspiration for Poland, his work often reflected both the grandeur of aristocratic life and the valor of military tradition, alongside an intriguing fascination with the Orient. His career, spanning several decades and artistic centers, cemented his reputation as a skilled academic painter, admired for his technical prowess and his ability to imbue his subjects with dignity and life.

Early Life and Formative Artistic Education

Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz was born in 1852, with sources variously citing Wieliczka or the nearby Vitkowice as his birthplace, both in the vicinity of Krakow. This region, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire following the partitions of Poland, was a crucible of Polish culture and identity. His artistic inclinations emerged early, leading him to enroll in the Kraków School of Fine Arts (Szkoła Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie). Here, he studied under Władysław Łuszczkiewicz, a prominent painter and educator himself, known for his historical paintings and portraits, who would have instilled in Ajdukiewicz a strong foundation in academic drawing and composition. The Krakow school at this time was a vital center for nurturing Polish artistic talent, with figures like the monumental historical painter Jan Matejko casting a long shadow, emphasizing patriotic themes and meticulous historical reconstruction.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Ajdukiewicz, like many aspiring artists of his generation, traveled abroad for further study. He attended the prestigious art academies in Vienna and Munich. The Academy of Fine Arts Vienna was a bastion of historicism and academic tradition, where artists like Hans Makart were creating opulent, large-scale compositions. Munich, on the other hand, was renowned for its "Munich School" of realism, which particularly attracted Polish artists. Figures like Józef Brandt, who became famous for his dramatic battle scenes and depictions of Polish and Cossack life, and Alfred Wierusz-Kowalski, known for his snowy landscapes with wolves and hunting scenes, were active there. These environments would have exposed Ajdukiewicz to a high level of technical skill, a focus on realistic depiction, and a variety of popular themes, from grand historical narratives to intimate genre scenes. His cousin, Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz, older by nine years and also a painter with a similar thematic interest, particularly in portraits and genre scenes, likely shared some of these formative experiences.

The Allure of the Orient and Expanding Horizons

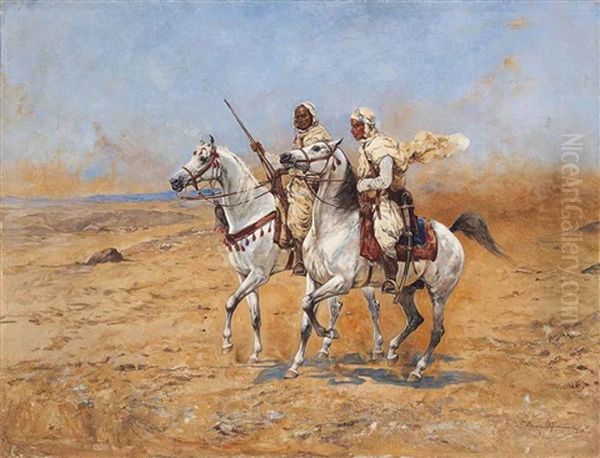

A pivotal moment in Ajdukiewicz's artistic development was his journey in 1877. Accompanied by Count Władysław Branicki, a member of a prominent Polish aristocratic family and likely a patron, Ajdukiewicz embarked on an extensive tour that took him through Syria, Egypt, Turkey, and the Crimea. This immersion in the cultures, landscapes, and daily life of the Near East had a profound impact on his thematic repertoire and visual palette. The 19th century saw a widespread European fascination with the "Orient," and artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme in France and Gustav Bauernfeind in Germany were captivating audiences with their detailed and often romanticized depictions of these lands.

Ajdukiewicz's Orientalist works, such as "At the Well" (1888), demonstrate his keen observation and ability to capture the exotic atmosphere, the quality of light, and the distinct characteristics of the people and their attire. These paintings were not merely picturesque souvenirs but often carefully composed scenes that showcased his skill in rendering textures, from flowing robes to the rough hides of camels, and his interest in human interaction within these settings. His travels provided him with a rich source of inspiration that he would draw upon throughout his career, adding a distinct dimension to his oeuvre beyond the more conventional European subjects.

Vienna: A Hub of Artistic Activity

In 1882, Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz made a significant career move by settling in Vienna, the vibrant capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. This city was a major European cultural center, boasting a sophisticated clientele and a thriving art market. It was here that Ajdukiewicz truly established his reputation. A notable event was his taking over the studio of Hans Makart, a towering figure in Viennese art circles known for his lavish historical and allegorical paintings, whose death in 1884 left a void. This move symbolized Ajdukiewicz's ambition and his growing stature.

In Vienna, Ajdukiewicz quickly gained favor among art enthusiasts and patrons, particularly for his portraits and equestrian scenes. He became known as a court painter, receiving commissions from aristocratic families and even royalty. His ability to capture not only a likeness but also the status and character of his sitters was highly valued. His works were regularly exhibited, and he achieved international recognition, notably winning a gold medal at the Vienna International Art Exhibition in 1891 and receiving accolades at exhibitions in Munich. This period marked the peak of his professional success, solidifying his position as a respected academic painter. Other Polish artists also found success in Vienna, contributing to the rich cultural tapestry of the empire, though Ajdukiewicz carved a distinct niche with his particular blend of portraiture and military-equestrian themes.

Master of Portraiture and Equestrian Art

Portraiture was a cornerstone of Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz's artistic output. He possessed a remarkable ability to convey the personality and social standing of his subjects, often depicting them in formal attire or within settings that underscored their status. His portraits are characterized by their refined technique, careful attention to detail in clothing and accessories, and a dignified, often psychologically astute, rendering of the sitter. He painted numerous members of the European aristocracy, military officers, and prominent public figures.

His equestrian portraits were particularly celebrated. The depiction of horse and rider has a long and noble tradition in European art, and in Poland, with its strong cavalry traditions and aristocratic culture, it held special significance. Artists like Juliusz Kossak and his son Wojciech Kossak, as well as the earlier Romantic painter Piotr Michałowski, had established a powerful legacy in this genre. Ajdukiewicz continued this tradition with great skill. His painting "Leopold von Croy in Campaign" (also known as "Portrait of General Leopold von Croy at a Parade," 1888) is a prime example. It showcases his mastery in rendering the powerful anatomy of the horse, the intricate details of the military uniform, and the commanding presence of the general. Such works were not just likenesses but also statements of power, prestige, and martial prowess. His ability to capture the dynamic energy of the horse and the confident bearing of the rider made these works highly sought after.

Battle Scenes and Historical Narratives

Beyond individual and equestrian portraits, Ajdukiewicz also ventured into battle scenes and historical paintings, genres that allowed him to combine his skill in depicting horses and human figures in dynamic action. These compositions often drew on Polish military history or contemporary military events, resonating with a sense of national pride and historical consciousness. While perhaps not on the epic scale of Jan Matejko's grand historical canvases, Ajdukiewicz's battle scenes were noted for their realism, energy, and attention to historical accuracy in uniforms and equipment.

His paintings like "Crossing the Desert" or "Rider: Horse and Rider" (though the latter might be more of a genre or equestrian study) hint at his capacity for narrative and his interest in placing figures within broader, often dramatic, landscapes. The influence of the Munich School, with its emphasis on realistic historical and genre painting, is evident in these works. Artists like Józef Brandt, with his vivid depictions of 17th-century Polish-Cossack conflicts, set a high bar for this genre, and Ajdukiewicz contributed his own distinct vision, often characterized by a slightly more polished, academic finish.

Artistic Style and Technique

Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz was fundamentally a realist painter, working within the academic tradition prevalent in the latter half of the 19th century. His style was characterized by meticulous draftsmanship, a smooth, polished finish, and a careful rendering of light and shadow to create a convincing sense of volume and space. He paid great attention to detail, whether it was the texture of fabric, the gleam of metal, or the musculature of a horse. His color palette was generally rich and naturalistic, though his Orientalist scenes sometimes allowed for more vibrant and exotic hues.

His compositions were carefully constructed, often adhering to established academic principles of balance and clarity. While he was a contemporary of emerging modernist movements like Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, and later Symbolism as seen in the "Young Poland" (Młoda Polska) movement with artists like Jacek Malczewski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and Józef Mehoffer, Ajdukiewicz remained largely committed to the realist-academic approach. His work did not engage with the avant-garde's formal experimentation or subjective distortions but instead focused on achieving a high degree of verisimilitude and conveying the dignity and character of his subjects through established pictorial means. This adherence to tradition ensured his popularity with a more conservative clientele but also meant his work might have been seen as less innovative by proponents of modernism.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Ajdukiewicz operated within a vibrant European art world. In Poland, historical painting, as championed by Matejko, was dominant, but genre painting and portraiture also flourished. Artists like Aleksander Gierymski and Maksymilian Gierymski were exploring different facets of realism, often with a focus on Polish life and landscape. In Munich, the Polish colony of artists was significant, with figures like Władysław Czachórski excelling in highly finished genre scenes and portraits.

His time in Vienna placed him in a cosmopolitan environment. While Hans Makart's opulent style was influential, Vienna also had a strong tradition of Biedermeier realism and later saw the rise of the Vienna Secession with artists like Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, who broke dramatically with academic conventions. Ajdukiewicz, however, maintained his established style, catering to a clientele that appreciated traditional craftsmanship and representational accuracy. His relationship with his cousin, Zygmunt Ajdukiewicz, who also worked in Vienna and shared similar artistic interests, would have provided a familial and professional connection. He also reportedly collaborated on a film project, "Nie ma Polski bez Sahary" (There is no Poland without the Sahara), with director Michał Waszyński and fellow artists Stanisław Chełbowski and Jan Ciągiński, indicating an openness to new media, though this aspect of his career is less documented.

Later Years, Legacy, and Death

Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz continued to paint actively into the early 20th century. He remained a respected figure, though the artistic landscape was rapidly changing with the rise of modernism. His work, deeply rooted in 19th-century academic realism, represented a tradition that was being challenged by new artistic philosophies and styles.

He passed away on January 9, 1916, in Krakow. His death occurred during the tumultuous years of World War I, a conflict that would ultimately lead to Poland regaining its independence in 1918. His life and career thus spanned a critical period in Polish history, from the aftermath of failed uprisings and ongoing foreign rule to the brink of national rebirth.

Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz's legacy lies in his contribution to Polish and European academic painting. He was a master of his craft, particularly renowned for his elegant portraits, dynamic equestrian scenes, and evocative Orientalist works. His paintings are held in numerous museums and private collections, valued for their technical excellence, historical interest, and their reflection of the tastes and values of his era. While not an avant-garde innovator, he was a highly accomplished artist who excelled within his chosen tradition, leaving behind a body of work that continues to be appreciated for its artistry and its depiction of a bygone world. He remains an important representative of Polish realism and academic art, a testament to the enduring power of skilled representation and insightful portraiture. His distinction from the similarly named but unrelated Kazimierz Ajdukiewicz, a prominent logician and philosopher of the Lvov-Warsaw school, is important for art historical clarity. Tadeusz Ajdukiewicz's contribution was firmly in the visual arts, where he carved a distinguished career.