Théophile Emile Achille de Bock stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure within the rich tapestry of nineteenth-century Dutch art. Born in The Hague on January 14, 1851, and passing away in Haarlem on November 22, 1904, De Bock was a prominent painter and etcher associated with the later phase of the Hague School. His work is characterized by a deep sensitivity to the nuances of the Dutch landscape, rendered often in melancholic yet harmonious tones, capturing the unique interplay of light, water, and sky that defines the Netherlands. Though perhaps not as internationally renowned as some of his contemporaries, his contributions, particularly his landscape paintings and his involvement in the monumental Panorama Mesdag, secure his place in Dutch art history.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Théophile de Bock's journey into the art world was not immediate. Initially, he pursued a career that seemed far removed from the painter's studio, working for the Hollandsche IJzeren Spoorweg-Maatschappij (Dutch Railway Company). However, the allure of art proved too strong. His passion for drawing and painting reportedly consumed his time, leading to his dismissal from the railway position. This event, while perhaps a setback at the time, ultimately freed him to dedicate his life entirely to his artistic calling. The Hague, his birthplace, with its proximity to the dunes, polders, and woods that would become his primary subjects, provided the perfect environment for his burgeoning talent.

His formal artistic training began under the landscape painter J.W. van Borselen (Jan Willem van Borselen). He also received guidance from Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch, another stalwart of the Hague School, known for his luminous beach and water scenes. These early mentors instilled in him the foundational principles of landscape painting prevalent in their circle. However, it was the pervasive influence of Jacob Maris, one of the leading figures of the Hague School, that would most profoundly shape De Bock's mature style. The atmospheric depth and tonal subtlety found in Maris's work resonated deeply with De Bock's own artistic sensibilities.

The Hague School Context

To fully appreciate Théophile de Bock's work, one must understand the artistic milieu in which he operated: the Hague School. Flourishing roughly between 1860 and 1890, this movement represented a significant shift in Dutch art. Reacting against the idealized and often overly romanticized landscapes of the preceding generation, Hague School artists sought a more realistic, truthful depiction of their surroundings. They were drawn to the everyday Dutch landscape – the canals, windmills, fishing villages, polders, and heathlands – rendered with a focus on mood and atmosphere rather than precise detail.

Key figures of the Hague School included Jozef Israëls, often considered the doyen of the group, known for his poignant scenes of peasant and fisherfolk life; Anton Mauve, a master of pastoral landscapes often featuring sheep, and a cousin-in-law and early mentor to Vincent van Gogh; Willem Roelofs, one of the pioneers who brought influences from the French Barbizon School back to the Netherlands; and the three Maris brothers – Jacob, Matthijs, and Willem. Jacob Maris excelled in powerful, cloudy Dutch skies and townscapes, Matthijs pursued a more mystical, dreamlike path, and Willem focused on lush, watery landscapes with cattle.

The Hague School artists shared an affinity for tonal painting, often employing a palette dominated by greys, browns, and muted greens to capture the specific light and humid atmosphere of the Netherlands. They were heavily influenced by the French Barbizon School painters, such as Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, and Théodore Rousseau, who similarly advocated for painting directly from nature (en plein air) and capturing realistic rural scenes. De Bock entered this vibrant scene, absorbing its principles while developing his own distinct voice.

De Bock's Artistic Style: Mood and Atmosphere

Théophile de Bock carved his niche within the Hague School primarily as a landscape painter. His work is often characterized by a certain lyrical melancholy, a quiet contemplation of nature. While influenced by Jacob Maris, De Bock developed a style that was recognizably his own. He paid considerable attention to composition and the balance of proportions within his canvases, creating harmonious arrangements of land, water, and sky. His handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) was subtle yet effective, contributing to the overall mood of his pieces.

A distinctive feature of De Bock's palette is his frequent use of silvery grey tones, particularly effective in rendering the overcast skies and watery reflections typical of the Dutch climate. Alongside these greys, he employed fresh, vibrant greens, especially in his depictions of wooded areas, capturing the lushness of foliage. His brushwork, while grounded in the realism of the Hague School, often possessed an impressionistic quality, suggesting forms and textures rather than delineating them with sharp precision. He aimed to convey the feeling, the atmosphere, the stemming of a place, rather than a mere topographical record.

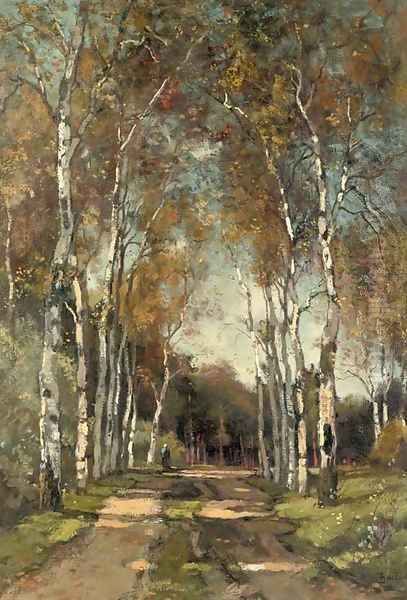

His preferred subjects were the landscapes around The Hague, the Veluwe region known for its forests and heathlands, and the dune areas near the coast. Woods, lanes bordered by trees (especially birches), quiet canals, and expansive dune landscapes feature prominently in his oeuvre. He sought out the tranquil and unspoiled aspects of nature, often imbuing his scenes with a sense of stillness and solitude. Unlike some contemporaries who focused on peasant life or bustling cityscapes, De Bock remained predominantly a painter of pure landscape.

Representative Works and Themes

While a comprehensive catalogue of De Bock's work is complex due to varying titles and dispersed collections, several paintings stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns. Wooded Landscape (circa 1880) exemplifies his skill in capturing the dappled light filtering through trees and the rich textures of the forest floor. The interplay of light and shadow, rendered in his characteristic greens and earthy tones, creates a sense of depth and enclosure.

The Picknick (1890) offers a slightly different perspective, incorporating figures into the landscape, yet nature remains the dominant element. The scene likely depicts a leisurely moment, but the focus remains on the rendering of the natural setting, the quality of light, and the overall atmosphere. Such works demonstrate his ability to integrate human presence subtly within the broader scope of the landscape.

Other typical subjects include paintings simply titled Birch Lane, Landscape near Loosduinen, or Canal in Winter. These titles reflect his direct engagement with the specific locales he frequented. His winter scenes often showcase his mastery of tonal variations, capturing the stark beauty of the Dutch landscape under snow or frost with a limited yet expressive palette. His depictions of birch trees were particularly admired, capturing their slender elegance and distinctive bark.

Collaboration on the Panorama Mesdag

One of the most significant undertakings in Théophile de Bock's career was his participation in the creation of the Panorama Mesdag. Unveiled in 1881, this colossal cylindrical painting remains a major attraction in The Hague. The project was initiated and largely executed by Hendrik Willem Mesdag, the preeminent marine painter of the Hague School, famous for his depictions of the North Sea and the fishing fleet at Scheveningen.

The Panorama Mesdag offers a breathtaking 360-degree view of the sea, the dunes, and the fishing village of Scheveningen as it appeared around 1880. Given the immense scale of the canvas (over 14 meters high and 120 meters in circumference), Mesdag enlisted help from fellow artists. His wife, Sientje Mesdag-van Houten, a talented painter in her own right, contributed to the depiction of the village. The figure painter Barend Blommers is also often credited with assisting, possibly with some of the figures populating the scene.

Théophile de Bock was entrusted with a crucial part of the panorama: painting the vast expanse of sky and the dune landscape that forms the foreground transition from the viewing platform to the painted scene. This was a task well-suited to his skills. His ability to render atmospheric effects, cloud formations, and the specific textures and colours of the dunes was essential to the overall illusion and success of the panorama. His contribution seamlessly integrates with Mesdag's powerful depiction of the sea and beach, creating a unified and immersive experience. His involvement in this iconic work cemented his reputation within the Hague School circle.

Connections with Contemporaries: Van Gogh and Others

Théophile de Bock moved within a network of prominent artists. His collaboration on the Panorama Mesdag brought him into close working contact with Hendrik Willem Mesdag, Sientje Mesdag-van Houten, and Barend Blommers. His training connected him to J.W. van Borselen and J.H. Weissenbruch, and his style showed the clear influence of Jacob Maris. He was an active participant in the artistic life of The Hague, likely associated with societies like the Pulchri Studio, a hub for Hague School artists.

An intriguing connection exists with Vincent van Gogh. Van Gogh, during his time in The Hague (1881-1883), was keenly aware of the established Hague School painters. He admired Anton Mauve but had more complex, sometimes critical, views of others. In his letters, particularly those to his friend Anthon van Rappard, Van Gogh mentions De Bock on several occasions. In one letter (Letter 294, circa December 1882), Van Gogh critiques a De Bock painting, finding it too derivative of the seventeenth-century master Jacob van Ruisdael, a common point of reference for landscape painters.

In another letter (Letter 366, July 1883), Van Gogh recounts seeing De Bock on the street, noting his "velvet jacket" and prosperous appearance, perhaps hinting at a perceived gap between De Bock's establishment success and Van Gogh's own struggles. While Van Gogh acknowledged De Bock's ability, his comments suggest a certain critical distance, perhaps reflecting differing artistic temperaments and goals. These mentions, however, underscore De Bock's visibility and status within the Dutch art scene of the time. His influence extended to the point where several streets in Dutch towns were later named in his honour, a testament to his public recognition.

De Bock as an Etcher

Beyond his significant output as a painter, Théophile de Bock was also a capable and productive etcher. Etching, a printmaking technique involving drawing onto a metal plate coated with wax, then etching the lines with acid, was practiced by many Hague School artists. It allowed for a different kind of expression, often more linear and intimate than painting.

De Bock's etchings typically mirrored the subjects of his paintings: landscapes, wooded scenes, canals, and dunes. He translated his sensitivity to atmosphere and light into the black and white medium of print. His etched lines could be delicate and precise or broader and more suggestive, depending on the desired effect. Etching allowed for wider dissemination of his imagery, contributing to his reputation among collectors and fellow artists. His work in this medium forms an important, though perhaps less widely known, part of his artistic legacy, demonstrating his versatility across different techniques.

Later Life and Legacy

Théophile de Bock continued to paint and exhibit throughout his career, remaining associated with the Hague School aesthetic even as newer trends like Amsterdam Impressionism, championed by artists such as George Hendrik Breitner and Isaac Israëls (son of Jozef), began to emerge towards the end of the century. He maintained a reputation as a skilled and sensitive interpreter of the Dutch landscape.

Despite his contributions and recognition during his lifetime, including his key role in the Panorama Mesdag, De Bock's fame has perhaps been somewhat eclipsed posthumously by figures like the Maris brothers, Mauve, Weissenbruch, and of course, the towering international figure of Van Gogh. Some critics and historians have noted that his works can occasionally appear repetitive or overly reliant on established formulas, particularly when compared to the innovative power of some contemporaries. His works appear less frequently on the art market compared to those of the top-tier Hague School masters, contributing to a sense that he is somewhat "forgotten" by the broader public.

However, within the specialized field of Dutch art history, his importance is acknowledged. He represents a significant strand within the Hague School, particularly its focus on pure landscape and atmospheric rendering. His influence on younger landscape painters and his consistent dedication to capturing the specific moods of the Dutch environment are undeniable. The recent discovery of photographs potentially taken by De Bock has also opened new avenues for research, suggesting a possible interest in using photography as an aid or parallel practice to his painting, a topic common among artists of that era.

Conclusion: An Enduring Voice of the Dutch Landscape

Théophile de Bock died relatively young, at the age of 53, in 1904. He left behind a substantial body of work that captures the essence of the Dutch landscape through the lens of the Hague School's tonal realism and atmospheric sensitivity. While perhaps lacking the dramatic power of Jacob Maris or the poignant social commentary of Jozef Israëls, De Bock possessed a unique ability to convey the quiet, lyrical beauty of his native land. His silvery skies, tranquil woods, and expansive dunes, rendered with subtle colour harmonies and a keen sense of composition, continue to resonate with viewers.

His crucial contribution to the iconic Panorama Mesdag ensures his name remains linked to one of the Netherlands' most cherished artistic monuments. His interactions and connections with figures like the Mesdags, Jacob Maris, and even the critical eye of Van Gogh, place him firmly within the central narrative of late nineteenth-century Dutch art. Though the currents of art history may sometimes shift focus, Théophile de Bock remains an important figure, an artist whose dedicated observation and sensitive brushwork created enduring images of the Netherlands' natural charm. He deserves recognition as a key member of the Hague School and a painter who masterfully captured the soul of the Dutch landscape.