Thomas Creswick stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. A painter and illustrator celebrated primarily for his depictions of the English and Welsh countryside, Creswick captured the nuances of nature with a dedication that earned him considerable acclaim during the Victorian era. His work, characterised by its detailed realism and gentle, observant eye, offers a window into the pastoral ideals and artistic sensibilities of his time. As a member of the prestigious Royal Academy and a key figure associated with the Birmingham School of landscape artists, his career reflects both personal artistic achievement and broader trends within British art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

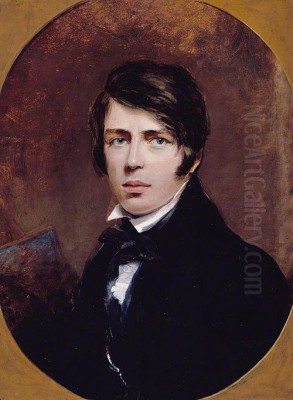

Thomas Creswick was born on February 5, 1811, in Sheffield, which was then situated in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England. His parents were Thomas Creswick senior and Mary Epworth. His early education took place at Hazelwood School, located near Birmingham, a city rapidly becoming an industrial powerhouse but also fostering a vibrant artistic community. It was in Birmingham that the young Creswick began his formal artistic training.

His primary instruction in painting came from John Vincent Barber, a respected Birmingham artist and drawing master. Barber was himself part of a lineage of Birmingham artists known for their landscape work. Under Barber's guidance, Creswick honed his skills in drawing and observation, developing the foundational techniques that would underpin his later career. This period in Birmingham was crucial, immersing him in an environment where the direct study of nature was increasingly valued.

Seeking broader opportunities and recognition, Creswick relocated to London around 1828. This move marked the beginning of his professional career on the national stage. London was the undeniable centre of the British art world, offering access to major exhibitions, patrons, and fellow artists. His arrival coincided with a period of great vitality in British landscape painting, following the towering achievements of artists like John Constable and J.M.W. Turner.

Launching a Career in London

Creswick wasted little time in establishing his presence in the competitive London art scene. As early as 1827, while possibly still based primarily in Birmingham or transitioning, he exhibited work at the Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. This initial exposure was followed by a more significant step in 1828 when he submitted two paintings to the prestigious annual exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts.

These debut works at the Academy were titled Llyn Gwynant, Morning and Carnarvon Castle. Both subjects indicate his early interest in Welsh scenery, a theme that would recur throughout his career. Wales, with its dramatic mountains, valleys, and rivers, offered the kind of picturesque and sublime landscapes that appealed greatly to Romantic and Victorian sensibilities. Submitting to the Royal Academy was a critical move for any ambitious young artist, as its exhibitions were the most important showcase in the country.

His early works quickly demonstrated his commitment to careful observation and detailed rendering. He focused on capturing the specific textures of rock, foliage, and water, and the subtle effects of light and atmosphere. This dedication to naturalistic detail distinguished his work and began to attract favourable notice from critics and the public. He became a regular contributor to the Royal Academy exhibitions, steadily building his reputation year by year.

Artistic Style: Realism and the Love of Nature

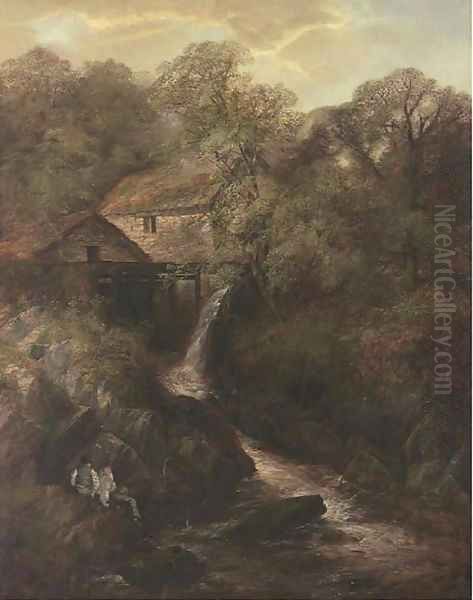

Thomas Creswick's artistic style is best described as a form of detailed realism, deeply rooted in his affection for the natural world. He primarily painted landscapes, focusing on the gentler, more pastoral aspects of the British countryside rather than overtly dramatic or sublime vistas, although he did depict mountainous regions of Wales and Northern England. His work exudes a sense of tranquility and harmony.

A key characteristic of his style is the meticulous attention to detail. Creswick rendered trees, foliage, rocks, and water with painstaking care, striving for botanical and geological accuracy. This approach aligned with the growing Victorian interest in science and natural history, and particularly resonated with the influential art critic John Ruskin, who championed "truth to nature." Ruskin admired Creswick's ability to capture the intricate forms and textures found in the landscape.

His compositions are typically well-structured and balanced, often featuring winding streams or rivers leading the viewer's eye into the scene. Trees frequently frame the view, creating a sense of enclosure and intimacy. While his subjects were drawn directly from nature, his compositions often possess a carefully arranged, almost idyllic quality, reflecting the picturesque tradition inherited from earlier landscape painters. Figures and animals, when included, are usually small elements within the larger landscape, emphasizing the dominance of nature.

Creswick's colour palette is often noted for its subtlety and restraint. He favoured cool, silvery greens, soft greys, and earthy browns, creating a harmonious and often slightly muted effect. While capable of depicting bright sunlight, many of his works capture the softer light of overcast days or the gentle illumination of morning or evening. This tonal control contributes significantly to the peaceful and contemplative mood prevalent in his paintings. His brushwork is generally precise and controlled, allowing for the clear definition of forms.

Favourite Themes: Rivers, Woodlands, and Rural England

Throughout his career, Creswick returned repeatedly to certain favoured themes and locations, primarily drawn from the landscapes of England and Wales. He showed a particular fondness for depicting rivers and streams, capturing the movement of water over rocks, the reflections on its surface, and the lush vegetation along its banks. Titles such as The Stream through the Wood or paintings featuring specific rivers like the Wharfe or the Tees are common in his oeuvre.

Woodland scenes were another staple. He excelled at portraying the complex structure of trees, the textures of bark, and the delicate tracery of leaves. His woodland interiors often convey a sense of quiet seclusion, inviting the viewer into a peaceful natural sanctuary. These works showcase his skill in handling light filtering through foliage and creating depth within a dense environment.

Beyond specific natural features, Creswick celebrated the quintessential English rural landscape – rolling hills, quiet valleys, rustic cottages, and country lanes. His paintings often evoke a sense of timelessness and stability, presenting an idealized vision of rural life that appealed strongly to urban Victorian audiences seeking respite from the rapid changes brought by industrialization. North Wales, Derbyshire, Yorkshire, and Devon were among his frequent sketching grounds.

His dedication to these themes was unwavering. He spent considerable time sketching outdoors, gathering material directly from nature, which he would then work up into finished paintings in his studio. This practice of direct observation, combined with careful studio execution, was central to his method and ensured the convincing naturalism of his work.

Notable Works: Capturing the Essence of the Landscape

While Creswick produced a large body of work, several paintings stand out as particularly representative of his style and achievements. Although specific titles can sometimes vary or refer to similar subjects, certain works received significant attention during his lifetime and remain key examples of his art.

England (1847) is often cited as a quintessential Creswick landscape, embodying his vision of the tranquil English countryside. Such broadly titled works typically synthesized his observations into an idealized yet believable scene, likely featuring gentle hills, mature trees, and perhaps a meandering stream or quiet pool.

A Passing Shower (1849) demonstrates his skill in capturing atmospheric effects. Victorian artists were fascinated by weather, and Creswick adeptly portrayed the changing light and dampness associated with transient rain showers, adding a layer of dynamism to the landscape.

The Evening Walk (date uncertain, but exhibited mid-century) is held by the Tate collection (formerly National Gallery). This work likely exemplifies his ability to render the soft, diffused light of dusk and evoke a peaceful, contemplative mood, possibly featuring figures strolling through a serene landscape setting.

Other typical titles that recur and represent his focus include The Windings of a River, Mountain Lake, North Wales, A Rocky Stream, In the Welsh Mountains, and The Old Tree. Works like The Nut-brown Maid were praised specifically by critics like Ruskin for the intricate rendering of foliage and the handling of light, showcasing his technical prowess in representing complex natural forms.

These paintings, whether depicting specific locations or more generalized pastoral scenes, consistently reflect Creswick's commitment to detailed observation, harmonious composition, and the celebration of the quiet beauty of the British landscape. They secured his reputation among collectors and fellow artists during the Victorian period.

Creswick the Illustrator

Beyond his easel paintings, Thomas Creswick was also a highly regarded and prolific illustrator. Book illustration flourished in the Victorian era, driven by advances in printing technology and a growing reading public. Creswick contributed to numerous publications, bringing his landscape sensibility to the printed page.

His illustrations often appeared as steel engravings or wood engravings, translating his detailed drawing style into line work suitable for reproduction. He frequently collaborated with skilled engravers who translated his designs. His landscape illustrations were particularly sought after for poetry collections, travelogues, and gift books.

Among the notable books featuring his work are editions of Oliver Goldsmith's The Deserted Village, Milton's L'Allegro, and collections such as Early English Poems. His ability to evoke mood and atmosphere through landscape made his illustrations particularly effective accompaniments to poetry. He could create vignettes that captured the essence of a verse or provided a scenic backdrop that enhanced the text's meaning.

He also contributed significantly to topographical works. His illustrations for Ireland, its Scenery, Character, &c. (published by Mr. and Mrs. S.C. Hall) provided visual representations of Irish landscapes. Similarly, he collaborated on Wanderings and Excursions in North Wales by Thomas Roscoe, working alongside other prominent artists like J.M.W. Turner and David Roberts on this project, providing views like Dolbadarn Bridge. These topographical illustrations required accuracy while still allowing for artistic interpretation, playing to Creswick's strengths.

His work as an illustrator broadened his reach and influence, making his vision of the landscape accessible to a wider audience beyond those who could afford original paintings. It also demonstrated his versatility as an artist, comfortable working across different media and formats.

Collaborations with Fellow Artists

A fascinating aspect of Creswick's career was his frequent collaboration with other artists, particularly those specializing in figures and animals. While Creswick was a master of landscape, he sometimes felt his scenes would benefit from the addition of narrative elements or livelier fauna than he typically included himself. This practice of collaboration was not uncommon in the 19th century, allowing artists to combine their respective strengths.

He worked with several well-known Royal Academicians on joint canvases. Richard Ansdell, a painter celebrated for his depictions of animals, often added dogs, sheep, or sporting figures to Creswick's landscapes. Thomas Sidney Cooper, renowned as England's foremost cattle painter, contributed his signature cows and sheep to Creswick's pastoral settings, creating works that appealed strongly to the rural tastes of many patrons.

Figure painters also collaborated with Creswick. William Powell Frith, famous for his bustling contemporary life scenes like Derby Day, occasionally painted figures into Creswick's landscapes early in his career. Frederick Goodall, known for his historical and biblical scenes as well as rustic genre, also added figures to Creswick's settings. Other collaborators included Augustus Egg and Alfred Elmore, both accomplished figure and historical painters.

These collaborations resulted in paintings where the landscape provided a detailed and atmospheric setting for the figures or animals supplied by the specialist painter. While successful commercially, this practice sometimes drew criticism, suggesting a lack of confidence or completeness in Creswick's own abilities. However, it can also be viewed as a pragmatic approach, leveraging the specific talents of his peers to create richer, more varied compositions that catered to market demands. These joint works underscore the interconnectedness of the London art world and the specialization that characterized much Victorian painting.

Recognition: The Royal Academy and Beyond

Thomas Creswick's career trajectory was marked by steady recognition within the established art institutions of his day, culminating in full membership of the Royal Academy. His election as an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) came in 1842, a significant milestone confirming his rising status. This was followed by his election as a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1851 (some sources state 1850, but 1851 is more commonly cited for the full RA election), placing him among the elite of the British art world.

Membership in the Royal Academy brought considerable prestige and professional advantages. RAs had preferential treatment in the hanging of works at the annual Summer Exhibition, the most important art event of the year. They also participated in the governance of the Academy and its schools. Creswick remained a loyal and consistent exhibitor at the RA throughout his career, showcasing the majority of his major works there.

His paintings were popular with Victorian collectors, particularly the growing middle class who appreciated his accessible, naturalistic style and idealized depictions of the British countryside. His work entered numerous private collections. Public recognition also grew. A posthumous exhibition dedicated to his work was held as part of the London International Exhibition of 1873, featuring 109 of his oil paintings and watercolours, a testament to his productivity and esteem.

His work also entered public collections. The Evening Walk, mentioned earlier, became part of the national collection (now Tate Britain). Other museums in the UK, such as the Sheffield Museums Trust (in his birthplace) and regional galleries, also hold examples of his work, ensuring his art remains accessible for study and appreciation.

The Birmingham School Connection

While Creswick spent most of his professional life in London, his roots and early training connected him to what became known as the Birmingham School of landscape artists. This was not a formal institution but rather a group of artists active in the early to mid-19th century, centred around Birmingham, who shared an interest in depicting the local scenery of the Midlands, Wales, and the North of England with naturalistic detail.

The most famous artist associated with this group is David Cox (1783-1859), known for his vigorous and atmospheric watercolours and later oils. Thomas Baker (1809-1869), known as "Baker of Leamington," was another key figure, specializing in detailed, often brightly lit, views of Warwickshire and the Midlands. Creswick, having studied with Barber in Birmingham and sharing the group's focus on direct observation and British scenery, is considered an important member of this school, particularly in its earlier phase before his move to London.

The Birmingham artists emphasized sketching outdoors and capturing the specific character of the British landscape. They often favoured less dramatic scenery than that sought by followers of the sublime tradition, focusing instead on the quiet beauty of woodlands, rivers, and farmland. Creswick's work, with its meticulous detail and focus on English and Welsh subjects, aligns well with these characteristics, even as his style evolved within the London art scene. His connection to the Birmingham School highlights the regional vitality of British art during this period.

Critical Reception and John Ruskin's Praise

Thomas Creswick's work generally received positive reviews during his lifetime, appreciated for its technical skill, pleasant subject matter, and faithfulness to nature. He was seen as a reliable and accomplished landscape painter within the mainstream tradition. However, the most significant critical commentary on his work came from the influential writer and art critic John Ruskin.

In his seminal work Modern Painters, Ruskin frequently discussed contemporary landscape artists, evaluating them based on his principle of "truth to nature." Ruskin admired Creswick's meticulous rendering of natural details, such as foliage, rocks, and water. He praised Creswick's "loving fidelity" and the "real, right-forward, straightforward landscape work" found in his paintings. For Ruskin, Creswick's careful observation represented a positive contrast to the generalized or artificial conventions of earlier landscape painting.

Ruskin specifically lauded Creswick's depiction of foliage, noting the complexity and accuracy in works like The Nut-brown Maid. He saw in Creswick an artist who genuinely studied and understood the natural forms he painted. This praise from Ruskin undoubtedly boosted Creswick's reputation, aligning him with the critic's influential ideas about the moral and aesthetic importance of detailed naturalism in art.

However, Ruskin's praise was not entirely unqualified. While appreciating his detail, Ruskin sometimes found Creswick's overall compositions or colour lacking the imaginative power or emotional depth he admired in artists like J.M.W. Turner. Nevertheless, Ruskin's positive assessment of Creswick's observational skills and honesty cemented his place as a respected figure in Victorian landscape art.

Context: Contemporaries and the Victorian Art World

To fully appreciate Thomas Creswick's position, it's helpful to consider him alongside his contemporaries in the vibrant Victorian art world. Landscape painting was immensely popular, ranging from the dramatic Romanticism of the aging J.M.W. Turner to the detailed naturalism favoured by the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in their landscape work.

Creswick occupied a space somewhat between these poles. He was less revolutionary than Turner or the Pre-Raphaelites like John Everett Millais (in his landscape phase) but more detailed and less broadly atmospheric than predecessors like John Constable. His contemporaries in landscape included Clarkson Stanfield, known for his marine paintings and dramatic landscapes; William Collins, who often incorporated genre elements into coastal and rural scenes; Francis Danby, who painted poetic and sometimes apocalyptic landscapes; and John Linnell, whose visionary landscapes often had a religious undertone.

His collaborators, like Richard Ansdell, Thomas Sidney Cooper, and William Powell Frith, were major figures in their respective genres of animal and figure painting. Sir Edwin Landseer dominated animal painting with dramatic and anthropomorphic depictions. The art world was centred around the Royal Academy, but other institutions like the Society of British Artists and various watercolour societies also played important roles. The rise of commercial galleries and print publishers further shaped the market. Creswick navigated this complex world successfully, maintaining a consistent style and output that found favour with institutions, critics like Ruskin, and the buying public.

Personal Glimpses: Character and Anecdotes

While historical records focus primarily on his professional life, some glimpses of Thomas Creswick's personality emerge from contemporary accounts. He was generally regarded as amiable and was part of the social circles frequented by fellow artists in London. His love for nature was evident not just in his paintings but in his practice of spending significant time sketching outdoors in his favoured regions of England and Wales.

One famous, though perhaps slightly exaggerated, anecdote concerns his personal habits. His friend and collaborator William Powell Frith, in his memoirs, affectionately referred to Creswick with the nickname "The Great Unwashed," suggesting a certain disregard for personal ablutions. While likely intended humorously, this detail paints a picture of an artist perhaps more focused on his work and immersion in nature than on social niceties, or simply reflecting the different standards of hygiene of the time.

He was also known for his sense of humour. Despite the often serene and serious nature of his finished paintings, accounts suggest a man capable of wit and good company. His collaborations indicate a willingness to work closely with others, suggesting a degree of sociability and pragmatism. Overall, the impression is of a dedicated artist, deeply passionate about the natural world, who achieved significant success through talent and consistent hard work within the established structures of the Victorian art world.

Later Years and Legacy

Thomas Creswick continued to paint and exhibit regularly throughout the 1850s and 1860s, maintaining his characteristic style. His health reportedly declined in his later years, which may have impacted his productivity towards the very end of his life. He died at his home in Bayswater, London, on December 28, 1869, at the age of 58. He was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery.

His legacy lies in his contribution to the tradition of British landscape painting during a period of significant change and development. He represented a form of detailed, naturalistic landscape art that was highly popular in the mid-Victorian era, bridging the gap between the broader handling of earlier Romantics like Constable and the intense, hyper-realism of the Pre-Raphaelites. His work satisfied a public desire for recognizable, skillfully rendered views of the national landscape, presented with a gentle, often idealized, sensibility.

While his reputation may have been overshadowed in the longer term by more innovative or dramatic figures like Turner or Constable, Creswick remains an important artist for understanding the mainstream tastes and artistic values of the Victorian period. His dedication to "truth to nature," praised by Ruskin, aligned him with key critical currents of the time. His numerous works, both paintings and illustrations, provide a rich visual record of the English and Welsh countryside as seen through the eyes of a skilled and sensitive observer. His position as a Royal Academician and his association with the Birmingham School further solidify his place in the annals of British art history.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of Nature

Thomas Creswick RA carved out a distinguished career as one of Victorian England's most respected landscape painters. Born from the artistic milieu of Birmingham and rising to prominence within the London art world and the Royal Academy, he dedicated his art to the faithful and affectionate depiction of the British countryside. His style, marked by meticulous detail, subtle colour harmonies, and tranquil compositions, captured the quiet beauty of rivers, woodlands, and rural scenes.

Through his numerous paintings and widely circulated illustrations, Creswick helped shape the Victorian perception of the national landscape. His collaborations with figure and animal painters like Ansdell, Cooper, and Frith highlight the specialized nature of the art market, while his endorsement by John Ruskin underscored the contemporary appreciation for naturalistic accuracy. Though perhaps lacking the revolutionary vision of some contemporaries, Creswick's consistent quality, his genuine love for nature, and his ability to create serene and accessible images earned him lasting recognition. His work remains a valuable testament to the enduring appeal of the pastoral landscape in British art.