Thomas Herbst stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of German art at the turn of the 20th century. Born in the bustling port city of Hamburg in 1848 and passing away there in 1915, Herbst dedicated his life to capturing the nuanced beauty of the natural world, particularly the landscapes and rural life of Northern Germany. He was a key proponent of plein-air painting and a vital force in the development of Impressionism in his native region, leaving behind a body of work celebrated for its atmospheric depth, sensitive handling of light, and honest depiction of his surroundings.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Thomas Herbst's journey into the world of art began in his birthplace, Hamburg. Showing early promise, he initially received instruction from Günther Gensler, a respected local artist. Seeking broader training, Herbst moved to Frankfurt am Main, where he enrolled at the renowned Städel Art Institute. There, he studied under Jakob Becker, absorbing the tenets of academic painting prevalent at the time. His quest for knowledge and refinement of his skills led him further, first to Berlin, where he learned from the influential history and portrait painter Karl Gussow at the Prussian Academy of Arts.

Following his time in Berlin, Herbst relocated to Weimar, another important artistic center. He joined the Weimar Saxon Grand Ducal Art School, studying under the Belgian painter Charles Verlat. Verlat, known for his animal paintings and historical scenes, likely imparted valuable lessons in observation and technique. This period exposed Herbst to different pedagogical approaches and artistic currents, broadening his perspective beyond the confines of a single school or style. Each stage of his education contributed layers to his developing artistic identity, providing a solid foundation upon which he would later build his distinctive impressionistic approach.

Munich, Paris, and Formative Travels

The late 1870s marked a crucial phase in Herbst's development. He spent time in Munich, a vibrant hub for artistic innovation in Germany. While there, he came into contact with the circle around Wilhelm Leibl. Leibl and his associates, including artists like Wilhelm Trübner, championed a form of realism focused on direct observation and unidealized depictions of everyday life, particularly rural subjects. This exposure undoubtedly resonated with Herbst's own inclinations towards capturing the tangible world, influencing his brushwork and subject matter, steering him away from purely academic conventions.

Herbst also undertook a brief but significant stay in Paris around 1877. While direct evidence of his engagement with the French Impressionists during this short period is limited, the artistic ferment of the French capital, where Impressionism was gaining momentum, could hardly have failed to make an impression. More impactful, perhaps, were his travels to the Netherlands. Accompanied at times by fellow artist Max Liebermann, Herbst immersed himself in the Dutch landscape and studied the works of the Hague School painters, such as Anton Mauve and Jozef Israëls. The Dutch masters' sensitivity to light, atmosphere, and rural scenery deeply informed his own evolving plein-air practice. He also travelled to Italy, further expanding his visual repertoire.

The Emergence of an Impressionist Style

Returning from his travels and studies, Thomas Herbst began to synthesize his experiences into a unique artistic voice. While rooted in the realist tradition encountered in Munich, his style progressively loosened, embracing the principles of Impressionism. He became a dedicated practitioner of plein-air painting, working directly outdoors to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. His brushwork grew more visible and dynamic, applying paint in distinct strokes that conveyed texture and vibrancy rather than aiming for a smooth, polished finish.

Herbst's primary focus became the landscape, particularly the environs of his native Hamburg and the marshlands of Northern Germany. He possessed a remarkable ability to render the specific quality of light in these regions – the soft, diffused light filtering through clouds, the bright reflections on water, or the warm glow of a setting sun across a field. His color palette became brighter and more nuanced, reflecting the direct observation of nature's hues under varying conditions. Unlike some of his contemporaries who tackled urban scenes or society portraits, Herbst remained deeply connected to the rural world, finding profound beauty in its simplicity and rhythms.

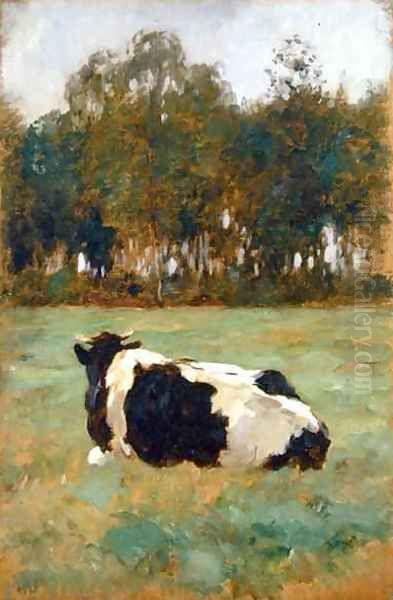

"Kuhherbst": Master of Bovine Subjects

A distinctive feature of Thomas Herbst's oeuvre, and one that earned him the affectionate, if slightly limiting, nickname "Kuhherbst" (Cow Herbst), was his frequent and masterful depiction of cattle. Far from being mere pastoral accessories, the cows in Herbst's paintings are often central figures, rendered with empathy and keen observation. He studied their forms, movements, and integration within the landscape, capturing them grazing peacefully in meadows, resting by water, or being herded along country lanes.

His interest in cattle connected him to a long tradition of animal painting, influenced perhaps by his teacher Charles Verlat and the Dutch masters he admired. However, Herbst approached the subject with an Impressionist sensibility. He was less concerned with anatomical precision in the academic sense and more interested in how the animals' forms interacted with light and shadow, how their hides reflected the surrounding colors, and how they contributed to the overall atmosphere of the scene. Works like Ochsen am Wasser (Oxen by the Water) exemplify his skill in portraying these animals as integral parts of the living landscape, imbued with a quiet dignity.

Hamburg and the Künstlerklub

Upon settling back in Hamburg, Thomas Herbst became a respected member of the city's artistic community. While described as modest and somewhat reserved, his dedication to his craft and his pioneering adoption of Impressionist techniques made him influential. A pivotal moment came in 1897 with the founding of the Hamburgischer Künstlerklub (Hamburg Artists' Club). Herbst was a co-founder alongside fellow artists such as Ernst Eitner, Arthur Illies, and Julius von Ehren.

This club served as a crucial forum for progressive artists in Hamburg, providing a space for mutual support, discussion, and the promotion of modern art trends, particularly plein-air painting and Impressionism. Alfred Lichtwark, the visionary director of the Hamburg Kunsthalle (Art Museum), was a key supporter and promoter of the club and its members, including Herbst. Lichtwark recognized the quality and importance of Herbst's work and helped bring it to wider attention through acquisitions and exhibitions. Herbst's involvement in the Künstlerklub solidified his position as a leading figure in the Hamburg art scene, fostering a local environment receptive to modern artistic developments.

Representative Works

Thomas Herbst's legacy is preserved through numerous paintings that capture the essence of his artistic vision. While specific titles vary in sources, several key works and themes are consistently associated with him:

Ochsen am Wasser (Oxen by the Water): This subject, which he revisited, showcases his skill in depicting cattle within an atmospheric, light-filled landscape setting, often featuring reflections in water.

Frühling in der Marsch (Spring in the Marsh): Paintings with this theme highlight his sensitivity to the changing seasons and the specific character of the North German marshlands, rendered with fresh colors and lively brushwork.

Kühe auf der Weide (Cows in the Pasture): Numerous works depict this quintessential rural scene, demonstrating his deep familiarity with his bovine subjects and the interplay of light across open fields.

Holländische Landschaft (Dutch Landscape): Reflecting his travels, these works capture the flat terrains, canals, and distinctive light of the Netherlands, often compared to the works of the Hague School.

Views of Hamburg and its Environs: Herbst also painted scenes closer to his urban home, including views of the Alster lake or glimpses of the city's architecture, like Blick auf St. Michaelis (View of St. Michael's Church), always filtered through his impressionistic lens focused on atmosphere and light.

These works collectively demonstrate Herbst's commitment to direct observation, his mastery of light and color, and his deep connection to the landscapes and rural life of his native region.

Contemporaries and Artistic Network

Thomas Herbst operated within a rich network of artists, teachers, and promoters who shaped the German art world of his time. Understanding these connections helps place his work in context:

Teachers: His early training involved Günther Gensler, Jakob Becker, Karl Gussow, and Charles Verlat, each contributing to his technical foundation.

Munich Realists: The influence of Wilhelm Leibl and Wilhelm Trübner during his time in Munich steered him towards realism and direct observation.

German Impressionist "Triumvirate": Herbst is often discussed in relation to the leading figures of German Impressionism: Max Liebermann (with whom he travelled), Lovis Corinth, and Max Slevogt. While perhaps less nationally famous, Herbst was a crucial pioneer alongside them, particularly for Northern Germany.

Hamburg Artists' Club: His co-founders and colleagues included Ernst Eitner, Arthur Illies, Julius von Ehren, and Arthur Siebelist. This group formed the core of Hamburg's modern art movement. Friedrich Ahlers-Hestermann was another younger Hamburg artist active during this period.

Promoter: Alfred Lichtwark, director of the Hamburg Kunsthalle, was indispensable in championing Herbst and other local Impressionists.

Weimar School: His time in Weimar connected him to artists like Theodor Hagen, another important German landscape painter.

Berlin Secession: Herbst exhibited with the Berlin Secession, a progressive group co-founded by Liebermann and including artists like Walter Leistikow, indicating his participation in the broader German modern art movement.

Dutch Hague School: His affinity for Dutch art connects him to painters like Anton Mauve and Jozef Israëls, whose atmospheric landscapes resonated with his own style.

This network highlights Herbst's engagement with various artistic centers and movements, from Frankfurt and Weimar realism to Munich's Leibl circle, the burgeoning Impressionism shared with Liebermann, and the specific context of the Hamburg art scene fostered by Lichtwark.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Thomas Herbst continued to paint prolifically throughout his later years, remaining dedicated to his chosen subjects and plein-air methods. He regularly exhibited his work, not only in Hamburg but also with major progressive associations like the Berlin Secession and the Munich Secession, gaining recognition beyond his home city. Despite his modest personality, his reputation as a significant landscape painter grew steadily during his lifetime.

He passed away in Hamburg in 1915, leaving behind a substantial body of work that firmly established him as a key figure in German Impressionism. While sometimes overshadowed on the national stage by the more famous trio of Liebermann, Corinth, and Slevogt, Herbst's contribution remains vital, particularly for the development of modern art in Northern Germany. His paintings are held in high regard in major German museums, especially the Hamburg Kunsthalle, which holds a significant collection.

Historical Evaluation and Influence

Art historians evaluate Thomas Herbst as a crucial bridge figure and a regional master of German Impressionism. He successfully adapted the principles of French Impressionism – the emphasis on light, color, atmosphere, and capturing fleeting moments through visible brushwork – to the specific landscapes and conditions of Northern Germany. He did so not merely by imitation, but by developing a personal style rooted in his earlier realist training and his deep connection to his environment.

His influence was most pronounced in Hamburg, where, supported by Alfred Lichtwark and active within the Künstlerklub, he helped cultivate a receptive atmosphere for modern painting. He demonstrated that Impressionist techniques could be powerfully applied to local scenery, inspiring younger artists in the region. His dedication to plein-air painting, even under the often challenging weather conditions of the North, set an example of commitment to direct observation.

Herbst's work is valued for its honesty, its lack of pretension, and its profound sensitivity to the nuances of the natural world. He captured the quiet poetry of the marshlands, the tranquil presence of grazing cattle, and the ever-shifting play of light on water and land with remarkable skill and consistency. His paintings offer a distinct sense of place, reflecting the specific character of the North German landscape in a way that remains evocative and appealing today. He stands as a testament to the richness and diversity of German art at the turn of the century.

Conclusion

Thomas Herbst carved a distinct and valuable niche within the broader movement of German Impressionism. As a dedicated plein-air painter, a sensitive observer of the North German landscape, and a master portrayer of rural life, particularly his famed cattle scenes, he created a body of work characterized by atmospheric depth and nuanced light. A co-founder of the Hamburgischer Künstlerklub and championed by Alfred Lichtwark, he played a vital role in bringing modern art currents to his native city. Though perhaps quieter than some of his contemporaries, Thomas Herbst's artistic legacy endures, celebrating the subtle beauty of the everyday natural world through an authentically German Impressionist lens.