Thomas Luny stands as one of the most significant and prolific figures in the rich history of British marine painting. Active during a period of intense naval activity and expanding global trade, from the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth century, Luny captured the essence of Britain's relationship with the sea. His works, numbering in the thousands, provide a detailed and often dramatic visual record of warships, merchant vessels, coastal landscapes, and pivotal naval engagements. Combining technical accuracy with a keen sense of atmosphere, Luny secured a lasting reputation among patrons, fellow artists, and subsequent generations of art historians.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Cornwall in 1759, Thomas Luny's early years were spent in a region intrinsically linked to the sea. This coastal upbringing likely instilled in him a deep familiarity with maritime life, ships, and the ever-changing character of the ocean and sky – elements that would dominate his artistic output. Around the age of nine or eleven, seeking greater opportunities, Luny relocated to London, the burgeoning center of the British art world.

Crucially, he entered the studio of Francis Holman (c. 1729–1784), an established marine painter. Holman himself came from a family connected to shipping, being the son of a shipmaster from St Katharine's by the Tower. This connection provided Holman, and subsequently his apprentice Luny, with an intimate understanding of ship construction and rigging, a knowledge essential for convincing marine art. Holman's tutelage provided Luny with the fundamental skills and stylistic grounding upon which he would build his own successful career.

First Steps into the Art World

Luny quickly absorbed the lessons of his master and began to develop his own artistic voice. His public debut came in 1777, when he exhibited works, including The Prospect of Madeira and Portorosso, at the Incorporated Society of Artists in London. He was still a teenager, demonstrating a precocious talent and ambition. This initial exposure was a critical step in establishing his presence within the competitive London art scene.

Just three years later, around 1780, Luny began exhibiting at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts. This marked a significant milestone, signifying his arrival as an independent artist of note. Exhibiting at the Royal Academy offered unparalleled visibility and the potential to attract wealthy patrons, including naval officers and merchants eager to commission depictions of their vessels or commemorate significant voyages and battles. His submissions during this early period already showcased his focus on maritime subjects.

The Influence of Francis Holman

The stylistic debt Luny owed to Francis Holman is particularly evident in his earlier works. Holman was known for his competent, detailed, and somewhat crisp style, often depicting vessels with meticulous attention to their structure and rigging, set against carefully rendered seas and skies. He drew upon traditions established by earlier Dutch and British marine painters like Willem van de Velde the Younger and perhaps Charles Brooking.

Luny initially adopted many of Holman's characteristics, particularly in the treatment of waves, the use of lower horizons to emphasize the sky, and the precise delineation of ships. Paintings like A small shipyard on the Thames reflect this formative influence, showcasing a clarity and attention to the working details of the maritime world that likely stemmed directly from Holman's instruction and example. While Luny would develop a more dramatic and atmospheric style later, Holman's emphasis on accuracy remained a cornerstone of his art.

Building a Reputation: London and Leadenhall Street

Establishing himself independently around 1780, Luny set up his studio in London. A pivotal connection formed during this period was with a Mr. Merle, a picture dealer and frame maker based in Leadenhall Street. This location was strategically significant, as Leadenhall Street was also the headquarters of the powerful British East India Company (EIC).

Mr. Merle proved to be an effective promoter of Luny's work, representing him for over two decades. This long-standing relationship provided Luny with a consistent outlet for his paintings and access to a network of potential buyers. The proximity to the EIC headquarters facilitated numerous commissions from Company officials, captains, and merchants who desired portraits of their ships, depictions of trading posts, or scenes from significant voyages. This patronage was crucial for Luny's financial stability and professional growth.

The East India Company Connection

The relationship with the East India Company was particularly fruitful for Luny. The EIC was a colossal entity, effectively ruling large parts of India and controlling vast trade routes. Its ships, the 'East Indiamen', were among the largest and most impressive merchant vessels of the era, often heavily armed and operating almost like warships.

Company directors, shareholders, and captains were proud of their association with the EIC and its fleet. They frequently commissioned artists like Luny to create detailed 'ship portraits' of specific East Indiamen, often shown in exotic locations or battling the elements. These paintings served not only as records but also as status symbols. It's even suggested that Mr. Merle's connections allowed Luny opportunities to sail aboard EIC ships for specific commissions or voyages, further enhancing the authenticity of his depictions.

Accuracy Forged by Experience?: The Naval Question

A recurring question in Luny's biography concerns his potential service in the Royal Navy. Some accounts suggest he served as a purser (an officer responsible for supplies and accounts) during the Napoleonic Wars, possibly alongside Captain George Tobin, who later became a friend and patron. This naval experience, if true, would undoubtedly have provided invaluable first-hand knowledge of life at sea, ship handling, and the realities of naval warfare, contributing significantly to the acclaimed accuracy of his paintings.

However, concrete documentary evidence for formal naval service remains elusive, and his consistent artistic output and exhibition record during some periods of conflict cast doubt on extended time away at sea. Regardless of whether he formally served, his close associations with naval officers like Tobin, his likely time spent observing ships in ports like London and later Teignmouth, and potential voyages on EIC vessels gave him ample opportunity to study his subjects closely. His work consistently demonstrates a deep understanding of maritime practice that convinces the viewer of its authenticity.

A Pause and a Shift: The War Years

Interestingly, Luny ceased exhibiting at the Royal Academy between 1793 and 1802. This period coincides directly with the height of the French Revolutionary Wars, a time of intense naval conflict and national uncertainty for Britain. Several factors might explain this hiatus.

The turbulent political and military climate could have disrupted the art market and patronage networks. Potential patrons might have been preoccupied with the war effort, or perhaps Luny himself was engaged in activities related to the conflict, lending credence to the naval service theories, even if unproven. Alternatively, he may have been focusing on fulfilling the numerous private commissions generated through Mr. Merle and his EIC connections, finding less need for the public exposure of the RA exhibitions during those years.

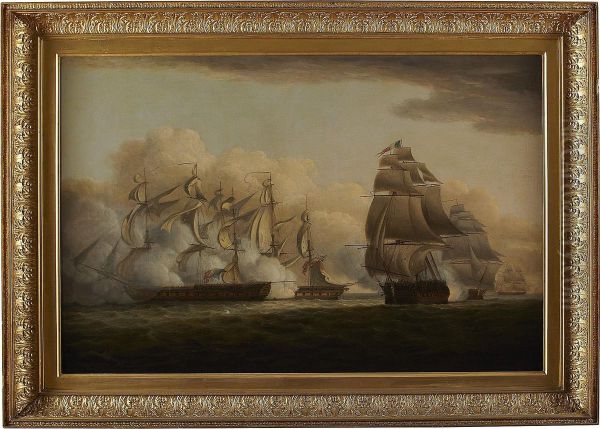

Mastering the Naval Battle

Upon resuming exhibitions and throughout his career, Luny excelled in depicting naval battles, a genre highly popular during an era defined by British sea power. His paintings captured the drama, chaos, and technical specifics of these engagements. The Battle of the Nile (1798), depicting Nelson's famous victory, is a prime example. While he likely worked from prints and accounts rather than witnessing the event, his rendition, possibly focusing on specific moments like the capture of the French ship Le Spartiate, conveys the intensity of the conflict through dynamic composition and attention to detail.

Another significant work is The Bombardment of Algiers (1816), portraying the Anglo-Dutch attack on the Barbary pirates' stronghold. These paintings were more than just illustrations; they were patriotic statements celebrating British naval prowess. Luny's ability to organize complex scenes involving multiple ships, smoke, and turbulent seas, while maintaining clarity and accuracy, set him apart. He shared this popular genre with contemporaries like Nicholas Pocock and Robert Dodd, each bringing their own style to these dramatic historical events.

Depicting Trafalgar

The Battle of Trafalgar (1805) was arguably the most celebrated British naval victory of the age, and Luny, like many artists, depicted the event. While J.M.W. Turner's famous, highly atmospheric and almost abstract rendering of Trafalgar is perhaps the best-known artistic interpretation, Luny's approach would likely have been different.

Luny's versions of Trafalgar probably focused more on a clear, detailed, and somewhat documentary representation of the ships and the action. He aimed for accuracy in depicting the specific vessels involved and the tactical situation, appealing to patrons who wanted a recognizable record of the battle. The demand for images of Trafalgar was immense, and Luny's reputation for maritime accuracy made him a natural choice for naval officers and others seeking commemorative paintings of this pivotal moment in British history.

Beyond the Battles: Shipping and Coastal Life

While famous for his battle scenes, Luny's oeuvre encompassed a much wider range of maritime subjects. He frequently painted scenes of everyday shipping, capturing the bustling activity of ports and estuaries. Works like A frigate of the Royal Navy leaving Cork Harbour showcase his skill in depicting specific types of vessels within their natural environment, demonstrating an understanding of wind, tide, and ship handling.

He also turned his attention to less formal aspects of coastal life. Smugglers unloading casks in a rocky Cove entrance reveals an interest in narrative and social observation. This painting captures the clandestine activities of smugglers, figures often romanticized but also part of the harsh economic realities of coastal communities. Such works demonstrate Luny's versatility and his ability to find artistic subjects beyond the grandeur of naval warfare, engaging with the human element of the maritime world.

Capturing the Coast: Landscapes and Ports

Luny was also a capable painter of coastal landscapes and port scenes, where the topography and atmosphere were as important as the vessels depicted. His early work The Prospect of Madeira and Portorosso indicates an early interest in capturing specific locations. Later in his career, particularly after moving from London, landscapes became more prominent.

His painting St Michael’s Mount, Cornwall (1830) is a fine example, depicting the iconic tidal island with sensitivity to light and atmosphere. His relocation to Teignmouth in Devon provided new coastal scenery to explore. These works connect Luny to the broader tradition of British landscape painting, which was flourishing during his lifetime with artists like Richard Wilson and Thomas Gainsborough establishing landscape as a major genre, though Luny always retained his primary focus on the maritime aspect.

Luny's Artistic Style: Realism and Drama

Thomas Luny's style is best characterized as a blend of detailed realism and controlled drama. His primary strength lay in the accurate portrayal of ships. He possessed an exceptional understanding of naval architecture, rigging, and the way vessels behaved under different weather conditions. This technical accuracy lent his work an air of authority and authenticity highly valued by his patrons, many of whom were knowledgeable seamen themselves.

However, Luny was not merely a topographical recorder of ships. He skillfully employed light and shadow (chiaroscuro) to create dramatic effects, particularly in his storm scenes and battle paintings. He could evoke the turbulence of a gale or the smoke-filled chaos of combat. Compared to the sometimes calmer, more decorative styles of earlier marine painters like Peter Monamy or Samuel Scott, Luny infused his work with a greater sense of dynamism and atmospheric presence, bridging the gap between the detailed Dutch-influenced tradition and the emerging Romantic sensibility.

Luny and his Contemporaries: A Crowded Field

Thomas Luny operated within a vibrant and competitive field of marine painters in Britain. His initial mentor, Francis Holman, provided his foundational training. He emerged alongside other notable talents. Dominic Serres the Elder, Marine Painter to King George III, was a dominant figure whose career overlapped with Luny's early years.

Luny faced direct competition from artists like Thomas Whitcombe and John Cleveley the Younger, both highly regarded marine specialists. Nicholas Pocock, a former sea captain, brought his own nautical expertise to his paintings, particularly battle scenes. Robert Dodd also specialized in depicting naval actions with considerable accuracy. William Anderson focused more on coastal and river scenes, often with a calmer mood. Luny had to distinguish himself amidst this talented group, primarily through his prolific output, reliability, and the consistent quality and accuracy of his ship portrayal, combined with his dramatic flair. He also navigated the changing artistic tides that saw the rise of J.M.W. Turner, whose revolutionary approach to light and atmosphere would eventually transform marine painting.

The Move to Teignmouth

Around 1807, Thomas Luny made a significant life change, leaving the bustling metropolis of London and relocating to the coastal town of Teignmouth in Devon. The reasons for this move are not definitively recorded but likely involved several factors. He may have sought a quieter life away from the pressures of the capital, or perhaps the coastal environment of Devon offered fresh artistic inspiration.

It's also highly probable that health reasons played a part. By this time, Luny was approaching fifty, and the move might have been prompted by the early stages of the health problems that would later afflict him. In Teignmouth, he continued to paint actively. His London dealer, Mr. Merle, likely continued to supply him with commissions, particularly for ship portraits requested by merchants and captains based in the West Country ports or connected through the ongoing East India Company network. He also established connections with local patrons, including naval officers residing in the area, such as Captain George Tobin.

Painting Through Adversity: The Later Years

Luny's later life was marked by a significant physical challenge. He developed severe rheumatoid arthritis, a debilitating condition that progressively affected his joints, particularly his hands. For a painter reliant on manual dexterity for detailed work, this must have been a devastating blow. Accounts suggest that by the 1820s, his hands were significantly crippled.

Despite this immense adversity, Luny's determination and passion for painting remained undimmed. He remarkably continued to produce a large volume of work until his death in 1837. It is believed he adapted his technique, perhaps holding the brush between his wrists or using other methods to compensate for the loss of finger mobility. While some critics suggest a decline in the refinement of his later works compared to his peak years, the sheer tenacity and continued productivity in the face of such disability are extraordinary.

Prolific Production and Studio Practice

One of the most astonishing aspects of Thomas Luny's career is his immense output. It is estimated that he produced over 2,200 paintings, and possibly as many as 3,000, during his lifetime. This level of productivity is remarkable, especially considering the detailed nature of many of his works and his later physical limitations.

This raises questions about his studio practice. While direct evidence is scarce, it's plausible that, like many successful artists of the period, Luny may have employed studio assistants, particularly during his peak London years, to help with preparatory work, backgrounds, or perhaps creating copies or versions of popular compositions. However, the consistent style across much of his work suggests he maintained close control. His prolific nature undoubtedly contributed to his widespread popularity and the relatively large number of his paintings that survive today, offering a broad representation of his skills and subjects.

Legacy and Collections

Thomas Luny died in Teignmouth in 1837, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant legacy. He is firmly established as a leading figure in the "third generation" of British marine painters, following the pioneers like Peter Monamy and Samuel Scott, and the generation of Dominic Serres and his own master, Francis Holman. His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent marine artists who continued the tradition of accurate ship portrayal combined with atmospheric effects, such as Clarkson Stanfield and George Chambers Sr.

Today, Luny's paintings are held in high regard and are represented in major public collections worldwide, particularly those specializing in maritime history and art. Key institutions include the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, London; the Royal Albert Memorial Museum in Exeter (which holds a significant collection due to his Devon connection); and The Mariners' Museum and Park in Newport News, Virginia. His works are valued not only for their artistic merit but also as important historical documents, providing visual evidence of ship design, naval tactics, and maritime life during a crucial era of British history.

Enduring Appeal

The enduring appeal of Thomas Luny's work stems from several factors. His technical skill in rendering ships accurately satisfies viewers interested in maritime history and technology. His dramatic compositions, particularly the battle scenes and storm-tossed seas, offer visual excitement and narrative power. His paintings capture the spirit of a nation defined by its relationship with the sea – its naval power, its global trade, and the daily lives of those who worked on or by the water.

Furthermore, the story of his perseverance in later life, continuing to paint despite severe arthritis, adds a compelling human dimension to his artistic legacy. He remains a key figure for understanding the evolution of British marine art, bridging the gap between the more topographical traditions of the earlier eighteenth century and the burgeoning Romanticism of the nineteenth.

Conclusion

Thomas Luny was more than just a painter of ships; he was a visual historian of Britain's maritime age. From his early training under Francis Holman to his prolific output spanning over five decades, he dedicated his art to the sea and its vessels. Whether depicting the intricate details of an East Indiaman, the dramatic fury of a naval battle like the Nile or Trafalgar, or the tranquil beauty of a coastal scene, Luny brought a combination of accuracy, atmospheric sensitivity, and dramatic flair to his subjects. His connections with the Royal Navy and the East India Company provided him with unique insights and patronage, while his move to Devon later in life offered new perspectives. Despite facing significant physical challenges, his unwavering dedication resulted in an astonishing body of work that continues to be admired for its skill, historical value, and evocative portrayal of life at sea. Thomas Luny rightfully holds a prominent and enduring place in the annals of British art history.