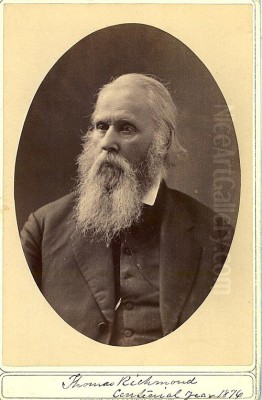

The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Britain witnessed a flourishing of artistic talent, particularly in the realm of portraiture. While grand canvases by masters like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough dominated the Royal Academy exhibitions, a more intimate and personal form of likeness, the portrait miniature, held a special place in the hearts and pockets of the affluent. Among the skilled practitioners of this delicate art was Thomas Richmond, born in 1771 and passing away in 1837. His life and career, though perhaps not as widely celebrated today as some of his bombastic contemporaries, offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic, social, and familial networks of Georgian and early Victorian England.

The Richmond Artistic Lineage

Thomas Richmond (1771-1837) was not an isolated artistic phenomenon but rather a key figure in a notable artistic dynasty. He was the son of Thomas Richmond Snr. (1745–1794), also a painter, though less is documented about the elder Richmond's specific focus or success. It was from his father that young Thomas likely received his initial artistic training and inclination. This familial tradition of artistic pursuit would continue impressively with his own son, George Richmond (1809–1896), who would go on to become a highly successful and esteemed portrait painter, a Royal Academician, and a friend to many of the leading figures of the Victorian era, including William Gladstone and John Ruskin. George's son, in turn, Sir William Blake Richmond (1842–1921), also achieved fame as a painter and designer, particularly known for his classical subjects and mosaic work. Thus, Thomas Richmond (1771-1837) stands as a crucial link, a second-generation artist who nurtured the talents of a third, even more celebrated, generation.

The Art of the Miniature Portrait

To understand Thomas Richmond's contribution, one must appreciate the significance of miniature painting during his lifetime. These small, often oval or rectangular, portraits, typically painted in watercolour on ivory or vellum, were highly prized. They served as intimate keepsakes, tokens of affection, and portable representations of loved ones. In an age before photography, miniatures were the most personal way to carry an image of a spouse, child, or cherished friend. They were often set into lockets, brooches, or small frames, designed to be held in the hand or worn close to the body. The technical skill required was immense, demanding a steady hand, keen eyesight, and the ability to capture a likeness and personality on a diminutive scale. Artists like Richard Cosway, George Engleheart, and Andrew Plimer were among the leading miniaturists of the day, setting a high standard for elegance and refinement.

Thomas Richmond's Career and Style

Thomas Richmond established himself as a respected miniature painter in London. He began exhibiting his works at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1795, a practice he continued with regularity for many years, showcasing his talent to a discerning public and potential patrons. His style was characteristic of the late Georgian period, emphasizing a faithful likeness, delicate execution, and often a subtle idealization of the sitter. He worked primarily in watercolour on ivory, the preferred medium for its luminous quality, which allowed for soft, blended skin tones and intricate detailing in costume and hair.

While specific, universally recognized "masterpieces" by Thomas Richmond (1771-1837) might not be as readily named as those by, for example, Sir Thomas Lawrence or Henry Raeburn in the field of oil portraiture, his body of work consists of numerous high-quality miniatures. These would typically be portraits of gentlemen and ladies of the era, often unnamed in current collections but identifiable by their costume and hairstyle as belonging to the late 18th or early 19th century. His sitters were likely drawn from the gentry, the professional classes, and the burgeoning middle class, who sought these personal mementos. Examples of his work can be found in various museum collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, which holds a significant collection of British miniatures.

His portraits are generally characterized by a sensitive rendering of the face, with careful attention to the eyes, which were considered the window to the soul. The backgrounds are often simple, perhaps a stippled sky effect or a plain wash, ensuring the focus remains entirely on the sitter. The brushwork is fine and controlled, demonstrating the meticulous technique required for this art form. He navigated the stylistic shifts from the more formal Neoclassicism prevalent in his early career towards the burgeoning Romantic sensibilities that valued individual expression and emotion, though miniatures by their nature often retained a degree of polite restraint.

The Artistic Milieu of Georgian London

Thomas Richmond worked during a vibrant period in British art. The Royal Academy, founded in 1768 with Sir Joshua Reynolds as its first president, was the dominant force, shaping taste and providing a crucial platform for artists. Richmond would have been aware of, and likely interacted with, a wide array of fellow artists. In the field of miniature painting, his contemporaries, apart from the aforementioned Cosway, Engleheart, and Plimer, included figures like Samuel Shelley, known for his graceful compositions, and Andrew Robertson, a Scot who brought a certain robustness to the art form. Ozias Humphry was another significant miniaturist, though his eyesight issues later led him to work in pastels.

Beyond miniaturists, the world of larger-scale portraiture was thriving. Sir Thomas Lawrence was the preeminent society portraitist, his dazzling brushwork and ability to capture glamour making him the successor to Reynolds. John Hoppner was a significant rival to Lawrence. Scottish painters like Sir Henry Raeburn brought a distinct, characterful approach to portraiture. In historical and subject painting, artists such as Benjamin West (an American who became President of the Royal Academy after Reynolds), Henry Fuseli with his dramatic and often unsettling visions, and later, David Wilkie, known for his genre scenes, were prominent. The landscape tradition was also evolving, with J.M.W. Turner and John Constable beginning to forge their revolutionary paths. Richmond, while specializing in a distinct field, would have been part of this broader artistic conversation, his works exhibited alongside theirs at the Academy.

Navigating Identity: The Artist and His Namesakes

It is important to acknowledge that the name "Thomas Richmond" was not unique to the artist during this period. Historical records occasionally mention other individuals named Thomas Richmond active in different fields, which can sometimes lead to confusion for researchers. For instance, the provided initial information alluded to a Thomas Richmond involved in mathematical research concerning quasiorders and principal topologies, and another Thomas Richmond credited with medical contributions, such as designing an eye speculum and recording disease patterns in London around 1800.

While these achievements are notable in their respective domains, it is crucial to distinguish these individuals from Thomas Richmond, the miniature painter (1771-1837). The painter's life and work were firmly rooted in the visual arts, his contributions measured by the delicate portraits he created and his role within the London art scene and his own artistic family. The skills and intellectual pursuits of a mathematician or a medical practitioner, while admirable, belong to different spheres of endeavor. The primary historical identity of Thomas Richmond (1771-1837) for art historians is that of a skilled miniaturist. The scarcity of detailed biographical information or personal anecdotes specifically about the painter, as noted in the initial query, sometimes makes it tempting to conflate identities, but careful scholarship requires maintaining these distinctions.

Representative Works and Patronage

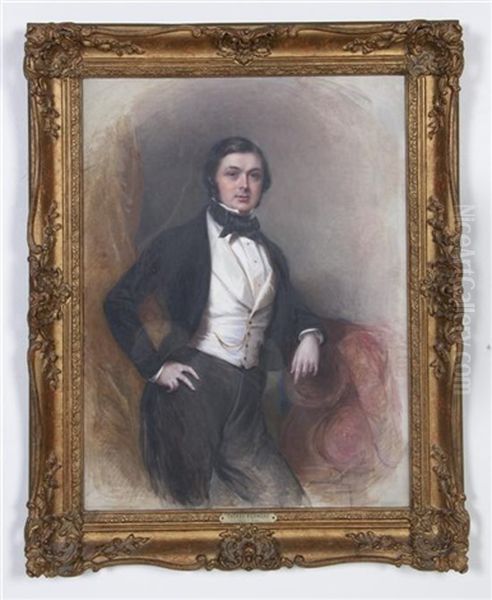

Identifying specific, named "representative works" for Thomas Richmond (1771-1837) that have achieved widespread fame can be challenging, as is often the case with miniaturists whose sitters were not always public figures of the highest echelon. However, his oeuvre would include numerous "Portrait of a Gentleman," "Portrait of a Lady," or "Portrait of an Officer." These titles, common in exhibition catalogues and museum databases, reflect the nature of his commissions.

For example, a typical work might depict a gentleman in the high-collared coat and cravat fashionable in the early 1800s, his expression serious yet amiable. A "Portrait of a Lady" might show her with fashionably styled hair, perhaps adorned with pearls or ribbons, wearing a high-waisted dress of the Regency period. The quality would lie in the lifelike rendering of the features, the subtle modelling of the face, and the delicate handling of hair and fabric. His work would have been sought after by families wishing to commemorate their members, by individuals seeking a memento of a loved one, or by military officers and officials needing a portable likeness.

The patronage for miniaturists like Richmond came from a broad segment of society. While royalty and the highest aristocracy might favor renowned court painters like Cosway, there was a substantial market among the landed gentry, successful merchants, military and naval officers, and professionals. These individuals appreciated the artistry and intimacy of miniatures and could afford the fees of a competent and recognized practitioner like Richmond. His regular exhibition record at the Royal Academy would have served as his primary means of attracting such patrons.

The Decline and Legacy of Miniature Painting

During the later part of Thomas Richmond's career, the art of miniature painting faced new challenges. While it remained popular well into the 1830s and 40s, the advent of photography, particularly the daguerreotype process introduced in 1839 (two years after Richmond's death), began to offer a quicker and often cheaper means of obtaining a personal likeness. Though early photography had its own limitations, its rise signaled a gradual decline in the demand for painted miniatures as the primary form of small-scale portraiture.

Despite this eventual shift, Thomas Richmond's contributions, and those of his contemporaries, remain significant. They captured the likenesses of a generation, providing invaluable historical records of faces, fashions, and social aspirations. His work exemplifies the high level of skill and artistry achieved in British miniature painting. Furthermore, his role as the father and early mentor of George Richmond ensures his place in the narrative of one of Britain's most distinguished artistic families. Artists like Sir William Charles Ross continued the tradition of miniature painting with great success even into the Victorian era, but the landscape was undeniably changing.

Further Considerations on His Art

Richmond's miniatures, like those of his peers, were more than just faces; they were social documents. The choice of attire, the hairstyle, the subtle inclusion of jewelry or insignia—all these elements conveyed information about the sitter's status, profession, and adherence to contemporary fashion. The very act of commissioning a miniature spoke of a certain level of affluence and a desire for personal remembrance.

His technique would have involved meticulous stippling and hatching with fine brushes to build up form and color on the unforgiving surface of ivory. Ivory's natural translucency, when left bare or thinly painted, could impart a luminous glow to the skin tones, a quality highly prized in miniatures. The pigments, mixed with gum arabic as a binder, had to be applied with precision, as mistakes were difficult to correct. The scale itself presented a challenge, requiring artists to condense a personality into a space often no larger than a few inches.

While he may not have been as flamboyant or as intimately connected with the highest echelons of courtly life as Richard Cosway, whose miniatures of the Prince Regent (later George IV) and his circle are iconic, Thomas Richmond represented the solid, skilled professional who catered to a broader, yet still discerning, clientele. His consistent presence at Royal Academy exhibitions for several decades attests to his sustained practice and recognized ability. He was part of a community of artists that included not only miniaturists but also engravers who would translate larger portraits into prints, such as Francesco Bartolozzi or William Ward, further disseminating images to a wider public.

The Context of Artistic Training and Societies

The artistic education of someone like Thomas Richmond would have likely involved apprenticeship, perhaps initially with his father, followed by study at the Royal Academy Schools if he enrolled. The RA Schools offered free instruction to promising students, focusing on drawing from casts of antique sculpture and then from live models. This classical grounding was considered essential for all artists, regardless of their eventual specialization.

Beyond the Royal Academy, other artistic societies were emerging, such as the Associated Artists in Water Colours (founded 1807) and later the Society of Painters in Water Colours (founded 1804, becoming the "Old" Water-Colour Society). While Richmond is primarily known for miniatures on ivory, the broader watercolor movement was gaining strength, with artists like Thomas Girtin and the young J.M.W. Turner revolutionizing landscape painting in that medium. This environment of active artistic production and exhibition provided both competition and stimulus for artists like Richmond.

His son, George Richmond, would benefit from this established artistic world, studying at the Royal Academy Schools and becoming part of "The Ancients," a group of young artists inspired by William Blake, which also included Samuel Palmer and Edward Calvert. The elder Thomas Richmond's career provided a foundation upon which George could build, navigating the changing artistic tastes of the Victorian era.

Concluding Thoughts on Thomas Richmond (1771-1837)

Thomas Richmond occupies a respectable and important place in the history of British miniature painting. Active during its golden age, he produced a significant body of work characterized by skill, sensitivity, and adherence to the refined aesthetics of his time. While not a revolutionary figure, he was a consummate professional who upheld the high standards of his demanding craft. His portraits provided intimate and cherished likenesses for his sitters, capturing a generation of British society on a small, personal scale.

His legacy is twofold: firstly, in the surviving miniatures themselves, which offer glimpses into the past and stand as examples of a highly skilled art form; and secondly, in his role within the Richmond artistic dynasty, as the father of the more famous George Richmond. He represents the dedicated artist who, while perhaps not achieving the highest echelons of fame reserved for a select few like Sir Thomas Lawrence or his contemporary miniaturist Richard Cosway, nevertheless contributed significantly to the rich tapestry of British art during the Georgian and early Regency periods. His career underscores the importance of specialist artists who catered to specific, yet vital, needs within the art market, ensuring that the desire for personal representation was met with elegance and skill. His life and work remind us that the art world is composed not only of its brightest stars but also of the many talented individuals who sustain its traditions and serve its public with dedication.