Thomas Roberts, an artist whose life was tragically cut short, stands as one of the most significant figures in eighteenth-century Irish landscape painting. Born in Waterford in 1749, he emerged during a period of burgeoning national identity and artistic development in Ireland. His work, characterized by a delicate sensibility, refined technique, and a deep appreciation for the natural beauty of the Irish countryside, captured the essence of the picturesque, a prevailing aesthetic ideal of his time. Though his career spanned little more than a decade, Roberts produced a body of work that not only earned him acclaim among his contemporaries but also secured his lasting reputation as a pivotal artist in the history of Irish art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Thomas Roberts was born into a family with strong artistic and architectural connections. His father, John Roberts (c.1712-1796), was a renowned architect in Waterford, responsible for designing both the Protestant and Catholic cathedrals in the city, a testament to his skill and reputation. This environment undoubtedly fostered an early appreciation for art and design in the young Thomas. He also had a younger brother, Thomas Sautelle Roberts (c.1760-1826), who would later follow in his footsteps as a landscape painter, sometimes leading to confusion between their works, though their styles eventually diverged.

To pursue formal artistic training, Thomas Roberts moved to Dublin and enrolled in the Dublin Society's Drawing Schools. These schools, founded to promote improvement in agriculture, arts, and manufactures, played a crucial role in nurturing Irish artistic talent. Here, Roberts likely studied under masters such as James Mannin and Robert West. He honed his skills alongside other aspiring artists, including his known teacher, the landscape painter George Mullins, and possibly John Butts and Jonathan Fisher, who also became notable figures in Irish landscape art. The curriculum would have emphasized drawing from casts, life drawing, and copying from Old Masters, providing a solid foundation in academic principles.

Roberts quickly distinguished himself, winning prizes at the Dublin Society Schools in 1763. This early recognition was indicative of his prodigious talent. His training would have exposed him to the prevailing European artistic conventions, particularly the classical landscape tradition established by artists like Claude Lorrain and Gaspard Dughet, and the more dramatic, untamed visions of Salvator Rosa. These influences would become evident in his mature work, yet Roberts would adapt them to the specific character of the Irish landscape.

The Influence of the Picturesque

The latter half of the eighteenth century saw the rise of the "picturesque" as a dominant aesthetic theory, particularly in Britain and Ireland. Championed by writers like William Gilpin, the picturesque sought a middle ground between the serene beauty of the classical ideal and the awe-inspiring terror of the sublime. It valued variety, irregularity, texture, and a certain rustic charm in landscapes. Scenes that were "fit to be in a picture" were those that offered interesting compositions, contrasting light and shadow, and a sense of harmonious, if untamed, nature.

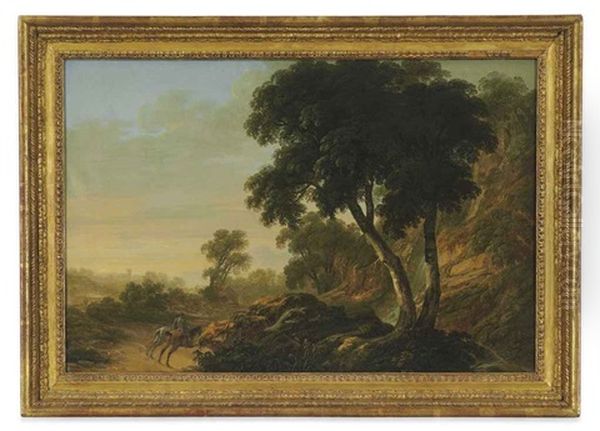

Thomas Roberts's work is deeply imbued with the spirit of the picturesque. He excelled at capturing the nuanced beauty of Irish demesnes, river valleys, and lakes, often framing them with carefully arranged trees and figures that added scale and narrative interest. His landscapes were not mere topographical records; they were carefully composed artistic interpretations designed to evoke a particular mood and aesthetic pleasure. He skillfully balanced the wildness of nature with a sense of order and refinement, appealing to the tastes of his wealthy patrons who were often engaged in "improving" their estates according to picturesque principles.

His handling of light was particularly adept, often suffusing his scenes with a soft, atmospheric glow or using chiaroscuro to create dramatic effect. The foliage in his paintings is rendered with meticulous detail, yet without sacrificing the overall harmony of the composition. Figures, whether they be local peasants, fishermen, or strolling gentry, are integrated seamlessly into the landscape, enhancing its picturesque quality and often providing a subtle social commentary or narrative element.

Major Patrons and Commissions

Like many artists of his era, Thomas Roberts relied on the patronage of the wealthy aristocracy and landed gentry. Ireland in the eighteenth century had a vibrant Ascendancy class, many of whom were keen to commission artworks that celebrated their estates and their sophisticated tastes. Roberts was fortunate to attract several important patrons who provided him with significant commissions.

One of his most important patrons was the Duke of Leinster, for whom he painted a series of views of Carton House in County Kildare, the ducal seat. These paintings, such as "A View of the Lake and Island at Carton, with the Tyrconnell Tower and New Garden Front" (c. 1772), showcase Roberts's ability to depict grand estates with both accuracy and artistic flair, highlighting the improvements made to the landscape and the elegance of the architecture.

Another key patron was Lord Powerscourt, who commissioned views of his magnificent estate at Powerscourt in County Wicklow, renowned for its dramatic waterfall and scenic demesne. Roberts's paintings of Powerscourt, including views of the waterfall, capture the sublime beauty of this location while still adhering to picturesque conventions. He also worked for the Earl of Milltown, painting views of Russborough House, and for Viscount Cremorne (Thomas Dawson), for whom he painted views of his estate at Dawson Grove, County Monaghan, and later, views around his English estate near Chelsea after Cremorne moved to London.

These commissions often involved creating sets of paintings depicting various aspects of an estate, intended to be displayed together. They served not only as works of art but also as status symbols, reflecting the owner's wealth, taste, and connection to the land. Roberts's success in securing such patronage speaks to the high regard in which his work was held. His ability to capture the specific character of these Irish estates, while imbuing them with a timeless, picturesque quality, made him highly sought after.

Representative Works

Thomas Roberts's oeuvre, though limited by his short life, contains several masterpieces that exemplify his style and skill.

"A View of the Upper Lake, Killarney" (c. 1770s) is a fine example of his ability to capture the wilder aspects of the Irish landscape. The rugged mountains and serene waters of Killarney are rendered with a sensitivity to atmosphere and light, creating a scene that is both majestic and tranquil. The inclusion of small figures in a boat adds a sense of scale and human presence to the vastness of nature.

"A View of the Salmon Leap at Leixlip, Co. Kildare" (c. 1772) is another iconic work. This painting depicts a well-known beauty spot on the River Liffey, famous for its waterfall where salmon were observed leaping. Roberts captures the dynamic energy of the cascading water and the lushness of the surrounding foliage. The composition is carefully balanced, with figures fishing and observing the scene, adding to its picturesque charm. This work, like many of his others, demonstrates his mastery in rendering water, rocks, and trees with convincing texture and detail.

His series of paintings for Carton House, such as "A View of the Park at Carton from the East" and "A View of the Lake at Carton," are exemplary of his estate portraiture. These works not only document the appearance of the estate but also convey a sense of its idyllic and well-ordered nature, reflecting the pride and status of its owner, the Duke of Leinster. The careful arrangement of trees, the gentle undulation of the land, and the play of light and shadow all contribute to a harmonious and pleasing effect.

"A View of Beauparc, Co. Meath, on the River Boyne" (c. 1771) is another significant work, showcasing a tranquil river scene with classical undertones. The calm waters reflect the sky and surrounding trees, creating a serene and contemplative mood. The composition, with its framing trees and distant vista, recalls the work of Claude Lorrain, yet the specific details of the Irish landscape give it a distinct local character.

Other notable works include views of Lucan House and its demesne, and landscapes around Bellisle, County Fermanagh. Each of these paintings demonstrates Roberts's consistent quality, his refined palette, and his ability to evoke the unique atmosphere of the Irish countryside. His attention to detail, particularly in the rendering of foliage and the subtle gradations of light, set him apart from many of his contemporaries.

Contemporaries and the Irish Art Scene

Thomas Roberts worked within a burgeoning Irish art scene. While Dublin did not possess the same artistic infrastructure as London, it was a vibrant cultural center. The Dublin Society's Schools were instrumental in training artists, and institutions like the Royal Dublin Society provided exhibition opportunities.

Among his direct contemporaries in landscape painting was William Ashford (c.1746-1824), who became one of the leading landscape artists in Ireland, eventually becoming the first President of the Royal Hibernian Academy. Ashford's style, while also picturesque, often had a broader, more expansive quality compared to Roberts's more intimate and detailed approach. George Barret Sr. (c.1732-1784) was another major Irish landscape painter, though he left Ireland for London in 1762, before Roberts's career fully blossomed. Barret's success in London, however, helped to raise the profile of Irish landscape painting.

Jonathan Fisher (fl. c.1763-1809), possibly a fellow student or even a teacher of Roberts, was known for his topographical views and aquatints of Irish scenery, particularly Killarney. His work, while perhaps less painterly than Roberts's, contributed significantly to the visual documentation of Ireland. Thomas Sautelle Roberts, Thomas's younger brother, also became a respected landscape painter, continuing the family tradition after Thomas's death. His style, however, evolved towards a more Romantic sensibility, influenced by later trends.

Other artists active in Ireland during this period included portrait painters like Hugh Douglas Hamilton and Robert Hunter, and subject painters. The overall artistic environment was one of growing confidence and a desire to develop a distinctly Irish school of art, even as artists continued to look to European models for inspiration. Roberts's work can be seen as a key contribution to this development, demonstrating that Irish landscape could be a subject of high art, treated with the same sophistication and skill as the landscapes of Italy or England. His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent Irish landscape painters who continued to explore the picturesque and Romantic potential of the Irish countryside. The English landscape tradition, with figures like Richard Wilson, Thomas Gainsborough (who also painted landscapes), and Paul Sandby, provided a broader context and often a point of comparison or influence for Irish artists.

Later Years and Premature Death

Despite his success and growing reputation in Ireland, Thomas Roberts's health began to decline. He suffered from consumption (tuberculosis), a common and often fatal illness in the eighteenth century. In search of a more favorable climate, he traveled to Lisbon, Portugal, in late 1777 or early 1778. Lisbon, with its milder winters, was a popular destination for those suffering from respiratory ailments.

Unfortunately, the change of climate did not bring about a recovery. Thomas Roberts died in Lisbon in March 1778, at the tragically young age of 29. His promising career was cut short just as he was reaching his artistic maturity. It is tantalizing to speculate on how his style might have evolved had he lived longer, and what further contributions he might have made to Irish art. His death was a significant loss to the Irish art world.

Some of his unfinished works and studio contents were inherited by his brother, Thomas Sautelle Roberts, who completed some of his paintings. This has occasionally led to complexities in attribution, but the distinct qualities of Thomas Roberts's hand are generally recognizable.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Thomas Roberts is widely regarded as one of Ireland's finest landscape painters of the eighteenth century. Despite the brevity of his career, he produced a body of work that is remarkable for its quality, sensitivity, and technical refinement. He successfully adapted the conventions of European classical and picturesque landscape painting to the specific character of the Irish scene, creating images that were both aesthetically pleasing and evocative of place.

His work represents a high point in Irish picturesque painting. He captured the beauty of Irish demesnes, rivers, and lakes with an intimacy and delicacy that few of his contemporaries matched. His paintings provide valuable visual records of eighteenth-century Irish estates and landscapes, but more importantly, they are works of art that continue to delight and impress viewers with their skillful composition, subtle use of color, and atmospheric effects.

Art historians recognize Roberts as a key figure in the development of a native Irish school of landscape painting. He demonstrated that Irish scenery was a worthy subject for serious artistic treatment, and his work helped to foster a greater appreciation for the natural beauty of the country. His influence can be seen in the work of later Irish landscape painters, and his paintings are now prized possessions in major Irish public collections, including the National Gallery of Ireland, and in private collections.

The art critic Anne Crookshank, a leading authority on Irish art, has praised Roberts for his "exquisite delicacy" and his ability to capture the "gentle, lyrical beauty" of the Irish landscape. His paintings are seen as embodying a particular moment in Irish cultural history, reflecting the tastes and aspirations of the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy, but also transcending their specific historical context to achieve a timeless appeal. While artists like James Arthur O'Connor and later Paul Henry would explore different, often more rugged or melancholic, aspects of the Irish landscape, Roberts established a benchmark for refined picturesque representation.

Conclusion

Thomas Roberts's premature death was a profound loss, yet the legacy he left through his art is enduring. In a career that spanned barely a decade, he established himself as a master of the picturesque landscape, capturing the nuanced beauty of Ireland with a rare sensitivity and skill. His paintings of Carton, Powerscourt, Leixlip, and other iconic Irish locations remain as testaments to his talent and as cherished representations of Ireland's natural and cultivated heritage. As an art historian, one can only admire the delicate precision, the harmonious compositions, and the evocative atmospheres he created. Thomas Roberts rightfully holds a distinguished place in the canon of Irish art, a painter whose work continues to resonate with its quiet beauty and artistic integrity. His contribution was vital in shaping the course of landscape painting in Ireland, paving the way for future generations of artists to explore the rich and varied scenery of their homeland.