Viviano Codazzi stands as a significant figure in the landscape of Italian Baroque painting, renowned primarily for his specialized focus on architectural scenes, known as vedute, and imaginative architectural fantasies, or capricci. Active during the vibrant and transformative 17th century, Codazzi carved a unique niche for himself, blending meticulous depictions of structures with atmospheric settings and often collaborating with figure painters to populate his grand stages. His work offers a fascinating window into the period's fascination with classical antiquity, urban environments, and the dramatic potential of perspective.

Origins and Early Development

Viviano Codazzi was born around 1604 in Bergamo, a city in the Lombardy region of northern Italy, which had its own artistic traditions. While details of his earliest training remain somewhat obscure, art historians suggest that he likely received formative instruction in Rome before establishing his career further south. Rome, during the early 17th century, was the undisputed center of the art world, buzzing with the energy of the early Baroque, pioneered by artists like Caravaggio and Annibale Carracci, and attracting talent from across Europe.

If Codazzi did train in Rome during the 1620s or early 1630s, he would have been exposed to a rich tapestry of influences. One significant figure often cited as an influence, particularly if Codazzi spent time in Rome early on, is Agostino Tassi. Tassi was a master of quadratura, the illusionistic painting of architecture on ceilings and walls, and also a landscape painter. His expertise in perspective and architectural rendering could well have provided a model or inspiration for the young Codazzi's burgeoning interest in architectural subjects.

Furthermore, Rome was becoming a hub for Northern European artists, particularly those from the Netherlands and Flanders. Among these was Pieter van Laer, nicknamed "Il Bamboccio" (meaning "ugly doll" or "puppet"), who arrived in Rome around 1625. Van Laer specialized in small-scale paintings depicting the everyday life of ordinary Romans – peasants, artisans, street vendors – often set against recognizable urban backdrops or rural landscapes. His followers became known as the Bamboccianti. Codazzi is often associated with this circle, not necessarily because he painted the same low-life subjects, but because he shared their interest in realistic depictions of environments and sometimes incorporated similar small, lively figures (often painted by collaborators) into his architectural settings.

The Neapolitan Chapter

Around 1633 or 1634, Viviano Codazzi arrived in Naples. This bustling port city, then under Spanish rule, was another major artistic center, second only to Rome in Italy. It possessed a distinct artistic identity, characterized by a dramatic naturalism often infused with tenebrism, largely influenced by the earlier presence of Caravaggio and the ongoing work of painters like Jusepe de Ribera. Codazzi's arrival coincided with a period of intense artistic activity and patronage.

In Naples, Codazzi solidified his reputation as a specialist in architectural painting. His works from this period often depict recognizable classical structures or idealized architectural compositions rendered with a remarkable command of linear perspective. He demonstrated a profound understanding of architectural forms, proportions, and the play of light and shadow across surfaces, lending his scenes a convincing sense of depth and spatial coherence.

It was during his Neapolitan years that Codazzi engaged in significant collaborations. One of the most notable was with Domenico Gargiulo, better known by his nickname Micco Spadaro. Gargiulo was a Neapolitan painter known for his lively narrative scenes, landscapes, and depictions of contemporary events, often filled with numerous small figures. Together, Codazzi and Gargiulo worked on prestigious commissions. Among the most important was a series of large canvases depicting scenes from ancient Roman history and landscapes for the Buen Retiro Palace in Madrid, a major project orchestrated by the Spanish Viceroy in Naples. In these works, Codazzi typically provided the expansive architectural settings, while Gargiulo added the narrative figures, creating grand, theatrical compositions.

Codazzi also collaborated with the renowned female painter Artemisia Gentileschi during her time in Naples. Gentileschi, celebrated for her powerful biblical and historical narratives, occasionally worked with specialists for backgrounds or specific elements. Their collaboration is documented, including a painting of Bathsheba, where Codazzi likely contributed the architectural backdrop, demonstrating the interconnectedness of artists with different specializations in the Neapolitan art scene. Other prominent artists active in Naples during this time, such as Massimo Stanzione, further contributed to the city's rich artistic milieu, though direct collaborations with Codazzi are less documented.

Return to Rome and Mature Career

Codazzi's successful Neapolitan period was interrupted by political turmoil. In 1647, Naples erupted in a popular revolt led by Masaniello against Spanish rule. The ensuing instability and violence prompted Codazzi, like some other artists, to seek refuge elsewhere. He fled Naples and settled in Rome, the city where he may have received his initial training. He would remain in Rome for the rest of his life, until his death in 1670.

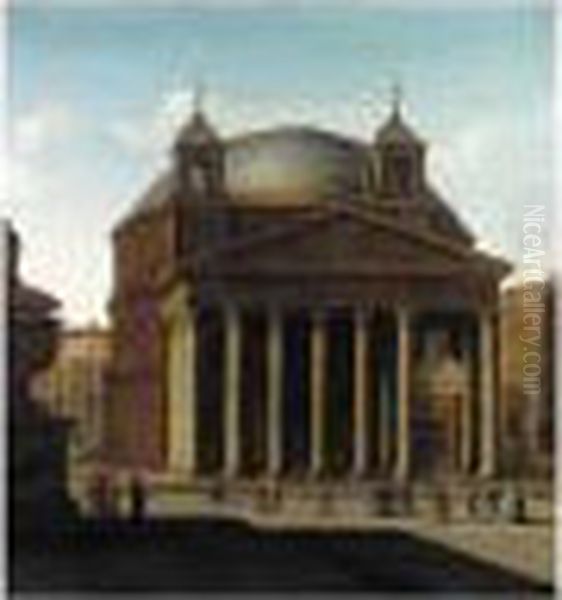

Rome in the mid-17th century was dominated by the High Baroque splendors of Gian Lorenzo Bernini and Francesco Borromini in architecture and sculpture, and painters like Pietro da Cortona. Codazzi continued to develop his specialized genre, finding patrons who appreciated his unique skills. His Roman works often feature views of the city's ancient monuments, such as the Colosseum, the Pantheon, Trajan's Column, and various arches and temple ruins. These were not always strictly accurate topographical representations (vedute precise) but often fell into the category of capricci.

The capriccio, or architectural fantasy, was a genre gaining popularity, allowing artists to combine real structures in imaginative ways, juxtapose ruins with contemporary life, or invent entirely fantastical buildings. Codazzi excelled in this, creating evocative scenes that conveyed the grandeur and decay of ancient Rome. His paintings often possess a serene, sometimes melancholic atmosphere, achieved through careful composition, controlled lighting, and a relatively muted palette compared to the more exuberant High Baroque decorators.

In Rome, Codazzi entered into another significant and long-lasting collaboration, this time with the painter Michelangelo Cerquozzi. Cerquozzi, another artist associated with the Bamboccianti, specialized in genre scenes similar to those of Pieter van Laer, often featuring lively street scenes, markets, or military encampments. From Codazzi's arrival in Rome until Cerquozzi's death in 1657, the two artists frequently worked together. Cerquozzi provided the animated figures – soldiers, travelers, common folk – that populated Codazzi's meticulously rendered architectural perspectives and ruin landscapes. This partnership allowed both artists to play to their strengths, creating integrated compositions that were highly sought after. Other Bamboccianti active in Rome during this period included Jan Miel and Johannes Lingelbach, contributing to the popularity of genre elements within larger compositions.

Artistic Style: Vedute, Capricci, and Ruins

Viviano Codazzi's artistic identity is inextricably linked to architectural painting. He was a master of the veduta, or view painting, though his approach often leaned towards the veduta ideata (idealized view) or the capriccio rather than strict topographical accuracy. His primary interest lay in the architecture itself – its structure, volume, texture, and its placement within a convincing spatial environment.

Linear perspective was fundamental to his art. Codazzi employed perspective grids and vanishing points with great skill to create illusions of deep, receding space. Arches open onto distant vistas, colonnades stretch into the background, and buildings are rendered with geometric precision. This technical mastery gave his works a sense of order and rationality, even when depicting ruins or fantastical combinations of structures.

His treatment of light and shadow is also characteristic. While not employing the dramatic tenebrism of Caravaggio, Codazzi used light effectively to model architectural forms, define space, and create atmosphere. Sunlight often illuminates specific areas, casting long shadows and highlighting the textures of stone, brick, and crumbling plaster. This careful handling of light contributes to the often calm, contemplative mood of his paintings.

The depiction of ruins was a recurring theme, particularly in his Roman period. Paintings like Roman Ruins or views incorporating the Colosseum capture the romantic fascination with the remnants of classical antiquity that was prevalent in the Baroque era. Codazzi rendered these ruins with attention to detail, showing crumbling walls, overgrown vegetation, and the effects of time, but he generally avoided overly dramatic or sentimental representations. Instead, the ruins often serve as majestic backdrops for contemporary life or as elements within a larger, idealized landscape composition. Works like Arsenal at Civitavecchia show his ability to depict more functional, contemporary structures as well, albeit often imbued with a similar sense of grandeur.

Codazzi's style represents a unique blend of realism and imagination. The architectural elements are rendered with convincing detail and structural logic, grounding the scenes in reality. However, the compositions are often idealized or fantastical, combining elements from different locations or periods, reflecting the creative freedom afforded by the capriccio genre. This balance distinguishes his work from purely documentary view painters and from artists whose fantasies were more overtly theatrical or surreal.

Influences Received and Given

Codazzi's art was shaped by several key influences. As mentioned, Agostino Tassi's work in quadratura and perspective likely played a role, especially if Codazzi trained in Rome. The realism and focus on environment found in the work of Pieter van Laer and the Bamboccianti were also significant, particularly evident in the way small figures often inhabit his scenes (even if painted by others) and the attention to everyday textures and details within the grand settings.

He was also aware of developments in landscape painting. The idealized, classically inspired landscapes of French artists working in Rome, such as Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin, and other Northern artists like Herman van Swanevelt, resonated with Codazzi's interest in structured compositions and atmospheric light. While Codazzi focused on architecture, the way he integrated buildings into landscape settings sometimes echoes the compositional strategies and lighting effects found in the works of these masters.

Codazzi, in turn, exerted his own influence. His specialization in architectural painting helped to elevate the genre. His most direct artistic heir was his son, Niccolò Codazzi (1642-1693). Niccolò trained with his father and largely continued his style, becoming a successful architectural painter in his own right. Niccolò worked not only in Italy but also spent considerable time in France, particularly in Paris and Aix-en-Provence, where he collaborated with French artists and contributed to the dissemination of the Italianate architectural painting style abroad.

While direct lines of influence can be hard to trace definitively, Codazzi's work, along with that of other vedutisti and capriccio painters like Giovanni Ghisolfi, contributed to a growing taste for architectural subjects. This trend would culminate in the 18th century with the celebrated Venetian view painters like Canaletto, Bernardo Bellotto, and Francesco Guardi, and the dramatic architectural fantasies of Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Although their styles differed, the groundwork laid by 17th-century specialists like Codazzi was crucial. Some art historians also suggest that later artists, including the great Venetian decorator Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, may have looked to the compositional structures and spatial illusions found in the works of painters like Codazzi when creating their own architectural settings and capricci.

Notable Works

Several paintings stand out as representative of Viviano Codazzi's oeuvre:

Architectural Capriccio with Figures: Many works bear titles like this, highlighting his focus. These typically feature imagined combinations of classical arches, colonnades, and ruins, populated by small figures often painted by collaborators like Cerquozzi or Gargiulo. They showcase his mastery of perspective and atmospheric lighting.

View of the Roman Forum or Roman Ruins: Codazzi painted numerous scenes inspired by the ruins of ancient Rome. These works capture the scale and former magnificence of structures like the Basilica of Maxentius or temples within the Forum, often juxtaposing them with contemporary figures, emphasizing the passage of time.

The Colosseum, Rome: A recurring subject, Codazzi depicted the iconic amphitheater from various viewpoints, sometimes focusing on its imposing structure and sometimes incorporating it into a wider capriccio landscape. These works demonstrate his ability to render complex curved forms and textures accurately.

St. Peter's Basilica: Views featuring St. Peter's, often depicted during its construction or shortly after completion, showcase his skill in rendering monumental contemporary architecture as well as ancient ruins.

Paintings for the Buen Retiro Palace (with Gargiulo): Although dispersed, these large canvases (e.g., Roman Gladiators, Roman Naumachia) represent a major commission and highlight his successful collaboration in creating grand historical-architectural scenes for royal patronage.

Arsenal at Civitavecchia: This work shows his capacity to depict more functional, less idealized architecture, focusing on the structure and activity of the papal port's arsenal.

These examples illustrate the range of Codazzi's work, from relatively accurate views to imaginative fantasies, all unified by his consistent focus on architectural form and space.

Legacy and Conclusion

Viviano Codazzi occupies an important place in the history of Italian Baroque art as a leading specialist in architectural painting. While perhaps overshadowed in his time by artists working in more traditionally prestigious genres like history painting, his dedication to vedute and capricci contributed significantly to the development and popularization of these forms. His technical proficiency in perspective and his ability to create convincing, atmospheric architectural spaces were widely admired.

His collaborations with prominent figure painters like Domenico Gargiulo, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Michelangelo Cerquozzi underscore the collaborative nature of art production in the 17th century and highlight Codazzi's respected position within the artistic communities of Naples and Rome. His influence extended through his son, Niccolò, and contributed to the broader European fascination with architectural views and fantasies that flourished in the following century.

Initially, like many specialists, his work might have been somewhat overlooked by later art historical narratives focused on grand narrative painters. However, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized the importance and quality of his output. Viviano Codazzi is now appreciated for his unique blend of realism and imagination, his technical mastery, and his evocative depictions of architectural grandeur, both real and imagined. His paintings remain compelling testaments to the enduring allure of architecture as an artistic subject and offer a distinct perspective on the visual culture of the Baroque era.