Walter Frederick Osborne stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of late nineteenth-century Irish art. An artist whose life was tragically cut short, Osborne navigated the complex currents of European art, absorbing influences from Realism, Naturalism, and Impressionism, yet forging a path distinctly his own. Primarily celebrated as both a landscape and portrait painter, his enduring legacy rests significantly on his sensitive and insightful depictions of everyday life in Ireland, particularly the experiences of the working class, women, and children in both urban and rural settings. His work offers a valuable window into the social fabric of Ireland during a period of subtle but significant change.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Dublin

Walter Frederick Osborne was born on June 17, 1859, in Rathmines, a suburb of Dublin. Artistry was in his blood; he was the third child of William Osborne, a respected animal painter in his own right, and Anne Jane Woods. Growing up in an artistic household undoubtedly provided early exposure and encouragement. His formal training began in 1876 when he enrolled in the schools of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) in Dublin. The RHA was the principal institution for academic art training in Ireland at the time, providing a solid foundation in drawing and painting according to established conventions.

Osborne quickly distinguished himself as a promising student. In 1877, just a year after enrolling, he won a silver medal, signaling his burgeoning talent. His early promise was further confirmed by prestigious awards. In both 1881 and 1882, he secured the Taylor Art Scholarship, a significant prize awarded by the Royal Dublin Society, which provided funds often used for further study abroad. Perhaps even more indicative of his early direction was winning the Albert Prize in 1880 for his painting Glade in the Phoenix Park. This early landscape work hinted at the sensitivity to nature that would become a hallmark of his later career, even as he was still operating within a broadly academic framework. The Dublin art scene, while perhaps provincial compared to London or Paris, included established figures like the portraitists John Butler Yeats and Sarah Purser, creating a local context for the young artist's development.

Continental Training: Antwerp and the Influence of Masters

Armed with talent and the support of awards like the Taylor Scholarship, Osborne sought to broaden his artistic horizons through study on the European continent, a common path for ambitious young artists of his generation. From 1881 to 1883, he studied at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. Antwerp, with its rich artistic heritage, offered a different environment from Dublin. The academy provided rigorous training, and the city itself was steeped in the legacy of Old Masters, particularly the Flemish Baroque giant, Peter Paul Rubens. Exposure to Rubens' dynamic compositions, rich colour, and vigorous brushwork, even if not directly imitated, would have formed part of the artistic atmosphere Osborne absorbed.

During his time in Antwerp, Osborne was not working in isolation. The city attracted artists from various countries. While direct, significant interaction is not documented, it's noteworthy that Vincent van Gogh also studied briefly at the Antwerp Academy a few years after Osborne, highlighting the city's role as an artistic hub. More immediately impactful on Osborne's developing style, however, were contemporary influences, particularly from France, which were filtering through European art centres.

Travels in France and Brittany: Embracing Naturalism and Impressionism

Following his studies in Antwerp, Osborne embarked on travels between 1883 and 1884, spending significant time in France, particularly in the artistically fertile region of Brittany. This period proved crucial in shaping his mature style. He came under the powerful spell of French Naturalism, a movement that emphasized realistic depictions of rural life and landscape, often imbued with a sense of objective observation yet sympathetic portrayal. The leading figure of this movement, Jules Bastien-Lepage, became a particularly strong influence on Osborne, as he was for many artists across Europe and Britain during the 1880s. Bastien-Lepage's meticulous detail combined with a brighter palette and often poignant subject matter resonated deeply with Osborne.

Simultaneously, Osborne was exposed to the burgeoning influence of Impressionism. While perhaps not adopting its tenets wholesale initially, the Impressionist emphasis on capturing fleeting effects of light and atmosphere, using broken brushwork, and painting en plein air (outdoors) began to permeate his work. He likely encountered the works of key French Impressionists like Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, whose revolutionary approaches to colour and light were transforming landscape painting. Osborne, along with other Irish artists like Roderic O'Conor who also spent considerable time working in France and Brittany, began to integrate these modern French ideas into their practice, adapting them to their own sensibilities and subject matter. This period saw him painting directly from nature, absorbing the light and colours of the French countryside.

Return to Ireland: Forging a Personal Style

Osborne returned to Ireland around 1884, though he continued to travel and paint frequently in England and occasionally revisited Brittany throughout the following decade. His experiences on the continent had irrevocably shifted his artistic perspective. While maintaining a strong foundation in drawing and realistic observation, his palette lightened considerably, his brushwork became looser and more expressive, and his interest in capturing the nuances of light and atmosphere intensified. He began applying the principles learned abroad to Irish subjects, finding inspiration in the landscapes and daily life around him.

His time spent painting in English villages like Walberswick in Suffolk and Rye in Sussex further exposed him to artists exploring similar interests. British painters associated with movements like the Newlyn School in Cornwall, such as Stanhope Forbes and George Clausen, were also grappling with the influence of French Naturalism and Impressionism, focusing on realistic depictions of rural labour and coastal life, often with an emphasis on specific light conditions. Osborne's engagement with these artistic communities, sharing similar concerns, helped solidify his move towards a more modern, light-filled realism.

A key work reflecting his time in Brittany and the influence of Bastien-Lepage is Apple Gathering, Quimperlé (1887). This painting depicts figures in an orchard, rendered with careful attention to detail but also bathed in a soft, natural light. The composition and the sympathetic portrayal of rural activity clearly show the impact of French Naturalism, while the handling of light hints at his growing engagement with Impressionist concerns. It represents a significant step away from his earlier, more academic style towards the mature approach that would define his career.

Documenting Irish Life: Empathy and Observation

Perhaps Walter Osborne's most significant contribution lies in his sensitive and unsentimental depictions of ordinary Irish life, particularly the lives of the less privileged. Throughout the late 1880s and 1890s, he turned his attention increasingly to the streets of Dublin and the rural poor. His canvases capture women tending market stalls, children playing in laneways, elderly people finding moments of rest, and the general ebb and flow of urban and village existence. These were not romanticized visions but rather keenly observed moments rendered with profound empathy.

His subjects often included women, children, the elderly, and the poor – figures frequently overlooked in grander artistic narratives. He painted scenes in St. Patrick's Close, Dublin fish markets, and quiet domestic interiors. Unlike some social realists who might emphasize hardship with overt political commentary, Osborne's approach was generally more observational, allowing the dignity and resilience of his subjects to speak for themselves. His focus on capturing the specific character of Dublin's streets and inhabitants provides an invaluable visual record of the city at the turn of the century.

Works like Life in the Streets: Musicians (also known as A Dublin Street Scene with Musicians) or scenes depicting children playing marbles capture the texture of urban life. His portrayal is direct and honest, avoiding overt sentimentality while still conveying a sense of connection to the people he painted. This focus on contemporary urban reality aligns him broadly with aspects of Impressionism, particularly the work of artists like Edgar Degas who chronicled modern Parisian life, though Osborne's style and emotional tone remained distinctively his own.

The Rural Poor and Social Commentary

Osborne's engagement with the lives of the poor extended beyond the city into the Irish countryside. His travels, particularly in the west of Ireland, brought him into contact with rural poverty, which he depicted with the same honesty and empathy seen in his urban scenes. A poignant example is Galway Cottage (also known as An Old Woman Reading by a Cottage Fire) from 1893. This work shows an elderly couple inside a sparsely furnished cottage, finding warmth by the hearth. The dim lighting, the simple setting, and the quiet dignity of the figures convey the hardships of rural life without resorting to melodrama.

These works carry an implicit social commentary. By choosing to represent the lives of the poor and the elderly with sensitivity and respect, Osborne highlighted their existence within Irish society. While not overtly political, the realism of these depictions subtly challenged viewers to acknowledge the conditions faced by many of their contemporaries. His approach contrasted with the often more idealized or picturesque views of Irish peasant life found in some earlier art. He presented reality as he observed it, filtered through his artistic sensibility.

Master of Landscape: Light, Atmosphere, and Technique

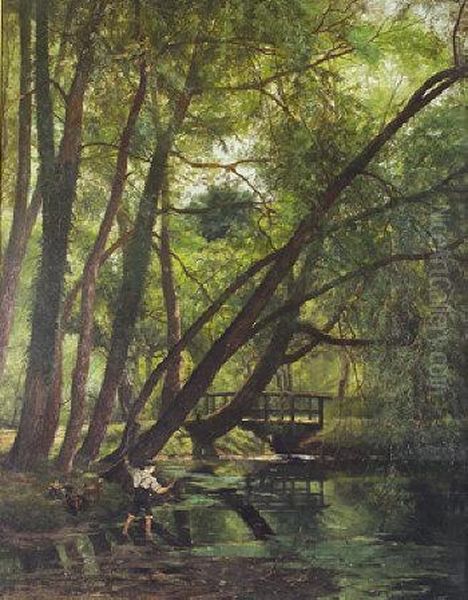

Alongside his genre scenes and portraits, Osborne remained a dedicated landscape painter throughout his career. His early work, like Glade in the Phoenix Park, showed his affinity for nature. His experiences in France and England further honed his skills in capturing the effects of light and atmosphere en plein air. He painted landscapes in various locations across Ireland, England, and Brittany, adapting his technique to the specific conditions he encountered.

His landscape style evolved significantly under the influence of Impressionism. He employed looser, more broken brushwork to convey the shimmer of light on water, the texture of foliage, or the haze of a distant view. His palette became brighter and more attuned to the subtle shifts in colour caused by changing light. He often favoured low viewpoints, which could lend intimacy or grandeur to a scene, and frequently employed warm colour harmonies, particularly in his depictions of evening or morning light.

Osborne experimented with different techniques to achieve desired effects. He sometimes used a "wet-on-wet" approach, applying layers of wet paint over previous wet layers, which allowed for soft blending and subtle tonal transitions, particularly effective in rendering skies and water. His dedication to capturing the specific mood and character of a place, whether a bustling Dublin park, a quiet English estuary, or a rugged stretch of the Irish coast, marks him as one of Ireland's finest landscape painters of the era. His contemporary, Nathaniel Hone the Younger, was another significant Irish landscape painter, but Osborne's style often incorporated more figurative elements and a stronger sense of narrative or human presence within the landscape.

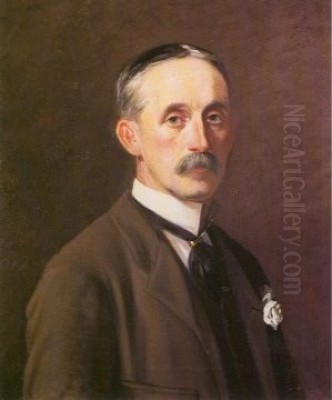

Success as a Portraitist

While Osborne is highly regarded for his genre scenes and landscapes, portraiture formed a significant part of his output and was a crucial source of income, particularly in his later years. By the late 1890s, he had established himself as one of Dublin's leading society portrait painters. He received numerous commissions from prominent families, capturing the likenesses of men, women, and children with skill and sensitivity.

His portraits, while fulfilling the requirements of commissioned work, often retained the freshness and immediacy characteristic of his other paintings. He had a talent for capturing not just a physical likeness but also a sense of the sitter's personality. Examples include his portraits of figures like Mrs. Noel and her daughter Abercrombie, which demonstrate his ability to handle formal compositions while maintaining a lively touch. His approach to portraiture was generally less flamboyant than that of international stars like John Singer Sargent, but shared a concern for capturing character through pose, expression, and the handling of light and texture.

His success in this field placed him in the company of other established Dublin portraitists like Sarah Purser and Sir John Lavery (though Lavery was increasingly based in London). While Lavery also documented society, Osborne's portraits often possess a quieter intimacy. This aspect of his career highlights his versatility and his ability to adapt his skills to different artistic demands, moving comfortably between intimate genre scenes, atmospheric landscapes, and formal portrait commissions.

Artistic Techniques and Media: Versatility and Skill

Walter Osborne was a versatile artist proficient in several media. While many of his most famous works are oil paintings, he was also an accomplished watercolourist and a superb draughtsman. His watercolours often possess a particular luminosity and transparency, well-suited to capturing fleeting effects of light and weather. They demonstrate a fluid handling of the medium and a keen sense of colour harmony.

His pencil sketches are particularly revealing of his working process. He used drawing extensively, not just for preliminary studies but as a way of thinking through compositions and observing details. Numerous sketches survive, showing his careful attention to form, structure, and the arrangement of elements within a scene. For example, preparatory sketches exist for works like Seated Boy and Sea, illustrating how he worked out the low viewpoint and the placement of the figure against the vast expanse of the sea and sky. An 1887 pencil sketch study of ducks on a beach further demonstrates his commitment to observing nature closely and using drawing to refine his compositions before committing them to paint. This strong foundation in drawing underpinned all aspects of his work, providing structure even within his most Impressionistic paintings.

Context, Contemporaries, and Influence

Osborne worked during a dynamic period in European art. He absorbed and responded to major movements like Realism (epitomized by Gustave Courbet), Naturalism (led by Bastien-Lepage), and Impressionism (Monet, Renoir, Degas). His training in Antwerp connected him to the legacy of Flemish masters like Rubens. His travels brought him into contact with artistic currents in France and Britain, where artists like Stanhope Forbes and George Clausen were exploring similar themes of rural life and light.

Within Ireland, he was a leading figure of his generation. He navigated the Dublin art world alongside contemporaries like the landscape painter Nathaniel Hone the Younger and portraitists John Butler Yeats and Sarah Purser. His relationship with Sir John Lavery is interesting; both were successful Irish artists documenting aspects of contemporary life, though often with different focuses and styles. Osborne's commitment to depicting the everyday lives of ordinary Irish people, particularly the poor, gave his work a distinct social dimension. While influenced by international trends, he successfully adapted these influences to create art that was deeply rooted in his Irish context. His work, in turn, would influence subsequent generations of Irish painters drawn to realism and the depiction of local life.

Untimely Death and Lasting Legacy

Tragically, Walter Frederick Osborne's promising career was cut short. He contracted pneumonia and died on April 24, 1903, at the young age of 43. His death was considered a significant loss to the Irish art world. He was at the height of his powers, successfully balancing commissioned portraiture with his more personal explorations of landscape and genre subjects. There is a sense that he had much more potential yet to be fulfilled.

Despite his relatively short life, Osborne left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be highly regarded. He is recognized as one of the most important Irish artists of the late 19th century. His key contributions include his masterful handling of light and atmosphere, his successful integration of European artistic developments like Naturalism and Impressionism into an Irish context, and, perhaps most importantly, his empathetic and insightful documentation of the lives of ordinary Irish people. His paintings offer not just aesthetic pleasure but also a valuable historical record, rendered with exceptional skill and sensitivity. Walter Frederick Osborne remains a beloved figure in Irish art history, admired for his technical brilliance, his versatility, and the profound humanity that shines through his work.