Walter Gay (1856-1937) stands as a significant figure in American art history, particularly noted for his role as an expatriate artist who achieved considerable fame in France. Born into a traditional New England family in Hingham, Massachusetts, Gay transcended his American roots to become one of the most celebrated painters of elegant European interiors, capturing the refined atmosphere and historical resonance of French châteaux and salons during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work offers a unique window into the tastes and lifestyles of the era, rendered with a distinctive blend of realism and atmospheric sensitivity.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

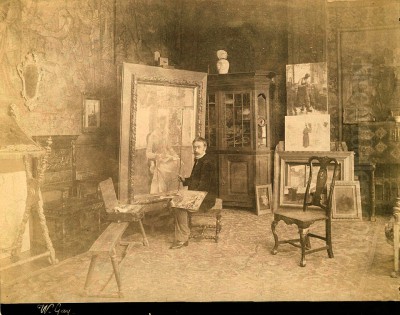

Walter Gay's journey into the art world began in his native Massachusetts. Born in 1856, he demonstrated an early aptitude for art, nurtured within a family that appreciated culture. His uncle, Winkworth Allan Gay, was a landscape painter associated with the Barbizon school, providing a familial connection to the artistic profession. Walter received his initial training in Boston, a city with a burgeoning arts scene. Even in these early stages, his focus often leaned towards still life, particularly floral subjects, showcasing a meticulous attention to detail that would become a hallmark of his later work.

However, the lure of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world in the 19th century, proved irresistible. In 1876, at the age of twenty, Gay made the pivotal decision to move to France to further his artistic education. This move placed him directly into the vibrant, competitive, and stimulating environment of the Parisian art scene, a context that would shape the remainder of his life and career.

Forging a Path in Paris: Training and Influences

Upon arriving in Paris, Gay sought instruction from one of the most respected academic painters of the time, Léon Bonnat. Bonnat's atelier was renowned for its rigorous training, emphasizing draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and a solid grounding in traditional techniques. Studying under Bonnat provided Gay with a strong technical foundation, instilling discipline and a respect for craftsmanship that remained evident throughout his career, even as his subject matter evolved.

During his time in Bonnat's studio and within the broader expatriate artistic community in Paris, Gay formed crucial relationships. Perhaps most significantly, he befriended fellow American John Singer Sargent, who was also making a name for himself. Sargent, known for his dazzling brushwork and insightful portraiture, became a lifelong friend and supporter. It was reportedly Sargent who encouraged Gay to travel to Spain to study the works of the great Spanish master, Diego Velázquez, an experience that would have undoubtedly deepened Gay's understanding of composition, light, and painterly technique.

Another key influence emerged from the work of the Spanish-Italian artist Mariano Fortuny y Marsal. Fortuny was celebrated for his brilliantly colored, highly detailed genre scenes, often depicting historical or exotic subjects with a sparkling, almost jewel-like precision. Gay absorbed Fortuny's sensitivity to light and texture, adapting elements of his vibrant palette and meticulous rendering to his own developing style. Early in his Paris career, Gay focused on genre scenes, often depicting French peasant life with empathy and careful observation, aligning himself with a popular trend in academic painting. He also maintained connections with artists back home, including his friend Robert W. Weir.

A Defining Transition: The Turn to Interiors

A significant shift occurred in Walter Gay's artistic focus around the mid-1890s. While his earlier works depicting peasant life and historical genre scenes had earned him recognition, he began to move away from figurative subjects towards a new, defining theme: the elegant interiors of French homes and châteaux. This transition marked the beginning of the period for which he is most renowned.

Several factors likely contributed to this change. In 1889, Gay married Matilda E. Travers, the daughter of a wealthy New York investor. This marriage brought considerable financial security, freeing Gay from the commercial pressures that might have dictated subject matter for other artists. It allowed him the independence to pursue subjects that genuinely fascinated him. Matilda shared Walter's appreciation for art, history, and elegant living, becoming an active partner in their life and collecting activities.

Furthermore, Gay developed a deep appreciation for 18th-century French architecture and decorative arts. He and Matilda lived immersed in this world, eventually acquiring their own historic property. This personal passion translated directly into his art. He found profound beauty and narrative potential not in the human figure, but in the spaces themselves – rooms rich with history, filled with exquisite objects, and bathed in subtle light. He began to paint the salons, libraries, and galleries of his own homes and those of his friends and acquaintances, capturing the spirit of place.

The Poetry of the Room: Gay's Signature Style

Walter Gay became the preeminent painter of the "portrait of a room." His interiors are rarely, if ever, populated by human figures. Yet, they are far from empty. Instead, they evoke a powerful sense of human presence, suggesting the lives lived within their walls. These are spaces recently vacated or awaiting return, filled with the lingering atmosphere of their inhabitants. This unique approach, often termed the "empty interior," became his signature.

His subjects were typically the grand rooms of 18th-century French châteaux and hôtels particuliers – spaces characterized by boiserie paneling, parquet floors, ornate fireplaces, and tall windows. Gay meticulously rendered the details of these settings, paying close attention to the interplay of light and shadow across surfaces. He delighted in depicting the specific objects that furnished these rooms: gleaming porcelain vases, intricate tapestries, carved and gilded furniture, crystal chandeliers, leather-bound books, and, significantly, paintings and sculptures displayed within the rooms themselves. His works often become inventories of refined taste.

Among his most celebrated works are paintings depicting rooms in his own home, the Château du Bréau, near Fontainebleau, as well as specific, historically significant interiors. Titles like The Boucher Room or The Fragonard Room indicate spaces decorated in the style of, or perhaps containing works by, these iconic Rococo artists (François Boucher, Jean-Honoré Fragonard). Interior of Château du Bréau captures the lived-in elegance of his own residence. These paintings are admired for their intimacy, their quiet elegance, and their ability to transport the viewer into a world of cultivated beauty and historical resonance. They appealed strongly to the Gilded Age collectors who shared Gay's appreciation for European heritage and aristocratic style.

Brushwork, Light, and Atmosphere

Walter Gay's technique was perfectly suited to his subject matter. While grounded in the academic realism learned from Bonnat, his style also incorporated elements associated with Impressionism, particularly in his handling of light and his often fluid, suggestive brushwork. He was a master at capturing the way light filtered through windows, reflecting off polished floors, gleaming on gilded frames, or softly illuminating porcelain and textiles. His brushstrokes could be both precise in rendering detail and loose enough to convey atmosphere and texture effectively.

His palette tended towards refined harmonies, often employing subtle creams, golds, blues, and grays, punctuated by richer notes in the depiction of fabrics or specific objects. He excelled at rendering the varied textures of materials – the cool smoothness of marble, the soft sheen of silk damask, the warm grain of wood paneling, the delicate surface of porcelain. The overall effect is one of sophisticated realism imbued with a palpable sense of mood and place.

Compared to his friend Sargent, whose interiors often served as backdrops for dynamic portraits, Gay's rooms are the primary subject, inviting contemplation of the space itself. While perhaps less overtly atmospheric than some interiors by James McNeill Whistler, Gay's work possesses a unique blend of documentary precision and poetic sensibility. He wasn't merely recording rooms; he was interpreting their character and evoking their history.

Life at Le Bréau: Art and Collecting

Walter and Matilda Gay's life in France was centered around their shared passions for art, history, and elegant living. In 1907, they purchased the Château du Bréau, an 18th-century manor house located in the countryside near the Forest of Fontainebleau, south of Paris. Le Bréau became not only their beloved home but also a primary subject for Walter's paintings. Its gracefully proportioned rooms, filled with their growing collection of art and antiques, provided endless inspiration.

The Gays were avid collectors, focusing primarily on 18th-century French decorative arts, furniture, drawings, and paintings. Their collecting activities deeply informed Walter's artwork; the objects he painted were often part of their personal environment, depicted with the familiarity and affection of ownership. Their home became a reflection of the aesthetic ideals celebrated in his canvases.

Their social circle included artists, writers, and fellow collectors who shared their interests. It is highly likely they were acquainted with the American novelist Edith Wharton, who also lived in France for many years and wrote extensively about French architecture, gardens, and social customs. Wharton's literary descriptions of aristocratic French interiors resonate strongly with the visual world captured in Gay's paintings. They moved within a cosmopolitan milieu that valued European heritage and cultivated taste.

Accolades and Affiliations

Walter Gay achieved significant recognition during his lifetime, both in France and internationally. He exhibited regularly at the prestigious Paris Salon, receiving honors and critical acclaim. A notable early success was winning a gold medal at the Paris Salon of 1888, which helped solidify his reputation. His work was subsequently shown in major international exhibitions in cities such as Antwerp, Vienna, Munich, and Budapest.

He was also chosen to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1896, a mark of his standing in the American art world despite living abroad. His paintings were sought after by prominent American collectors, but also acquired by the French state for its national museums, including the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris – a significant honor for a foreign artist.

Gay was an active member of several important art organizations. He joined the Society of American Artists in 1880 and later served as an officer. In France, he was a loyal member of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts (the "New Salon") and associated with groups like the Société Nouvelle (later Société des Peintres et Sculpteurs). His participation extended to international groups as well, reportedly including the "Group of 33" and the "International Society" around 1896. In 1898, he was elected to the esteemed National Institute of Arts and Letters in the United States. These affiliations underscore his integration into the transatlantic art establishment. Contemporary accounts often referred to him with titles like the "Dean of American Painters in France," reflecting the respect he commanded.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Walter Gay continued to paint actively into the early 20th century, refining his focus on interiors and maintaining a high level of quality and consistency. He remained dedicated to his chosen niche, largely unaffected by the rise of Modernist movements that were revolutionizing the art world around him. His commitment was to capturing the enduring elegance and historical charm of the interiors he loved.

He passed away in 1937 at his home, the Château du Bréau. His wife, Matilda Travers Gay, survived him by several years. A poignant anecdote relates to Matilda's experience during World War II, when another property associated with them, the Château de la Guinguette, was reportedly occupied and damaged by German forces, highlighting the vulnerability of these historic places during conflict (though this occurred after Walter's death).

Matilda ensured the preservation of her husband's legacy and their shared passion for art. She made significant donations from their extensive collection to major museums, most notably the Louvre in Paris, but also to American institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Art Institute of Chicago. These bequests included not only works by Walter Gay himself but also important pieces of 18th-century French art and decorative objects they had collected together.

Walter Gay's influence extends beyond his own canvases. He popularized the genre of the elegant interior portrait, influencing both collectors' tastes and other artists. Painters like William Merritt Chase explored similar themes of refined domestic spaces, perhaps drawing inspiration from Gay's success. Gay also served as an inspiration and connection for younger American artists studying in France, such as Henry Bacon. Today, his works are valued not only for their aesthetic appeal and technical skill but also as invaluable documents of a particular historical milieu – the luxurious, cultured world of the French aristocracy and the expatriate elite during the Belle Époque and beyond.

Conclusion

Walter Gay carved a unique and enduring niche for himself in the history of American and French art. As an American expatriate who found his true subject in the historic interiors of his adopted homeland, he developed a distinctive style characterized by sensitivity to light, meticulous detail, and profound atmospheric evocation. His "empty interiors" are paradoxically full of life, history, and the spirit of their inhabitants. Through his paintings and his life as a collector, Gay celebrated a world of elegance, refinement, and cultural heritage. He remains a master interpreter of the room as portrait, leaving behind a body of work that continues to charm and fascinate viewers with its quiet beauty and historical depth.