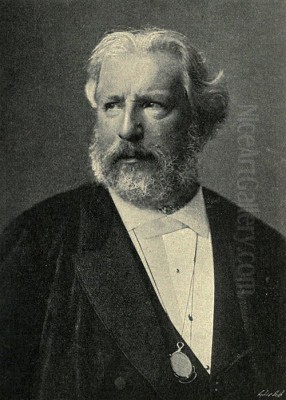

William-Adolphe Bouguereau stands as one of the most prominent and technically gifted painters of the French Academic tradition in the 19th century. Born in La Rochelle, France, on November 30, 1825, and passing away in the same city on August 19, 1905, his life spanned a period of dramatic change in the art world. Bouguereau achieved immense fame and success during his lifetime, celebrated for his meticulously rendered paintings, often featuring mythological, religious, or idyllic genre scenes. His work epitomized the standards of the French Academy and the official Salon, yet his reputation faced a steep decline with the rise of Modernism, only to be significantly re-evaluated in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. This article explores the life, artistic style, key works, educational impact, and complex legacy of this influential artist.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

William Bouguereau was born into a family of wine and olive oil merchants in the coastal city of La Rochelle. While his family initially intended for him to join the family business, his artistic inclinations were evident from a young age. A crucial figure in his early development was his uncle, Eugène Bouguereau, a Catholic priest who recognized and nurtured his nephew's talent. Eugène provided William with instruction in classical and biblical subjects, laying the groundwork for the themes that would dominate his later career.

Recognizing William's potential, Eugène arranged for him to attend the Collège de Pons for his secondary education. It was here that Bouguereau received his first formal art instruction under Louis Sage, a painter who had studied with the great Neoclassical master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. This connection to the Ingres lineage provided Bouguereau with a strong foundation in classical drawing and composition, principles that would remain central to his art throughout his life.

Despite his evident talent, family financial difficulties forced Bouguereau to temporarily abandon his formal studies and return to Bordeaux to assist with the family business. However, his artistic ambitions remained undeterred. To support himself and save money for further education, he undertook commercial work, including designing and hand-painting labels for jams and preserves. This period, though challenging, demonstrated his determination and resourcefulness in pursuing his artistic calling.

Parisian Training and the Prix de Rome

By 1841, Bouguereau had saved enough money and convinced his family to allow him to pursue art more seriously. He enrolled at the Municipal School of Drawing and Painting (École des Beaux-Arts) in Bordeaux. There, he studied under Jean-Paul Alaux and possibly others like Bartolelli and Frederic C. Ross, further honing his skills. His talent quickly gained recognition, and he won first prize in figure painting for a depiction of Saint Roch, an achievement that bolstered his confidence and ambition.

The ultimate goal for any aspiring French artist at the time was Paris, the epicenter of the art world. In 1846, at the age of 21, Bouguereau arrived in the capital with a letter of recommendation and enrolled in the studio of François-Édouard Picot, a respected historical painter and member of the Institut de France. Picot's studio provided rigorous academic training, emphasizing drawing from life, studying the old masters, and mastering complex compositions.

Bouguereau simultaneously gained admission to the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the official state-sponsored art school. Here, he immersed himself in the demanding curriculum, which included intensive life drawing, anatomy lessons, perspective studies, historical costume research, and archaeology. He proved to be an exceptional student, dedicated and hardworking, quickly mastering the academic techniques required for success.

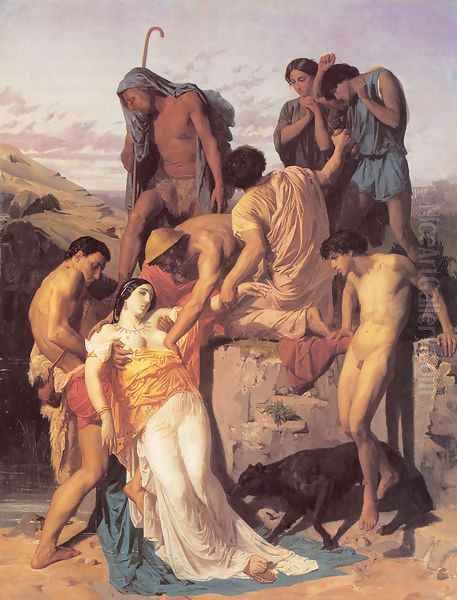

The pinnacle of academic achievement was winning the Prix de Rome, a highly competitive scholarship awarded by the École that allowed the winner to study at the French Academy in Rome for several years. Bouguereau competed fiercely for this prize, finally achieving victory in 1850 with his painting Zenobia Found by Shepherds on the Banks of the Araxes. This prestigious award was a turning point, providing him with the invaluable opportunity to live and study in Italy, immersing himself in the masterpieces of the Renaissance and Antiquity. He studied the works of Raphael, Michelangelo, Titian, and classical sculptors, refining his technique and deepening his understanding of idealized form and classical composition.

The Height of Academic Success

Upon his return to Paris from Rome in 1854, Bouguereau's career quickly ascended. He began exhibiting regularly at the Paris Salon, the official, juried art exhibition that was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition and patronage. His paintings, characterized by their flawless technique, smooth finish (often described as a "licked" surface with no visible brushstrokes), idealized figures, and appealing subject matter, resonated strongly with the tastes of the time.

Bouguereau became a master of Academic painting, skillfully blending elements of Neoclassicism, Realism, and a touch of Romantic sentimentality. His subjects ranged from grand mythological and religious scenes, often featuring beautifully rendered nudes, to charming genre paintings depicting peasant life, particularly young girls and children, presented with an idealized innocence and grace. He possessed an extraordinary ability to render textures – the softness of skin, the sheen of fabric, the play of light – with remarkable precision.

His success at the Salon was phenomenal. He won numerous medals and honors, including the Grand Medal of Honor, and was elected to the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts (part of the Institut de France) in 1876. He received important state commissions for decorative paintings in public buildings, such as the Grand Théâtre in Bordeaux and churches in Paris and La Rochelle. His popularity extended beyond France, particularly to the United States, where wealthy collectors eagerly acquired his works.

Bouguereau's commercial success was also facilitated by astute relationships with leading art dealers of the era. He established long-term arrangements with figures like Adolphe Goupil and, later, Paul Durand-Ruel (who, ironically, would also become a major champion of the Impressionists). These dealers promoted his work internationally through reproductions (especially engravings and photographs), making his images widely accessible and further cementing his fame and financial security. By the late 19th century, Bouguereau was one of the most famous, decorated, and financially successful artists in the world.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Throughout his long and prolific career, Bouguereau produced an estimated 822 paintings. While many followed similar themes and maintained a consistently high level of technical execution, several stand out as defining masterpieces:

Dante and Virgil in Hell (1850): Painted early in his career, shortly before winning the Prix de Rome, this dramatic work depicts a scene from Dante Alighieri's Inferno. It showcases Bouguereau's mastery of anatomy and dynamic composition, capturing the raw energy and torment of the damned with a powerful, almost visceral realism that contrasts with the more serene classicism of his later work. The painting caused a sensation at the Salon.

Nymphs and Satyr (1873): One of Bouguereau's most famous and sensuous mythological paintings, this large canvas depicts a group of playful nymphs attempting to drag a reluctant satyr into a pool. The work is a tour-de-force of composition and the rendering of multiple nude female figures in motion. It exemplifies his ability to combine classical themes with a palpable, albeit idealized, sensuality and charm that appealed greatly to collectors.

The Birth of Venus (1879): Perhaps Bouguereau's most iconic work, this monumental painting was his triumphant submission to the Salon of 1879 and was immediately purchased by the French state for the Musée du Luxembourg. Depicting the goddess Venus standing on a seashell, escorted by cherubs and tritons, it is a quintessential example of Academic mythological painting. While drawing inspiration from Renaissance depictions like Botticelli's, Bouguereau's version is distinctly 19th-century in its smooth, photographic realism and idealized sensuality. It directly competed with similar Salon successes like Alexandre Cabanel's Birth of Venus (1863).

The Shepherdess (1882 / 1889): Bouguereau painted numerous canvases featuring young peasant girls, often shepherdesses, embodying idealized rustic innocence and beauty. Works like The Little Shepherdess (1889), showing a young girl standing barefoot, staff in hand, gazing directly at the viewer with a serene expression, were immensely popular. An earlier work titled La Pastour or The Shepherdess from 1882 also captures this theme. These paintings, while sentimental, demonstrate his skill in capturing youthful charm and integrating figures seamlessly into landscape settings.

Innocence (1893): This work exemplifies Bouguereau's religious paintings, often imbued with a tender sentimentality. It depicts a young woman, reminiscent of the Madonna, holding a sleeping infant (representing Christ) and a lamb (symbolizing sacrifice). The figures are rendered with exquisite softness and purity, conveying themes of maternal love, piety, and innocence. It is considered one of his most touching and popular religious images.

The Song of the Nightingale (undated): Representing his genre scenes, this painting shows a young woman seated in a landscape, listening intently as a nightingale perches nearby. It captures a quiet moment of connection with nature, rendered with Bouguereau's characteristic technical polish and gentle emotional tone.

Bouguereau as Educator: The Académie Julian

Beyond his own prolific output, Bouguereau exerted a significant influence on the next generation of artists through his role as a teacher. While he also taught at the École des Beaux-Arts, his most extensive teaching activities took place at the Académie Julian. Founded by Rodolphe Julian, this private art school became a major alternative and supplement to the official École, particularly notable for welcoming female students and foreign artists who faced restrictions at the state institution.

From the 1870s (officially teaching drawing from 1875 and remaining active through the 1880s and 1890s), Bouguereau became one of the Académie Julian's most respected and sought-after instructors. He visited the studios regularly, offering critiques and guidance to hundreds, possibly thousands, of students from around the world. His teaching emphasized the foundational principles of Academic art: rigorous drawing, accurate observation, mastery of anatomy, and the careful construction of compositions.

He was known for being a demanding but fair teacher. While insisting on mastery of traditional techniques, some accounts suggest he was not entirely closed off to newer trends and encouraged students to find their own paths once they had mastered the fundamentals. His students included a diverse array of artists who would go on to achieve recognition in various styles.

Among his notable students were:

Elizabeth Jane Gardner: An accomplished American painter who became Bouguereau's wife.

Cecilia Beaux: A leading American portrait painter.

Jefferson David Chalfant: An American painter known for his trompe-l'oeil works.

Henri Matisse: The future Fauvist leader studied briefly under Bouguereau, though he ultimately rejected the academic approach. Matisse later recalled Bouguereau's emphasis on precise drawing.

Georges Rochegrosse: A French historical and Orientalist painter.

Gustave Doyen: A French painter known for portraits and historical scenes.

Eanger Irving Couse: An American painter famous for his depictions of Native Americans.

Lawton S. Parker: An American Impressionist painter.

Douglas Volk: An American portrait and figure painter.

Louis Aston Knight: An American landscape painter, son of Daniel Ridgway Knight (another popular expatriate artist).

Bouguereau's dedication to teaching ensured the transmission of academic skills and principles, shaping the training of countless artists, even those who would later diverge significantly from his style.

Contemporaries: Rivalry and Respect

Bouguereau operated within a vibrant and competitive art world. As a leading figure of the Academic establishment, his position was both esteemed and challenged. He had rivals within the Academic system itself, such as Hugues Merle, whose sentimental genre scenes and polished technique often drew comparisons with Bouguereau's work. They competed for honors, commissions, and collector attention at the Salon.

His relationship with the emerging avant-garde movements, particularly Impressionism, was one of mutual opposition. Impressionists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir rejected the very foundations of Academic art that Bouguereau championed. They criticized his highly finished surfaces, idealized subject matter, and reliance on historical or mythological themes as artificial and out of touch with modern life. They favored capturing fleeting moments, the effects of light, and contemporary scenes with looser brushwork and brighter palettes.

For his part, Bouguereau, along with fellow influential Academicians like Jean-Léon Gérôme and Alexandre Cabanel, largely dismissed the Impressionists' work as unfinished and lacking in proper drawing and skill. As a powerful member of the Salon jury and the art establishment, Bouguereau held considerable sway in limiting the acceptance and exhibition opportunities for these avant-garde artists within the official system. This ideological and aesthetic divide defined much of the artistic discourse in the latter half of the 19th century.

Despite these conflicts, Bouguereau maintained professional relationships with figures across the art world, including dealers like Durand-Ruel who navigated both the academic and impressionist markets. He also associated with other successful painters who shared similar approaches or themes, such as the Realist painter Léon Lhermitte, known for his depictions of rural labor. Bouguereau's career unfolded amidst a complex network of alliances, rivalries, and aesthetic debates that shaped the trajectory of French art.

Later Years and Personal Life

Bouguereau maintained a rigorous work schedule throughout his life, often spending long hours in his studio. His personal life saw both joy and sorrow. He married Marie-Nelly Monchablon in 1856, and they had five children. Tragically, only one daughter, Henriette, survived to adulthood; his wife Nelly and four children predeceased him, causing him immense grief.

Later in life, he formed a close relationship with one of his most devoted students, the American painter Elizabeth Jane Gardner. Despite societal disapproval and resistance from his family (particularly his surviving daughter), they maintained a long engagement and finally married in 1896, after the death of Bouguereau's mother who had opposed the union. Elizabeth was an accomplished artist in her own right, her style heavily influenced by Bouguereau's. Their marriage appears to have been a happy one, lasting until his death.

In the spring of 1905, Bouguereau suffered a significant personal blow when his Paris house and studio were burgled. The loss, coupled with his advancing age and perhaps the cumulative effect of past sorrows, reportedly affected him deeply. Later that summer, while staying in his hometown of La Rochelle, William-Adolphe Bouguereau died of heart disease on August 19, 1905, at the age of 79. He was buried in the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris alongside his first wife and children.

Legacy and Reappraisal

Immediately following Bouguereau's death, his reputation, already under attack from proponents of Modernism, began a precipitous decline. For much of the 20th century, his work was widely dismissed by critics, curators, and art historians. He came to symbolize everything the Modernist avant-garde had rebelled against: conservative taste, bourgeois sentimentality, photographic literalness devoid of "true" artistic expression, and repetitive, formulaic compositions. His paintings were removed from view in many museums, relegated to storage or sold off cheaply. Figures like Degas famously quipped about "Bouguereaute" (Bouguerized) art, using his name as a term of derision for overly slick, academic work.

However, beginning in the late 1970s and accelerating through the 1980s and into the 21st century, a significant reappraisal of Bouguereau and 19th-century Academic art began. This was fueled by several factors: a renewed interest in traditional painting techniques, a reaction against the perceived excesses and obscurities of late Modernism and Postmodernism, the efforts of revisionist art historians challenging the dominant Modernist narrative, and the advocacy of collectors and organizations dedicated to realist art.

Major retrospective exhibitions, such as the one organized by the Petit Palais in Paris, the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford in 1984-1985, reintroduced his work to a wider public. Scholars began to re-examine his technical mastery, his role as an educator, and his place within the complex social and cultural context of the 19th century.

Today, Bouguereau's reputation is far more nuanced. While criticisms of sentimentality and conservatism persist in some quarters, there is widespread acknowledgment of his extraordinary technical skill. His draftsmanship, his handling of paint to create flawless surfaces, his understanding of anatomy, and his compositional abilities are recognized as being of the highest order within the Academic tradition. His paintings now command high prices at auction, and he is once again featured prominently in museum collections. His influence can be seen in contemporary realist painters who admire and seek to emulate his technical prowess and dedication to figurative art.

Conclusion

William-Adolphe Bouguereau remains a pivotal, if sometimes controversial, figure in 19th-century art history. He was the embodiment of French Academic painting at its zenith, achieving unparalleled success and recognition during his lifetime through a combination of exceptional talent, rigorous training, hard work, and an astute understanding of the prevailing tastes and systems of the art world. His meticulously crafted paintings of mythological beauties, pious Madonnas, and idealized peasant children captivated audiences and defined the standards of the official Salon for decades.

His subsequent fall from critical favor during the dominance of Modernism, followed by his remarkable resurgence in recent decades, highlights the shifting tides of artistic taste and historical interpretation. While his work may lack the revolutionary edge of the Impressionists or the raw emotional power found in other traditions, Bouguereau's contribution lies in his absolute mastery of the academic style he inherited and perfected. As a painter of immense technical skill and a dedicated educator who shaped a generation of artists, William-Adolphe Bouguereau's complex legacy continues to be debated, studied, and admired, securing his enduring place in the annals of art history.