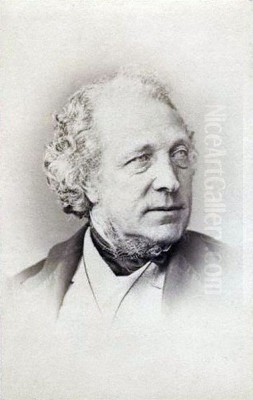

William Leighton Leitch stands as a significant figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century British art. A highly accomplished watercolour painter, particularly renowned for his evocative landscapes of Scotland and Italy, Leitch carved a unique path that blended artistic creation with influential teaching, most notably serving as the long-term drawing master to Queen Victoria and the Royal Family. His career spanned a period of immense change and development in British art, and his work reflects both the enduring influence of earlier masters and the specific sensibilities of the Victorian era.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Glasgow

Born in Glasgow on November 2nd, 1804, William Leighton Leitch's entry into the world of art was not preordained. His father, a soldier who had later become a successful businessman, harboured ambitions for his son to pursue a more conventional and potentially lucrative career in law. However, the young Leitch displayed an innate passion for drawing from an early age, a calling that proved irresistible despite paternal disapproval.

Anecdotes suggest that Leitch's dedication was such that he would practice his drawing skills in secret, often by candlelight late at night, to avoid his father's notice. This early determination hinted at the perseverance that would characterise his artistic journey. His formal education included a period at the Highland Society School, but his artistic inclinations soon led him towards practical application.

Initially, Leitch found employment that utilised his developing skills, working for a time as a weaver and then with a house painter and decorator named Mr. Harbut. These early experiences, though perhaps not directly fine art, likely provided him with a foundational understanding of materials, surfaces, and perhaps even large-scale design, which would prove useful later in his career.

His true artistic training began under the guidance of David MacNee, a prominent Glasgow portrait painter who would later serve as President of the Royal Scottish Academy. Studying with MacNee provided Leitch with crucial foundational skills in drawing and painting, embedding him within the burgeoning artistic community of Glasgow. This period was vital in shaping his technical abilities and artistic aspirations.

Theatrical Foundations and the Move to London

Leitch's first significant professional role was not in easel painting but in the dynamic world of theatre. He secured a position as a scene-painter at the Theatre Royal in Glasgow. This work, demanding rapid execution, an understanding of perspective, and the ability to create dramatic effects on a large scale, provided invaluable practical experience. Scene painting honed his compositional skills and his ability to handle broad areas of colour and light, elements that would later inform his landscape watercolours.

However, the precarious nature of the theatre world soon impacted his career. When the Theatre Royal in Glasgow faced financial difficulties and closed, Leitch sought opportunities elsewhere. Around 1824, encouraged by his burgeoning talent and perhaps seeking a larger stage for his ambitions, he made the pivotal decision to move to London.

In the bustling metropolis, Leitch continued to work in scene painting. Crucially, this period brought him into contact with established figures in the art world who were also involved in theatrical work. He met and befriended Clarkson Stanfield and David Roberts, both highly successful painters who had themselves started as scene painters. Stanfield was already renowned for his dramatic marine and landscape paintings, while Roberts was gaining fame for his architectural and topographical views, particularly of Spain and the Near East.

The support and guidance of Stanfield and Roberts were instrumental. They recognised Leitch's talent and helped him secure work, including a position painting scenery at the Queen's Theatre (likely referring to Her Majesty's Theatre or a similar prominent venue). This association not only provided employment but also exposed Leitch to the highest standards of the craft and integrated him further into London's artistic circles. He learned much from observing their techniques, particularly their mastery of watercolour, which was increasingly becoming his preferred medium.

The Grand Tour: Italy and Artistic Maturation

A desire for further artistic development and exposure to the landscapes and masterpieces of the Continent prompted Leitch to embark on an extended tour abroad. From 1833 to 1837, he travelled extensively, primarily focusing on Italy, but also visiting Switzerland, Germany, and Sicily. This period was transformative, profoundly shaping his artistic vision and subject matter.

Italy, with its classical ruins, picturesque landscapes, and unique quality of light, captivated him. He spent considerable time sketching and painting en plein air, absorbing the atmosphere and topography of Rome, Venice, Naples, and the Italian countryside. The experience of directly observing the landscapes painted by masters like Claude Lorrain, whose idealized compositions and handling of light had long influenced British landscape art, was deeply impactful.

His time in Italy provided him with a rich repository of subjects that would feature in his work for the rest of his career. He developed a particular affinity for the Italian light and atmosphere, which he sought to capture in his watercolours. His technique evolved, becoming more refined and confident as he grappled with rendering complex architectural details, expansive vistas, and the interplay of light and shadow under the Mediterranean sun.

During his travels, Leitch also engaged with fellow artists. A notable encounter occurred in Venice, where he met and formed a friendship with the Hungarian painter Miklós Barabás. Such interactions fostered a valuable exchange of ideas and perspectives, enriching his experience beyond solitary study. The Grand Tour solidified Leitch's commitment to landscape painting and equipped him with the skills and inspiration to pursue it at a high level upon his return to Britain.

Return to London: Teaching and Landscape Painting

Leitch returned to London in 1837, his artistic identity significantly sharpened by his experiences abroad. While he continued to paint, he increasingly turned his attention to teaching watercolour painting, an endeavour that would define a major part of his career and legacy. His reputation as a skilled artist, combined with his refined technique and amiable personality, made him a sought-after instructor.

He quickly established himself as a successful private tutor, attracting pupils from affluent and aristocratic circles. His teaching methods were systematic and effective, emphasizing strong drawing skills as a foundation, combined with a nuanced understanding of watercolour techniques – washes, layering, colour mixing, and the strategic use of bodycolour or scraping out for highlights.

His own painting continued to develop. He drew heavily on the sketches and studies made during his European travels, producing finished watercolours depicting Italian and, increasingly, Scottish landscapes. His style, while rooted in the topographical tradition, showed the influence of J.M.W. Turner in its pursuit of atmospheric effects, luminous skies, and a more poetic interpretation of landscape. However, Leitch generally retained a greater degree of structural clarity and detailed rendering compared to Turner's later, more abstract works.

He began exhibiting his work more regularly at London's prestigious venues. Between 1841 and 1861, he showed several paintings at the Royal Academy, contributing to his growing visibility and reputation within the mainstream art establishment. His subjects often featured identifiable locations, rendered with accuracy but imbued with a romantic sensibility.

Master of Watercolour Technique

Leitch's mastery of the watercolour medium was central to his success both as an artist and a teacher. He possessed a deep understanding of the properties of watercolour paints and papers, allowing him to achieve remarkable effects of light, transparency, and atmosphere. His technique was characterised by clean, luminous washes, careful drawing, and a sophisticated sense of composition.

Unlike some contemporaries who favoured heavy use of bodycolour (opaque watercolour), Leitch often relied on the transparency of pure watercolour washes, allowing the white of the paper to shine through and create luminosity. He was adept at layering washes to build depth and tonal variation without losing freshness. His palette was typically bright and harmonious, reflecting the clear light he admired in Italy and sought in the varied skies of Britain.

His compositions were carefully constructed, often balancing architectural elements with natural scenery. This likely stemmed from his early training in scene painting, which required strong spatial organisation. Whether depicting a ruined castle on a Scottish loch or a bustling piazza in Rome, his works demonstrate a keen eye for perspective and structural coherence.

Compared to other leading watercolourists of the time, Leitch occupied a distinct position. He shared an interest in atmospheric effects with figures like Copley Fielding and David Cox, but perhaps with a greater emphasis on classical structure. While less ruggedly expressive than Cox or Peter De Wint in their depictions of the British countryside, Leitch brought a continental elegance and refinement to his subjects. His work stands apart from the detailed architectural focus of Samuel Prout, though he shared Prout's skill in rendering buildings within a landscape context.

Royal Patronage: Drawing Master to Queen Victoria

Leitch's career reached a pinnacle of prestige when he secured the position of drawing master to Queen Victoria. Around 1846, he was introduced to the Queen, reportedly through the influence of Lady Canning, one of his pupils and a lady-in-waiting. This appointment marked the beginning of a long and distinguished association with the Royal Family that lasted for an impressive 22 years.

He instructed not only the Queen herself, who was a keen amateur artist, but also Prince Albert and their children, including the future King Edward VII (as Prince of Wales) and other royal princesses. This role required not only artistic skill but also diplomacy and pedagogical patience. Leitch proved adept at navigating the demands of teaching within the royal household.

His teaching methods for his royal pupils mirrored his general approach: emphasizing foundational drawing, careful observation, and the systematic application of watercolour techniques. Surviving examples of instructional materials, such as annotated lists of colours and demonstration sketches (like the documented Miss Daisy Lowe's List of Colours, likely similar to materials used for royal tuition), reveal his methodical approach. He provided clear guidance on colour mixing and application to achieve specific effects.

Beyond technical instruction, Leitch aimed to cultivate artistic appreciation. He encouraged his pupils to study the works of established masters and potentially guided them during visits to galleries and collections. Queen Victoria's own watercolours and sketches from this period often show a clear affinity with Leitch's style, particularly in landscape subjects and handling of washes. While Edward Lear also provided some drawing lessons to the Queen, Leitch's tenure was far longer and likely more formative.

This royal appointment significantly enhanced Leitch's social standing and professional reputation. It solidified his position as one of the foremost drawing masters of the Victorian era and brought his name to wider public attention. His influence extended through his royal pupils and the many other members of the aristocracy he taught, shaping amateur artistic practice in Britain for decades.

Professional Recognition and the Institute of Painters in Watercolours

While royal patronage brought prestige, Leitch also sought recognition within the established structures of the London art world. He became closely associated with the Institute of Painters in Watercolours (initially founded as the New Society of Painters in Watercolours in 1831). This society was established partly in opposition to the perceived exclusivity of the older Society of Painters in Water-Colours (the 'Old' Society, later the Royal Watercolour Society or RWS).

The Institute provided an important exhibition venue for artists working in watercolour. Leitch was elected a member in 1862 and quickly rose to prominence within the organization. In the same year, he was elected Vice-President, a position he held with dedication for two decades until his death. His long service underscores his commitment to the society and his respected standing among his peers.

His involvement with the Institute placed him alongside other prominent watercolourists associated with the society, such as Myles Birket Foster, known for his charming rustic scenes, although Leitch's style remained distinct, generally broader in handling and less focused on anecdotal detail than Foster's work. Exhibiting regularly at the Institute's gallery ensured his work remained visible to the public and collectors.

Despite his success as a teacher and his role at the Institute, Leitch's profile as an exhibiting artist at the Royal Academy seemed to diminish after the early 1860s, possibly due to his increasing teaching commitments and his focus on the Institute. Nonetheless, his reputation as a master watercolourist was firmly established.

Key Works and Artistic Themes

Throughout his long career, William Leighton Leitch produced a substantial body of work, primarily landscapes in watercolour. While a comprehensive catalogue is complex due to his extensive teaching output (which often involved demonstration pieces), several works are frequently cited as representative of his style and preferred subjects.

His Italian subjects remained a cornerstone of his output. Works like Giulio Lorenzo, Vatican (1835) and The Pantheon, Rome (1835), likely based on sketches from his Grand Tour, showcase his ability to combine architectural accuracy with atmospheric rendering. The Cavalli Marini Fountain, Borghese Gardens, Rome is another well-known example, capturing the play of light on water and stone in the famous Roman park. Catania looking towards Sortino demonstrates his interest in the landscapes of Sicily.

He was equally adept at depicting the scenery of his native Scotland and other parts of Britain. Peel Castle (1851) exemplifies his treatment of historical architecture within a dramatic natural setting, a theme popular in the Romantic era. A Castle on a River and numerous views of Scottish lochs, mountains, and coastal scenes reflect his deep connection to these landscapes. His depictions often emphasize the grandeur and sometimes melancholic beauty of the scenery.

Later in his career, his royal connections led to commissions or opportunities to paint views of royal residences like Osborne House on the Isle of Wight and Balmoral Castle in Scotland. His drawings of Osborne were used as illustrations for W. H. D. Adams's book The History, Topography, and Antiquities of the Isle of Wight (1856), demonstrating the practical application of his topographical skills.

Across these varied subjects, Leitch's work consistently displays a refined sensibility, technical polish, and a focus on capturing the effects of light and atmosphere. His paintings are often characterized by a sense of calm and order, even when depicting dramatic landscapes, reflecting a classical underpinning to his romantic inclinations.

Legacy and Influence

William Leighton Leitch died at his home in St John's Wood, London, on April 25th, 1883, at the age of 79. He left behind a significant legacy, primarily as a master watercolourist and an exceptionally influential teacher. His impact was felt most directly through his decades of instruction, particularly within the Royal Family and the British aristocracy. He helped shape the standards and techniques of amateur watercolour painting during the Victorian era.

As an artist, Leitch occupies a respected place within the tradition of British watercolour painting. While perhaps not possessing the groundbreaking originality of Turner or the raw expressive power of David Cox, he was a highly accomplished technician and a sensitive interpreter of landscape. His works are admired for their elegance, luminosity, and compositional harmony. He successfully synthesized influences from the classical landscape tradition of Claude Lorrain with the atmospheric concerns of Romanticism, as exemplified by Turner, creating a style that was both accomplished and accessible.

His long tenure as Vice-President of the Institute of Painters in Watercolours highlights his standing within the professional art community of his time. He contributed to the growing prestige and popularity of the watercolour medium throughout the nineteenth century. His works are held in numerous public collections, including the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, and the Royal Collection Trust, ensuring their continued visibility.

While critical opinion might place him slightly below the very highest tier of British watercolour masters, his skill, influence as a teacher, and association with Queen Victoria secure his importance. He represents a particular strand of Victorian landscape painting – refined, technically superb, and imbued with a gentle romanticism. The critic John Ruskin, the great arbiter of taste in Victorian art, likely appreciated Leitch's truth to nature and technical skill, though perhaps finding him less spiritually profound than Turner. Leitch's enduring appeal lies in the quiet beauty and masterful execution of his landscape watercolours.

Conclusion

William Leighton Leitch's life journey took him from clandestine drawing practice in Glasgow to the heart of the British establishment as drawing master to the Queen. His career exemplifies dedication to craft, a deep love for landscape, and a remarkable talent for teaching. As a scene painter, he learned composition and effect; as a traveller, he absorbed the light and forms of Italy; as a mature artist, he perfected a luminous watercolour technique influenced by Turner but distinctly his own.

His association with artists like David Roberts and Clarkson Stanfield early in his career, his friendship with figures like Miklós Barabás abroad, and his long leadership role at the Institute of Painters in Watercolours place him firmly within the network of nineteenth-century European art. His representative works, depicting the landscapes of Italy and Scotland with elegance and atmospheric sensitivity, remain admired examples of Victorian watercolour painting.

More than just a skilled painter, Leitch was a pivotal figure in art education, shaping the artistic pursuits of Queen Victoria and countless others. His legacy endures not only in his beautiful watercolours held in collections worldwide but also in the lasting impact he had on the appreciation and practice of art in nineteenth-century Britain. He remains a key figure for understanding the rich and diverse world of Victorian landscape art.