Władysław Ślewiński stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. A Polish painter حياته (his life) and work bridge the vibrant artistic circles of Paris and Pont-Aven with the burgeoning national artistic identity of the Young Poland movement. Deeply influenced by his association with Paul Gauguin, Ślewiński forged a distinctive style characterized by simplified forms, expressive color, and a profound connection to nature, whether the rugged coasts of Brittany or the majestic peaks of the Tatra Mountains. His journey is one of artistic discovery, personal conviction, and a quiet dedication to his craft that left an indelible mark on Polish art.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings in Poland

Born in 1856 in Białynin, near Mikołajew, within the Russian-partitioned Poland, Władysław Ślewiński hailed from a landowning noble family. His early life was marked by the privileges of his class, but also by the undercurrents of national aspiration and the complexities of existing under foreign rule. The Poland of his youth was a nation struggling to maintain its cultural identity, a sentiment that would later find expression in the Young Poland movement, with which Ślewiński became associated.

His initial forays into art were not those of a prodigious talent immediately recognized. He first took up drawing lessons in Warsaw at the private studio of Wojciech Gerson, a prominent Polish painter of the realist school and a respected teacher who had instructed many notable Polish artists, including Józef Chełmoński and Leon Wyczółkowski. However, Ślewiński did not complete his studies with Gerson. His path to becoming a professional artist was not straightforward and was significantly impacted by family circumstances. In 1886, due to his father's mismanagement of the family estate, significant debts were incurred, leading to the property being pursued by Russian tax authorities. This financial crisis and the ensuing legal troubles compelled the young Ślewiński to leave Poland.

This departure, initially driven by necessity, would prove to be a pivotal turning point in his life. He set his sights on Paris, the undisputed capital of the art world in the late 19th century, a magnet for aspiring artists from across Europe and beyond. For Ślewiński, it was a leap into the unknown, a move away from the provincial concerns of his homeland towards the epicenter of artistic innovation.

Parisian Immersion: The Academies and the Avant-Garde

Arriving in Paris around 1888, Ślewiński was thrust into a city teeming with artistic ferment. The Impressionist revolution had already reshaped the artistic landscape, and new movements like Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and the nascent Art Nouveau were challenging established conventions. For a newcomer, especially one with limited formal training and practical skills, navigating this dynamic environment was undoubtedly daunting.

Ślewiński sought to bolster his artistic foundations by enrolling in some of the city's famed private art academies. He spent a brief period, approximately two months, at the Académie Julian, a popular institution known for its less rigid approach compared to the official École des Beaux-Arts. It attracted a diverse international student body, including artists like Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Vuillard, and later, members of the Nabis group. Following this, he studied for a more extended period, about two years, at the Académie Colarossi. Like Julian's, Colarossi was an alternative art school that offered life drawing classes and was frequented by many foreign artists, including Amedeo Modigliani and the Czech artist Alphonse Mucha.

These academic experiences provided him with essential training in drawing and painting from life, but the true direction of his art would be shaped by encounters outside the formal studio system. Paris was a city of artistic exchange, where cafes, studios, and galleries buzzed with discussions about new theories and approaches to art. It was in this milieu that Ślewiński would find his most crucial artistic guide.

The Defining Encounter: Paul Gauguin and the Pont-Aven School

The most significant event in Władysław Ślewiński's artistic development was his meeting with Paul Gauguin. This encounter, likely occurring around 1889, transformed Ślewiński's understanding of art and set him on a path aligned with the Post-Impressionist avant-garde. Gauguin, by then a charismatic and controversial figure, had already broken with Impressionism and was pioneering a new style known as Synthetism, or Cloisonnism, characterized by bold outlines, flat areas of color, and a subjective, symbolic approach to subject matter.

Ślewiński became a devoted student and admirer of Gauguin, drawn to his powerful artistic vision and his rejection of naturalistic representation in favor of emotional and spiritual expression. He joined Gauguin and his circle of followers in Brittany, primarily in the village of Pont-Aven and later in Le Pouldu. This region, with its rugged landscapes, distinct cultural traditions, and perceived "primitivism," had become a haven for artists seeking an alternative to the urban sophistication of Paris.

The Pont-Aven School, as the group of artists around Gauguin came to be known, included figures like Émile Bernard, Paul Sérusier, Charles Laval, Meyer de Haan, and the Irish painter Roderic O'Conor. These artists shared a desire to move beyond the fleeting optical impressions of Impressionism, seeking instead to convey deeper meanings and emotions through simplified forms and expressive color. Ślewiński absorbed these principles, and his work from this period shows a clear affinity with Gauguin's aesthetic. He was not merely an imitator; rather, he internalized the core tenets of Synthetism and adapted them to his own temperament and vision.

Gauguin's influence on Ślewiński was profound, extending beyond artistic technique to a broader philosophy of art. Gauguin famously advised artists to paint from memory and imagination rather than directly from nature, to synthesize their observations into a more potent and personal artistic statement. This approach resonated deeply with Ślewiński, who began to produce works that emphasized decorative harmony, simplified forms, and a strong sense of mood. His friendship with Gauguin was close, and Gauguin himself recognized Ślewiński's talent, even acquiring one of his drawings, a portrait of Anna Javanaise.

The Breton Period: Forging a Personal Style

Brittany became Ślewiński's spiritual and artistic home for many years. The wild, untamed coastline, the deep blue of the Atlantic, the distinctive granite architecture, and the traditional way of life of the Breton people provided him with a rich source of inspiration. His paintings from this period are predominantly landscapes and seascapes, imbued with a sense of melancholy and a profound connection to the elemental forces of nature.

Works such as Cliffs in Brittany (Musée de Pont-Aven) and Sea in Brittany (National Museum in Krakow) exemplify his Breton style. These paintings are characterized by their simplified compositions, often featuring high horizons, flattened perspectives, and broad areas of unmodulated color bounded by strong outlines, a technique reminiscent of Japanese woodblock prints and medieval stained glass, both of which influenced Gauguin and his circle. Ślewiński's palette often favored muted tones, blues, greens, and grays, capturing the atmospheric quality of the Breton coast.

Beyond landscapes, Ślewiński also painted portraits and still lifes during his time in Brittany. His portraits, such as Woman with Dark Hair, often convey a sense of introspection and quiet dignity. His still lifes, like Anemones, demonstrate his ability to find beauty and decorative potential in simple, everyday objects, arranging them with a focus on harmonious color relationships and balanced compositions. A notable work, Two Breton Women with a Basket of Apples, showcases his engagement with the local people, depicting them with a sense of respect and an eye for the decorative patterns of their traditional attire, synthesized into a cohesive artistic statement.

His time in Pont-Aven and Le Pouldu made him an important member of the local art community. He was not merely a follower but an active participant in the artistic dialogues that shaped Post-Impressionism. His commitment to the principles learned from Gauguin was unwavering, even after Gauguin's departure for Tahiti. Ślewiński continued to explore and refine his Synthetist approach, developing a style that was both indebted to his mentor and distinctly his own.

Artistic Philosophy and Technical Approach

Ślewiński's artistic philosophy was deeply shaped by Gauguin's assertion that an artist must "either completely accept or completely reject" his ideas. This suggests a commitment to a singular, powerful artistic vision, one that eschews compromise and seeks a fundamental truth in art. For Ślewiński, this meant moving beyond the superficial appearances of reality to capture the underlying essence or "soul" of his subjects. He believed art should not merely imitate nature but interpret it, imbuing it with personal feeling and symbolic meaning.

His technique reflected this philosophy. He favored simplification of form, reducing subjects to their essential shapes and lines. His compositions often employed flat planes of color, rejecting traditional modeling and perspective to create a more decorative and emotionally resonant surface. The use of strong outlines, a hallmark of Cloisonnism, helped to define these color areas and lend a sense of structure and clarity to his paintings.

While his palette could be subdued, particularly in his Breton seascapes, he was a sensitive colorist, capable of achieving rich harmonies and subtle tonal variations. He sought a "朴素 (pǔsù - simple, unadorned) and 真诚 (zhēnchéng - sincere)" aesthetic, as described in the initial information, suggesting a desire for authenticity and directness in his artistic expression, free from academic artifice or Impressionistic virtuosity for its own sake. His art aimed to evoke a mood, a feeling, rather than to provide a literal transcription of the visible world. This aligns with the broader Symbolist currents of the late 19th century, which saw artists like Odilon Redon and Gustave Moreau exploring the realms of dream, myth, and inner experience.

Return to Poland and the Young Poland Movement

After many years in France, Ślewiński made the decision to return to Poland, residing there primarily between 1905 and 1910. This period coincided with the height of the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement, a significant cultural and artistic phenomenon that swept through Polish society at the turn of the century. Young Poland was a multifaceted movement encompassing literature, music, and the visual arts, characterized by a spirit of modernism, a revival of interest in Polish folklore and tradition, and a strong sense of national identity.

Artistically, Young Poland embraced a range of styles, including Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and early Expressionism. Key figures in the visual arts included Stanisław Wyspiański, a versatile artist known for his paintings, stained glass, and theatrical designs; Józef Mehoffer, celebrated for his monumental stained glass and murals; Jacek Malczewski, whose work is rich in Polish patriotic and mythological symbolism; and Olga Boznańska, a renowned portraitist with a distinctive psychological insight. Leon Wyczółkowski, another prominent figure, excelled in landscape and portraiture, often capturing the essence of Polish nature.

Ślewiński, with his Parisian avant-garde credentials and his commitment to a modern, expressive style, naturally found a place within the Young Poland milieu. His art, with its emphasis on emotional content and decorative qualities, resonated with the movement's aesthetic aims. During his time in Poland, he took on a teaching role, serving as a professor at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts from 1908 to 1910. In this capacity, he had the opportunity to influence a new generation of Polish artists, sharing the principles he had absorbed in France. He also organized his own art school in Poronin, a village in the Tatra Mountains.

His involvement with Young Poland marked a significant phase in his career, connecting his international experience with the specific cultural context of his homeland. He participated in exhibitions and became a recognized figure in the Polish art scene, contributing to the modernization of Polish art.

The Tatra Mountains and Later Works

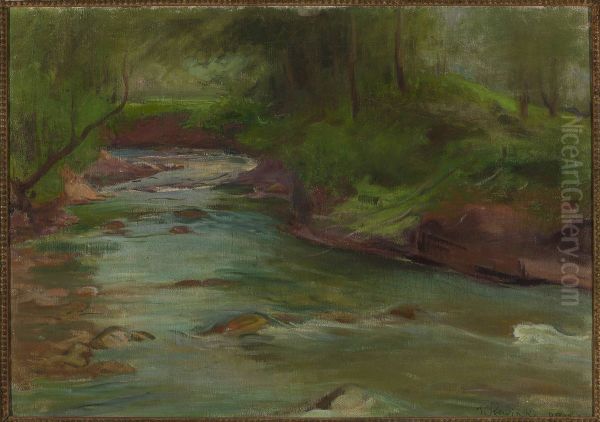

While Brittany had been the primary focus of his landscape painting for many years, Ślewiński's return to Poland led him to discover a new source of inspiration: the Tatra Mountains. This majestic mountain range, located on the border between Poland and Slovakia, held a special significance in Polish culture, often seen as a symbol of national strength and natural beauty.

His paintings of the Tatras, such as Mountain Stream in the Tatra Mountains, reveal a continued commitment to his Synthetist principles, adapted to this new and dramatic subject matter. He captured the rugged grandeur of the mountains, the play of light on their peaks, and the unique atmosphere of the highland region. These works often possess a sense of monumentality and a deep reverence for nature, akin to his earlier Breton seascapes but translated into a different geographical and cultural context. The Poronin Orphan, a poignant portrait from this period, likely reflects his engagement with the local community in the Tatra region, showcasing his enduring interest in human subjects alongside his landscape work.

His later works, whether landscapes, portraits, or still lifes, continued to demonstrate his mastery of simplified form and expressive color. He remained true to the artistic convictions he had forged in his youth, refining his style rather than undergoing radical transformations. His artistic journey was one of consistent development along a path defined early in his career through his association with Gauguin.

Portraits and Still Lifes: Intimate Expressions

Throughout his career, alongside his significant contributions to landscape painting, Władysław Ślewiński consistently engaged with portraiture and still life. These genres offered him different avenues for exploring his artistic concerns, allowing for more intimate and focused studies of form, color, and character.

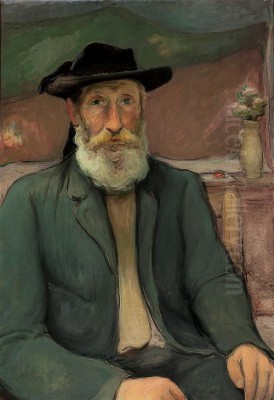

His portraits, such as the aforementioned Woman with Dark Hair or the Portrait of Anna Javanaise (the drawing admired by Gauguin), are notable for their psychological penetration and their departure from conventional academic likeness. Ślewiński was less interested in a meticulous rendering of features than in capturing the sitter's inner state or a particular mood. He often simplified the background, focusing attention on the figure, and used color and line to convey personality and emotion. His portraits share the decorative sensibility of his landscapes, with an emphasis on harmonious arrangement and expressive form. The Poronin Orphan is a particularly moving example, conveying vulnerability and resilience through his characteristic simplification and empathetic portrayal.

Ślewiński's still lifes, such as Anemones or Still Life with Vase, are exquisite examples of his ability to transform humble objects into subjects of profound artistic contemplation. He approached still life with the same principles of simplification and decorative harmony that guided his other work. Flowers, fruit, and simple household items were arranged with a keen eye for color relationships and compositional balance. These works are often imbued with a quiet poetry, celebrating the beauty of the everyday. Like the still lifes of Paul Cézanne, whom Gauguin also admired, or even the intimate floral studies of Vincent van Gogh, Ślewiński's still lifes transcend mere representation, becoming meditations on form, color, and the artist's subjective response to the world.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Enduring Legacy

Władysław Ślewiński's work was exhibited in various important venues during his lifetime, contributing to his recognition within artistic circles. He participated in the Salon des Indépendants in Paris, a key exhibition space for avant-garde artists, and also showed his work at the Georges Thomas Gallery. His association with Gauguin and the Pont-Aven school naturally brought him into contact with the leading currents of modern art.

In Poland, his return and subsequent involvement with the Young Poland movement ensured his visibility and influence. His teaching activities further solidified his role in the development of Polish art. Posthumously, his significance has been affirmed through numerous exhibitions. The National Museum in Warsaw, for instance, held a major retrospective of his work in 1983, titled "Władysław Ślewiński 1854-1918," which featured over 300 pieces. The museum has also included his work in thematic exhibitions like "In Search of Form and Synthesis: 20th Century Upper Half."

His paintings are held in major Polish collections, including the National Museums in Warsaw and Krakow, and the Warsaw School of Fine Arts. The Musée de Pont-Aven in France also acknowledges his importance to the artistic history of the region by holding works like Cliffs in Brittany. Private collections, such as that of the Eugenia Ślewińska family, also preserve aspects of his oeuvre.

While perhaps not as internationally famous as his mentor Gauguin, or some of his French Post-Impressionist contemporaries like Van Gogh or Cézanne, Ślewiński's contribution is undeniable. He was a crucial conduit for transmitting modern French artistic ideas, particularly Synthetism, into the Polish art scene. He successfully melded these international influences with his own distinct sensibility and, in his later years, with Polish national themes and landscapes. His art is characterized by its sincerity, its decorative elegance, and its deep, often melancholic, connection to the natural world. He remains a testament to the rich cross-cultural exchanges that defined European modernism and a cherished figure in the history of Polish art.

Władysław Ślewiński passed away in Paris in 1918, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its quiet power and distinctive beauty. His journey from a Polish nobleman to a key associate of Gauguin in Brittany, and finally to an influential figure in the Young Poland movement, reflects a life dedicated to the pursuit of an authentic and modern artistic vision. His legacy lies in his evocative landscapes, his insightful portraits, his harmonious still lifes, and his role in bridging the artistic worlds of Western and Eastern Europe at a pivotal moment in art history.