Adriaen Isenbrant Paintings

Adriaen Isenbrant was a notable figure in the Northern Renaissance, primarily active in Bruges, a hub of artistic innovation in the Low Countries during the 16th century. Born around 1490, Isenbrant's early life is largely undocumented, but he is believed to have originated from the Southern Netherlands. By the time of his documented presence in Bruges in the early 1510s, he had already developed a sophisticated understanding of the artistic trends of the time, likely influenced by the works of Gerard David, among others.

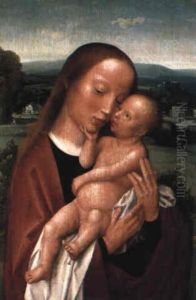

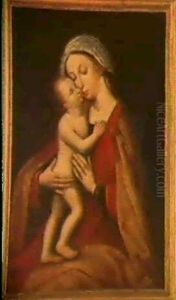

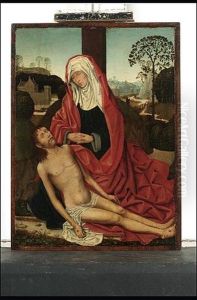

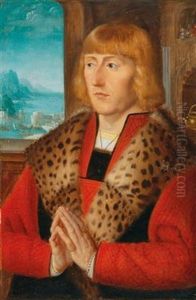

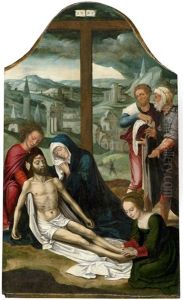

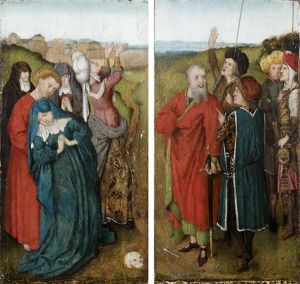

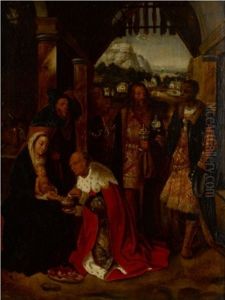

Isenbrant's artistry flourished in an era marked by the transition from the medieval tradition to Renaissance ideals, blending the intricate detail characteristic of Flemish art with the emerging techniques of perspective and humanism. Despite the scarcity of signed or documented works definitively attributed to him, Isenbrant is credited with a significant corpus of paintings, primarily religious in theme. His works are characterized by their delicate treatment of light and shadow, a testament to his mastery of oil painting techniques, and their serene, devotional atmosphere.

Throughout his career, Isenbrant took on various roles within the artists' community in Bruges, including serving as a member of the painters' guild. His influence extended through his workshop, which contributed to the dissemination of his stylistic traits across the region. The precise number of his apprentices and the full scope of his influence, however, remain subjects of scholarly debate, complicated by the common practice of not signing artworks during this period.

Isenbrant's death in 1551 marked the end of an era in Bruges, which was witnessing the gradual shift of artistic prominence to other centers in Europe. Nonetheless, his legacy endured through the continued appreciation of his works, which are today housed in numerous prestigious museums worldwide, offering insight into the rich artistic heritage of the Northern Renaissance. His contributions to the development of religious and secular imagery have cemented his status as an important, though somewhat enigmatic, figure in the history of European art.