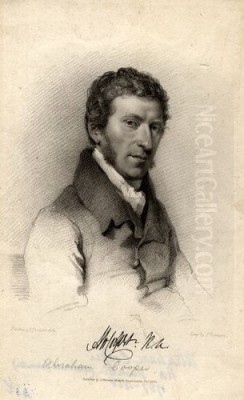

Abraham Cooper RA (1787–1868) stands as a significant figure in the annals of British art, particularly renowned for his dynamic and anatomically precise depictions of animals, primarily horses, and his stirring portrayals of historical battle scenes. Emerging from humble beginnings and largely self-taught, Cooper navigated the competitive London art world to achieve considerable fame and academic recognition, leaving behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its vigour and technical skill. His life and career offer a fascinating glimpse into the world of sporting and military art during a transformative period in British history.

Humble Origins and an Unconventional Path to Art

Abraham Cooper was born in Holloway, London, on September 8, 1787. His family background was modest; his father worked as a tobacconist in Red Lion Street, Holborn. Later, the family moved to Holloway or Hornsey. Unlike many of his contemporaries who benefited from formal artistic training from a young age, Cooper's entry into the world of art was driven by personal passion and necessity rather than privilege. His early life involved practical work rather than academic pursuits.

Around the age of thirteen, Cooper found employment at Astley's Amphitheatre, a popular London venue known for its equestrian performances and theatrical spectacles. This early exposure to horses, their movement, and their dramatic presentation likely played a formative role in shaping his future artistic interests. Working in such an environment would have provided him with invaluable first-hand observation of equine anatomy and behaviour under various conditions.

Following his time at Astley's, Cooper entered the service of Sir Henry Meux, 1st Baronet, a prominent brewer. Initially, Cooper worked as a groom, a position that further deepened his familiarity with horses. It was during this period, around the age of twenty-two (circa 1809), that his artistic inclinations truly surfaced. Possessing a favourite horse owned by Sir Henry, named 'Frolic', Cooper felt a strong desire to capture its likeness. Lacking formal training or materials, he resourcefully acquired rudimentary supplies and began teaching himself the basics of drawing and painting. His initial efforts, reportedly made directly onto a wall, impressed his employer.

Sir Henry Meux, recognizing the young groom's nascent talent, encouraged him to pursue art more seriously. This support was pivotal. It marked the transition for Cooper from a stable hand with an artistic hobby to an aspiring professional painter. His deep, practical understanding of horses, gained through years of close contact, would become the bedrock of his artistic practice, lending an authenticity to his work that resonated with patrons and critics alike.

Mentorship and Early Professional Development

Sir Henry Meux's encouragement extended beyond mere words. He facilitated Cooper's introduction to Benjamin Marshall (1768–1835), who was already an established and highly respected painter of sporting subjects, particularly horses. Marshall, known for his robust and less idealized portrayal of animals compared to some predecessors, became a crucial mentor figure for Cooper. Although Cooper is often described as largely self-taught, the guidance and instruction he received from Marshall were instrumental in refining his technique and understanding the professional art world.

Marshall likely provided Cooper with insights into oil painting techniques, composition, and perhaps most importantly, the business side of being an artist, including securing commissions and exhibiting work. Marshall's own connections within the sporting community would also have been beneficial. Furthermore, Marshall recognized Cooper's potential and encouraged him to submit work to The Sporting Magazine.

The Sporting Magazine, founded in 1792, was a highly popular and influential publication catering to the interests of the British landed gentry and sporting enthusiasts. It featured articles on horse racing, hunting, shooting, and other country pursuits, often accompanied by high-quality engravings based on original paintings. Benjamin Marshall himself was a regular contributor. Having his work accepted and engraved for publication in such a widely circulated journal provided Cooper with invaluable exposure early in his career. It allowed his depictions of horses and sporting scenes to reach a broad and relevant audience, helping to build his reputation beyond his immediate circle. This connection, fostered by Marshall, was a significant stepping stone in Cooper's professional ascent.

Defining an Artistic Style: Animals and Action

Abraham Cooper quickly developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by anatomical accuracy, particularly in his rendering of horses, combined with a flair for dramatic action and narrative. His practical background gave him an intimate knowledge of equine form and movement, which translated into paintings that were both lifelike and dynamic. He excelled at capturing the tension, power, and spirit of his animal subjects, whether they were racehorses at full gallop, hunters clearing fences, or chargers in the heat of battle.

His approach differed somewhat from the refined elegance often seen in the work of earlier masters like George Stubbs (1724–1806), whose paintings often emphasized classical form and scientific observation. While Cooper certainly valued accuracy, his work often possessed a greater sense of immediacy and rugged energy, perhaps influenced by his mentor Benjamin Marshall and the more robust tastes of the Regency and early Victorian eras. He wasn't afraid to depict the strain and exertion of animals in motion or combat.

Cooper's palette was generally strong and his application of paint confident, contributing to the overall vigour of his compositions. He paid close attention to details of tack, attire (in his historical scenes), and setting, grounding his subjects in believable environments. While primarily known for horses, he was also adept at painting other animals, notably dogs, which often featured prominently in his sporting pictures. His ability to integrate figures, both human and animal, into coherent and engaging narrative compositions was a key strength.

His subject matter fell broadly into two main categories: sporting art and historical/battle scenes. The sporting works included portraits of famous racehorses, hunting scenes, and depictions of other country pursuits. The historical paintings often focused on dramatic moments from British history, particularly the English Civil War and the Napoleonic Wars, allowing him to combine his skill in animal painting with an interest in military history and dramatic storytelling.

Major Works and Prestigious Commissions

Throughout his long career, Abraham Cooper produced a significant number of notable paintings, many of which cemented his reputation. One of his earliest successes, and a work often cited as representative of his dramatic flair, is Tam o' Shanter (1814). Based on the famous narrative poem by Robert Burns, this painting vividly depicts the poem's climax, with Tam fleeing on his horse Meg from witches and warlocks, showcasing Cooper's ability to handle narrative, movement, and atmospheric effects.

His interest in military history led to several important battle paintings. The Battle of Ligny (1816) depicted a key engagement from the Napoleonic Wars, fought just two days before Waterloo. His treatments of English Civil War subjects were particularly well-regarded, including The Battle of Marston Moor (exhibited 1819) and The Heroic Conduct of Cromwell at Marston Moor. These works allowed him to display his mastery of complex compositions involving numerous figures, horses in dramatic action, and historical detail. Such paintings appealed to the patriotic sentiments and historical interests of the time.

Beyond these narrative and historical works, Cooper excelled in straightforward animal portraiture, often commissioned by wealthy patrons. A Grey Horse at a Stable Door is a fine example of his ability to capture the individual character and physical presence of an animal in a quieter setting. He received commissions from prominent members of the aristocracy, including the Duke of Grafton, the Duke of Bedford, and the Duke of Marlborough, to paint their prized horses, hunters, and dogs. These commissions were crucial for his financial success and social standing within the art world. He also painted portraits of notable figures associated with the sporting world, such as Mr. Stilwell and his favourite hunter. His work was frequently exhibited at major London venues, including the Royal Academy and the British Institution.

Academic Recognition: Election to the Royal Academy

The Royal Academy of Arts, London, founded in 1768, represented the pinnacle of the British art establishment. Election to its ranks was a mark of significant professional achievement and recognition. Abraham Cooper's growing reputation, built on successful exhibitions and prestigious commissions, led to his consideration by this august body.

In November 1817, Cooper was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was a significant honour, placing him within the Academy's orbit and acknowledging his standing as an artist of note. Associates could exhibit work at the Academy's annual exhibition and were eligible for full membership.

His ascent continued, and just three years later, on November 1, 1820, Abraham Cooper achieved the distinction of being elected a full Royal Academician (RA). This was a testament to the high regard in which his work was held by his peers, who included some of the most famous artists of the day, such as Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830), who was President of the Royal Academy at the time. Full membership conferred greater prestige, voting rights within the Academy, and the right to use the post-nominal letters "RA". For an artist who had started with little formal training, achieving RA status was a remarkable accomplishment, confirming his place among the leading British painters of his generation. He remained an active contributor to the Royal Academy exhibitions for many decades.

Contemporaries, Influence, and Artistic Context

Abraham Cooper worked during a vibrant period in British art history, alongside many talented artists across various genres. His primary sphere was sporting and animal art, a field with a rich tradition in Britain. He followed in the footsteps of masters like George Stubbs and Sawrey Gilpin (1733–1807), but his direct mentor was Benjamin Marshall, whose robust style clearly influenced Cooper's own. Cooper, in turn, played a role in shaping the next generation. His most notable pupils were John Frederick Herring Sr. (1795–1865) and William Barraud (1810–1850). Herring, in particular, became hugely successful and prolific, arguably surpassing his master in popular fame, though Cooper's influence on his early development is undeniable.

Within the broader field of animal painting, Cooper's contemporaries included James Ward (1769–1859), another RA known for his powerful, sometimes Romantic, depictions of animals and landscapes. Henry Thomas Alken (1785–1851) was a prolific producer of sporting prints and paintings, often with a lively, anecdotal quality. A younger, immensely popular figure was Sir Edwin Landseer (1802–1873), whose sentimental and anthropomorphic portrayals of animals, especially dogs, captured the Victorian imagination, representing a different sensibility compared to Cooper's more straightforward or action-oriented approach.

In the realm of historical and battle painting, Cooper's work can be seen in the context of artists like Benjamin West (1738–1820), an American-born painter who became President of the Royal Academy and specialized in large-scale historical subjects, and later, the dramatic historical narratives of artists like Daniel Maclise (1806–1870). While landscape dominated much of the discourse around innovation in British art during this period, with giants like J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851) and John Constable (1776–1837) pushing boundaries, Cooper's focus remained firmly on animal and military subjects, catering to a consistent demand from patrons interested in sport, history, and equine portraiture. His work provided a visual record of these interests, executed with a high degree of technical proficiency that earned him respect even amidst the changing artistic tides represented by figures like Richard Parkes Bonington (1802-1828) or David Wilkie (1785-1841) in genre painting.

Later Life, Privacy, and Enduring Legacy

Abraham Cooper continued to paint and exhibit actively throughout much of his long life. He remained a regular contributor to the Royal Academy exhibitions for nearly six decades, demonstrating remarkable consistency and dedication to his craft. His home for many years was in St John's Wood, a developing area of London popular with artists.

Sources suggest that in his later years, Cooper became increasingly concerned with his privacy. Anecdotal evidence indicates he instructed his family, including his children (he had a son, Alexander, who also became an artist, and possibly others), to safeguard his personal papers and correspondence from public scrutiny. This desire for privacy meant that detailed biographical information and personal insights remained relatively scarce for a long time, with much of his personal archive reportedly not becoming accessible to researchers until the late 20th century. This contrasts with some of his contemporaries whose lives and thoughts are more extensively documented.

Despite this personal reserve, his professional reputation remained strong. His paintings continued to be sought after by collectors who appreciated his skill in capturing the likeness and spirit of horses and the drama of historical events. He died on Christmas Eve, December 24, 1868, at his residence in Woodlands, St John's Wood Road, London (though some sources state Greenwich, perhaps confusing it with his birthplace or a later residence). He was buried in Highgate Cemetery.

Abraham Cooper's legacy endures primarily through his paintings, which are held in numerous public and private collections, including the Tate Britain, the Royal Collection, and various military and sporting museums. His work provides valuable visual documentation of sporting practices, military history, and equine subjects of the 19th century. Furthermore, many of his popular compositions were reproduced as engravings, particularly for publications like The Sporting Magazine and as standalone prints. These reproductions helped to disseminate his imagery widely, ensuring his work reached an audience beyond the galleries and private homes where the originals were displayed. His contribution lies in his mastery of animal anatomy, his ability to convey action and narrative, and his successful career bridging the worlds of sporting art and historical painting within the esteemed framework of the Royal Academy.

Conclusion: An Accomplished Academician

Abraham Cooper's journey from the stables of Sir Henry Meux to the esteemed ranks of the Royal Academy is a testament to his innate talent, dedication, and the opportunities available within the specific cultural milieu of 19th-century Britain. He carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming one of the foremost animal and battle painters of his era. His deep understanding of equine anatomy, honed through practical experience and careful observation, lent an unparalleled authenticity to his depictions of horses in sport and war. While perhaps lacking the revolutionary vision of some landscape contemporaries, Cooper excelled within his chosen genres, producing works characterized by technical skill, dynamic composition, and narrative interest. His paintings remain important examples of British sporting and military art, appreciated for their historical value and their enduring artistic merit, securing his place as a significant figure in the history of British painting.