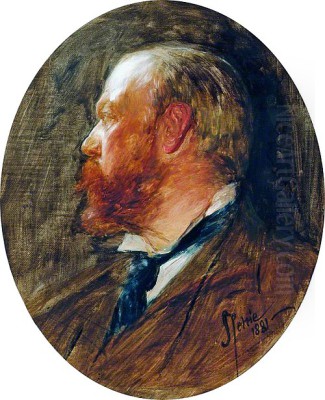

John Pettie (1839-1893) stands as a significant figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art, a painter of Scottish origin who carved a distinguished career primarily in London. Renowned for his vivid historical narratives, dramatic compositions, and masterful use of color, Pettie captured the imagination of the Victorian public. His canvases often throbbed with the tension of bygone eras, particularly the tumultuous 17th century, bringing to life scenes of cavalier gallantry, Puritanical zeal, and the poignant struggles of Scottish history. His journey from the artistic heart of Edinburgh to the prestigious halls of the Royal Academy in London is a testament to his talent, ambition, and the enduring appeal of his theatrical vision.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Edinburgh

Born in Edinburgh on March 17, 1839, John Pettie was the son of Alexander Pettie and Alison Pettie. His early years were spent in East Lothian, but his artistic destiny lay in the Scottish capital. From a young age, he exhibited a clear aptitude for drawing and a fascination with storytelling, qualities that would define his mature work. Recognizing his burgeoning talent, his family supported his decision to pursue art professionally.

At the age of sixteen, around 1855, Pettie enrolled at the Trustees' Academy in Edinburgh, a venerable institution that had nurtured many of Scotland's finest artists. Here, he came under the tutelage of Robert Scott Lauder, a charismatic teacher and accomplished painter who profoundly influenced a generation of Scottish artists. Lauder encouraged his students to explore dramatic historical and literary themes, fostering an environment of creative ambition.

It was at the Trustees' Academy that Pettie formed crucial friendships with a group of exceptionally talented contemporaries who would also achieve significant recognition. This circle included William Quiller Orchardson, with whom he would share a lifelong friendship and professional association, William McTaggart, a future master of Scottish landscape and seascape painting, and other notable figures like Peter Graham and Tom Graham. This group, sometimes informally referred to as "The Clique," shared a common artistic spirit, often drawing inspiration from literature, particularly the historical romances of Sir Walter Scott. Pettie's early work, such as Scene in the Fortunes of Nigel, directly reflects this literary influence. He first exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy in 1858, signaling his formal entry into the professional art world.

The London Calling and Rise to Prominence

The allure of London, then the undisputed center of the British art world, proved irresistible for ambitious young artists. In 1862, John Pettie, along with his close friend William Quiller Orchardson, made the pivotal decision to move south and establish himself in the capital. This move was a bold step, placing him in a highly competitive environment but also offering greater opportunities for patronage and recognition.

Pettie quickly began to make his mark. He started exhibiting at the Royal Academy of Arts, the most prestigious art institution in Britain. His distinctive style, characterized by its dramatic flair, rich coloration, and engaging subject matter, began to attract attention. The Victorian public had a keen appetite for historical paintings that offered both narrative interest and visual spectacle, and Pettie's work catered perfectly to this taste.

His talent did not go unnoticed by the establishment. In 1866, a mere four years after his arrival in London, John Pettie was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was a significant honor, marking him as one of the rising stars of the British art scene. His ascent continued, and in 1873 (some sources state 1874), he was elected a full Royal Academician (RA), cementing his position among the elite of the nation's artists. Membership in the Royal Academy was a hallmark of success, bringing with it prestige, exhibition privileges, and a voice in the direction of British art. He joined the ranks of esteemed Academicians such as Lord Frederic Leighton, Sir John Everett Millais, and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, each contributing to the diverse tapestry of Victorian art.

Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

John Pettie's artistic style is immediately recognizable for its vigor, dramatic intensity, and superb handling of color. He was widely regarded as one of the finest colorists of his generation. His palette could range from rich, jewel-like tones, evoking the sumptuous fabrics of cavalier attire, to more somber, atmospheric hues that conveyed the gravity of a historical moment or the desolation of a battlefield. He possessed an innate understanding of how color could be used to evoke emotion and enhance narrative.

His compositions were often bold and theatrical, carefully staged to maximize dramatic impact. He had a keen eye for the telling gesture, the expressive pose, and the arrangement of figures that could convey a complex story with clarity and force. The influence of the stage is palpable in many of his works, with figures often positioned as if in a dramatic tableau. Pettie was a master of creating suspense and engaging the viewer's imagination, inviting them to piece together the narrative unfolding on the canvas.

Light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, played a crucial role in his work, used not merely for modeling form but for heightening the emotional atmosphere. Deep shadows could conceal and suggest, while strategically placed highlights could draw attention to key elements of the drama. This skillful manipulation of light contributed significantly to the often-brooding and intense mood of his paintings.

Thematically, Pettie was drawn to history, particularly the turbulent periods of the 17th century in Britain, encompassing the English Civil War and the Jacobite rebellions. He depicted cavaliers and Roundheads, scenes of conflict, moments of personal crisis, and the clash of ideologies. Scottish history and its romantic, often tragic, narratives also provided a rich vein of inspiration. Works like The Highland Outpost or scenes depicting figures from Scottish lore resonated with a sense of national identity and historical romance. Beyond grand historical events, Pettie also excelled in genre scenes, often imbued with a similar dramatic or anecdotal quality, such as What d'ye Lack, Madam?, The Prison Pet, and The Tanner. These works showcased his versatility and his ability to find compelling human stories in diverse settings. His approach often carried a strong Romantic sensibility, emphasizing emotion, individualism, and the picturesque qualities of the past.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Throughout his career, John Pettie produced a remarkable body of work, with several paintings standing out as particularly representative of his talent and thematic preoccupations. These works cemented his reputation and continue to be admired for their technical brilliance and narrative power.

The Duke of Monmouth's Interview with James II (1880s, specific date varies) is a prime example of Pettie's ability to capture a moment of intense historical drama. The painting depicts the captured Duke of Monmouth, illegitimate son of Charles II, pleading for his life before his uncle, King James II, after the failed Monmouth Rebellion. Pettie masterfully conveys the tension and desperation of the scene, the contrasting emotions of the supplicant Duke and the implacable King. The rich, dark palette and the focused lighting enhance the somber mood and the gravity of the encounter.

Disbandment (often referred to as The Disbanded or The Disbanded Regiment) is another powerful work, likely depicting a scene from the aftermath of a conflict, perhaps the Jacobite risings. It typically shows a solitary, dejected Highland soldier, his cause lost, his future uncertain. The painting evokes a profound sense of pathos and resignation, a common theme in Pettie's work that explored the human cost of war and political upheaval. The expressive pose of the figure and the atmospheric landscape contribute to the painting's emotional impact.

Cromwell's Saints (also known as The Sainted Cromwell or similar variations) delves into the era of the English Civil War, a period Pettie frequently revisited. These works often explored the character of Oliver Cromwell and his Puritan followers. Pettie's portrayals were nuanced, avoiding simple caricature and instead seeking to capture the complex motivations and intense convictions of these historical figures. His ability to convey character through facial expression and posture was a hallmark of his historical portraits.

The Drumhead Court-Martial (exhibited 1865) is an early but significant work that showcases Pettie's talent for dramatic staging. The scene depicts a summary military trial, likely in the field, with the accused figure at the center of a tense group of officers. The starkness of the situation and the grim expressions of the participants create a powerful sense of impending judgment. This work helped to establish Pettie's reputation as a painter of compelling historical narratives.

Other notable paintings include Two Strings to Her Bow (1887), a charming and popular genre scene displaying a lighter touch, and The Vigil (1884), which depicts a young knight keeping watch over his armor before his investiture, a theme rich in chivalric romance. Works like Three Assassins, A Highland Outpost, and The Chieftain's Candlesticks further illustrate his fascination with dramatic encounters and Scottish themes. Each of these paintings, whether grand historical statements or more intimate genre pieces, bears the unmistakable imprint of Pettie's dramatic vision and his skill as a colorist and storyteller.

A Circle of Influence: Contemporaries and Collaborators

John Pettie's artistic journey was shaped not only by his individual talent but also by his interactions with a vibrant community of fellow artists. His closest and most enduring artistic relationship was with William Quiller Orchardson. Their friendship, forged in their student days at the Trustees' Academy under Robert Scott Lauder, continued throughout their careers. They shared a studio for a time after moving to London and provided mutual support and encouragement. While their styles evolved distinctively—Orchardson becoming known for his elegant, psychologically astute society dramas and historical scenes—their shared grounding in Lauder's teachings and their early ambitions created a lasting bond.

His connection with William McTaggart, another prominent member of the "Edinburgh School," remained, though McTaggart's path led him to become one of Scotland's foremost interpreters of its coastal landscapes and seas, a different thematic direction from Pettie's historical narratives. Nevertheless, the shared formative experiences in Edinburgh provided a common artistic heritage.

Within the broader Victorian art scene, Pettie occupied a distinct niche. While the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, with figures like John Everett Millais (in his early phase), William Holman Hunt, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, had earlier challenged academic conventions with their detailed realism and literary symbolism, Pettie's work aligned more with the Victorian taste for historical romance and dramatic narrative painting. He was a contemporary of artists like Lord Frederic Leighton and Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, who excelled in classical and historical subjects, though Pettie's style was generally more robust and less polished than theirs.

His dramatic historical scenes found parallels in the work of artists like Frank Dicksee, who also painted romantic and chivalric subjects. Pettie's focus on character and human drama can be seen as part of a wider Victorian interest in historical personalities, an interest also explored by portraitists and sculptors of the era, such as George Frederic Watts. Unlike the social realist painters such as Luke Fildes or Hubert von Herkomer, who often depicted contemporary social issues, Pettie's gaze was firmly fixed on the past, finding in its conflicts and characters a rich source for his art. Even animal painters like Sir Edwin Landseer or Briton Rivière, who often imbued their subjects with narrative or allegorical meaning, shared the Victorian penchant for storytelling that Pettie so masterfully exploited in his historical canvases.

The Man Behind the Easel: Personal Pursuits and Character

Beyond his public persona as a successful Royal Academician, John Pettie led a rich personal life, marked by a deep love for music and strong family connections. He was a keen amateur musician himself and his home, particularly his studio, became a welcoming place for musical gatherings. He actively supported and promoted younger musicians, most notably the Scottish composer Hamish MacCunn. Pettie organized concerts to showcase MacCunn's work, playing a significant role in launching the young composer's career.

This connection with MacCunn became even more personal when Pettie's daughter, Alison, married Hamish MacCunn in 1888. This union brought the composer firmly into the Pettie family circle. It is noted that Pettie's wife (whose first name may also have been Alison, though sources can be slightly ambiguous, distinguishing her from his daughter Alison) often served as a model for figures in his paintings, a common practice for artists of the period. The family environment appears to have been one of artistic and cultural vibrancy.

In addition to his ambitious exhibition pieces, Pettie also undertook illustration work, contributing to popular periodicals of the day such as The Quiver and Good Words for the Young. This work, while perhaps less prestigious than his Royal Academy submissions, provided a steady income and allowed his art to reach a wider audience. It also demonstrated his versatility and his ability to adapt his narrative skills to the demands of textual illustration.

Accounts of Pettie's character suggest he was somewhat introverted and shy in public. This personal reserve sometimes made public expression, particularly in formal settings or, as one source notes, in certain religious activities, a challenge for him. Despite this, he held strong personal convictions and was known to be active in supporting his local church and charitable causes, demonstrating a commitment to his community. His art, with its bold drama and expressive figures, perhaps served as a powerful outlet for a man who might have been less outwardly demonstrative in person.

The Final Chapter and Enduring Legacy

John Pettie remained a productive and respected artist throughout his career. He continued to exhibit regularly at the Royal Academy and other institutions, and his works were sought after by collectors who appreciated his distinctive blend of historical subject matter, dramatic intensity, and rich coloring. His paintings were widely reproduced as engravings, further popularizing his images and making them accessible to a broader public beyond the exhibition halls.

His dedication to his craft was unwavering. Even in his later years, he maintained a high standard of execution and continued to explore the historical themes that had captivated him from his youth. His body of work represents a significant contribution to the genre of historical painting in Britain during the Victorian era.

John Pettie passed away on February 21, 1893, in Hastings, at the relatively young age of 53 (though one provided source snippet erroneously gives a much later death date of 1923, the 1893 date is historically established). His death was mourned by the art community and the public who had admired his work for decades. He left behind a legacy as a master storyteller in paint, an artist who could transport viewers to other times and immerse them in the human dramas of the past.

Today, John Pettie's paintings are held in numerous public collections in the United Kingdom and beyond, including the Tate Britain, the National Galleries of Scotland, and various regional museums. His work continues to be studied for its technical skill, its engagement with historical narrative, and its reflection of Victorian cultural tastes. While art historical fashions have shifted over time, the power of Pettie's dramatic compositions and his skill as a colorist ensure his enduring place in the annals of British art. He remains a key figure for understanding the popularity and evolution of historical painting in the 19th century.

Conclusion

John Pettie RA was a quintessential Victorian artist in many respects, yet he possessed a unique vision that set him apart. Born and trained in Scotland, he rose to prominence in the competitive London art world, achieving the highest accolades of the Royal Academy. His canvases, alive with the clash of swords, the tension of clandestine meetings, and the pathos of defeated heroes, spoke to a public fascinated by history and romance. As a superb colorist and a natural dramatist, he imbued his historical scenes with an emotional resonance that transcended mere illustration. From the corridors of power in The Duke of Monmouth's Interview with James II to the solitary despair of The Disbanded, Pettie captured the human element within the grand sweep of history. His friendships with contemporaries like Orchardson, his passion for music, and his dedication to his craft paint a picture of a committed and multifaceted artist. John Pettie's legacy is that of a painter who not only chronicled the past but brought it vividly, and often poignantly, to life.