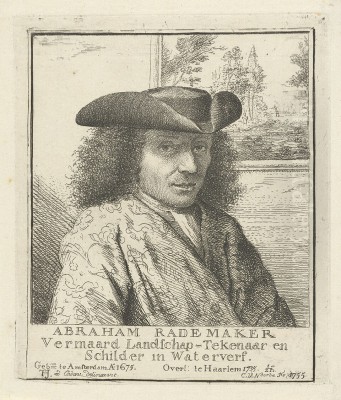

Abraham Rademaker (1675/1676 – 1735) stands as a significant figure in early 18th-century Dutch art, a period that saw a continuation and evolution of the rich artistic traditions established during the Dutch Golden Age. As a prolific painter, etcher, printer, and art dealer, Rademaker carved a unique niche for himself, primarily through his meticulous and evocative depictions of Dutch towns, cities, castles, and rural landscapes. His work not only captured the aesthetic charm of his homeland but also served as an invaluable historical record, preserving the appearance of numerous sites for posterity.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Lisse, a town in the province of South Holland, between 1675 and 1676, Abraham Rademaker was the son of Frederik Rademaker, a glassmaker. This familial connection to a craft, albeit different from painting or printmaking, might have instilled in young Abraham an appreciation for skilled workmanship and visual representation. From an early age, he reportedly exhibited a profound interest in drawing and painting.

Remarkably, Rademaker is largely considered a self-taught artist. In an era when formal apprenticeships under established masters were the conventional route to an artistic career, Rademaker's ability to master the intricate skills of drawing, painting, and particularly etching, speaks volumes about his dedication, natural talent, and keen observational abilities. He would have likely studied the works of other artists, both contemporary and from the preceding Golden Age, absorbing techniques and stylistic nuances through careful examination and practice. The challenges for a self-taught artist in this period would have been considerable, including access to materials, technical knowledge (especially for complex processes like etching), and entry into the established art market and guilds.

Relocation to Amsterdam and Professional Flourishing

In 1706, a significant year in his personal and professional life, Abraham Rademaker married Maria Roosekrans. Following his marriage, he relocated to Amsterdam, the vibrant commercial and cultural heart of the Netherlands. This move was pivotal, as Amsterdam offered a larger market for artists, a thriving publishing industry, and a greater concentration of patrons and fellow creatives.

In Amsterdam, Rademaker established himself not only as an artist but also as a printmaker and dealer. He ran his own printing business, which allowed him to produce and disseminate his own works, as well as potentially those of other artists. This entrepreneurial aspect of his career was common among Dutch artists who sought to control the production and sale of their prints, a lucrative segment of the art market. His business acumen, coupled with his artistic skill, enabled him to build a successful career.

Artistic Style and Thematic Focus

Rademaker's artistic output was diverse, encompassing oil paintings, watercolors, and, most notably, a vast number of etchings. His primary subjects were the landscapes, cityscapes, and architectural heritage of the Netherlands. He possessed a keen eye for detail, rendering buildings with architectural accuracy and capturing the specific character of various locales.

His landscapes often evoke a sense of tranquility and picturesque charm, characteristic of much Dutch landscape art. While the dramatic intensity of masters like Jacob van Ruisdael from the previous century might not be his primary mode, Rademaker's work conveys a deep affection for the Dutch environment. He depicted not just grand vistas but also more intimate scenes of rural life, canals, and the distinctive flat terrain of the Netherlands.

In his architectural drawings and prints, Rademaker demonstrated a meticulous approach. He documented castles, country estates, city gates, churches, and public buildings. These were not merely dry, topographical renderings; he often imbued them with an atmospheric quality, using light and shadow effectively to create depth and visual interest. There's a certain romantic sensibility in his depiction of ancient ruins or venerable structures, hinting at the passage of time and the enduring presence of history in the landscape. This can be seen as a precursor to the more pronounced Romantic movement that would flourish later in the 18th and 19th centuries.

His technique in etching was particularly refined. He utilized fine lines and careful cross-hatching to achieve a range of tones and textures, essential for conveying the materials of buildings and the nuances of foliage and sky. His compositions were generally well-balanced, guiding the viewer's eye through the scene in a clear and engaging manner.

The Magnum Opus: Kabinet van Nederlandsche Outheden en Gezichten

Abraham Rademaker's most significant and enduring achievement is undoubtedly his monumental publication, Kabinet van Nederlandsche Outheden en Gezichten (Cabinet of Dutch Antiquities and Views), also known by slight variations in title such as Kabinet van Nederlandsche landsteder en ophem van Nederlandsche steden. Published around 1725-1732, this ambitious work comprised approximately 300 etchings.

This extensive collection systematically documented a wide array of Dutch towns, cities, castles, ruins, and important historical sites across the Northern Netherlands, the Rhine region, and Cleves (Kléve). The Kabinet was a remarkable undertaking, reflecting a growing interest in national heritage and topography. Each print was typically accompanied by a brief descriptive text, further enhancing its documentary value.

The subjects ranged from well-known urban centers to more obscure rural locations. He depicted fortifications, stately homes, ancient church towers, and picturesque village scenes. The Vecht river region, known for its elegant country estates, was a recurring subject, with Rademaker capturing the grandeur and charm of these elite residences. The Kabinet served multiple purposes: it was a source of pride in Dutch heritage, a visual travelogue for those who could not visit these places, and a valuable reference for historians and antiquarians. The sheer scale and comprehensiveness of this project underscore Rademaker's diligence and his commitment to preserving the visual record of his country. Artists like Roelant Roghman had earlier produced series of castle drawings, and Rademaker's Kabinet can be seen as a grand culmination of this topographical tradition in print.

Other Notable Works and Artistic Endeavors

Beyond the Kabinet, Rademaker produced numerous individual prints and paintings. Among his specific works mentioned are:

Oude Kerk at Warmont: An etching showcasing an old church, likely included in or similar in style to the prints in his Kabinet. Such works highlight his ability to capture the character of venerable religious architecture.

View of the Overtoom: A panoramic print, created in collaboration with the printmaker and publisher Leonard Schenk. It depicted the Overtoom, a vital waterway and portage point at the entrance to Amsterdam, bustling with activity and lined with buildings. This collaboration with Schenk, a prominent figure in Amsterdam's print trade, indicates Rademaker's integration into the city's artistic network.

Gynwens appartenant a Mr. Christian Wencel: This etching, depicting a figure in an idealized landscape with a grand building, suggests Rademaker also undertook commissions or created works with a more allegorical or personalized character, possibly for specific patrons.

View of the Singel Canal: Another collaborative work with Leonard Schenk, this print would have captured one of Amsterdam's iconic canals, showcasing the city's unique urban fabric. The cityscapes of artists like Jan van der Heyden and Gerrit Berckheyde from the Golden Age had set a high standard for such views, and Rademaker continued this tradition.

Spaanwoudermolen: An etching of a windmill in Haarlem, demonstrating his interest in these characteristic Dutch structures, which were not only picturesque but also vital to the country's economy and land reclamation.

De Catoen drukkerij met het Torentje: A print depicting a cotton printing factory in Amsterdam, offering a glimpse into the city's commercial and industrial life.

Capelle aan den Leek: A depiction of a chapel, likely in a rural or semi-rural setting, showcasing his attention to smaller, perhaps less monumental, architectural subjects.

Italianate Landscapes: The mention of two Italianate landscape paintings, executed in watercolor and ink, suggests that Rademaker, like many Dutch artists (such as Isaac de Moucheron or earlier figures like Jan Both and Nicolaes Berchem), was also drawn to the allure of Italian scenery, even if his primary focus remained on Dutch subjects. This could have been through studying prints by other artists or perhaps even from a journey, though the latter is not definitively documented.

View of Amsterdam's Jewish Quarter: This print, based on an original work by Pieter Stevens van Gunst, another contemporary artist and engraver, further illustrates the interconnectedness of the printmaking world, where images were often copied, adapted, and reissued.

Rademaker also reportedly painted a depiction of a Jesuit church. While the accuracy of this particular representation has been questioned by some sources, it indicates his willingness to tackle diverse architectural subjects, including those with religious significance.

Collaborations, Influences, and Contemporaries

The art world of 18th-century Amsterdam was a relatively close-knit community, and Rademaker engaged with several contemporaries. His collaborations with Leonard Schenk (c. 1696–1767), a member of a prominent family of map and print publishers, were significant, likely facilitating wider distribution of his images. The fact that Rademaker based a print on a work by Pieter Stevens van Gunst (1658/9–1731) is also noteworthy.

Rademaker himself took on students. Cornelis Pronk (1691–1759), who became a renowned topographical artist in his own right, is documented as having studied perspective with Rademaker. This indicates Rademaker's mastery of this crucial artistic skill and his role in transmitting knowledge to the next generation. Pronk, along with artists like Jan de Beijer (1703-c.1780) and Paulus van Liender (1731-1797), would continue the tradition of topographical drawing and printmaking throughout the 18th century.

In terms of influences, while Rademaker was self-taught, he would have been immersed in the visual culture of his time. The towering legacy of Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), particularly his etchings of landscapes and his masterful use of chiaroscuro, would have been inescapable. The detailed architectural renderings of artists like Pieter Saenredam (1597–1665), who specialized in church interiors, or the cityscapes of Jan van der Heyden (1637–1712) and Gerrit Berckheyde (1638–1698), provided a rich heritage of architectural depiction. The topographical drawings of castles and estates by Roelant Roghman (1627–1692) also prefigured Rademaker's interest in such subjects. The prolific printmaker Romeyn de Hooghe (1645-1708) also created extensive series of topographical and historical prints, setting a precedent for ambitious publishing projects like Rademaker's Kabinet.

The St. Luke's Guild and Later Years

Despite being a "secular person" (likely meaning not primarily focused on religious art commissions in the way some earlier artists were, or perhaps indicating he was not initially a guild member due to his diverse activities as a dealer and publisher), Abraham Rademaker joined the Guild of Saint Luke in 1732. The Guild of St. Luke was the traditional organization for painters and other artists in many Dutch cities. Membership conferred professional status and often regulated the practice of art within a city. His relatively late entry might reflect his established independence or the evolving nature of the art market, where publishing and dealing provided alternative avenues for success.

Abraham Rademaker passed away in Haarlem in 1735, at the age of approximately 60. His death marked the end of a productive and influential career. The auction of his estate reportedly fetched over 8,000 Dutch guilders, a considerable sum at the time, attesting to the value of his collection and original works and indicating his financial success.

Legacy and Artistic Impact

Abraham Rademaker's legacy is multifaceted. Firstly, his works, especially the Kabinet van Nederlandsche Outheden en Gezichten, constitute an invaluable historical archive. Many of the buildings and sites he depicted have since been altered or no longer exist. His prints provide crucial visual evidence for historians, architectural historians, and archaeologists studying the Netherlands of the early 18th century.

Secondly, his art contributed to the genre of topographical depiction. While not always strictly adhering to precise reality (artists of the period often took minor liberties for compositional or aesthetic reasons), his commitment to capturing the essence and key features of specific locations was paramount. This had an impact on subsequent map-making and topographical art. His detailed views provided a visual understanding of the country that complemented cartographic efforts.

Thirdly, his prints were popular among collectors both in his lifetime and subsequently. The accessibility of prints, compared to unique paintings, allowed a broader audience to acquire and appreciate art. Rademaker catered to this market effectively, producing works that were both informative and aesthetically pleasing. His prints continue to be collected and are found in major museum collections worldwide, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the British Museum in London.

His influence can also be seen in the work of his students, like Cornelis Pronk, who further developed the tradition of topographical art. Rademaker's success as a self-taught artist and entrepreneur also serves as an interesting case study in the Dutch art world of his time. He demonstrated that talent, combined with diligence and business sense, could lead to a prominent career.

While the 18th century in Dutch art is sometimes overshadowed by the brilliance of the 17th-century Golden Age, artists like Abraham Rademaker played a crucial role in continuing and adapting these traditions. He was not an avant-garde innovator in the modern sense, but his dedication to documenting the Dutch landscape and its architectural heritage, executed with considerable skill and artistic sensitivity, has ensured his lasting importance. His work reflects a deep connection to his homeland and a desire to preserve its visual identity for future generations. Figures like Cornelis Troost (1696-1750), known for his genre scenes and portraits, or the celebrated flower painter Jan van Huysum (1682-1749), were his contemporaries, each contributing to the diverse artistic tapestry of the 18th-century Netherlands, a period that deserves recognition for its own distinct achievements. Rademaker's contribution lies firmly in his meticulous and loving portrayal of the Dutch world around him.