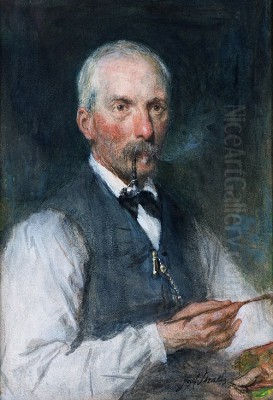

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch stands as one of the most significant figures of the Hague School, a pivotal movement in 19th-century Dutch art. Born in The Hague on June 19, 1824, and passing away in the same city on March 24, 1903, Weissenbruch dedicated his life to capturing the unique atmosphere and luminous quality of the Dutch landscape. Primarily celebrated as a painter, especially for his masterful watercolors, he was also a skilled etcher, printmaker, and draughtsman, leaving behind a rich and varied body of work that continues to captivate viewers today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Weissenbruch's journey into art began in an environment steeped in creativity. He hailed from an artistic family; his father, Johannes Weissenbruch, though a chef and restaurateur by trade, was an avid art collector and amateur painter. His mother also possessed a keen interest in the arts, fostering a home atmosphere where artistic pursuits were encouraged. Several relatives, including uncles and brothers, were also artists, providing young Jan Hendrik with early exposure and likely informal instruction. This familial background undoubtedly nurtured his innate talent and inclination towards visual expression.

His formal training commenced at the Hague Academy of Art, where he honed his technical skills. During these formative years, Weissenbruch absorbed the prevailing artistic currents, initially leaning towards the Romantic tradition. He received guidance from established artists, notably Andreas Schelfhout, a prominent Romantic landscape painter known for his meticulous detail and picturesque compositions, particularly his rendering of skies and clouds. Weissenbruch also looked further back, deeply admiring the 17th-century Dutch Masters, with Jacob van Ruisdael being a particularly strong influence, especially in the depiction of dramatic cloudscapes and expansive landscapes.

The Rise of the Hague School

The mid-19th century witnessed a significant shift in Dutch art. Artists began moving away from the idealized visions of Romanticism towards a more direct, realistic engagement with their surroundings. This movement, which became known as the Hague School, drew inspiration from the French Barbizon School painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny, who advocated for painting outdoors (en plein air) and capturing the unadorned beauty of rural life and landscapes.

The Hague School artists shared this commitment to realism but focused intently on the specific characteristics of the Dutch environment. They were particularly fascinated by the interplay of light and atmosphere, often working with a palette characterized by subtle greys, browns, and greens, earning them the moniker "Grey School." Their goal was not photographic accuracy but rather to convey the mood and feeling of the landscape – the damp air, the overcast skies, the shimmering reflections in canals and waterways. They sought the poetry in the everyday Dutch scene.

Weissenbruch's Place in the Movement

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch emerged as a central and highly respected figure within the Hague School. He was not merely a participant but a driving force, embodying the movement's core principles. His deep understanding of the Dutch landscape and his exceptional ability to render its atmospheric qualities made him a leader among his peers. He worked alongside other luminaries of the school, including the poignant genre painter Jozef Israëls, the influential landscape painter Willem Roelofs, the Maris brothers (Jacob, Matthijs, and Willem), known for their distinct approaches to landscape and figure painting, Anton Mauve, famous for his pastoral scenes, the sensitive landscape artist Gerard Bilders, and the church interior specialist Johannes Bosboom.

Together with Willem Roelofs and his cousin, the cityscape painter Jan Weissenbruch, Jan Hendrik played a crucial role in founding the Pulchri Studio in The Hague in 1847. This artists' society provided a vital platform for exhibitions, discussions, and mutual support, becoming the institutional heart of the Hague School. It marked a significant step in organizing the artists and presenting their shared vision to the public, solidifying the movement's identity and influence. Weissenbruch's involvement underscored his commitment to fostering a collaborative artistic community.

Mastering Light and Atmosphere

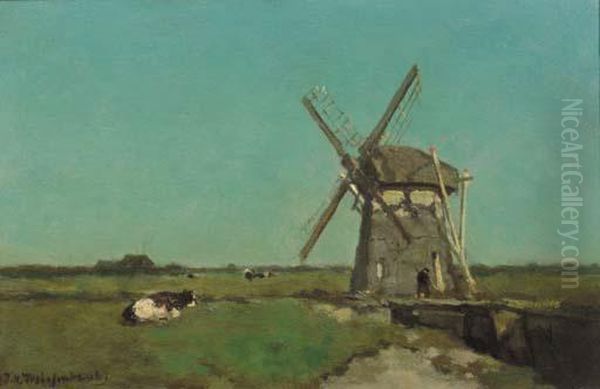

The defining characteristic of Weissenbruch's art is his extraordinary sensitivity to light and atmosphere. He possessed an almost uncanny ability to capture the subtle nuances of the Dutch sky – the towering cloud formations, the soft, diffused light filtering through moisture-laden air, the dramatic contrasts between sun and shadow. His contemporaries often remarked on his obsession with the sky, recognizing it as the key element in his compositions. He believed that the sky dictated the overall mood and light of the landscape beneath it.

His mastery extended across mediums. In his oil paintings, he used fluid brushwork and carefully modulated tones to create a sense of depth and luminosity. However, he achieved perhaps his greatest renown as a watercolorist. In watercolor, his technique was broad, transparent, and seemingly effortless, allowing him to capture the fleeting effects of light and weather with remarkable immediacy and freshness. His watercolors are celebrated for their brilliance and atmospheric depth, showcasing his profound understanding of the medium's potential. This focus on light and realistic depiction led some to compare his clarity and precision to the 17th-century master Johannes Vermeer, calling Weissenbruch a "Vermeer of the nineteenth century."

Evolution of Style

Weissenbruch's artistic style was not static; it evolved throughout his long career. His early works, influenced by Schelfhout and the Romantic tradition, often display a higher degree of detail and a more conventional compositional structure. While already showing a keen interest in atmospheric effects, these earlier pieces adhere more closely to established landscape conventions.

As he matured and became more deeply involved with the Hague School's principles, his style became broader and more suggestive. He began to simplify forms, focusing less on minute detail and more on capturing the overall impression and mood of a scene. His brushwork became looser and more expressive. This later style emphasized the synthesis of light, air, and landscape, aiming to convey the inherent power and poetry of nature through suggestion rather than explicit description. He learned to eliminate non-essential details to strengthen the impact of light and space.

Technique and Process

Understanding Weissenbruch's working methods provides insight into his artistic achievements. He was a firm believer in direct observation and spent considerable time sketching outdoors, directly confronting the landscape he wished to depict. He would often make rapid studies in pencil, charcoal, or watercolor to capture fleeting effects of light and weather. These plein air studies served as vital source material.

However, he typically completed his major oil paintings and finished watercolors in the studio. Here, he could carefully compose the picture, drawing upon his outdoor sketches and his deep memory of the landscape's feel. He might use preliminary studies in charcoal or crayon to work out the tonal structure before committing to paint. This combination of direct outdoor observation and considered studio execution allowed him to balance spontaneity with thoughtful composition, resulting in works that feel both immediate and enduringly structured.

Iconic Dutch Landscapes

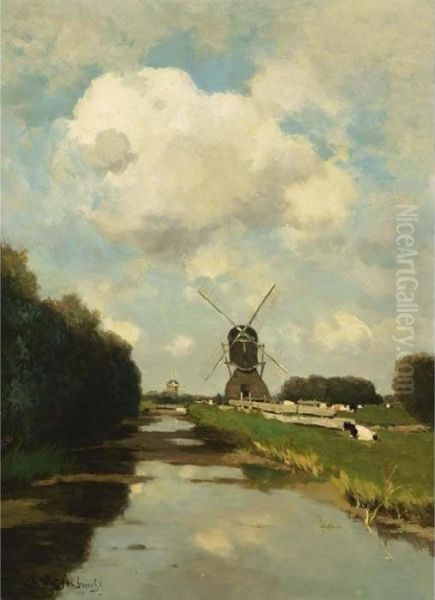

Weissenbruch's subject matter remained consistently focused on the landscapes and waterways of his native Netherlands. He painted the flat polder lands stretching towards the horizon, often punctuated by windmills. Canals and rivers feature prominently, their surfaces reflecting the ever-changing skies. He depicted tranquil beaches under vast cloudscapes and intimate views of rural villages and farmsteads.

While predominantly a landscape painter, he also turned his attention to cityscapes, particularly views of The Hague and other historic towns. He traveled within the Netherlands, finding inspiration in locations like Noorden and Culemborg, known for their picturesque river views. A trip to Barbizon, the heartland of the French school that influenced his own, resulted in works like Forest Landscape (c. 1900), showing his engagement with different types of scenery while retaining his characteristic focus on light. His work is a visual celebration of the Dutch environment in all its varied, often subtle, beauty.

A Touch of Romanticism Preserved

Despite his commitment to the realism championed by the Hague School, a subtle strain of Romanticism persisted in Weissenbruch's work, particularly in his choice of certain subjects. He showed a fondness for depicting elements of Holland's architectural past, such as old city gates, fortifications, and drawbridges – structures that were often disappearing due to modernization during his lifetime.

Paintings featuring these elements, like Steigerpoort, carry an undercurrent of nostalgia, a quiet lament for a vanishing world. This interest in historical architecture adds another layer to his work, blending his keen observation of the present with a sensitivity to the passage of time and the beauty found in remnants of the past. It demonstrates that his realism was infused with personal feeling and a connection to his country's heritage.

Spotlight on Key Works

Several works stand out as representative of Weissenbruch's oeuvre:

Back-garden at the Kazernestraat, The Hague (c. 1890): This painting offers an intimate urban scene, focusing on the blossoming trees and light effects within a walled city garden. It showcases his ability to find beauty in everyday settings and his skill in rendering light filtering through foliage.

Autumn Landscape (1875): Housed in the Rijksmuseum, this work captures the damp, hazy atmosphere of the Zeeland region in autumn. The muted colors and soft focus exemplify the Hague School's "grey" palette and emphasis on mood over precise detail.

Harbor View: Directly referencing the compositional strategies of Jacob van Ruisdael, this work demonstrates Weissenbruch's ongoing dialogue with the Dutch Golden Age masters. It focuses on the dynamic relationship between sky, water, and shoreline in a bustling harbor scene.

Noorden Landscape: Depicting the village of Noorden along the Nieuwkoopse Plassen (lakes), this painting is a quintessential Weissenbruch scene – expansive water, low horizon, and a dominant, luminous sky filled with clouds, capturing the essence of the Dutch wetlands.

Steigerpoort: This work, depicting an old town gate, is notable not only for its subject matter, linking to Weissenbruch's interest in historical architecture, but also for its provenance, having entered the British Royal Collection, indicating his international recognition during his lifetime.

These examples illustrate the range of his subjects and the consistent brilliance of his handling of light and atmosphere, whether in intimate garden scenes, broad polder landscapes, or views marked by historical resonance.

Influences Revisited

Weissenbruch's artistic identity was shaped by a confluence of influences. The early impact of Andreas Schelfhout provided him with a solid foundation in Romantic landscape techniques. However, the enduring inspiration throughout his career came from the 17th-century Dutch Masters, particularly Jacob van Ruisdael, whose dramatic skies and atmospheric depth resonated deeply with Weissenbruch's own sensibilities.

The principles of the French Barbizon School, emphasizing realism and outdoor painting, were also crucial, filtered through the collective ethos of the Hague School. Artists like Constant Troyon and Jules Dupré, alongside Corot and Daubigny, contributed to the broader European shift towards landscape realism that nurtured the Dutch movement. Weissenbruch synthesized these influences into a style that was distinctly his own, yet firmly rooted in both Dutch tradition and contemporary European trends.

Legacy and Recognition

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch enjoyed considerable recognition during his lifetime. He began exhibiting regularly in 1847 and participated in numerous national and international exhibitions, winning awards and gaining patrons both in the Netherlands and abroad, as evidenced by his work entering the British Royal Collection. He was regarded as one of the pillars of the Hague School, admired by fellow artists and collectors alike.

His legacy extends beyond his own impressive body of work. As a leading figure in the Hague School and a co-founder of the Pulchri Studio, he helped shape the course of Dutch art in the latter half of the 19th century. His dedication to capturing the specific light and atmosphere of the Netherlands influenced subsequent generations of Dutch painters. Furthermore, his work found admirers internationally; the French Impressionist Pierre-Auguste Renoir is noted to have been inspired by Weissenbruch's paintings, highlighting his reach beyond national borders. Today, his works are held in major museums, including the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam and the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, ensuring his continued appreciation.

Conclusion

Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch remains a towering figure in Dutch art history. His profound connection to the landscape of the Netherlands, combined with his exceptional technical skill and unparalleled sensitivity to light and atmosphere, resulted in a body of work that is both deeply national and universally appealing. As a key member of the Hague School, he bridged the gap between the Dutch Golden Age masters he revered and the modern sensibilities of his own time. His paintings and watercolors, particularly his luminous depictions of Dutch skies and waterways, continue to resonate with viewers, offering timeless visions of beauty found in the interplay of nature, light, and air. He was, and remains, a true master of Dutch light.